Untitled (Point Break), 2010, Roe Ethridge, via andrewkreps

This is in Le Luxe, Roe Ethridge’s awesome show at Kreps, through July 3rd.

Related: Crafting Genre: Kathryn Bigelow, a retrospective of the director’s film titles, combined with her early videos, paintings and conceptual artworks, opens at MoMA at the end of May. Point Break will be screening twice in early June, and once in August. [see the complete schedule.]

Category: art

Photomural Collecting Not A Trend Yet

If my intermittent obsession with photomurals, and especially with the actual prints themselves, overlooked objects with a presence and character that feels now like a visual and experiential precursor to the monumental painting and photography of the contemporary era, has jumpstarted any interest in the market for these things, they haven’t heard about it in France.

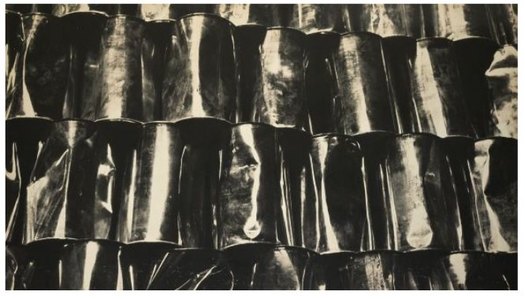

On Monday, Artcurial included this 1964 “monumentale photographie” by Jean-Régis ROUSTAN, a 1.3 x 2.3 meter silver gelatin print of an abstracted wall of dented cans, in its books & manuscripts sale. But it failed to reach even its low low estimate.

LOT 483 Jean-Régis ROUSTAN Monumentale photographie, 1964 1,30 x 2,30 m, tirage argentique sur papier. Encadrement baquette aluminium. Nature morte de boites de conserves cabossées.

Estimation : 700 – 1000 €

Invendu

Tirage unique, offert à l’époque par l’artiste à l’actuel propriétaire. L’agrandissement monumental des boites entraine une abstraction. Légères taches.

Maybe it’s because Roustan was more photojournalist than artist? And though the lot before it went unsold, a set of six vintage prints of 1964 artist portraits by Roustan did sell for EUR829 last December. Duchamp, Calder, Ernst, Dali, Chagall…

But this is still a giant, beautiful, vintage object. I remain confused and convinced, if as-yet unmoved to schlep an 8-foot framed photo by a guy I confess, I hadn’t heard of until last week, over from Paris.

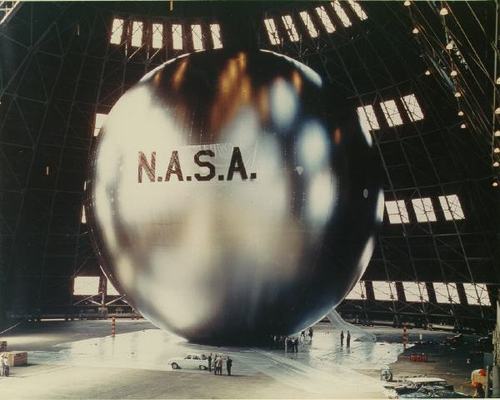

There’s No Escaping Leviathan

Hm, OK.

I think we’re in the clear here, satelloon-wise. It is true that Anish Kapoor’s Leviathan is inflated, and 35 meters tall.

But when you enter the Grand Palais to see Leviathan, you enter Leviathan itself. It’s a space, a bulbous, three-chambered cathedral of a space, “like going into the belly of a whale,” says the Guardian. Though of course, it’s really going into the belly of a cinematic whale. So it’s a belly of imagination.

But it’s a space, not an object. At least, not at first. When you exit, though, it’s a thing. And well, hm. At first, things look pretty grim, which is to say, satelloonish.

But ultimately, it’s a different thing, very different. One thing that’s emphasized in Kapoor’s talk to the Guardian is the light and space of the Grand Palais, and its vast expanses of glass:

“This is a terror of a space, probably much more difficult than the Turbine Hall,” Kapoor said. “It’s three times the size, huge horizontally and vertically and above all the light is a killer. It’s almost brighter than it is outside.”

There are any number of spaces–dirigible hangars, stadiums, train stations–that could hold a 100-ft mirror-skinned aluminum sphere; but in this time, there are no art spaces except, now, the Grand Palais. And that’s part of the point.

Not only can satelloons not escape the problems Gerhard Richter diagnosed for spheres–they’re too beautiful and perfect–they blow these problems up [sic] to gargantuan scale. Which is kind of interesting.

Monumenta 2011 has a Facebook wall [facebook.com]

And Then They Came For The Sarah Morris Origami Paintings

Oh boy, here’ we go again. As @BDPNT, @joygarnett, @robertpearre, @shelawterry, and @Copycense tweeted, “Welcome to Cariou’s world.”

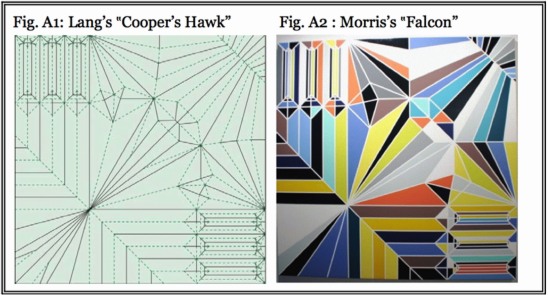

A leading origami artist, Dr. Robert Lang, has filed suit along with several other designers, charging Sarah Morris with copyright infringement for making paintings and prints which use particular crease pattern diagrams without permission or credit.

At issue, just as in Patrick Cariou’s complaint against Richard Prince, is the legal status of Morris’s works, and whether they are derivative, which is infringing, or transformative, which is protected under fair use exemption.

Lang has filed his suit in California, and for some reason a lawyer may be able to explain to me, a great deal of his complaint focuses on the applicability of California as a venue for hearing the case. [The filings, including a sheaf of exhibits, are available for download at Lang’s attorneys’ website. They’re very well-produced, but right now it’s too early to say whether I’d turn them into a book.]

Since I have been exactly 100% [0 for 1] wrong in my predictions for the outcome of such transformative use trials, I’m wary to go too deeply into the facts of this case yet. I will say, though, that basically every difference I see between Morris’s appropriation and practice and Prince’s only intensifies my belief that Morris is and should be in the clear, and that these kinds of lawsuits are a nuisance and a threat. Morris is not an outlier. As an artist she’s operating at the center of the art world, not its margins; her practice and method are widely known, critiqued, supported, and emulated. Within the art world.

She’s also a couple of orders of magnitude less commercially successful, price-wise, than Prince or Koons. As such, she’s more vulnerable than they are, I think, to exactly the kinds of debilitating or chilling effects an expensive, protracted legal fight would entail, especially one fought at an extreme distance. [Morris is based in NYC and London.] Because the stakes for her are non-trivial, they are also more relevant to more artists whose practice includes–I can’t even say appropriation, because I don’t even see Morris’s work within that context. But it’ll be what it’ll be, I guess.

[UPDATE: oh-ho, I may be wrong about this; a couple of people have emailed to point out that Morris is an alumna of Koons’s studio, so this may be exactly the context in which to consider her work. It makes sense, considering the number of people I’ve met who turn out to have worked for Morris at some point. Time to make the donuts.]

Two things, no, three, that stand out, though:

1) These side-by-side exhibits that lawyers for both Patrick Cariou and Lang produced are seductive and deceptive, and they tend to obscure or minimize otherwise potentially important aspects of transformative use.

Lang uses these exhibits to argue that Morris has done nothing but “colorize” [his term] his copyrighted crease pattern. In fact, she has made several substantive changes to its appearance, content, scale, and materials, as well as to its meaning, utility, and context. A crease pattern is not just the geometric form; each type of line–dotted, dashed, or solid–indicates the direction of a fold, and it a crucial, even fundamental element–for making origami. Morris removes all this functional information, a non-trivial transformation.

Another misleading element of these side-by-side comparisons is size. Even if we assume Lang uses the biggest piece of paper mentioned on his site, 20-inch squares, his pattern is still 95% smaller than Morris’s huge painted canvases. A more accurate side-by-side image might look like this:

2) Lang’s filing makes the bold but utterly ridiculous claim that “Morris’s actions have created competition for Plaintiffs by occupying the market for painted versions of their copyrighted artworks.” No such market exists, and I’d argue that Morris’s paintings have created one. If people pay $100,000 or more for Morris’s paintings, it’s not because they look like Robert Lang diagrams; it’s because they look like Sarah Morris paintings. Her realized gain attributable to the origami IP itself is incremental at best.

3) Unlike Prince, who did not profess any particular critical interest in Cariou’s Rasta photos, Morris has publicly discussed and presented her origami paintings as commentary both on origami and its history and its specific meanings and contexts, but also on its contemporary connection to science and systems. Lang the origami expert is famous in a way that Cariou the photographer precisely is not. As such Lang’s work could present a larger, more natural target for someone wishing to make critical new work about origami.

The kicker for all this, is that I’m kind of an origami nerd myself. That my greatest origami accomplishment was winning 2nd prize and $10 at the Utah County Fair one summer when we were visiting my grandparents’ house as a kid pretty much says it all. [I made my origami peacock out of printed wrapping paper.] But I still do it pretty regularly, and I’d say I have an above-average sympathy for these origami masters who feel they’ve been treated unfairly. I still think they’re wrong as hell, though, and that this case is a dangerously unproductive nuisance.

UPDATE: And speaking of my fellow nerds, look who else has spent Friday night picking apart the latest artist copyright infringement case? Joy Garnett has some solid analysis and some biting commentary. I’ll only add that between their blog headline and their PR-chasing email to Newsgrist, the origami folks’ lawyers are really angling aggressively to publicize their claim against Morris.

Lang Origami [langorigami]

Oy: These Origami Artists Won’t Fold [bayoaklaw.com]

Richard Prince Deposition Book All Grown Up

“THE WITNESS: This could be a cool book.”

– Richard Prince Deposition Transcript, p. 328

Dude, Richard Prince just blurbed my book.

Between the lawyers on both sides of Cariou vs. Prince et al, about 275 pages of the transcript of Richard Prince’s 7-hour deposition had been made public as footnotes to various briefs and memos, but there were 101 pages left out.

In the weeks since I compiled the excerpts and exhibits into a book, I’ve been trying to track down the complete transcript. Now I have it, and you can too. After trying multiple sources for obtaining it, a sympathetic party close to the case pointed me to an apparently inadvertent, unmarked exhibit appended to a late court filing, which included the entire 378-page transcript instead of the customary snippets.

And so I have revised Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA to includ the entire interview, in order, with a handy timestamped topical index, even, and with some additional rounds of legal memos, that give a fuller sense of the give and take that led up to Judge Batts’ royal smackdown of Prince’s transformative use claims.

And so I have revised Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA to includ the entire interview, in order, with a handy timestamped topical index, even, and with some additional rounds of legal memos, that give a fuller sense of the give and take that led up to Judge Batts’ royal smackdown of Prince’s transformative use claims.

In addition, to accommodate wholesale requests, I’ve switched printers, so the new, revised edition has slightly smaller page facsimiles, but it is also printed on higher-grade paper. It looks pretty slick.

Because of the additional quality and page count bumps, the cost went up a bit, to $17.99, but it’s still a pretty sweet deal, I think. You can buy Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA directly from Createspace.com, an Amazon print-on-demand subsidiary, of if you like, you can also order it from Amazon. If you’re dying to see it in person first, both Printed Matter and Specific Object have greg.org-stamped copies available.

For folks who have already purchased the book, either in print or electronic format, don’t worry, I’ve got you covered. I made an Appendix which contains all the missing transcript pages, and I’ve been mailing out printed and PDF copies to people who’ve contacted me. Whenever the printed copies run out, I’ll be happy to keep the appendix available via PDF.

Because it really does have some interesting stuff in it, like the quote at the top of the page, which was Prince’s reaction to the exhibit showing the side-by-side comparisons of the Patrick Cariou’s YES RASTA images and the Prince Canal Zone paintings they ended up in. [Obviously, that exhibit is included in the book.]

Now that the whole deposition story can be told, I think I’ll go through and pull out some highlights to share here: some great exchanges, useful insights, or straight-up WTF moments. If you have any favorites, definitely pass them along. And enjoy! The damages hearing is scheduled for May 6, tomorrow!

Buy Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents from Cariou v. Prince et al from Createspace or Amazon.

The book is also available at Printed Matter and Specific Object, both in New York and online.

Tate Something Something Bricks Whatever

I’ve been thinking a lot lately of governments’ relationships to modernism and, by extension, contemporary art, and the controversies that erupt around it.

So I was kind of stoked to see the headline in The Art Newspaper, “Revealed: secrets of the Tate bricks

Newly released documents uncover a heated argument and the search for spares.” The paper apparently filed a Freedom of Information Act request for the documents pertaining to the 1976 outcry over Tate Britain’s acquisition of Carl Andre’s 1966 sculpture, Equivalent VIII, which consists of 120 bricks stacked two high.

Sweet.

But here’s the big get: Tate couldn’t find any extra bricks left to stockpile. Also, “Among the papers is a memo on ‘The Burlington & the Bricks’.”

Seriously, that’s it. Do they publish this long-lost memo or add anything to the Tate curators’ argument in print with Burlington Magazine? No. I guess TAN figures if people really want to know, they can FOIA it for themselves.

Curators Gonna Curate, Politicos Gonna Politick

Tom McCormack’s lengthy look at the contentious, suspicious history of US government support for the arts is worth reading for itself. But it also got me off my butt to write something that’s been bugging me since attending the Smithsonian’s Flashpoints and Faultlines symposium last week.

I had no plans to go to the symposium, primarily because it seemed like such a transparent attempt to ride out the Smithsonian’s “Hide/Seek” censorship mess by throwing up a cloud of bureaucratic, academic dust. While I could be persuaded that Wayne Clough’s resignation over his egregious mistake might have served to embolden entrenched critics and weaken the institution in advance of a difficult budget battle, I didn’t think a pointless symposium designed to corral the most outraged arts administrators into an auditorium and bore the concern out of them doesn’t help either.

But I had a meeting set up with an attendee which got pushed back, so last Wednesday I ended up attending part of the first, museum directors panel, and most of the second, “Exhibitions in National Museums & Public Institutions,” or the political operatives & appointees panel.

From these panels, various references to earlier sessions, and the subsequent, sparse reporting, it seems clear to me that the art world really needs to rethink the paradigm for its relationship with the federal government, or more specifically, with politics.

Frank Hodsoll was President Reagan’s NEA chairman. He was a foreign service officer and lawyer, later an OMB appointee, and now consults. Not an art guy, but a diplomacy-turned-art/culture policy guy. He talked very openly about his charge to vet NEA grant proposals to weed out potentially troublesome, controversial, or poltiical content. He took credit for personally rejecting or spiking a dozen, maybe 20 [I’m paraphrasing, but the video for the panel is archived now. It starts at around 1:40.] proposals that had otherwise passed the NEA’s established panel review process. One example: a Washington Project for the Arts proposal to project images or text or something onto the Capitol Building, which he was sure would anger some Congressmen.

Hodsoll was the Chairman when the exhibition including Andre Serrano’s Piss Christ and Robert Mapplethorpe’s retrospective were both approved for partial or tangential NEA funding. He was very forthright that these projects hadn’t been monitored closely enough, and had he been able to scrutinize them, he would have deemed them “inappropriate” and denied them funding.

I guess I was not so amazed that the chairman of the NEA was advocating actively screening and denying grants based on the ideological or political appropriateness of the artwork, but that the NEA was screening out work that might engender controversy or displeasure from congressional representatives. It was a position and policy that rejects not only the possibility that art might have political content or engagement; but also art’s essence as an expression of speech.

Putting it in terms of whether this or that project is deserving of taxpayer support misses the point, at least when such support exists. Hodsoll pointed out that artistic expressions get rejected all the time, “it’s called selection,” by which he meant the NEA’s grant evaluation processes, but also, I think, curation.

And so the tautological calculus that art may receive public funding if it wholly disassociates itself from politics and/or controversial issues, and if it pleases–or at least doesn’t piss off–someone in the government. And if these terms aren’t acceptable, art, artists, and art institutions can deal with the reality that the government has no responsibility or compelling need to support art anyway.

If this argument wasn’t disheartening enough, Hodsoll was followed by Bill Ivey, who was Bill Clinton’s NEA chairman, the guy left holding the mop–or left holding the bag–after the fiercest Helms-led attacks on the NEA. Ivey spent almost half his time laying out the findings of various polls that showed no matter how you slice it, 30-50% of the population does not support the right to free speech.

Never mind that the right being opposed is always someone else’s, and the speech is something they disagree with. With such tenuous support, an inconsistent and unfriendly legal landscape, and the existence of politicians and/or activists who will exploit this rift, Ivey argued, the last, most important thing is to protect the institutions of art, and their funding. [In a perfect segue, the next panelist was Ford Bell who, as president of the American Association of Museum, is basically the art institutions’ lobbyist.

From the far side of long careers as political operatives and appointees–only Bell seems to have ever run for elected office–these men uniformly decried the politics, and the politicizing of art and museums–by others. Just as propaganda is the other guy’s marketing, playing politics is someone else’s common sense policy. The only winning move, we’re told, is not to play. A strange game indeed.

And Ellen McCulloch-Lovell, the moderator, opened the panel with a lament that I hear so often, it’s like the Washington art world’s Pledge of Allegiance: “I wish there members of Congress could hear to this.” But they never are.

No wonder the official art world wants to see itself apart from politics; to do otherwise only proves how poorly they do, or how superfluous they are. At least in the nakedest political terms of power and money.

As infuriating or disheartening as these political hands’ assessments may be to an art lover’s ears, they are still important to hear. They’re experienced views from the real, political world of Washington, the world in which money and constituents and lobbying and controversies and demagoguery and negotiation and propagandizing exist. Symbolism is there, too, and dissent, and relationships and persuasion.

If art & museum people thing politics seems intimidating, confusing, or potentially embarrassing, maybe it’s worth recognizing that many non museum people, politicians included, feel the same way about art.

The “Hide/Seek” Wojnarowicz crisis was precipitated by a conservative religious and political activist who had no interest in art, but in changing the political micro-climate during the congressional vote to end Don’t Ask/Don’t Tell. Clough reacted to soundbites solicited from political staffers who saw neither the show nor any political downside to criticizing it and the Smithsonian which sponsored it. By so doing, they only raised the political price their opposition would have to pay for their funding levels and priorities.

Throughout the Flashpoints Symposium, speakers referred to Hide/Seek co-curator Jonathan Katz’s rallying cry that Americans would rise up to defend their/our Smithsonian from the threat of budget cuts [or worse.] But that seems as practicable as wishing there were more senators attending your 2-day symposium.

Through the efforts of some combination of, in order of mobilization, directors, boards, curators, artists, educators, marketers, associations, audience and constituents, lobbyists and legislative affairs professionals [that’s everyone, right?] I think the art world needs to make a more compelling political case for itself, and to make it more persistently and productively. I have some sense for how that might happen, but at the moment, it still feels like a major endeavor to accurately understand the problem.

Where is that Leviathan, whom thou hast made to play therein?

So all this time, I’ve assumed it’s common knowledge that I am planning to recreate a satelloon and exhibit it in the nave of the Grand Palais in Paris. And if the curators of Monumenta, the annual contemporary art installation there, hadn’t called about it yet, it was just because they were busy clearing the older guys [Kiefer, Serra, Boltanski] off the list first. Which is fine, of course. No rush.

But then I get this tweet about Anish Kapoor’s project, which opens next week, and well:

You can understand my concern. So I “c’est quoi ça?” retweeted, and then I started poking around the Monumenta 2011 site more carefully.

And before I figure out if Kapoor’s workin’ my side of the street, I have to say, I’m now slightly fascinated by the mechanism of the teaser, the reveal, and the spectacle.

Monumenta has assembled a range of concepts and images highlighting aspects of Kapoor’s practice which, I assume, they see as relevant to or illuminating of their own commission.

Artwork become landscape

Artwork become landscape

To see is to imagine

Entropy

Self-generation

The écorché

Fiction and ritual

Concaveness

Light become ghost

Void become shape

The artwork skin

Non-object

Colour

Inhabiting space

Leviathan

I can’t help but imagine them as a narrative, a presentation, an argument that culminates in the essential, inevitable work. Leviathan: c’est logique!

The work is called Leviathan, and with references to sea serpents and gargantuan invaders and gaping maws, the write-up taps every ominous, apocalyptic Leviathan reference available, from Job to Hobbes.

Which, now that you mention it, does sound a lot like several of the works Kapoor has done before. And there’s this sense of simultaneously wanting something new, that no one’s ever seen before–oh, boy, will they be surprised!–and of wanting more of what works, what you know, what has been before. And then what is the nature of anticipation and experience when the pitch for the project is, “it’s like Marsyas at the Tate, but bigger and spookier”?

So I’m basically thinking it’s the Doomsday Machine from Star Trek: The Original Series, but in red? Or mirrored? Or mirrored on one side, and red on the other:

And then today, there’s a teaser photo, a detail, on Facebook, which doesn’t quite match up to my image:

Unless maybe it’s the Doomsday Machine’s nuts. Either way, it’s all good, and totally different. Still, it’s an important lesson learned, and I’ve decided to preserve a bit of the mystery surrounding my Monumenta project. Which is not to say anticipation.

![]()

Monumenta 2011 au Grand Palais, 11 Mai – 23 Juin [monumenta.com via @Monumenta2011]

Could Be?

via Eyeteeth | “File under: This could be art”

Can’t tell you how awesome this is. I would pay cash money to see the biennial that shows it.

The US Expo 67 Pavilion Has Seven Fathers

I’m getting pretty comfortable with my love affair/obsession with the US Pavilion at the Expo 67 in Montreal. I mean, it’s got Buckminster Fuller; Alan Solomon curating gigantic paintings; photomurals; and satelloons, what’s not to love, right?

So seeing Design for a Fair, the 1968 promo short film by Peter Chermayeff is awesome just as it is. The vintage footage and photos are some of the crispest I’ve seen, and it really is pretty crazy on a whole bunch of levels that this thing existed at all.

But maybe the greatest thing–even better than the giant graphic designed flags that look like a lost Ellsworth Kelly, as if there wasn’t enough giant, escalator-optimized, actual art already–and even better than the sheer soft power/propaganda play that was so drop-dead awesome it won the future for the day–is the voiceover.

Because the whole thing really sounds like Chermayeff’s idea. Every last bit of it, dome to nuts. It’s fantastic. Chermayeff, of course, is an architect and exhibition designer, and his former firm, Cambridge Seven Associates, or C7A, was contracted by the US Information Agency to produce the US Expo entry.

And so, as Chermayeff tells it, they knew they wanted a 3/4 geodesic dome, so they ordered one. And they wanted some giant art, so they ordered that. And the moon stuff, and the Hollywood and all the happy parts of American culture.

Now I don’t doubt a thing; I’m sure that’s exactly how it all went down. It’s just that that’s not how it’s typically remembered. Architects only remember Fuller; the art world only recognizes Solomon and the artists, not the venue or the show or the implications of it; and everything else is artifact and prop. [And the poor lunar photomural, I’ve hardly found anyone remembering that at all.]

The historical focus is either on the general awesomeness of the spectacle and mood, the political context and propaganda, or on the parts in isolation. What Design for a Fair reminds me of, though, is the visitor’s experience, the carefully orchestrated messaging, and the reality that it was orchestrated by a contractor working to a brief provided by the USIA. It was a government-funded gesamtkunstwerk, a massive piece of installation art before the fact, and probably one of the most cost-effective public diplomacy efforts of the Cold War era. It literally seems unimaginable today.

Tuymanmatic

The greg.org Evening Sale

Flipping through the lots for Christie’s upcoming contemporary sale feels like diving into the greg.org archives. Besides the Rauschenberg combine coming out of the Ganz’s closet, there’s also:

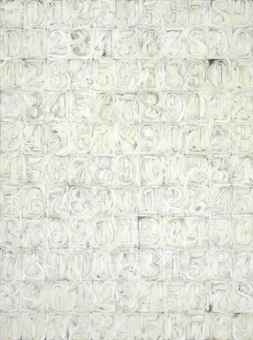

a great Johns White Numbers painting (1991) by Sturtevant. This text is nice, too:

To create her paintings, Sturtevant does not copy. She does not employ grids, squares, tracing paper or cameras. She summons her memory of images to recreate and reinvent them. By obsessively utilizing the identical materials and techniques as those who came before her, Sturtevant asserts her work is not about copying or appropriation, rather, the power and autonomy of originality.

Love that, so Pierre Menard.

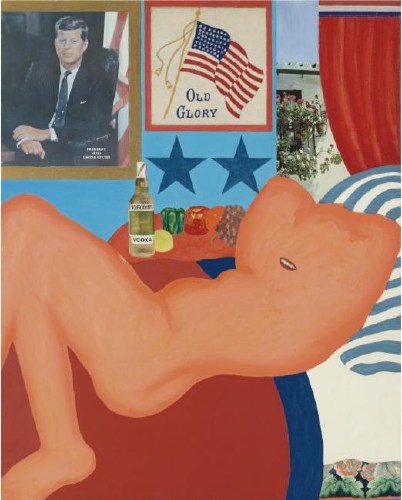

Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude #21 (1961) is up for sale again, too. In her biography of DC artist and JFK mistress Mary Pinchot Meyer, author Nina Burleigh mixed up #21 with #44. It was the former, not the latter, which was the subject of some controversy in Washington when it got yanked before the opening of the 1963 Gallery of Modern Art exhibit, “The Popular Image.” Burleigh said Meyer whispered about it to JFK, who laughed and kept it in. The painting in the show. But I looked it up, and no. The painting stayed out, probably because it included a nude next to an image of the sitting president. Or something. Anyway, censorship! Scandal! Sale!

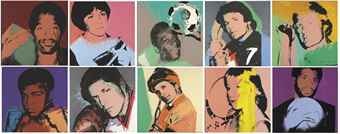

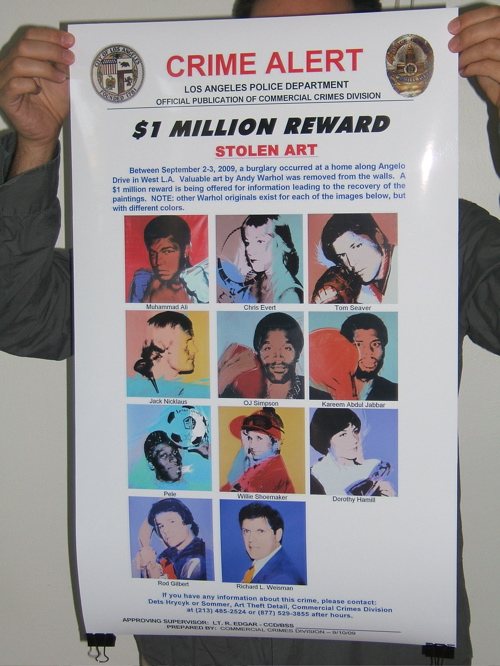

And speaking of scandal and mystery, Los Angeles collector Richard Weisman is apparently selling one of his remaining sets of Warhol Athlete Series paintings, which he commissioned en masse back in the day.

They’re like the set that was reported stolen from his dining room a couple of years ago. The disappearance of which prompted LAPD’s art theft unit to release the awesomest wanted poster ever. Which I tried to Kickstart into production as the Find The Warhols Project, only Kickstarter and I had apparently not developed our audiences sufficiently to accept the idea of a project-as-critique. And the reward for which was discontinued anyway when Weisman decided to drop his insurance claim, because of the investigative hassle. Which art theft experts read as a sign that the theft was an interfamily job, and not the kind of thing that one likes to have reported out in all the papers if one can help it.

But it’s not that set; I checked. Instead, it’s the set Weisman tried to sell in China during the Olympics for $28 million. Now priced to move, with an estimate of just $4-6 million. Also, too bad the Warhols don’t need finding anymore; that poster looks really sweet. Guess I’ll save it for the retrospective.

Mister Rauschenberg’s Neighborhood

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The costumes for the production were designed by Rauschenberg’s partner Jasper Johns.

Did I say partner? I guess I meant neighbor. Here’s Christie’s quoting Paul Schimmel from his 2005 Combines exhibition catalogue:

While Rauschenberg’s work does respond to the painterly traditions of the 1950s, it does so in a manner that isolates the act of painting from the complete composition. For him, painting became a thing, an object treated similarly to Assemblage in which elements were organized on a non-hierarchical surface. Rauschenberg took aspects of Picasso and the Cubist collage, Kurt Schwitters, and the Surrealism of Joseph Cornell and created a three-dimensional, collage-based art. Together with Jasper Johns, Rauschenberg defined the American art of the 1950s; Pop art would have been inconceivable without their respective breakthroughs. Incidentally, many of their most important advancements were devised when they were most closely associated, living as neighbors, during the second half of the 1950s-the period during which The Tower (1957) was created.

[emphasis added for salient points regarding Short Circuit and for WTF, respective? Incidentally? Neighbors??, respectively.]

Schimmel goes on to note that the appearance here of a broom “anticipates Jasper Johns’s use of the broom in Fool’s House (1962), at a time when they were no longer neighbors.” Yet while he notes that “Lights and bulbs,” one of the defining elements of The Tower, “recur in numerous works”–of Rauschenberg–the fact that just months later, while they were still, uh, neighborly, Johns chose a light bulb as the subject of his first sculpture goes completely unmentioned.

Light Bulb (I), 1958, Jasper Johns, image: mcasd.org

Here is Post-War & Contemporary Deputy Co-Chair Laura Paulson in a gallery talk video,

The Tower is very autobiographical, using found imagery, found objects that would give you clues to aspects of Rauschenberg’s life. Rauschenberg was a gregarious, outgoing, very generous person, but he spoke often in sort of cryptic, very defined ways. And in Tower you have this sort of personage, which to me is just so perfectly Rauschenberg, you really feel this inside/outside aspect of it. And to me, that really defines how his art was: very autobiographical, giving you clues, but not necessarily the full story.

You don’t say.

It’s a little bit funny. One reason I’ve stayed so interested in Short Circuit has been the implications of finding the original Jasper Johns Flag on the creation myth of Flag itself. Because really, what would it mean if Johns’ first flag painting was actually shown inside his boyfriend’s combine? And he didn’t even get credited for it? What if Johns’ idea to paint the flag came from the same place as his idea to paint the map, Rauschenberg?

But what if it goes both ways? The Tower, Schimmel writes, dates from “the middle of Rauschenberg’s Combine period, which extends roughly from 1954 to 1962.” Which is, incidentally, also the period Johns and Rauschenberg were a couple. What if combines came from Johns? Or silk screening?

Or maybe it’s not so simplistic or binary. Maybe “their respective breakthroughs” were collaborative? Maybe they talked through and worked through “their most important advancements” together? How does Target with Plaster Casts relate to the combines of 1955? Or how do the combines relate to Johns’ object-laden paintings of the post-breakup era? What do the famously autobiographical, emotionally-charged-yet-obdurate works of these two artists reveal about each other, their life together, their production, and the culture in which they lived?

For three generations now, the art and art history worlds have been arguing for the separation of these two artists and the distinct, unknowable power of their “respective” achievements. Some day maybe we can tell the full story.

Lot 28, The Tower, 1957, est. $12,000,000-18,000,000 [christies.com]

The Free Speech Movement Monument Was Censored.

In 1989, a group of veteran activists organized the Berkeley Art Project to create a monument marking the 25th anniversary of the Free Speech Movement. Mark Brest van Kempen’s conceptual proposal won the elaborate national competition and dialogue. It is a 6-inch diameter circle of earth surrounded by a granite circle that reads, “This soil and the air space extending above it shall not be a part of any nation and shall not be subject to any entity’s jurisdiction.”

Remarkably, the Berkeley University administration only accepted the monument on the condition that any reference at all to the Free Speech Movement be stricken from the work and any surrounding publicity.

A podcast I’d never heard of but really like now, 99% Invisible, has the story of the Free Speech Monument, and an interview with the artist.

For added perspective, check out the 1992 statement by FSM leader Michael Rossman, who opposed the selection of a conceptualist monument–until Berkeley’s president added to its conceptual power by censoring it:

If this story be remembered as part of the work, it will stand for the ages, or until a censorious jackhammer erases it from the Plaza. A century hence, our descendants may read the truth written in stone: What happened here in 1964 was so significant and so deeply contested that nearly thirty years later the university administration still would not permit faculty and students to honor its name, but instead insisted on censoring their political expression. In this perversely perfect monument to the FSM, they may read a larger truth applying far beyond the campus: that the issues opened in that conflict and era, of civil liberties and rights, had still not been resolved, but continued deeply contested.

The Invisible Monument To Free Speech [99percentinvisible.org via someone awesome I can’t remember who, but probably Geoff Manaugh, since he’s the subject of the previous episode]

The Berkeley Art Project, by Michael Rossman [mrossman.org]

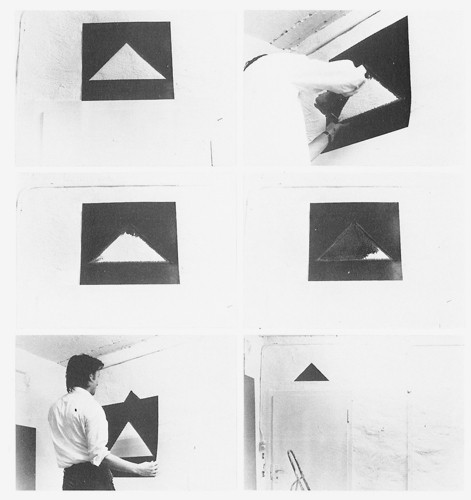

Pass It On

In 1969, Rene Block in Berlin published Blaues Dreiecken, Blue Triangle, an instruction-based edition by Blinky Palermo. It includes a large triangular stencil, a tube of blue paint, a brush, and a print made with same.

The instruction sheet reads, “Malen Sie mit Hilfe der Schablone ein blaues Dreieck über eine Tür. Verschenken Sie dann das Original Blatt.” [“With the help of the template, paint a blue triangle over a door. Then give away the original sheet.”]

image: editionblockberlin.de

I wonder how often that has happened. The example shown at the Hirshhorn’s Blinky Palermo retrospective still includes the original print; the tube of paint looks undepleted, and that stencil doesn’t look like it was used to paint anything, including the triangle over the gallery doorway. [UPDATE: alright, I happened by the Hirshhorn again today, and took a closer look; the stencil does seem fresh, but the brush has been used at some point. And maybe the paint, too? Maybe Blinky painted each triangle print with the set itself? I hate ending everything with a question mark. This was 46/50, from Block, btw.]

All of which should surprise no one, I guess, conservators and exhibition practices being what they are.

Does anyone ever actually execute these things? Complete the artist’s instructions and realize, presumably, their intentions? Or have market forces condemned these kinds of works to permanent potentiality?

A Blue Triangle sold in Berlin for EUR34,000, and though it still contained the original, giveaway print, at least it did “contain traces of use.”

In 2009, artist Pierre Leguillon translated Palermo’s instruction to mean “give away the stencil,” and so he started just paintin’ Blue Triangles over doors all over the place. [Though it doesn’t appear that he used a Palermo edition, or even a stencil at all; he just taped them off. C’est complique.]

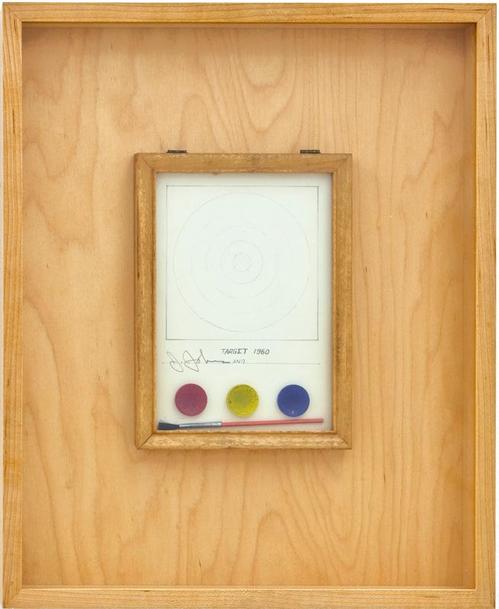

Do It Yourself (Target), 1960, Sonnabend Collection, image: MADRE

In 1960, Jasper Johns created Do It Yourself (Target), a framed drawing/diagram and collage of paint pots and brush. Given the artist, date, and that it’s a unique work under glass in his dealer’s collection, I would suspect that the denial of the invitation to collaborate is central to the work.

And yet, what happened to Target 1970, a mass-produced multiple similar to Do It Yourself (Target), which was included in MoMA’s catalogue for a 1971 Gemini G.E.L. retrospective? Those books are occasionally misdescribed as signed Johns editions [the signature is part of the offset print], and they’re offered for between $2500 and $75. Yet, even so, I’ve never seen one executed.

Does that mean the contingency of the void has been successfully translated to a different market segment? Or just that no one ever bothers to try to resell the “used” copies? Maybe it’d be interesting to buy a few of these Johns things, and give them to folks to execute.