I can’t say how I feel about Francesco Vezzoli’s work; that’s not how my mama raised me. I will grant though, that he’s extremely smart and astute and has successfully identified an elemental dynamic of the art world and makes highly successful art that taps into that dynamic. OK, fine. his work embodies almost every superficial, vapid, self-unaware, pseudo-celebrity, luxury consumerist aspect I hate about the VIP Preview art world.

So bully for him that he’s turning the MoCA gala benefit tonight into the set for a performance/piece? This faux-ambivalent account of Vezzoli, his date/star Lady Gaga, and the preparations for the event in the LA Times makes for hilarious reading. I’m sure the event will be the biggest, starchasing cluster$%#& at MoCA since Tom Ford and Naomi Campbell turned the Takashi Murakami dinner into a commemorative plate-stealing riot.

Alas, Vezzoli’s use of art to hustle celebrities into working for free unfortunately reminds me of someone I actually like: Robert Altman. To shoot the benefit scene in The Player, where Tim Robbins’ murderous studio honcho Griffin Mills is honored by several hundred of his best celebrity friends, Altman threw a real fundraiser for LACMA, complete with black & white dress code, then hustled all his celebrity friends to attend–then he filmed them for scale for his movie.

At least now I can finally make sense of Lady Gaga: she is post-op Cher.

Francesco Vezzoli escorts Lady Gaga to MOCA’s gala [lat]

Category: art

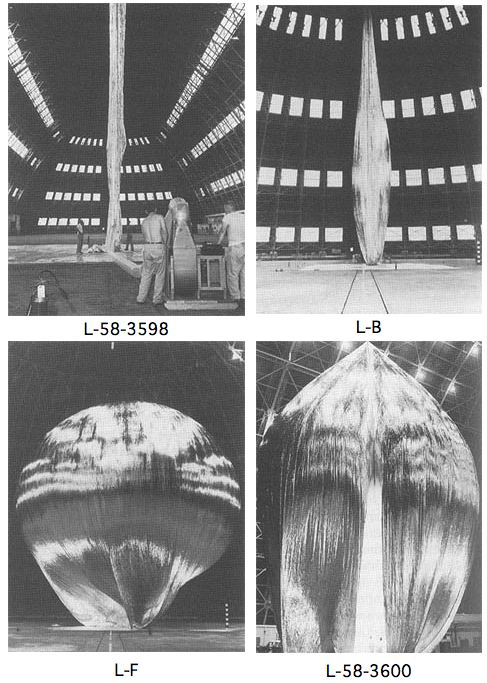

Project Echo & Satelloon Conservation

The first Project Echo satelloon may have started out as a 100-meter sphere, but it didn’t stay that way. Echo IA launched on August 12, 1960, and it stayed in orbit and visible to the naked eye until May 24, 1968. It inflated successfully, but as a paper in Bell Labs Report, Sept. 1961 explains, by May of that year, its shape had already been somewhat deformed in orbit:

On several early passes the average “scatering cross section” was equal to that corresponding to a perfectly conducting 100-foot sphere. From this it is assumed that the balloon inflated as planned.

There apparently has been a long-term decrease, of a few db, in the average “scattering cross section.” As of last May, Echo I [technically IA, since Echo I burned up soon after launch in March 1960] was probably an approximately spherical object with a diameter of no less than 70 feet, and a somewhat wrinkled skin. There may have been a few flattened areas, as indicated by occasional deep fades in the radar signal, but voice communication was then still possible as shown by successful tests with NRL on May 25.

One factor may have been the solar sail effect, the slight pressure generated by photons from the sun bombarding the satelloon’s skin.

image: The Odyssey of Project Echo [history.nasa.gov]

What I Looked At Today – Alex Brown

Though they’re pixelated abstractions, and though they’re almost as likely to be landscapes as people, Alex Brown’s paintings feel a bit like the opposite of what fascinates me about the Dutch Landscape paintings I’m working on.

From a q&a with Brown that accompanied his most recent show this February at Feature:

.who or what are some of the things that inspired your interest to have your work delve into the interdependent relationship of representation and abstraction? Lack of skill as a painter in a more traditional sense of the word? Unwillingness to give you a clear picture of what’s really going on in my brain?

That relationship is a direct result of the manner in which I have chosen to paint. I have always been confused by abstraction. Confused because of a lack of orientation. Taking something realized and turning it into something unrecognizable makes sense to me. I try not to think in those terms so much. They’re all just paintings and some look more like something that you’ve seen in your experience than others do. It all trickles down in varying degrees from a clear source image to finished painting. My abstractions are really just less than overly clear realizations.

Brown developed his approach after realizing he can’t paint straight; he deploys a grid and a filter on an undistorted source image, then painstakingly transfers the result to canvas. I imagine it’s a process similar to Chuck Close’s, whereby a photo is reconstituted, pixel-shaped abstract blob by pixel-shaped abstract blob.

But the distorting abstractions that unmoor the image from its specific subject and turn it into a painting are all Brown’s. The abstract polygons in these Dutch Camo Landscape images have all been put there by someone else–who wants to obscure and despecify the underlying representation. In an odd, inverted sense, paintings of them will look abstract, but will be representational.

Anyway, there are many more wonderful images of Brown’s work at Feature’s website. Above: Fairgrounds, 2008 [featureinc.com, thanks 2 coats of paint for the reminder]

What I Looked At Today – Hiropon Factory

![]()

I didn’t realize it until I surfed across this half-pixelated Takashi Murakami painting, but I have Murakami’s factory lodged in my brain as a model of digital-to-analog painting and production.

Back before the whole Louis Vuitton thing, even before Kaikai Kiki, I used to go to Hiropon Factory, Murakami’s Brooklyn studio, somewhat regularly. It seems quaint now, compared to the scale of the Murakami machine. But there’d be teams of painters carefully translating computer-generated illustrations to canvas, one mixed-and-matched color at a time. It was a Superflat paint-by-numbers.

For all the hype, there’s something refreshingly cynical about Murakami’s practice, which I think looks quite different in a Japanese/Asian context than it does from within the Western Art World.

The group show this painting was in, “Hi & Lo,” was curated by trendchasing fashion guru Hiroshi Fujiwara at the Kaikai Kiki space last October. It included Murakamis and works from Fujiwara’s collection, as well as works by Fujiwara fabricated by Murakami’s staff. And there was merchandise–jeans, tote bags, t-shirts–“which used the paintings as a foundation.”

Except that the paintings themselves are based on something: Murakami’s underlying IP–his characters, visual language, design elements, etc. It’s the same basis which gets translated into products and media from paintings to plush toys to cell phone charms, all at different price points. In the Japanese context, there is no distinction between craft and object and art. It’s a perspective that makes me weigh my own assumptions and motives for making a painting vs a photo vs a print, an edition vs a unique work.

for this image and many more: “Hi & Lo” Curated by Hiroshi Fujiwara and Presented by Takashi Murakami [slamxhype.com]

Hi & Lo Opening [kaikaikiki.co.jp]

What I Thought Of Looking At Today: Tomma Abts

More from Paper Monument, the print version #1, an interesting critique of Tomma Abts’ Turner Prize-winning exhibition in 2006 by editor Dushko Petrovich:

Understatement is of course a wonderful tactic, provided that you first have something to state. Without content, the muted tends toward the silent. If, on the other hand, a painting’s content is the process of painting, then the general feeling drifts toward something worse–a kind of false modesty. It is hard to fault such carefully made, quiet–you could even say flawless–objects, but there is something about their very correctness, about their self-imposed limits, and the absence–or eradication–of risk, that makes their introversion hard to admire.

These paintings have been praised both for looking like early modernist paintings and for not looking like early modernist paintings. I think the trouble stems from the desire to make paintings with no referent. As the vocabulary for this kind of endeavor is inevitably limited (the surface of the painting can’t refer to the surfaces in the world, the color can’t resemble the color in the world, the shapes can’t, et cetera,) a lot of the attempts are going to look like variations: both repeating and not repeating the previous patterns. This brings us back to the screen savers. The lesson seems to be that if you attempt to make a painting with absolutely no referent, this painting will look (a) like previous paintings with no referent and (b) like recently outmoded developments in technology.

But just because it’s impossible doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be done.

The Painting of Triumph [papermonument.com]

Chromatic Modernism Meets Tweeds Catalogue

Oh, Paper Monumentalists, please keep going. The only thing I don’t like about your almost-too-short-to-tweet reviews is that there are too few of them:

Josiah McElheny

“Proposals for a Chromatic Modernism”

September 12 – October 17

Andrea Rosen Gallery

Ruined by a silver-haired power couple (for whom collecting contemporary art obviously constituted foreplay) crowing lustily over the artist’s colored-glass towers while their horrible J.Crew children checked out the Tetsumi Kudo drawings in the back.

[via afc]

Related: “but Mies van der Rohe’s building was a kind of pink.” Modernism: any color as long as it’s white

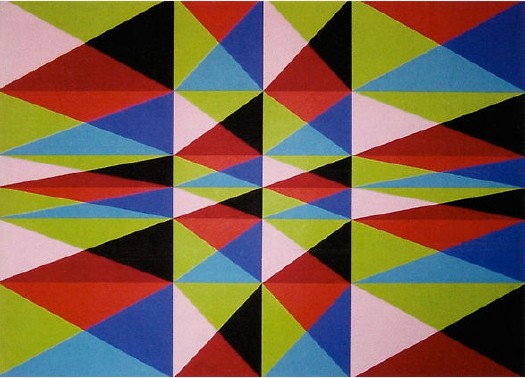

What I Looked At Today – Dean Fleming

You never know what’ll turn up. In the same sale as that Sheeler study is this 1965 geometric abstract painting by Dean Fleming, one of the pioneers of SoHo. In 1962, Fleming founded the Park Place Gallery, an artist co-op, with a small group of other artists, including Mark diSuvero, Frosty Meyers, and Robert Grosvenor. Their first gallery director was John Gibson, and their second was Paula Cooper. Park Place was the first gallery in SoHo [though technically, it was north of Houston on LaGuardia Place], which made it basically the first center of the New York art world that emerged in the 1960s.

By 1966-7, Fleming was feeling burned out on the art scene/market. As he told Michael Fallon in 2005, “In New York I was the ‘parallelogram’ painter, which I thought sucked beyond belief.” Well, I’m sure no one wants to sit around taping paint edges day in and day out to meet the uptown demand [detail below], but it sure looked great while it lasted.

Fleming’s early 1960s abstraction is proto-minimalist, proto-op-art, a bit of East Coast Hard Edge, if there was such a thing, basically resistant to the canonical categories of 1960s New York as we’ve received them.

Last year, Linda Dalrymple Henderson curated a show about the Park Place Gallery artists at UT-Austin’s Blanton Museum. Here’s a quote Sharon Butler pulled when she blogged about the show that kind of brings it all home:

“Park Place artists were united by their multifaceted explorations of space. Their abstract paintings and sculptures, with dynamic geometric forms and color palettes, created optical tension, and were partially inspired by the architecture and energy of urban New York. The group regularly discussed the visionary theories of Buckminster Fuller, Space Age technologies, science fiction, and the psychology of expanded perception, and these ideas become essential to their work. Dean Fleming’s paintings of shifting, contradictory spaces were intended to transform viewers, provoking an expanded consciousness. Di Suvero’s allegiance was to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and his kinetic sculptures explored gravity and momentum in space.

Buckminster Fuller? No wonder the show looks like The Future. It’s like going simultaneously forward and backward in time. [Here’s a smaller slideshow with bigger images than the truly tiny UT-A site. The parallelogram in the background is the second-best Fleming painting in the show; Lime Line, also from 1965, looks like a perfect companion piece to the square Untitled.]

Fleming’s got a shed full of 50 years of work out back of his 40-foot geodesic dome studio at Libre, Colorado, the artists community/commune he co-founded in 1968. I have no idea what his current stuff looks like, but this sweet example from a fascinating, seminal center of activity that’s long overdue for re-examination looks like a steal.

Lot: 67085: Untitled, 1965, Dean Fleming, acrylic on canvas, 32×32 in. est $1,200-1,600 [ha.com]

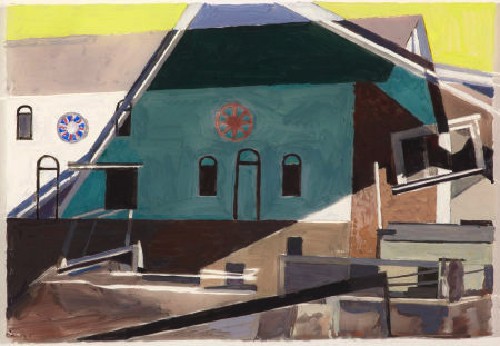

What I Looked At Today – More Charles Sheeler

To be honest, I’ve never felt very interested in the late paintings of Charles Sheeler. After his Precisionist, industrial peak, and his consistently strong, modernist photography, the delicate, highly constructed, cubist/abstract Pennsylvania barn compositions seemed a little twee. They certainly weren’t where the action was in the 40s and 50s, either; that would be Action painting.

But I guess I’ll need to take another look. I kind of like this loose little tempera study for one of his last paintings. Apparently, Sheeler would work out his composition in several preliminary stages; after paper came this one here, tempera on Plexiglass, which seems an odd step. Then came board, and finally canvas.

Maybe it’s nothing great. Maybe it’s just nice to be able to zoom all the way in and see what brushstrokes look like on a glossy, hard surface. Heritage Auction in Dallas certainly wins the prize for best online photodocumentation of its lots.

Lot 66036: Barn Decorations (Hex Signs), 1959, Charles Sheeler, tempera on plexiglass, 6.5 x 9.5 inches [ha.com]

Previously: starting the dutch landscape paintings project

Let Them Eat Ribs!

Wow, I am sorry I missed the opening party for Performa 09 last Friday. A ton of ribs, a ton of honey, a ton of ice, a ton of glasses, a ton of bottles, a ton of peanuts. A ton of ironically gluttonous fun! And by doing it buffet, they save a ton on waitstaff!

Go to 16 Miles of String for the photos, and Claudia La Rocco at Artforum for the writeup.

Now that the Rubells are expanding their practice from collectors, hosts and sponsors to performance artists, the slightest hints of critical engagement with their role, influence, and context might be starting to appear:

“The only thing missing is a giant vat of Purell.”

“‘Mera’s really having her moment,’ one woman commented wryly.”

Baby steps, people!

Related:

Lick and Lather, 1993:

Gnaw, 1992:

Mortar and Pestle, 1999:

whoa, how’s that last image? Big enough for you?

Curate The Controversy?

So now that the White House has returned Alma Thomas’s 1968 painting, Watusi (Hard Edge) to the Hirshhorn amid a flurry of interest in its making and in the artist herself, I assume the museum will quickly put it on public view. Probably with a bit of explanatory text about how and why the aged, arthritic Thomas appropriated her composition from The Snail, one of last works Matisse managed to create before he died.

Maybe they’d even put it alongside some Matisse paintings, which demonstrate the early modernists’ bold innovation of appropriating motifs and forms from African art.

Or maybe they could go all out and borrow The Snail from the Tate, so it could hang alongside Thomas’s painting, allowing a careful examination of what she saw, but also of what she changed.

I’ll be waiting by my inbox for that press release.

Oy. White House Sends Alma Thomas Painting Back To The Hirshhorn

I guess I can understand if the White House saw the rightwing faux-controversy over Alma Thomas’s Watusi (Hard Edge) as an unhelpful distraction, and it’s not like the country elected Obama to be curator-in-chief, but that doesn’t mean their people need to make shit up about it.

Randy Kennedy reported tonight on the NY Times’ ArtBeat blog that the painting has been returned to the Hirshhorn Museum. Watusi is well-known [at least as well-known as a painting by Alma Thomas, an African American woman in DC who only began painting abstraction and exhibiting her work after she retired from teaching, can be] as a deliberate appropriation and alteration of a late cutout painting/collage by Henri Matisse. Some critics of the Obamas ignored this history and strategy and decided the work was plagiarized and that Thomas was either a fraud or a hack.

I read the every comment on the original FreeRepublic.com thread about this controversy, and I wrote that the criticisms were grounded in longstanding conservative views on the primacy of craft and originality in the evaluation of art. In contemporary art terms, the critics of Thomas’s work rejected the pared down abstraction of both her and Matisse [without noticing or caring about the differences in technique: painting vs. collage], and they rejected the validity of appropriation as an artistic strategy [without noticing or caring about the significant differences Thomas introduced]. But it’s now obvious that this controversy is not about Alma Thomas or even about art; it’s about politics.

Which is the only explanation I can think of for why the White House misrepresented the painting’s fate:

Semonti Stephens, the deputy press secretary for Mrs. Obama, said that the painting had been intended to go in the first lady’s office and that the the decision not to put it there was made only because its dimensions did not work in the space in which it was to hang.

“This piece just didn’t fit right in the room,” Ms. Stephens said, adding that the first lady continues to admire the work of Alma Thomas and is happy to have one of her works in the White House. “There’s no other reason,” she said of the other painting. “It really has nothing to do with the work itself.”

As long as you equate “decision not to put it there” with “decision to take it down,” that statement is technically true. But the implication that the painting was not hanging in the First Lady’s office is completely false. It was, and it was there for quite some time. The office is small, and the painting is big, but it certainly seemed to fit fine until a bunch of wingnuts pitched a fit over it.

Off The Wall: White House Drops [i.e., Changes Mind] About Painting [nyt]

Previously: On Wingnuts on Alma Thomas

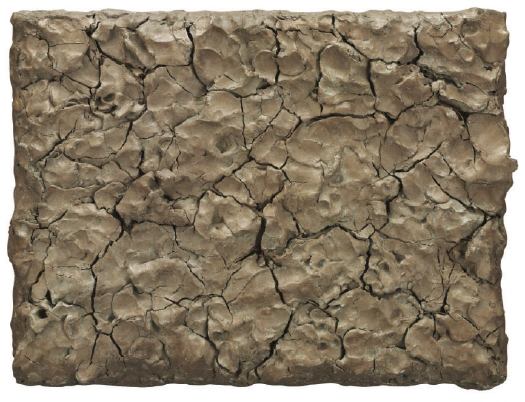

John & Merce’s Bob

Walter Hopps’ 1991 exhibition at The Menil, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, changed my art life, basically. Bob and Cy trekking around Italy. Bob and John and Merce collaborating. Bob and Jasper, whoa. Did not hear much about that at BYU’s Art History Department.

Anyway, Merce Cunningham and John Cage’s art collection is now being sold at Christie’s to support the late choreographer’s foundation. Some of the stuff is fantastic, and some is slightly precious.

Here’s Clay Painting (For John Cage and Merce Cunningham), Rauschenberg’s 1992 recreation/replacement of the seminal 1953 work, Dirt Painting (For John Cage), which the artist borrowed for a retrospective and never returned. He was working on it when Cage passed away in 1992.

Rauschenberg’s original dirt painting was created after his visit to Alberto Burri’s studio in Rome. But while Rauschenberg has acknowledged Burri and his material aesthetic as a central influence on his later Combines, the original dirt painting, with its notion of growing mould defining the form and composition of the work, probably owes more to the influence of a work like Marcel Duchamp’s Dust Breeding of 1920. Duchamp was an important presence behind the creative thinking of both Cage and Rauschenberg who, in 1953, collaborated on a number of projects, most notably perhaps their Automobile Tire Print — a printed drawing made by Cage driving a truck with a painted tire over a series of paper pages laid down by Rauschenberg. In this later dirt painting, Rauschenberg has chosen to use unfired clay as the material for this newer version of his earlier self-defining painting. In this work which, like many of Cage and Rauschenberg’s works is dependent on the passage of time for its resultant form, the cracks that have appeared in the dried clay this time recall more closely the later Cretti paintings made of earth that Burri was to make in the 1970s.

Can you believe Cage driving the car? Automobile Tire Print is like a Zen scroll painting, action painting, a Newman zip, and Pop Art stunt all in one.

Nov. 10, NYC, Lot 5: Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled, 1953-1992, est. $200,000-300,000 [christies.com]

Also: Lot 6: No. 1, 1951, a 50+yr black painting colabo between Rauschenberg and Cage, est. $800,000-1,200,000

Related: Alberto Burri’s Cretto on greg.org

Digital To Analog Paint Matching?

Maybe I’ve just been living in the digital world too long, but I’d like to somehow extract a color list from these polygon-laden Google Map images, and then order paint that matches. Only I’m not finding a vast, well-developed, digital-to-analog paint matching infrastructure in place. Does anyone have any ideas?

Obviously, I can see why no one would want to match colors to a JPEG or PNG; the range, accuracy, and quality of color in the physical world significantly outstrips the digital approximations. And it’s not like there’s a common, systematized language of color that crosses the digital/analog border. Binhex or RGB for paint? Pantone for Photoshop?

I’ve been talking to several painters about this the last few weeks, and they’re all for mixing my own colors, or at least having an artist mix them for me, by hand/eye. And I can respect and understand that. With mediums and grounds and consistencies and undercoats and transparency and absorption, paint turns out to be a vast, complex, multifactored thing, and I’m fascinated by how quickly these conversations of a topic I nominally thought I knew something about leave me in the dust.

But the digital essence of the original seems germane here. Although I suspect the blob in the Noordwijk image above was just cut and pasted there by the obscurer [like the Dept. of Defense HQ clearly was], the camo polygons are usually generated by software, an algorithm that carves up the underlying [sic] digital image and then reduces each component to a dominant or average [sic] color. The data aspect will have to yield to the object at some point, if only when the paint actually hits the printed photograph’s surface. Since the loss of information–or its censorship, or its transformative destruction–is one of the most interesting elements of these images, I’d like to make sure I’m accounting for the changes at each step along the way as best I can.

Collecting Dutch Landscapes

I just got the first prints of Dutch Landscapes to paint. And I’ve captured a few more to prep for printing. Here are a few more of the camo-obscured Dutch sites I also like but haven’t gotten around to capturing and printing yet. Most are military or intelligence installations of some kind, culled from the Onherkbaar/Unrecognized list here:

View Larger Map

The landscape and architecture around this one on the Maas in Rotterdam has a really nice, explicit geometry of its own. The light in some of these is just wonderful, too. So strong and clear. Which is what you’d want, obviously, for aerial photomapping. As Stefan reported on Ogle Earth back in 2006 when this dataset debuted, the fact that these were not satellite images is intrinsic to their camo censorship. Satellite imaging is considered to be beyond Dutch jurisdiction, but permits are required for aerial surveying, and the images are reviewed to censor “vital” military or intelligence buildings and sites.

View Larger Map

More landscape geometry. This one reminds me of Isamu Noguchi’s admiration of hatake, the rice paddy landscape of Japan, a terrain which, like the Netherlands, was the product of centuries of intensive human sculpting and engineering. [That said, I can’t find any mention of the Noguchi quote I’m thinking of.]

View Larger Map

This one’s the Palace Huis ten Bosch, the Queen’s residence. I love that the tennis court and the sculpture garden at the top are not considered “vital” sites. While trying to identify any of the installed works, I learned that H.M. Queen Beatrix is quite a fan and practitioner of sculpture and maintains at studio there at the palace.

‘The Sound of Footsteps’

Tacita Dean on the making of Craneway Event, the rehearsals of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company in a former auto factory on the San Francisco Bay, which she filmed exactly a year ago:

I edited it alone on my film-cutting table using magnetic tape for the sound, which means you have to continually mark everything to keep the film in sync. The sound and image are separate, and the moment you lose sync it’s a nightmare: It’s just the sound of footsteps, which could be from anywhere in the film so it’s nearly impossible to find sync again.

17 hours of film edited down to 1h48, which fits nicely with the “longueur of some of [her] other films.” Looks and sounds fantastic.

Tacita Dean | 500 Words [artforum.com]

Craneway Event premieres Nov. 5-7 at St. Marks Church as part of Performa 09. [performa-arts.org]