My Twitter feed is so complicated right now.

Category: making movies

Exodus, 1997, Steve McQueen

One of my absolute favorite Steve McQueen films is one of the first ones I saw, a one-minute super-8 called Exodus.

But until now, I’d never heard the making of story of this found scene. According to Carol Kino’s profile of the artist last winter, McQueen became interested in film at Goldsmith’s:

On the advice of a teacher he took to carrying around a Super 8 camera. But because film was so expensive, he rarely used it; he only shot a single, three-minute piece, part of which showed two black men carrying potted palms along a crowded East London street.

The Times incorrectly dates the piece to 2007, but it was included in McQueen’s first US show at Marian Goodman in 1997.

Just a beautiful piece of seeing.

Haven’t Found Tacita Dean’s Sound Mirrors Yet

Maybe it was me looking for Tacita Dean’s Sound Mirrors that brought me there, but David Williams’ 2009 post at Skywritings about Dean, Derek Jarman, Dungeness, gardens, Tehching Hsieh is pretty wonderful:

Everything here has been found, salvaged, re-cycled from this sea-edge place, and is both displaced and quite at home. A manifest testament to qualities of patience, economy, playful invention and a quiet contemplative thusness. For the garden stages a deep acceptance of being here in all modesty and attentiveness. Taking time to make space. Slow time, still moves. A bricoleur Picasso meets the Zen garden.

Jarman bought the house in 1986 for £750; he was scouting for bluebells with Tilda Swinton and Keith Collins for a film shoot. He called it his ‘paradise at the fifth quarter’, a place where he could walk in the ‘Gethsemane and Eden’ of his garden and ‘hold the hands of dead friends’ (Garden).

(Once, when my mother was very ill in hospital, she told me that her mother had just visited her, what a shame I’d missed her. She had knocked on the window, told her that she should ‘come out into the garden’, it was good out there, and it was time. Her mother had died more than ten years beforehand).

Still looking for that Sound Mirrors piece. I suppose I should just go to the gallery.

In fact, skywritings is good all over. [sky-writings.blogspot.com]

I’m An IBMer’s Son

Rather sensibly, IBM tapped Errol Morris to create films commemorating the company’s 100th anniversary. Even when a guy delivers slightly underwhelming lines like, “We changed the way the world shops,” this one, They Were There, is pretty awesome.

My dad worked for IBM for decades, long enough for me to have a bias for white dress shirts ingrained into my psyche. And I did interview Errol Morris that one time.

And while I can understand why it’s not in there, I do kind of wish the company would, when celebrating its history, acknowledge the longstanding, critical role IBM, its technology, and its German subsidiary played in the Holocaust. Because they were there. And that’s certainly more important than changing the way the world shops.

IBM Centennial Film: They Were There – People who changed the way the world works [youtube via daringfireball]

At The Movies With Mao Zedong

Tom Scocca posted about the story just before Christmas, but apparently, Mao Zedong was a Bruce Lee fan.

That’s how the Chinese press is reporting the story of Liu Qingtang, [刘庆棠], a ballet dancer and close ally of Mao’s wife Jiang Qing, who, as the deputy minister, was put in charge of films at the Ministry of Culture.

Mao was encouraged because of cataracts to cut down on his reading, and to switch to film. Liu was charged with programming and procuring prints for Mao’s private screenings.

Scocca picked the story up from Raymond Zhou in China Daily, but Liu’s account was first published in November in the Yangcheng Evening News, a major daily out of Guangzhou. It was posted online a few weeks later. Here’s the Chinese, “毛泽东有多迷李小龙?”, and a choppy Google translation, “Mao Was a Bruce Lee Fan?” [It’s remarkable how far Chinese-English autotranslation still has to go. We’re barely at Babelfish levels here.]

Liu says his story is from 1974:

Mao Zedong’s like to watch movies there are several categories: first, the international award-winning film; second film biography, “Abraham Lincoln”, “Napoleon,” he loves; third is like watching garden scenery film, like most British films. Often, Mao heard good movie, the file will be down to watch, watch movies right away, very happy.

. At some point, then, Liu traveled to Guangzhou, and on to Hong Kong, where he had not a little bit of trouble getting prints of Lee’s films, The Big Boss, Fist of Fury and The Way of the Dragon, from the wary movie mogul Sir Run Run Shaw.

Where Mao would watch only a few minutes at a time, taking up to ten days to finish another film, he apparently sat straight through Lee’s movies, and even demanded repeat viewings. Liu was afraid to send the prints back to HK, in case Mao asked to see them again.

The incorporation of Mao into the Bruce Lee fan club, the American-born, Hong Kong-raised, one-quarter German Lee [who is known by his given Cantonese name, Li Jun-fan (李振藩)] was timed with the premiere on CCTV6 of a documentary, “Legend of Bruce Lee,” which debuted at Beijing University. It all serves to retroactively position Lee as an inspiring, nationalistic hero of all Chinese, including the Mainland, where he was unknown during his lifetime.

And it all makes me wonder what was actually going on film-wise in the PRC during the tumultuous waning days of Mao’s rule. Because there are some contradictions and gaps in Liu’s story as it’s reported:

Wikipedia, which has the only actual date I can find so far, says Liu was installed as Deputy Culture Minister in February 1976.

Jonathan Clements’ 2006 biography of Mao dates the cataracts to 1974, but also says that Mao was nearly blind, and his slurred speech could only be decoded by his nurse.

As Reeve Wong pointed out to China Daily, Bruce Lee’s films were actually produced by Shaw’s rival studio, Golden Harvest. It’s not clear how or where, but Liu still insists that he got the prints from Shaw.

Given the difficulty in tracking down prints of Hong Kong’s most popular films, I have to wonder what “international award-winning films” and biopics Liu was able to get his hands on. I mean, was there a copy of John Ford’s 1939 film Young Mister Lincoln laying around a cinema after the Revolution?

And the big question, did he watch Michelangelo Antonioni’s epic 1972 documentary Chung Kuo? Antonioni originally shot Chung Kuo/ Cina as a left-to-left cultural gift, with Communist Party participation and supervision. After it came out, though, Madame Mao & her cinematic comrades denounced spectacularly as a capitalist reactionary insult to the Motherland.

A lengthy bio of Liu Qingtang at hudong.com says that in 1976 as the Gang of Four maneuvered for post-Mao power, Minister Liu personally oversaw the production of three “hit films,” Back [反击]、Grand Festival, [盛大的节日], and Fight [搏斗] which attacked Deng Xiaopeng.

After Deng regained and consolidated power and began undoing the effects of the Cultural Revolution, Liu followed the Gang of Four into public disgrace, trial and jail. But he’s apparently out now, and doing fine, if not quite keeping his dates and titles straight.

Photo-Murals, By Julien Levy, 1932

You know what, I could try and just quote the awesome parts, or hold up for scrutiny or amusement the seemingly unquestioned assumptions about art, painting photography, and decoration that inform it.

But instead, I have just typed in all of Julien Levy’s catalogue essay on photomurals from the Museum of Modern Art’s 1932 exhibition, “Murals by American Painters and Photographers.” It’s after the jump.

Levy was a pioneering photography dealer who was brought in by Lincoln Kirstein to curate what would be the Modern’s first exhibition of photography. It’s really hard to overstate the importance of Levy’s role in the history of art and photography. He saved, with Berenice Abbott, Atget’s photos. He gave first shows in the US to Brassai, Cartier-Bresson, Moholy-Nagy. [He organized the US premiere of Moholy-Nagy’s short film work, Lichtspiel in 1932 which, really? Because it barely premiered in Berlin in November 1932. That’s hardcore.] He had the first surrealism show in the US. He promoted the found and anonymous photograph as readily as the known artist’s work. And though he barely sold any actual photos in the 17-year life of his gallery, he was a remarkable and prescient advocate for the medium as art.

In 2006, the Philadelphia Museum staged an incredible exhibition of photos and material from Levy’s archive, which they’d acquired from his widow. Check it out for more details and context of Levy’s significance.

Levy opened his gallery in the fall of 1931. The Modern show opened in May of 1932. If nothing else, this essay reflects Levy’s thinking of photography and art, cinema and pai.nting, at an early stage of his involvement with a nascent medium. Enjoy.

The Gala As Art As Slideshow

The Gala As Art, greg.org, at #rank 2010 from greg allen on Vimeo.

Here’s the narrated slideshow I did at #rank during Art Basel Miami Beach.

Many thanks to Jen and Bill for inviting me, to Magda for instigating, to all the SEVEN galleries for hosting, and to Michelle Vaughan for sharing her sharp gala insights. And a huge thanks to Jean, whose advice helped structure a drive-by blog post into a more coherent [I hope] argument. And who insisted I go do the talk, even though it meant celebrating our tenth anniversary early and late.

Thanks, too, to the artists and photo sources, including, in random order as I think of them: Andrew Russeth/16miles.com, Artforum.com, Andrea Fraser, MoCA, LACMA, the Rubell Family Collection, Jennifer Rubell, Kreemart, Christoph Brech, Getty Images, Patrick McMullan, the daily truffle, billionaire boys club, Vernissage TV–don’t these credits make you just want to hit play right this second??

The audio’s rough, the aspect ratio wonked out at the last minute, and I’d do better to just rebuild the whole thing rather than adapt my Keynote slides. And while there’s no gift bag at the end, I did manage to edit out a whopping 12 minutes of um’s, pauses, and “wait, I want to go back to the previous slide”s. I guess media training is NOT like riding a bike.

Johns, Merce, Duchamp: Walkaround Time

image: walkerart.org

Welcome to one of the oldest tabs in my browser: the inflatable balloon set for Merce Cunningham’s 1968 piece, Walkaround Time, which is based on Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass, which was made by the company’s artistic director at the time, Jasper Johns.

I’d backed into the pieces–seven cubes of silkscreen-and-paint on clear vinyl, reinforced with aluminum frames–a few months ago, and realized I’d seen them–and not thought much about them–at the opening of the newly expanded Walker Art Center in 2005.

Which I now regret, but which makes Merce’s title resonate a little more. Cunningham dancer and longtime collaborator Carolyn Brown explains that Walkaround Time was a reference to a particular kind of purposeless movement taken from ancient computer history, when “programmers walked about while waiting for their giant room-sized computers to complete their work.” It’s just taken me this long to appreciate–or even to see–the work. And for some great additional links to appear.

I can already tell this is going to go long.

03/2012 UPDATE: Unfortunately, none other than former MCDC stage manager Lew Lloyd informs me that the term “balloon” is not really accurate; they were transparent vinyl boxes fit onto armatures, which could be broken down for travel. Given my noted satelloon bias, I will still think of them as balloons in my heart. For the rest of you, though, remember: not balloons. [end update]

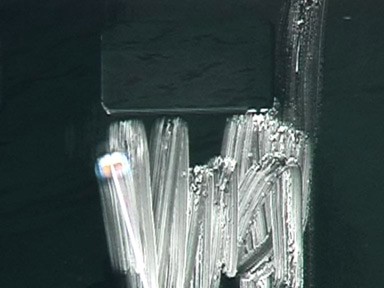

Sea Force One

Christoph Brech is the master of the meaningful tight shot. In Sea Force One, he focuses in on a pair of workers in a small boat who are scrubbing the hull of Francois Pinault’s black yacht in front of Punta della Dogana during the 2009 Venice Biennale.

The work is included in “Portraits and Power: People, Politics & Structures,” at Strozzina in Firenze. It is interesting to compare their writeup of the piece–

We do not know who was on board the yacht – possibly François Pinault himself, the famous French luxury goods entrepreneur and primary investor in the new Venetian exhibition area. Brech has turned his camera on a moment that would otherwise have gone unnoticed, deliberately choosing not to record the sumptuous affirmation of wealth of the yacht. It is the contrast between the size of the latter and that of the small boat, or between the black hull of the yacht and the evanescent white of the soap and of the reflections upon the water, that brings out the greatness of the vessel, the actual size of which we do not grasp. The artist succeeds in moving beyond the façade of power and wealth by stopping at its surface. He seems to be suggesting that the strategy for the construction of an image of power may lie in its antirepresentation: i.e., the “myth” of power is created by veiling or concealing the identity of those who hold it.

–with the artist’s own:

The yacht Sea Force One is anchored in front of a museum at the Punta della Dogna in Venice. The waves of the lagoon are reflected in the black varnish on the ship´s hull.

From a small boat nearby, workers are cleaning the yacht.

A painting emerges from the broad, white trails of foam on the ship´s dark surface, visible only for a short while until erased by cleansing streams of water.

Once again the reflected waves dapple the yacht.

At first read, I thought Brech’s focus on the formalist, painterly abstraction was notably less political than the Florentine curators’ interpretation. And damned if it doesn’t, in fact, look like a negative inversion of a making of film shot in Franz Kline’s studio.

Which immediately reminded me of the interview Felix Gonzalez-Torres did with Rob Storr, which I’ve reprinted and referenced here several times over the years.

I’m glad that this question came up. I realize again how successful ideology is and how easy it was for me to fall into that trap, calling this socio-political art. All art and all cultural production is political.

I’ll just give you an example. When you raise the question of political or art, people immediately jump and say, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, those are political artists. Then who are the non-political artists, as if that was possible at this point in history? Let’s look at abstraction, and let’s consider the most successful of those political artists, Helen Frankenthaler.

Why are they the most successful political artists, even more than Kosuth, much more than Hans Haacke, much more than Nancy and Leon or Barbara Kruger? Because they don’t look political! And as we know it’s all about looking natural, it’s all about being the normative aspect of whatever segment of culture we’re dealing with, of life. That’s where someone like Frankenthaler is the most politically successful artist when it comes to the political agenda that those works entail, because she serves a very clear agenda of the Right.

For example, here is something the State Department sent to me in 1989, asking me to submit work to the Art and Embassy Program. It has this wonderful quote from George Bernard Shaw, which says, “Besides torture, art is the most persuasive weapon.” And I said I didn’t know that the State Department had given up on torture – they’re probably not giving up on torture – but they’re using both. Anyway, look at this letter, because in case you missed the point they reproduce a Franz Kline which explains very well what they want in this program. It’s a very interesting letter, because it’s so transparent.

I guess it’s the curator’s job to overexplain things [?] but Brech’s title and his discussion of the work in terms of abstraction is plenty political in itself.

Art Is Where You See It: YouTube Play @Guggenheim

Though I had considered entering, and I’d sampled a few of the 125 videos on the shortlist, I had planned to not write about the YouTube Play Biennial at the Guggenheim. But then reps from a couple of the event’s sponsors, HP and Intel, asked if I’d guest post about art, video art, and film in their Facebook group, 24|7 Creative, and they invited me to attend the big gig at the Gugg last week. Here is a brief recap of that experience, and how I see it.

[Holy smokes, this is long now, really, unbelievably long. And with a tragicomic surprise ending, too!]

Continue reading “Art Is Where You See It: YouTube Play @Guggenheim”

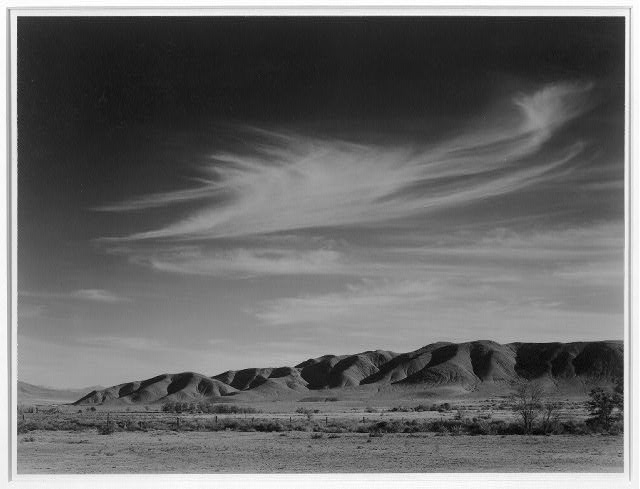

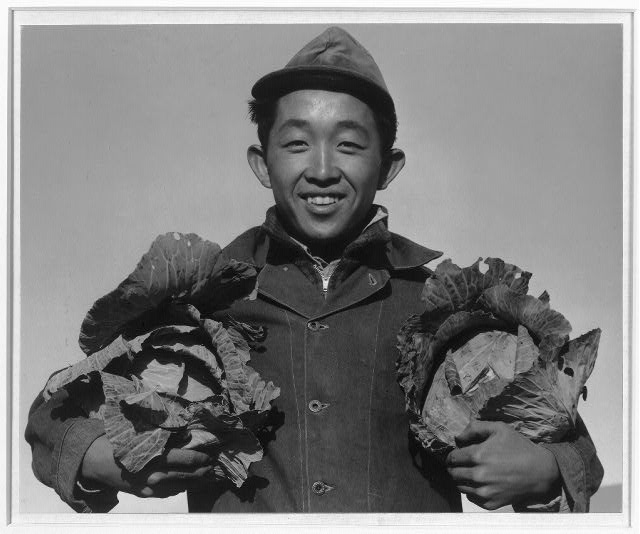

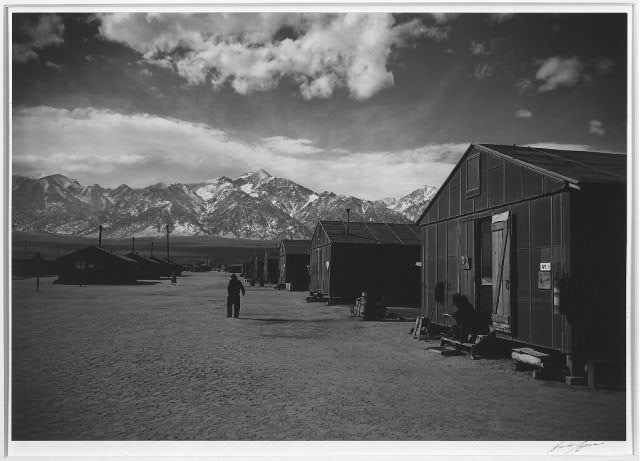

Ansel Adams’ Japanese American Internment Camp Photos At MoMA. Shhh!

Someday this will all look and sound really coherent, I swear. But for going on, wow, 20 years, some of the most powerfully influential photos for me have been the images Ansel Adams took at Manzanar, the desert prison camp where Japanese-American families were interned at the outset of WWII. Deeply outraged that the US government would imprison its own citizens en masse, Adams set off to document the situation in 1943. In late 1944, he published a book, Born Free and Equal, which contained his text and a selection of the photos.

I spent years chasing down a copy of the book. And collecting prints from the series. And working with the Museum. And yet it was somehow only last week that I found out that in November 1944, Adams’ Manzanar photos were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art.

Given that Adams had been asked by Edward Steichen to join his elite Naval Aviation Photography Unit, and that Adams was close with the Modern’s photography curator Beaumont Newhall and his wife, one might think that Adams’ wartime photos would have received the same prominent promotion and large-scale exhibition printing that Steichen’s Power in the Pacific show received a couple of months later.

And one would be deeply and completely wrong. According to the most tepid press release in the Museum’s history,

A series of sixty-one photographs showing the life and activities at a relocation center in California form an exhibition opening in the auditorium galleries of the Museum of Modren Art Friday, November 10, under the title Manzanar: Photographs by Ansel Adams of Loyal Japanese-American Relocation Center. Mr. Adams has also written the accompanying text. The exhibition, an unusual demonstration of the use of documentary photography, will be on view through December 3.

The exhibition is described as “an activity of the Museum’s Photography Department,” and its acting curator, Nancy Newhall. Pull every string he has at the Museum, and still the best Ansel Adams can do is a three-week show in the basement.

Ansel Adams donated his Manzanar photos to the Library of Congress [loc.gov]

Previously: I Mean, Just Look How Happy They Were! [greg.org]

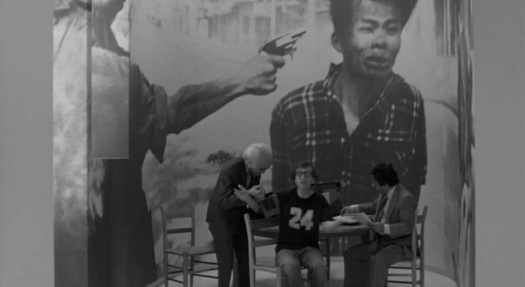

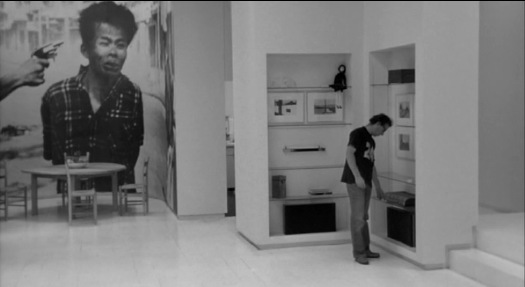

Related: Photomurals In Stardust Memories By Woody Allen [Not Related]

My recent photomural binge has flushed out some interesting comments and suggestions, including one from Craig about the use of a photomural as a key interior design element in Woody Allen’s 1980 film, Stardust Memories.

Allen’s character, filmmaker Sandy Bates, has wrapped the dining room of his Manhattan apartment with a photomural of Eddie Adams’s iconic 1968 AP photo from the Tet Offensive of the shooting of captured VC Nguyen Van Lem by South Vietnamese General Nguyen Ngoc Loan. [above] It was commonly understood to be a universal symbol of man’s cruelty, suffering, and inevitable mortality.

The shocking juxtaposition hadn’t worn off for Richard Woodward, who used the fleeting scene a full nine years later as the opening anecdote for a critique of art’s changing relationship with documentary photography. Titled, with the cloying question mark, “Serving up the Poor as Exotic Fare for Voyeurs?” Woodward seems to complain that the art world, which “favors big pictures and high prices” was messing it up for real [aka “documentary”] photography and serious subject matter:

Perhaps nothing in the film better conveys the twisted soul of the protagonist who, in his misguided need to project, magnify and expiate his guilt over the world’s pain, has turned a moment of unforgettable horror into a decorative mural. It’s a macabre joke about the heartless vanity that can underlie high-minded gestures; and it’s a warning about photography, which can lose any claim as a moral force after countless reproductions on the wrong kind of wall.

But then he ended with this:

Many contemporary artists, like Alfredo Jaar, Sarah Charlesworth and Louise Lawler, are making work in which the use of an image – its presentation by the news media or a museum – becomes the grounds for critical scrutiny in a context of the artist’s own devising. A persistent theme of art in the late 80’s has been the struggle to patrol and examine the use of images. At the very least, many artists seem to be saying, it is time to stop averting our eyes.

Only this turns out to be exactly what Woody Allen was doing a full decade earlier.

Whether it’s Supergraphics or Stephen Shore’s Architectural Paintings or a Bloomingdale’s furniture showroom, there has to be some context or precedent I’m missing here, otherwise Woody Allen should be figuring directly into the history of the emergence of the Pictures Generation.

Because the heavily stylized, black & white Stardust Memories turns out to use photomurals and their relatives as crucial thematic and visual elements.

First off, Allen has said that most of the film actually takes place in his character’s head. Even his apartment, which is nominally in the film’s reality, “is really a state of mind for him. And so depending on what phase of life he’s in, you can see it reflected in the mural.”

Though Adams’s photo is often mentioned, and the stills above are common, I couldn’t find images of any of the other murals. So I just rewatched Stardust Memories [at high speed] and pulled out all the ones I could find. I’d hoped that I could find some discussion of the murals and the film’s design from production designer Mel Bourne, but so far, nothing. Bourne did several films with Allen, including Annie Hall and Manhattan, But he also did the production design for Fatal Attraction and, awesomely, the pilot for Miami Vice. Anyway, they’re all after the jump, because, maybe some people might want to skip them? Not me.

Continue reading “Related: Photomurals In Stardust Memories By Woody Allen [Not Related]”

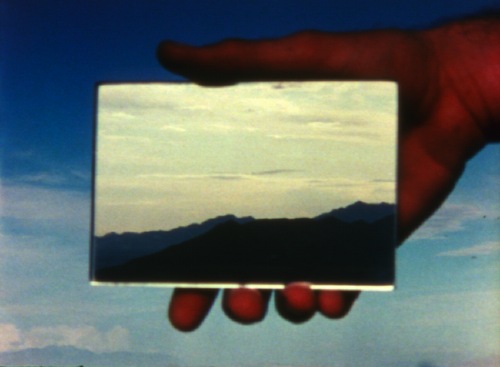

Hand Held Day: Time Mirror Displacement by Gary Beydler

Holy smokes, Gary Beydler. A Los Angeles experimental filmmaker whose 1974 time-lapse silent short, Hand Held Day, was just mentioned by Steve Roden. It’s incredible.

Youtube user austinstein posted this version in 2007, before Beydler’s too-small body of work was restored, so the color is awful, but you can get the idea. Over the course of a day, Beydler shot two rolls of Kodachrome film in the Arizona desert, with the camera pointed east, and the mirror pointed west. The sun and sky did the rest.

On his blog Preservation Insanity, Mark T told the story of taking a leap of faith and restoring Beydler’s last film, Venice Pier, sight unseen in 2007. It’s an journey down the pier, shot in out-of-sync time lapse over the course of a year. It sounds beautiful. Unfortunately, Mark’s blog post was prompted by news of Beydler’s death in January 2010.

To Gary Beydler [preservation insanity]

four of Gary Beydler’s films are available for rent via Canyon Cinema [canyoncinema.com]

The Unoriginal Copy

Dear Art World,

Please arrange the following on a 2×2 grid for me? Or maybe a spectrum? Because I cannot:

Eve Sussman’s 89 Seconds at Alcazar (2004), which I quite like, but:

Peter Greenaway’s Nightwatching (2007) and his cinematic projections on the Last Supper.

Philip Haas’s 2009 filmic re-creations of five paintings from the Kimbell Museum:

The Laguna Beach Festival of the Arts’ Pageant of the Masters tableaux vivants (1933-present):

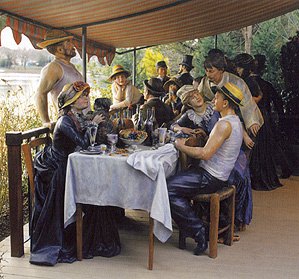

Seward Johnson’s bronze re-creations of well-known paintings (1994- too long), such as those shown at the Corcoran in 2003:

And his blown-up re-creation of Grant Woods’ American Gothic (2009):

And the gigantic fiberglass WTF of Philip Haas’s Arcimboldo-ish sculpture that was being installed at the National Gallery the other day?

Having recently made some copies of someone else’s art myself, I really want to know. Because if this is where it leads, I’ll just go back to finance right now.

Bernd & Hilla Becher Made A Movie. In Color.

And so far, I can’t find it anywhere:

UEZ: when your work first started to appear and was classified as Conceptual art, did you have a secure visual language which you knew would be viable over time? Or could you have arrived at completely different forms of presentation, or made your photographs the basis for videos?

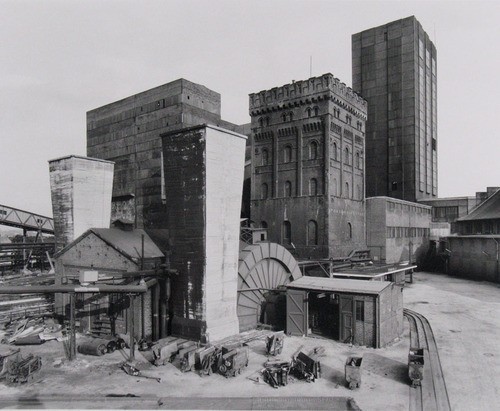

BB: We did make a film once, on the Hannover mine.

HB: Actually, there’s no need at all to talk about failures.

BB: Because that was such an enormous complex. We made a film about it because we wanted to show the atmosphere. Then we looked at the shots, still uncut, and were totally disappointed.

UEZ: How did you make the film?

HB: We borrowed a 16mm camera from Sigmar Polke. The advisor was Gary Schum, in part, who has made a load of beautiful artist films, with Gilbert and George, for example. The idea was that this colliery was not a tightly knit conglomerate, as is usually the case, but rather a diffuse structure held together by belts, by roads.

BB: The atmospheric element was important. On top of that, we were in a hurry. We thought that if we photographed our way through the whole plant, it would take years. Then we made the film in two or three days.

HB: The thought was to drive through this very extensive industrial estate, to show the connections among preparation plant, winding tower, power plant and cokery. But as it turned out, there was so little movement there that the only movement in the film was provided by the camera.

UEZ: Because the colliery was already shut down?

HB: No. Strictly speaking, if you look at a mine like this, the only thing that moves is the wheel of the winding tower. I was thinking at the time of the early Charlie Chaplin films, where the camera sits on the tripod and everything else moves in front of it. Or Hitchcock’s film Rope, which takes place in one room.

UEZ: How strange that you give us these examples, as in fact you didn’t let the camera stay still.

HB: But panning the camera, up and down, right and left–that was no good.

UEZ: When did this experiment take place?

BB: 1973-74.

UEZ: Did you destroy the film in the end?

BB: No.

UEZ: We’re talking about a black-and-white film?

BB: No, it was in color.

That’s from an interview the Bechers did with Ulf Erdmann Ziegler in 2000. It was originally published in Art in America in 2002.

The Hannover Coal Mine was one of ten mining sites the Bechers photographed as early as 1966, but with a concentration in 1971-74, and presented in an “un-Becheresque” way: by site, not by typology. The Van Abbemuseum acquired one portfolio, 85 prints of the Hannibal Mine in Bochum, in 1976, but most of the hundreds of images from each site were unpublished negatives.

And at the time of the interview, the SK-Stiftung in Cologne [which houses the couple’s portfolio archive], began working to process and print images. They did a show, which traveled to the Huis Marseille in the Netherlands. And a catalogue, Zeche Hannibal (Coal Mine Hannibal), which sounds rather interesting.

Hannover Mine 1/2/5, Bochum-Hordel, Ruhr Region, Germany, 1973, Bernd & Hilla Becher [via moma]

As it happens, 200 of over 600 photos the Bechers made at Hannover have just been published in their own book. Zeche Hannover (Hannover Coal Mine) came out in Germany in July.

And it looks like MoMA acquired a selection of the Bechers’ mine landscapes in 2008. When seen together, they end up forming a higher-level series, a typology, not of structure, but of site. So they’re looking more Becheresque all the time. I’d still like to see that film, though.