On October 4th, 1994, at an artist panel discussion for MoMA’s Cy Twombly retrospective, Richard Serra made an offhand comment about how “The last century of art has been based on a misreading of Cezanne.”

To a young, impressionable student/fanboi still putting his contemporary art world view together, this was a shock. Because it was Serra, and because I still assumed there was some right art historical “answer” to be gotten to, and because Serra didn’t bother to say how everybody got it wrong, it lodged in my brain for years.

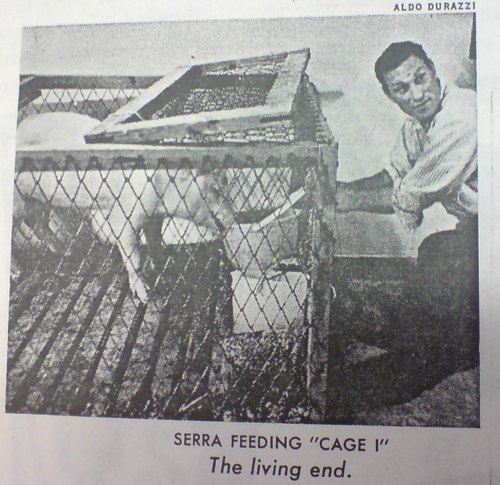

And so it was that at some point a couple of years later, when I met him at a party, I asked him what he’d meant. Of course, he didn’t remember what he’d said, or the context, so he gamely tried to float a couple of possible theories, but nothing that matched the seeming conviction with which I’d remembered him saying it. So I tried to forget about it.

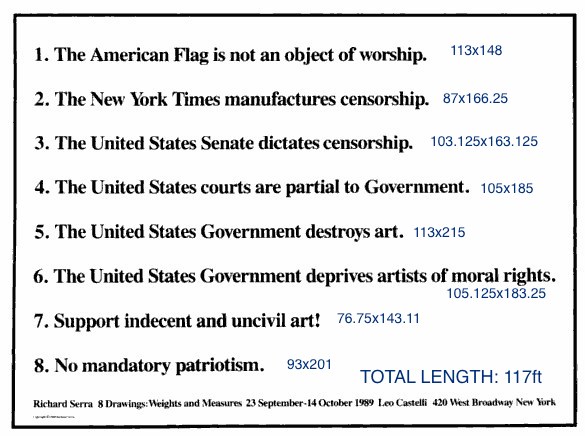

And I thought I had, at least until just now, when I was reading Serra’s discussion with Gary Garrels in the Richard Serra: Drawing catalogue. They were talking about the “jump” in Serra’s work after 1989 in terms of Cezanne:

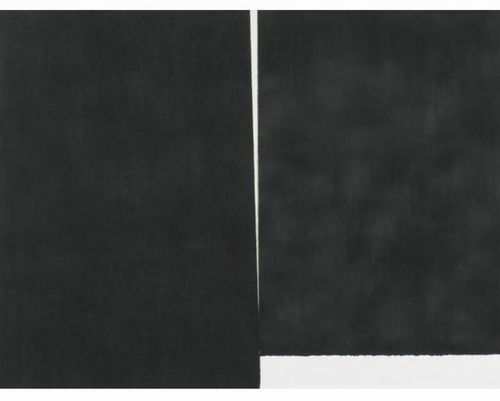

GG: Those double-panel drawings, rather than dealing with a wall or with a room or a space, deal with internal relationships.

RS: They are masses in relation to one another. They’re not about composition or figure-ground; they emphasize the comparison of different weights in juxtaposition.

GG: So this, to me, is again another jump.

RS: For me they have more to do with Cezanne than with Malevich. I wasn’t looking at Cezanne when I conceived them, but in retrospect, I see a clear connection in the way they deal with weight and mass in relation to shape. They’re the opposite of the floating shapes of Constructivism and Malevich, referred to in drawings like Heir

The comparison of the diptychs with Cezanne may be a stretch, but no one else comes to mind who deals so physically with mass and weight. No one talks about the weight of Cezanne, but there’s a manifestation of weight there that’s not in Picasso, not in Matisse, barely in anyone who follows. Cezanne is obviously interested in gravity and in the relation of weight to plane. Take Still Life with Plaster Cupid [ca. 1894], in the Courtauld, where he punches a hole in the space, and you think the apples and onions are going to roll off the table. The only thing holding them in place is their weight. They have the weight of cannonballs.

So the answer, then, is C) gravity.

But then, literally, as I’m typing this in from the book, it’s 41:00 into the recording of the panel, right where Serra says it:

I think Twombly has a big range– a big range of evocation. I think that’s what he does. He doesn’t present an image; he evokes a sensuality, and it’s unlike anything in post–I think. I’d have to go back to someone like Baziotes, maybe–there’s nothing in the American brain like that. Americans are much–maybe Brice. Americans are much more heavy-handed, much more flat-footed, much more aggressive.

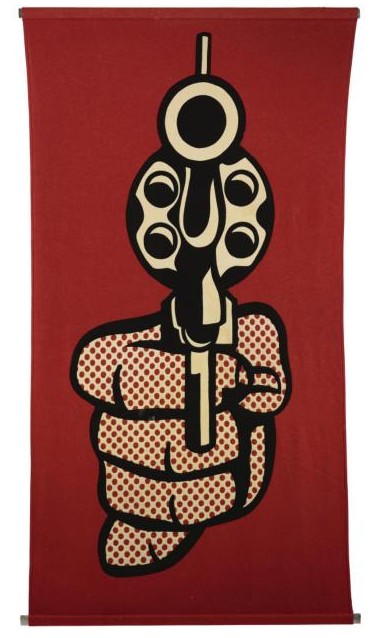

This is the opposite of Cezanne. And the whole inheritance of the New York School kind of goes Cezanne; Cubism; into Abstract Expressionism; Pop Art pretty much hangs things back on a grid; the grid comes back up again in Minimalism. That seems to me all an extension of a certain kind of classicisim and aggression and a standardization coming out of Cezanne, a misreading of Cezanne, albeit. And Twombly takes the opposite attack. It’s very lyrical. And very open. And very…delicate.

Brice Marden: Yeah, I think it’s really great that he left town. [crowd laughs]

OK, then. I seem to have misunderstood the question. The correct answer is actually D) Serra likes to think in terms of major historical frameworks. I’m glad that’s all cleared up.