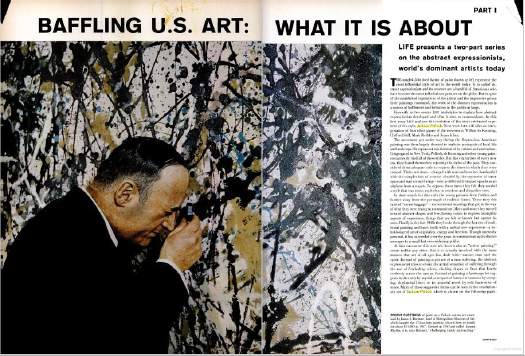

Can I just suggest that, when you buy an article from the New York Times Archive, you go ahead and buy a 10-pack? In addition to supporting your local paper in their time of financial distress and dire need [ahem], you can use the other nine articles for exploring whatever random people, thing, or history crosses your mind?

Which is how I found Roy Bongartz’ Sunday arts feature from August 11, 1974: “Question: How Do You Buy A Work of Art Like This?/ Answer: With A Check”

The piece could’ve been read straight in one of Powhida and Dalton’s #class sessions. Burden, Beuys, LeWitt, Acconci, de Maria, Bochner, Ray Johnson, Ian Wilson:

…these artists, all of them young “conceptualists,” had decided to lift their work clear out of the category of investment property. By shifting the emphasis of their work to the pure thought and by refusing to offer any saleable object, they were mounting a deliberate attack on the traditional business of art. The artists’ intention was to leave the dealer with nothing to sell, the collector with nothing to buy, and the museum with nothing to squirrel away.

[turn page, see continuing headline, “Buying Conceptual Art – Photos, Sets of Directions, Receipts”]

…The secret is that there is always something to sell.

Artists need to eat. Collectors want to buy. Ronald Feldman “authenticates” Burden’s gunshot wound with a check. And voila! These rebels’ most cunning attempts to escape or destroy the art market have been thwarted before brunch. We can now move on to the crossword.

But beyond the apparent news-worthy novelty of certificates, documentation, and instruction-based work, and the vastly divergent view now of some of the namechecked artists–Ryman and Sandback have a conceptualist collectible object problem?–you know what the funniest thing about the past is? It’s the little differences:

That as long as the instructions [which sell “for as much as $8,000”] are followed, “it doesn’t matter at all whether it’s you, Sol LeWitt or your Uncle Elmer who does the marking.”

That dealer/wife Mrs. John (Susan) Gibson is aghast at an invitation “from a Washington DC gallery” to show Robert Cumming’s text & photo-based work–wait for it!

–in the photography section! Mrs. Gibson insisted Cumming’s work go into the fine arts section because he was not showing photographs, but conceptual art. The reply was, well, we hope this is what photography will become. “Too late,” said Mrs. Gibson. “This is what fine art has become.” It was a standoff–no show for Cumming.

And then there’s the eerie familiarity of Ian Wilson, “a kind of extremist even in SoHo, [who] simply comes in and talks. This is all that he does, and he’s made a career of it.”

The quote is from Sonnabend director Ealan Wingate:

“Here the art becomes so abstracted there is no object whatever. Yet in a way there is always an object because an idea can be a subject. [hey, wait– -ed.] There is, also, always the piece of paper, the bill of sale, which says you bought it.”

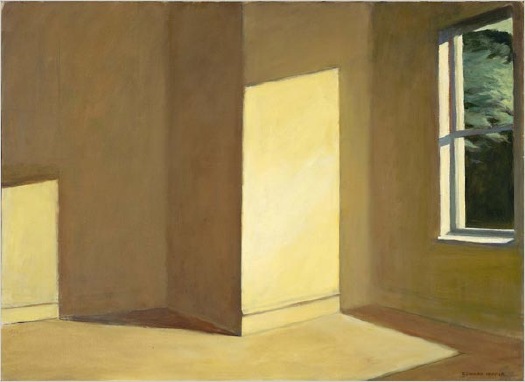

And then comes Bongartz’ explanation of the paper gauntlet Wilson threw down across the ages to Tino Seghal:

You can commission Wilson to do a piece; for example, he may come to your house and talk with you about Plato for a while. The two of you might discuss, say, the subject of unreality, and that would be it–and you’d get your receipt.

For all the fun of digging through the Times’ archive on my own coin, it’s not all eye-opening, perspective-correcting or knee-slapping blog fodder. Even at $1.50, you sometimes click through to a dud, but overall, it still feels like money well spent. And not just because seeing vintage discussion of an under-remembered predecessor should at least cast a critical shadow on the current hype over Seghal’s artistic innovations.

There’s an extra, bonus level of irony, though, in paying to read a 36-year-old Times article about artists successfully selling nothing–and then in worrying that I’m quoting and recapping it too much, thereby damaging the damaged Times’ economic position, or at least earning me the wrath of the copytheft maximalists.

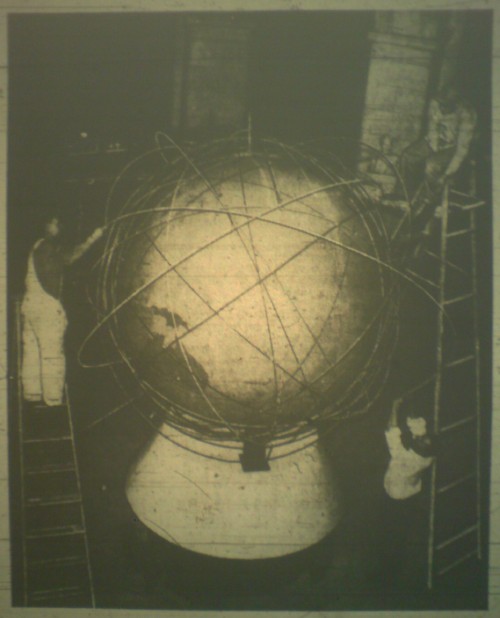

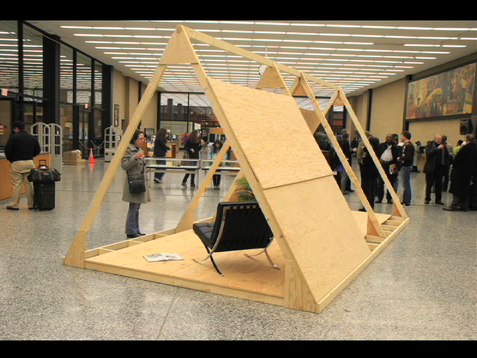

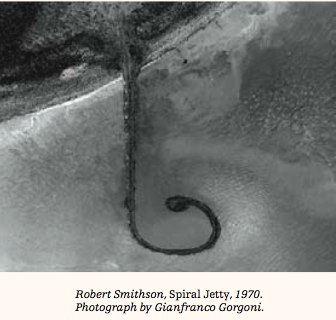

But, oh, look, here’s the whole article for free online. Apparently, the Times repackaged a bunch of arts coverage in 1978 as a topic-based anthology. Which was scanned into Google Books. Of course, it’s formatted differently, probably from a different edition of the paper. So it doesn’t have the $1.50 PDF version’s awesome illustration of Wilson’s work:

The secret is that there is always something to sell.