Washington Post art critic Blake Gopnik commenting on the tiny chip of porcelain Eva and Franco Mattes, the formerly anonymous artists behind 0100101110101101.org, reportedly took from one of Marcel Duchamp’s urinal sculptures:

In the case of Duchamp’s “Fountain,” could it be that the Italians are actively helping his art do its work? The Duchamp urinals we now see in our museums are visibly handcrafted replacements for his mass-produced industrial original, which disappeared early on. By pawning off a piece of handicraft, made by a hired artisan, onto his collectors, I think Duchamp was poking fun at any fool who insisted on getting an “original” Duchamp, instead of heading to their neighborhood plumbing supplier. The chip of porcelain in “Stolen Pieces” is an extension of Duchamp’s chipping away at precious art and its status as collectible commodity.

Ah, um, no.

Actually, as has been reported recently by no less august a source than The Economist, Duchamp’s Fountains replicas include two or three actual, vintage urinals Duchamp signed, showed, or sold; and somewhat more than twelve which were cast, just as porcelain is, from a clay sculpture [aka “the prototype”] made from Arthur Stieglitz’s photo of the “original.”

16 are included in Duchamp’s catalogue raisonnee, including the lost original and a presently lost 1953 reproduction, but not including the prototype or the additional casts Duchamp’s dealer Arturo Schwarz apparently made and has been shopping around privately.

Now to Gopnik’s fools. Here is a list, as compiled by Cabinet Magazine in 2007, of traffickers and current owners of Fountain:

- The Philadelphia Museum of Art

- Moderna Museet, Stockholm

- San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

- Tate Modern, London

- National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

- The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

- Dina Vierny Foundation– Maillol Museum, Paris

- Indiana University Art Museum, Bloomington

- National Museum of Modern Art, Pompidou Center, Paris [which has been both pissed in and attacked with a hammer since the Matteses’ own assault]

- The Israel Museum, Jerusalem

- National Gallery of Modern Art, Rome

- Duchamp dealer and MoMA trustee Sidney Janis

- Duchamp dealer and edition publisher Arturo Schwarz

- Larry Gagosian, who sold one to its present owner

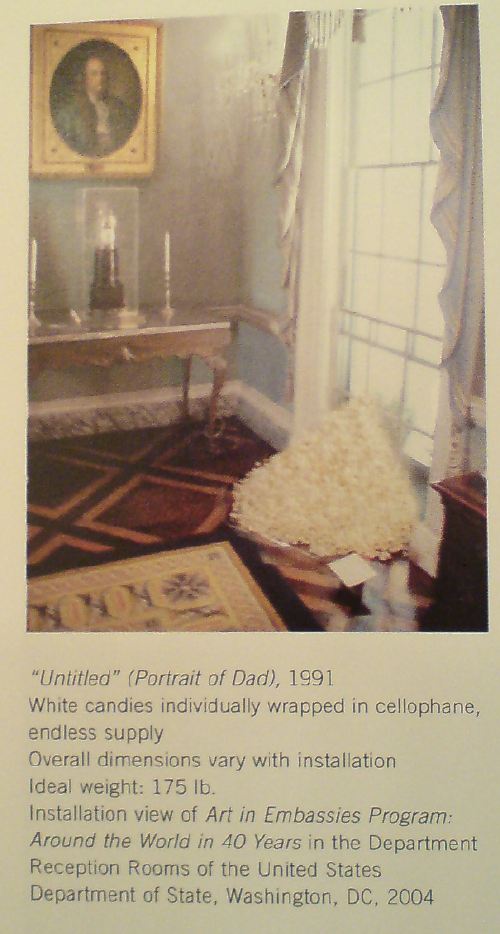

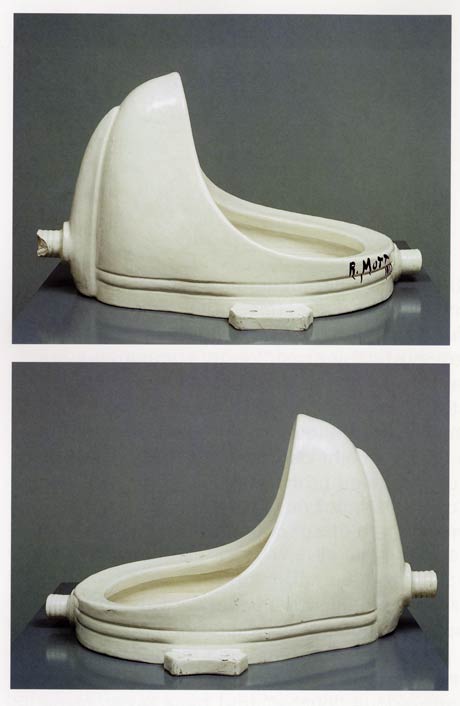

Three are in private collections, not including Schwarz’s extras. The prototype was sold to Andy Warhol in 1973. Dakis Joannou purchased it at Sotheby’s auction of Warhol’s estate in 1988. In case you couldn’t tell, that’s the prototype up there, glazed and signed just like the rest of them.

Which ones of these does Gopnik consider fools and the butt of Duchamp’s joke? The Moderna Museet, whose Fountain was donated at Duchamp’s request? Or the Philadelphia Museum which, thanks to the Arensbergs, indefatigable Duchamp collectors and supporters for decades, now houses the largest collection of the artist’s work in the world, and which was secretly chosen by him as the posthumous recipient of his elaborate, last work, Étant donnés? All the rest? Or just all of them?

update:At AFC, Paddy has a great 1961 quote from Duchamp about his object selection criteria. Me, I unfortunately started my period commentary search in the 1973 Duchamp retrospective catalogue by Anne d’Harnoncourt and Kynaston McShine. But so far, it’s really thin. So much effort appears to be devoted to his surrealism and his traditional works: drawings, etc., that really strike me as uncompelling. Funny what a couple of generations of soaking in interpreted Duchampisms will do to a discourse.

Anyway, my point, I hope it’s clear, was not just to harsh on Gopnik, but to correct what I believe to be an inapt and unsupported claim that Duchamp considered buyers of readymades (et al) “fools,” or that they didn’t know what an “original” meant in the artist’s context. Just consider how many boites en valise he published. I’m happy to be set straight, but I believe that Gopnik doesn’t have a clue that he’s basically implying that Duchamp’s entire object-based oeuvre is a prank–which the leading museums of the world have apparently fallen for for fifty+ years.