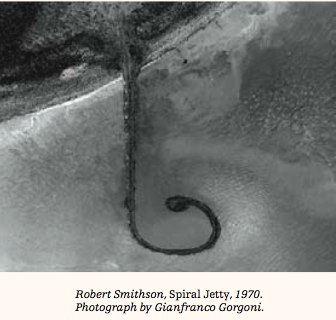

For a generation of art watchers, Robert Smithson’s Spiral Jetty existed primarily as an image, via the making-of film and Gianfranco Gorgoni’s iconic aerial photographs, which were exhibited at MoMA’s seminal Information show and were published in Smithson’s Artforum essay on the work. This mediated encounter with the work inevitably affected its interpretation. But similarly, the 16 years of visibility and visitability since the Jetty’s re-emergence from the Great Salt Lake can lull you into a sense of complacency that you now know the work. And by you, of course, I mean me.

The latest issue of the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art Journal includes an excellent essay, “Spiral Jetty through the Camera’s Eye,” by doctoral candidate Kathleen Merrill Campagnolo, which looks at how Smithson used photography and film to shape not only the reception of the Jetty, but its conception and evolution as well.

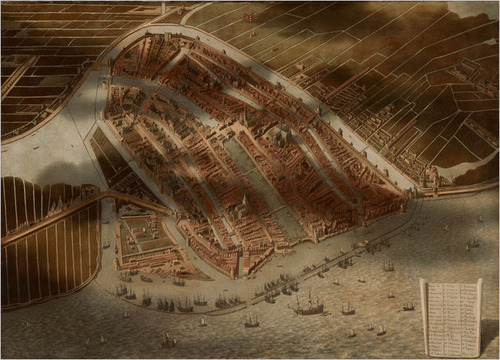

For example, at first, and even until a week after it was supposedly completed, it wasn’t actually a spiral. The image above is from a contact sheet Gorgoni took in April 1970. It shows the Jetty:

…with a single, simple curve to the left, creating a hook shape with a large circle of rocks at the end…In a recently published account of the construction of the sculpture, the contractor Bob Phillips reveals that Smithson considered this first curved jetty, as seen in Gorgoni’s photographs, to be complete, but about a week after the construction crew had been sent away, he called them back to alter the configuration…

…Not surprisingly, the early version of the sculpture was not included in any of Smithson’s Spiral Jetty works. In fact, by the time he had finished his essay in 1970-71, the text reads as if the form the jetty took was a foregone conclusion from his first arrival at Rozel Point.

Campagnolo’s article has another Gorgoni photo, of Smithson and Richard Serra looking at a lost/destroyed sketch of Jetty v1.0 with v2.0 superimposed on it.

To see the sketch, you should really read the article. But I am reproducing the top half of the image here because I am in awe of Serra’s impressive Jewfro.

PDF: Vol 47: 1-2, The Archives of American Art Journal [aaa.si.edu via the Archives of American Art Blog Really? Yes. It’s awesome. [blog.aaa.si.edu, probably via tyler green, since it mentions hockey]