Anyone with an interest in Piet Mondrian’s painting technique probably already has Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings, published by the Harvard Art Museums in 2001. It’s a fascinating, in-depth, and not-at-all boring look at a unique body of Mondrian’s work, based on the scholarship of art historian Harry Cooper and forensic painting scientist Ron Spronk.

They examine a group of 17 paintings which Mondrian took with him to New York when he fled Paris just before the outbreak of WWII. Mondrian had already shown some of the paintings, but he reworked them so significantly after his arrival in the US, that he gave them all two dates. [The Phillips Collection’s Painting No. 9, for example is dated 1939-1942.]

Cooper and Spronk get deep into the layers of paint to reveal how Mondrian constructed and executed his paintings, and then how he altered them. It’s great, geeky stuff, and the book is filled with weird, interesting photos of details–like 40x zooms on brushstrokes, and the messy backs and reshaped stretchers–that people who don’t own Mondrians never get to see. And there’s X-ray photos and spectral analysis that you usually only see used on Old Masters, rarely on modern art. These images, these paintings, are objects, after all, and they were made by someone. It’s a basic reality that is somehow easy to forget.

Buy Mondrian: The Transatlantic Paintings for like $40, a third off the $60 cover price [amazon]

Category: art

What I Looked At Today: Theo van Doesburg Edition

It’s hard to see Theo van Doesburg’s work up close these days, especially paintings. But for this Dutch Landscapes paintings project, the technical and theoretical logic of both Mondrian and van Doesburg is pretty inarguable.

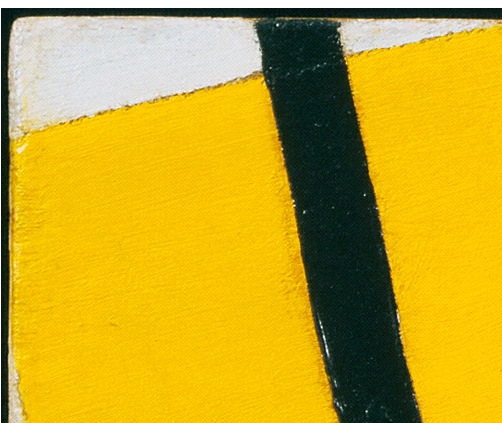

Though the de Stijl folks were pursuing geometric purity and truth, not deploying abstraction as an obscuring, information-smothering blanket, the boundaries of their color planes and lines are interesting reference points.

And fortuitously, a new, expansive exhibition of van Doesburg and his network of influence across the avant-garde, just opened at the Stedelijk Museum De Lakenhal in Leiden. It will travel to the Tate Modern in February. Which is as convenient an occasion as any for the release of a beautiful hi-res image of Simultaneous Counter-Composition, 1929-30, which is on loan from MoMA’s collection. Just look how the yellow brushstrokes come up right against the black line. And the free edge on that little white wedge up there,

The Knew Museum

At the press preview of the New Museum’s Urs Fischer show yesterday, curator Massimiliano Gioni said that Fischer “treats reality as if it were software,” an assessment I suspect is designed to be tweeted more than analyzed.

Gioni and Fischer are entitled to use any metaphor they care to, of course, and this artist-as-reality-coder trope may be borne out nicely in the scholarly catalogue essay. But it also the kind of cross-disciplinary conceptual appropriation that leaves itself open to mockery by people who actually know what they’re talking about, like how NYU physicist Alan Sokal submitted a nonsensical paper, “structured around the silliest quotations [he] could find about mathematics and physics” made by postmodernist academics which questioned the hermeneutics of quantum gravity, to the cultural studies journal Social Text–who published it without question or peer review.

But looking at the work, Gioni’s explanation may turn out to be less deep but more valid than it first seems. The “Labyrinth of Mirrors” on the second floor, for example [above, in a photo from @artnetdotcom], is full of four-sided pictures of objects on mirrored boxes, which distort the space of the room as you walk around them. They feel like real-world approximations the XYZ-grid boxes inhabited by irregularly shaped virtual objects in Google Sketchup or the CAD/CAM programs. Which makes Fischer a user, not a coder.

Spatially, they labyrinth also gives off a bit active camo/invisibility vibe, like James Bond’s Aston Martin in Iceland, or–yes, it seems I have to go there–The Matrix.

So the world we see is just a construct, all ones and zeroes, and we’re too asleep to know it. Or the digital worlds where we increasingly spend our time–Google Earth, Halo, Second Life [oh wait, that’s right, no one actually does Second Life]–are rapidly eating away the physical world’s monopoly on reality, confounding our expectations and perceptions along the way. Maybe it’s all making too much of a throwaway soundbite.

One thing I’m sure of though, is that Rotterdam architect Roeland Otten finished his trompe l’oeil Transformatie project just in time. [via]

Autoprogettazione Updates From All Over

Sheesh, as if I wasn’t painfully aware of the nearly finished Enzo Mari x Ikea Mashup table sitting behind my sofa, I get this, from Peter Nencini, [above] which frankly just hurts:

A couple of weeks ago we reassembled 32 studio tables, originally built last year to Enzo Mari’s Autoprogettazione plans, published in 1974.

I’ll assume that they’re not putting twelve coats of hand-rubbed tung oil on theirs. At least I can hope my next 31 tables will go much more quickly.

Then there’s Wallpaper magazine swooping in with Autoprogettazione Revisted at the Architecture Association in London, where AA students and a few name designers show off their Mari-inspired hacks, and there’s even a lecture by Mari himself, which is alternately animated and tedious, and thanks to the on-the-fly translation, twice as long as it would normally be.

But even as I worry a bit about missing a trend–or worse, finding myself caught up in one–I’m reading the AA’s catalogue and instructions for the show–because yeah, I’d totally make Kueng-Caputo’s awesome lamp, wouldn’t you?–and I find this:

Mari was ultimately disappointed with the original response to Autoprogettazione, believing that ‘only a very few 1 or 2% understood the meaning of the experiment’…Enzo Mari hoped that the idea of Autoprogattazione would last into the future. Autoprogettazione Revisited reveals that it has done just that. Not all of the artist/designer responses in Autoprogettazione Revisited can be duplicated by the enthusiast, but they are inspirational and without a doubt follow the Mari principle that ‘by thinking with your own hands, by [making] our own thoughts you make them clearer.’

I’ve always understood Mari’s project to be a critique of the self-important distinction between the “artist/designer” and the “enthusiast.” In his lecture, Mari actually said that of the many thousands of requests for Autoprogettazione plans, only 1-2% of them were from design professionals. I can totally imagine the head of an architecture school gallery thinking that those two tiny, so-enlightened populations are the same, but I’m not at all sure Mari would agree with her. [thanks andy for the links]

Korean Art Flipper Eats It On Schnabel Dog

It happens all the time in the Old Masters market, but I could never understand how a work of art could sell at auction for one price, only to reappear–and to sell–at a fair a few months later with a vastly inflated price tag. I mean, I can imagine how a dealer would do it; and if there were a cleaning, a restoration, a different presentation, or even new research or a new attribution, it can even make sense. What I don’t get is the mindset of the collector who, either through indifference or ignorance, buys a work that just sold very publicly for 40-80% less than what he paid.

Of course, it would explain a lot if these chumps are all North Korean 80’s art speculators. Let’s pick at some of the confusing details from the New York Law Journal’s error-ridden story of an unsuccessful lawsuit by one such “collector,” Najung Seung, who the NYLJ describes as “a resident of North Korea” and “a woman who worked in art galleries in Beijing.”

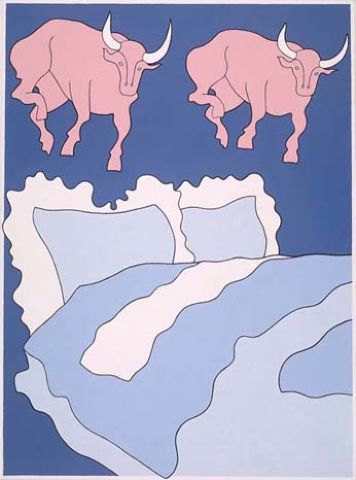

In May 2006, Seung, and who is actually listed in court filings as Korean, not North Korean, bought a 1986 John Wesley painting for $118,000 from Dinaburg Arts, a NY art advisory. Its principal, Mary Dinaburg, had just curated Wesley into the windows of the Hermes store, and Seung was friends with one of Dinaburg’s assistants.

But despite holding a paid invoice for Bulls and Bed, “the following March [i.e., 2007], Seung learned that Dinaburg had sold the Wesley painting to another buyer,” reportedly for $200,000. Way to stay on top of things, Najung. [Bulls and Bed was at Basel this past summer, btw, offered by Wesley’s London representative, Waddington Galleries, for $300,000. It’s still available.]

To make up for it, Dinaburg apparently offered Seung a $200,000 credit toward the purchase of Chinkzee a giant, truly execrable, 1983 velvet painting of a dog by Julian Schnabel. It was a $500,000 painting, Dinaburg said, though she’d let it go at the “gallery net” price of $380,000. In a May 2008 email, Dinaburg wrote, “I believe we have a good opportunity to place your work within the year and resell it a profit.”

Instead of her main firm, though, Dinaburg offered the Schnabel through Fortune Cookie Projects, [not Ventures, NYLJ. Who’s proofing these things?], the Asia-focused art advisory operation she’d launched in 2006 with Howard Rutkowski, who oversaw Asian, modern, and contemporary art for Bonham’s auction house in London.

Seung agreed and paid Fortune Cookie an additional $90,000 in June 2008. Her lawsuit mentions a final invoice [presumably unpaid] for the last $90,000 installment, dated October 30, 2008, aka The End of The Art World As We Knew It.

At some point–even though it kind of matters, it’s not clear when–Seung realized that Chinkzee had sold in May 2007 at Phillips in New York for $156,000, well above its original estimate of $60-80,000, but well below the $500,000 value she’d been told. [How Seung managed to avoid getting those gigantic catalogues Fedexed to her, I have no idea; Phillips was blanketing the globe with those things.]

Anyway, if Seung’s case is meaningful, it’s only as a reminder to collectors to do their own damn homework; the NY Supreme Court determined that art advisors and even dealers are not “experts,” and their opinions are just sales patter which constitutes, at best, “non-actionable ‘puffery’…on which a sophisticated commercial entity could not reasonably rely.”

When I started writing this post, I thought it was just a savvy dealer using the promise of an easy follow-on flip to flip her own auction purchase to a clueless, foreign speculator. But there’s someone else involved. Dinaburg’s emails to Seung, including the one promising “the gallery net,” make it sound like Chinkzee was coming from the artist himself:

(1) We are working with the very well respected [sic] and important [sic] artist Julian Schnabel. I was thinking that I could offer you what I offer the galleries directly…

(3) I have spoken to the Schnabel studio and have gotten the final lowest possible price on both [?] works

(4) I was over there with Julian before I went to Hong Kong and we were pricing work and you will never see a Schnabel form [from] the studio coming out at the prices they are now, but higher.

Did Schnabel buy his own old painting back from Phillips, and then flip them back through Fortune Cookie? Or was Chinkzee just part of Fortune Cookie’s big, 2007 All-Asia Tour of Schnabel’s “best works”? [A: Yes.] There is a punchline here somewhere about sarong-wearing white devils peddling Chinkzees out of the back of a Fortune Cookie van as they drive across China, but I can’t figure it out.

No Money Back for Gallery Worker Who Relied on Estimate of Schnabel Painting’s Value [law.com]

Sept. 2007: Julian Schnabel Presents Best Works in Beijing [china.org.cn]

100-ft Spheres In The Center? On Buckminster Fuller’s Original Expo 67 Pavilion

From the Other Things I Didn’t Know About What Goes Inside Geodesic Dome Pavilions Department:

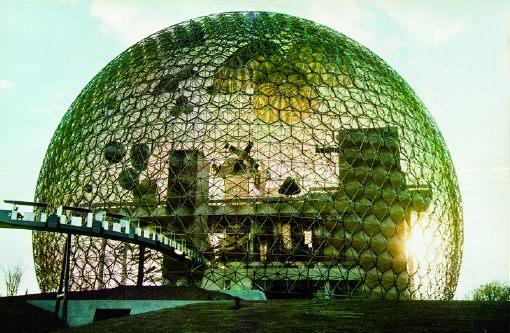

Christine Macy and Sarah Bonnemaison devote a chapter in their 2003 book, Architecture and nature: creating the American landscape to geodesic domes, including this description of Buckminster Fuller’s original vision for the US Pavilion at Montreal’s World Expo 67:

His [Fuller’s] design of 1964 featured a dome nearly twice the size [of the 250-ft diameter, 3/4 dome by Fuller and Shoji Sadao that was realized] with a massive interior gallery. From this elevated vantage point, the viewer would focuse their attention inward to a hundred foot diameter Earth tranforming slowly into an icosahedron, before it opens up, unfolding like a flower as it descends to the floor. [what a sentence. -ed.] In this way, Fuller’s “geodesic” globe transforms into his “Dymaxion” map of the Earth before the visitors’ eyes, displaying the “one world island in one world ocean.” And then it would come to life. Wired with tens of thousands of miniature light bulbs, this great map would begin to pulsate with patterns–showing world resources, electricity generation, the flow of transportation and communication systems across the Earth. This interactive display, this giant bio-feedback device, would be the playing surface of the “World Game.” Assembling in teams or playing by themselves, visitors were intended to chart out optimal paths to link resources with industries and population centers, to streamline transportation flows and maximize satellite coverage The aim, according to Fuller, was to “make the world work successfully for all of humanity…without anyone gaining advantage at the expense of another.”

Since he had not actually been asked to design the exhibit, just the pavilion, this idea was rejected and replaced by a selection of quilts, duck decoys, and Cary Grand billboards.

American Painting Now Then

How to account for my dogged fascination with the temporary/permanent, futuristic/historic paradoxes of Expo art and architecture?

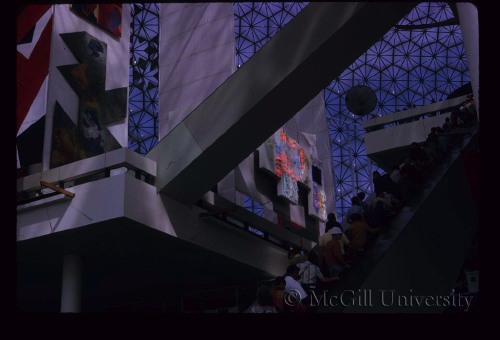

Buckminster Fuller’s 20-story Biosphere was far and away his greatest single success and the hit of the most successful modernist world’s fair, the Expo 67 in Montreal. And yet how little did I consider what was in it: a giant exhibit of the movies; The American Spirit, an exhibit of NASA satellites and space capsules; some crafts or whatever, and American Painting Now, 23 huge paintings commissioned by Alan Solomon from a “Who’s Who of modern art,” including :

James Rosenquist, Claes Oldenburg, Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Jim Dine, Ellsworth Kelly, Barnett Newman, Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein. Their works illustrated trends such as abstract expressionism, op, pop, hardedge and geometric art. Like the space component, this part of the American exhibition was truly spectacular. The works, gigantic, simple and colourful, paid a vibrant tribute to the creative vitality of artists who now count among the great masters of 20th century painting.

Uh, and from Fuller, too, from the looks of that giant Dymaxion Map right there.

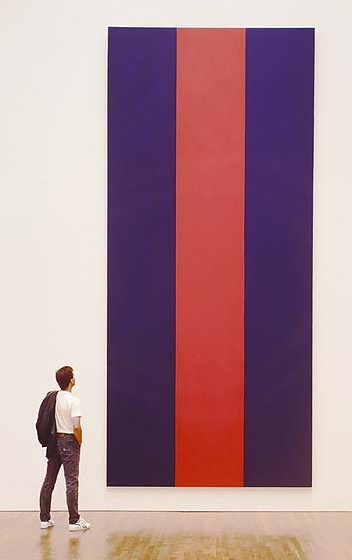

From a 1996 book on Voice of Fire, Barnett Newman’s own 17-foot tall contribution, we learn Solomon requested that the artists [all male?] “contribute paintings that are (a) large in scale and (b) vertical in format.”

I want to quote “Exorcism in Montreal,” the April 30, 1967 review by NY Times critic and famous Newman nemesis John Canaday, in its entirety, but I won’t:

I want to quote “Exorcism in Montreal,” the April 30, 1967 review by NY Times critic and famous Newman nemesis John Canaday, in its entirety, but I won’t:

Here we have the same old clique of names that have been handed the favors regularly in Venice and everywhere else on the circuit. A natural response to the list is “Oh, no, not again!” There is that tiresome Barnett Newman, who this time turns out three vertical stripes in two colors–but they are 17 feet high. There’s Jim Dine, with nothing but two big slabs of enameled canvas, in two flat colors, bearing in one corner a notation as to the brand of paint used–and the panels are 35 feet high. There is Roy Lichtenstein being Roy Lichtenstein again, but now 29 feet high.

There are all the rest of the club, not including some whose work was not fully installed on press day, and some whose work seems to me to have more substance than the ones listed, for instance James Rosenquist’s colossal “Firepole.” I have chosen the most vacuous because in this setting even they are part of a genuinely spectacular show fulfilling demands that could not have been met by any other kind of painting.

The dimensions given above tell that the paintings, most of them done for this spot (what other spot could hold them?), are gargantuan…they are played against strips of sail cloth in heights up to that of a 10-story building. It is as if the whole water-treading esthetic that they represent had been originated and sustained by some genii who knew that one day a form of painting bold enough and shallow enough to supply enormous bright banners for this pavilion would be necessary.

And then there’s Canaday’s assessment of the NASA artifacts, which basically hits it home for me with the art/science beauty paradox:

…since technology is creating the most beautiful objects today, and the most imaginative ones, Apollo might also be thought to have added one more muse to the group that he has always chaperoned.

Of course, there is no separating the fascination of the Apollo Command Module as a scientific object from its quality as an esthetic one, with its self-generated form and its patina burnt into it during the minutes of its descent rather than by centuries of weather, but it is a beautiful object all the same–inherently beautiful, and no other word than beautiful will do–as well as an historical monument with emotive associations And that is what great works of art used to be.

Ah, so it’s just the domes and the satelloons.

Update: From Architecture & Nature (2003), more details/corrections on who showed what: Kelly had a 30′ canvas, no title given. Robert Indiana, Cardinal Numbers. At just 13’x15′, Robert Motherwell’s Big Painting #2 was anything but. Lichtenstein: Big Modern Painting [sensing a theme here?] Helen Frankenthaler was The Woman Painter. And the Dymaxion Map was by Johns, “a small [sic] token to his friend Fuller’s desire to have the map be the centerpiece of the pavilion.”

Interior images of Biosphere, the US Pavilion at Expo 67 from The Dixon Slide Collection at McGill University. [mcgill.ca]

Q: was this the Ellsworth Kelly? [no, see update above]

Previously: Hmm. That satelloon & command module show was so good, they used it again at Expo 70 in Osaka.

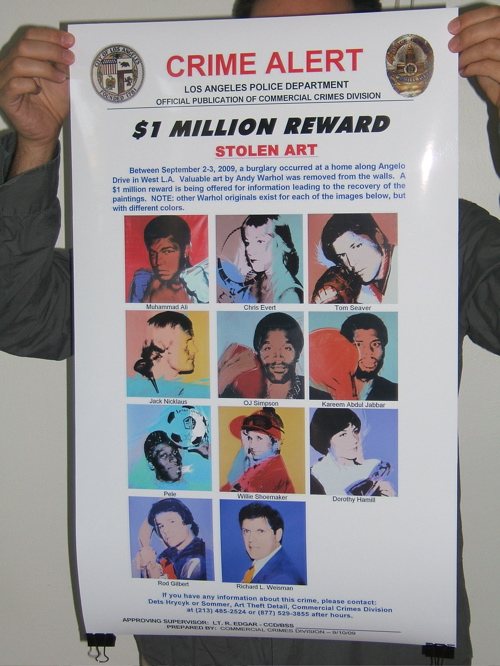

Don’t Find The Warhols Yet, Anyway

So it looks like we won’t be finding the Warhols just yet. The Kickstarter project deadline came today, and only $265 of the $1400 or so required to print and ship a batch of giant Wanted posters had been pledged. A huge thanks to all the folks who pledged, though; it was and is very encouraging.

This doesn’t mean there won’t be giant Wanted posters; because frankly, they’d look awesome, and seeing them is at least half the point of the project. The project had to tread a fine, meandering line through that poster awesomeness on the one hand, the unofficial, unsanctioned publishing of the LAPD’s poster on the other, and–wait, how many hands do I get?–the obvious intellectual property issues. And of course, underpinning the entire thing is the obvious challenge it poses to our sympathies and sense of value: is it harder or more problematic to feel altruistic and volunteerish towards someone who’s lost 11 of his 80-plus Warhol paintings? Is the world actually a worse place because one of eight sets of these portraits is now missing? Did the answers to these questions change after the insurance company’s reward was rescinded and Weisman started trashtalking the investigators?

My own interests and motives–to realize and propagate these giant Warhol posters in various back rooms and offices of the art world–still depend on this presumption of a community chipping in and keeping an eye out to help find these missing artworks. It’s acting as if the art world is a small subdivision, where everyone joins the search to find the lost puppy. If there’s a more hilariously inapt metaphor for the art world than that, I guess I don’t know what it is.

Holden Caulfield, Curator

From the Observer profile of Massimiliano Gioni:

Growing up outside Milan in a town he likened to Newark, Mr. Gioni found himself drawn to art precisely because there were no adults talking to him about it. “It didn’t belong to the school or the teachers,” he said. “It was mine.”

When he was 14, he started reading the Futurists and the Dadaists–he can still recite by heart Tristan Tzara’s Manifesto of Mister Antipyrine–and listening to Sonic Youth, Fugazi, and Dinosaur Jr. He also started looking at the pictures in Artforum and Flash Art, and loving what he saw “because it was so strange.”

And from Stranger art critic Jen Graves’ review of “Parenthesis,” a new show at Western Bridge in Seattle:

But when I first read Tristan Tzara’s 1918 Dada manifesto in college, as a kid still angry over my parents’ messy divorce and the messy new relationships that followed, I was moved by Tzara’s childlike claim that “every product of disgust that is capable of becoming a negation of the family is dada.” If the family, like art, could not be a strong, safe nest, then it had to be abolished; it’s less painful to do away with families than to watch them fail. (Dada was always from the perspective of a disillusioned child.)

Either we’re in a neo-Dadaist moment right now, or Tzara’s Manifestos are the Catcher in the Rye of the art world. [via jason]

The Quality Of A Skillfully Executed LeWitt

Yale just held a panel discussion on conservation and artist intention. This kind of thing drives me a little crazy:

Not all work inevitably degrades, though. Some art improves with careful conservation. [Yale University Art Gallery director Jack] Reynolds showed a video of the installation of the massive Sol LeWitt wall drawing show at MASS MoCA. As the audience watched a team wearing paint masks carefully sand a wall, he recalled conditions in Paula Copper’s SoHo gallery in 1968, where the artist completed his first wall drawing. “That wall was anything but smooth, unpockmarked, and perfectly sanded,” he said. Reynolds also noted that many of LeWitt’s draftsmen have specialized in particular techniques, becoming “samurai warriors” in their crafts. A LeWitt skillfully executed today dwarfs the quality of what the artist himself regularly produced. [emphasis added]

Really? I mean, really? I guess if that’s the way it is, then that’s the way it is. But I have to wonder about the implications of this samurai model for the conceptual essence of LeWitt’s work. Here’s how Holland Cotter described the wall drawings process in his review of Mass MOCA, which was organized with Yale:

It also stays resolutely impersonal, never sticking for long with any single graphic style, never showcasing a distinctive touch, never carrying a signature.

Although LeWitt came up with the initial designs, his relationship to the work was otherwise hands-off. He wrote instructions for how the work should be done — firm but easy-to-follow recipes with occasional sweeten-to-taste allowances — but hired other artists to do it. Some he trained, with the expectation that they would train others, who would in turn train still others, stretching on through generations.

So it’s an impersonal priesthood?

For a long time–since the 2000 rerospective at SFMOMA, actually, I’ve had a secret guerrilla LeWitt show planned in my head, where all the wall drawings are executed by civilians. Just take a catalogue with a bunch of instructions listed in it, and start doing them on the walls. I don’t know what that would look like, but for that reason alone, I’m interested to see it.

update: Andrew Russeth, who wrote the original ArtInfo article, just emailed in to claim the “skillful” and “quality” lingo, though I still think he captured the larger point accurately, which is the professionalization and upgraded production values of LeWitt’s wall drawings. [Which may be apt for some, especially later bodies of work like the fresco-like geometric shape murals of the 80’s and the high-gloss monochromes of the 90’s, which were, of course, created in the professionalized era.]

Andrew also mentioned that Dia:Beacon has had a “civilian” LeWitt drawing activity as part of their education program for visiting school groups:

A particular favorite (and one of the most unwieldy titled) with the younger kids was: “3. Wall Drawing #123: Copied lines. The first drafter draws a not straight vertical line as long as possible. The second drafter draws a line next to the first one, trying to copy it. The third drafter does the same, as do as many drafters as possible. Then the first drafter, followed by the others, copies the last line drawn until both ends of the wall are reached. 1972”

Which is great to hear, though I’d be more impressed to hear that they put the resulting drawing on public view. Here is Holland Cotter again on the Mass MOCA LeWitts:

Many of his drawings were done by supervised groups of art students — those at Mass MoCA included — in a learning-on-the-job tradition very similar to Renaissance workshop practice. A master artist provides the overarching concept; senior artists oversee production; apprentices do the grunt work and in the process discover and develop ideas of their own.

So LeWitt’s Conceptual Art construct is really just a return to guilds and craft.

The Best of Intentions [artinfo via 16miles]

It’s So Hard To Get Good Help Finding The Warhols These Days

Yeah, well it’s like five days until the Find The Warhols! project expires on Kickstarter, and we’re still a ways to go from our goal. Normally this would right about the time that a groundswell of sympathy for the victim kicks in, and everyone grabs a couple of posters and hits the streets of Bel Air, trying to find those damn Warhols and bring them home before the storm hits.

A groundswell which might be dampened somewhat by the collector unloading on the LAPD to the LA Times:

Richard L. Weisman, the noted art collector who made news recently when he decided to forgo a multimillion-dollar insurance policy for stolen art, had some critical words for the LAPD detectives investigating his case.

“Maybe if they would do their job … and spent some time looking for the art instead of being accusatory of the person who had it stolen, they might actually find it,” Weisman said in an interview last weekend.

Weisman then tiptoed into Pebble Beach Pollock territory with this denial of any involvement in the paintings’ disappearance: “The idea that I would steal from myself is the most ridiculous thing I’ve ever heard.”

So then you haven’t heard about the attempt to crowdsource 500 giant copies of the LAPD’s awesome Warhols wanted posters?

Collector who reported Warhol paintings stolen has tough words for LAPD [latimes]

Original = Higher Resolution

Lawrence Weschler narrates a slideshow of David Hockney’s iPhone/Brushes drawings for the NY Review of Books:

Lawrence Weschler narrates a slideshow of David Hockney’s iPhone/Brushes drawings for the NY Review of Books:

When he finishes one of these drawings, he sends it out into the world…

There’s about 15, 20 people, and he assumes that we send them on to other people if we like it.

One of the things that’s quite fascinating in this whole thing is that we have the original on our iPhone. Which is to say there’s no version that’s higher resolution than the one we have; we all have the same resolution. The ones you’re looking at right now are originals as well.

Technically, there are images and .brushes files. If you send Brushes images as .brushes files, their creation can be replayed like an animated movie. [It makes me interested to try to animate a Brushes work the way, say, William Kentridge does, treating the buildup of strokes as a narrative device. But that’s not the point right now.] But if Hockney just sends out images, then his friends have a file that is distinct and different from the “original,” and all its embedded generative data. It is certainly different from the image embedded in a slideshow.

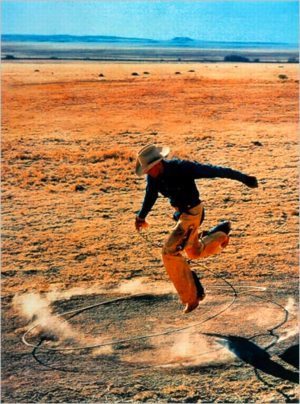

But that’s a highly particular assumption of originality that pertains to this app. Weschler’s assumption that a copy is lower-resolution than an original has much broader implications. It’s an assumption that’s hardcoded into almost all our image reproduction technology, as I inadvertently discovered when I began trying to accurately reproduce the 300×404 pixels of 300×404, after Untitled (Cowboy) 2003 by Richard Prince, the original of which is a .jpg file.

An image invisibly but irrevocably sheds a phenomenal amount of data and time- and process-related content when it goes from .brushes file to .png or jpg. In precisely the opposite way, transferring 300×404 to anything other than the jpg it is turns out to involve the addition of an incredible amount of data, via interpolation, upgrading and smoothing and blending algorithms. Those original 121,200 pixels get drowned out completely.

Audio Slide Show: Lawrence Weschler on David Hockney’s iPhone Passion [nybooks]

Previously: 300×404: The making of

Norton Family Christmas Project At The MoMA Store

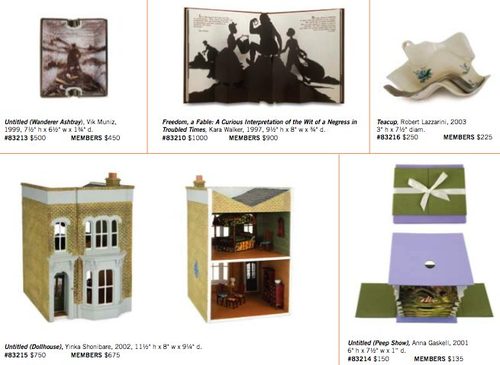

Wow. Every Christmas since 1988, Peter Norton and his family have commissioned artists to create a work, which they produced and sent out to friends, family and other art world folks. Now Norton, a MoMA trustee, is emptying out the closet and donating all the extra pieces for sale, with proceeds set to benefit PS1 [Norton was the Chairman of PS1 until just recently. I’ve helped do fundraising for both MoMA and PS1 for more than 15 years now.]

Anyway, the works are priced from just $45 for the 1990 gift, a CD by Richard Kostelanetz, to $675 [$750 for MoMA non-members] for the 2002 and 2005 gifts, an awesome doll house by Yinka Shonibare and an awesome music box by Christian Marclay, respectively, to $900/$1000 for 1997, Kara Walker’s classic silhouette pop-up book. If there’s a bargain in the bunch, it’s probably 2004, a beautiful glass bowl with molded handprints in the bottom by Do Ho Suh, which is just $225/$250. It’s a very MoMA-y, Christmas-y, and well executed gesture.

There are seven other editions, including the very awesome 1998, a blanket by Jim Hodges, that are only available if you buy the “complete set” for $5580/$6200. The quotation marks around “complete set” probably refer to the absence of the 2000 gift, a Mr Pointy figurine by Takashi Murakami, and the 2007 gift, a pair of tricky salt and pepper shakers by Nina Katchadourian.

So whether you’re filling in your collection for the years you were on the outs with the Nortons or you want to give a little something back after so many years of getting art free and unbidden in the mail, it’s a pretty sweet deal.

The Peter Norton Family Christmas Art Projects editions will go on sale October 28 at 9AM at MoMAstore.org/Norton [momastore.org]

First The Good News: Helio Oiticica Heirs Say Not Everything Burned After All

Note to self, the Brazilian media & world’s wire services: the guy standing outside his burning house and saying he lost everything does not, in fact, know that everything is lost.

Such is the case with the Projecto Helio Oiticica, where the artists’ heirs–his younger brother Cesar and his nephew Cesinha, mostly–have been able to find work that was unharmed in the fire and work that just suffered smoke damage or is otherwise restorable. As Cesinha told the Agencia Estado news service, “When you look at all black, it looks like it’s over, but when we opened the boxes scorched, we thinking works. Improved enough yesterday for today (Saturday to Sunday).”

Among the works found already: many of the Metaesquemas series, up to 350 color experiments in gouache on paper or cardboard from 1957-58. At least two bolides monochrome painted objects are intact, and more only need the glass replaced. several big installations are stored downtown at the Centro Municipal Hélio Oiticica. Two of the artist’s iconic Parangolés, wearable samba painting/banners, which were all thought to be lost, ” were saved by being in an exhibition in Belgium.”

Yeah, so those didn’t burn up, obviously. So at this point, there’s a bit of taking stock, trying to stay positive, a bit of walking back the early over-emotional reactions–and a bit of defensiveness and fingerpointing.

In another Agencia Estado report, Rio’s Secretary of Culture Jandira Feghali criticized Cesinha Oiticica directly for the loss of the works: “In my opinion, we lost a collection by a closed attitude of the heir, in particular.” She charged Cesinha with pocketing the $US20K/mo the city had been paying the PHO to maintain and conserve the collection, a contract which Rio’s new mayor had not renewed.

As Brazilian culture officials deal with the loss of so many works by the country’s most important contemporary artist–one whose recent critical reappraisal has mirrored Brazil’s own increasing prominence on the global stage–issues of private property and cultural patrimony are coming into play:

According to the secretary, lack a regulatory framework in the country to give better conditions to the giving public access and care for works of dead artists. For current law, works are private property of the heirs of artists and their use requires the permission of them.

“My regret is profound, because we tried it any other way. I personally talked to his nephew for us to have the transfer of collection to the Center Hélio Oiticica, for lending. We do not have budget to buy $ 200 million [the estimated value of Oiticica’s estate]. They could not give the entire collection, but a part. There must be a new way to deal with it and there is a law,” said the secretary.

So even after the smoke clears, there’ll still be a heated battle over control of Oiticica’s work.

Fire Destroys ‘90%’ Of Helio Oiticica’s Work

Unbelievable. The Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica refused to sell his work; his estate, the Projecto Helio Oiticica, held an estimated 95% of his entire output when he died in 1980. The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston had a truly spectacular, history-shaking show of Oiticica’s work in 2007, which traveled to the Tate. Roberta Smith said in the Times,

This show is like a large stone dropped into the calm waters of European-American art history. With its thick, lavishly illustrated catalog, it presents an enormously productive artist, writer and thinker whose work effortlessly spans the gap between Modern and Postmodern, Minimal and Post-Minimal. Reflecting inspirations from Mondrian to the samba music of Rio de Janeiro’s favelas (slums), it also bridges first- and third-world cultures in a way that has seldom been equaled.

Now O Globo reports [via artforum] that a fire in Oiticica’s brother’s house has destroyed “an estimated 90%” of the PHO’s holdings. Some installations and conceptual projects designed to be recreated are fine, of course, but his paintings and sculptures, including his incredible bolides [above], minimalist experiments in experiential color from the early 60s that remind me of Anne Truitt’s genre-breaking works, are gone.

Apparently, PHO–which is controlled by the artist’s two younger brothers–was in an ongoing dispute with the municipality of Rio over the government’s inadequate storage conditions and late exhibition payments for the work. As a result, PHO removed the work to the house–where it just burned up. This just tears me up inside to think about it.

A multi-year digitization project for Oiticica’s work and prodigious archives was nearly complete, though, and presumably the 7-volume catalogue raisonne will keep the artist’s seminal ideas in circulation. Without the works themselves, though, Oiticica could end up a digital ghost, haunting artists and art historians of the future.

update: O Globo has photos of the aftermath. The loss may be closer to 75%.

The exhibition catalogue for the MFAH show: Hélio Oiticica: The Body of Color [amazon]