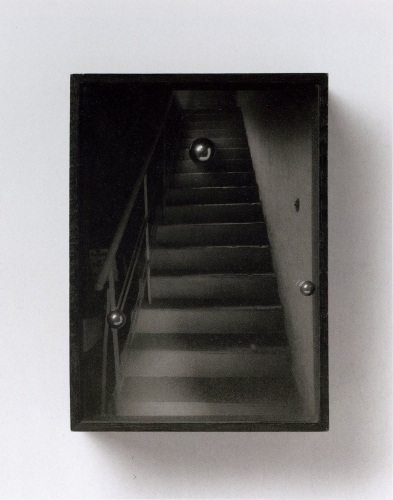

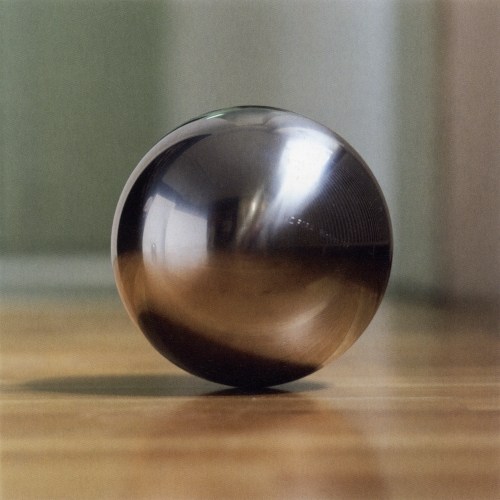

Andy helpfully pointed out this mirrored glass ball, which I’d missed in the catalogue for Phillips’ upcoming design auction.

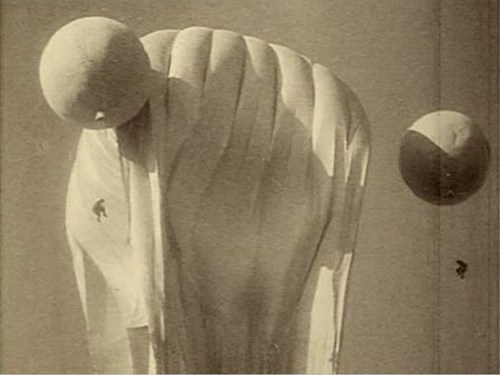

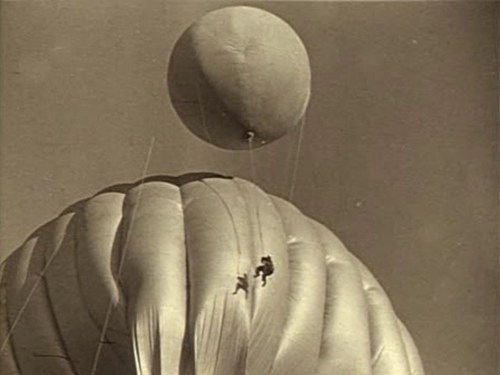

Everyone knows the Bauhaus was a huge party school. And during the Winter 1929 semester, Oskar Schlemmer had put an extra emphasis on partying, “to preserve the character of the Bauhaus community.” And so what had started as a metal shop farewell get-together for Marianne Brandt on 9 February 1929 with the tasteful theme, “Church Bells, Doorbells, and Other Bells” [Hmm, one of the few cases where it sounds better in German: “Glocken Schellen, Klingel Fest.”] became a raging, balls-out “Metallisches Fest,” which took over the entire, iconic Dessau building. As MoMA’s 2009 catalogue tells it:

The pure qualities of metal lend themselves to costumes with decorations that magically transform the Bauhaus through shimmering, reflective surfaces. According to Schlemmer, “The Bauhaus was also attractive from the outside, radiant in the winter night: the windows with metal paper stuck inside them, the light bulbs–white and colored according to the room–the views through the great glass block–for a whole night these transformed the building of the ‘Hoschschule fur Gestaltung.”

Party on, Oskar! I’m glad the Bauhaus Arkiv is so careful with all their materials, they don’t let anything more than a postage-stamp-sized image slip through to the web.

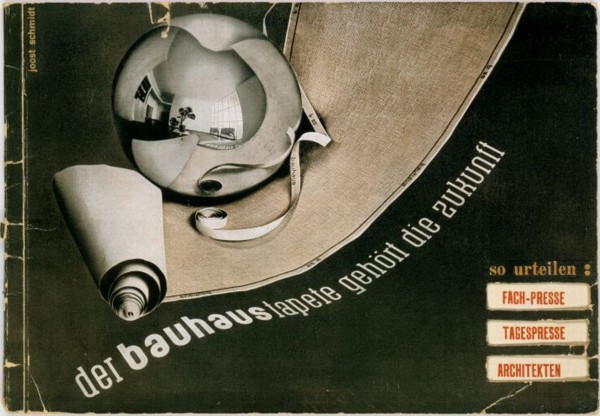

I can’t remember where I found this copy of the Bauhaus wallpaper sales brochure which came out soon after the Fest, but it wasn’t the Bauhaus Arkiv:

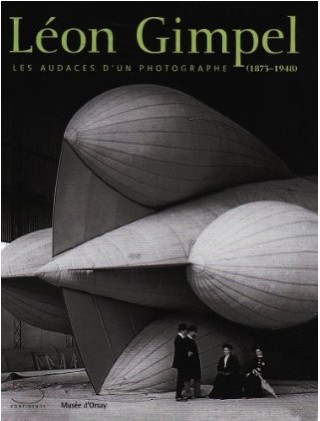

And Marianne Brandt Geselleschaft only had a tiny version of this Brandt self-portrait taken a mirrored glass ball.

Though to their credit, the firm did throw another Metallische Fest in 2005, even if the guest of honor had long since departed for good.

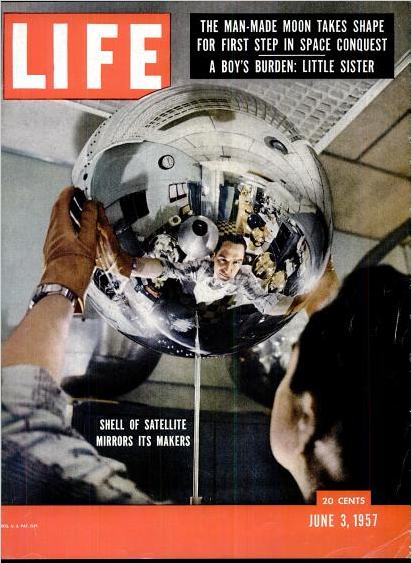

Lot 130 Bauhaus Mirror Ball, est $5-7,000 [phillipsdepury.com]

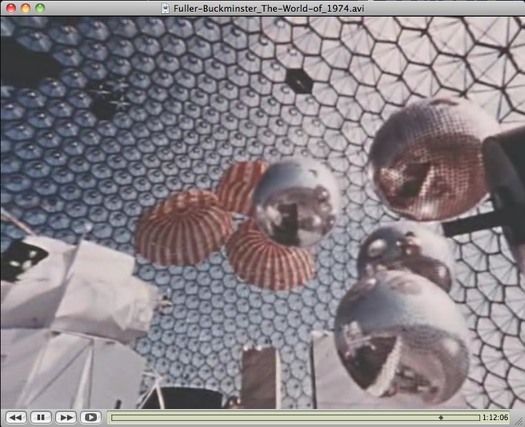

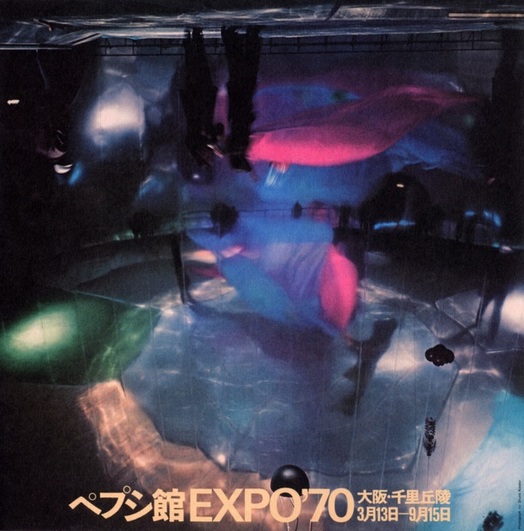

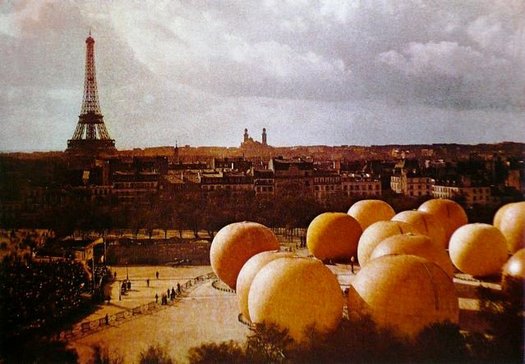

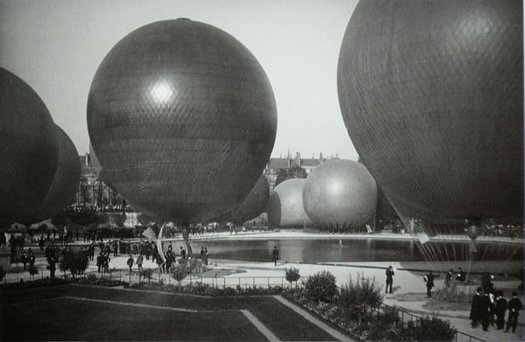

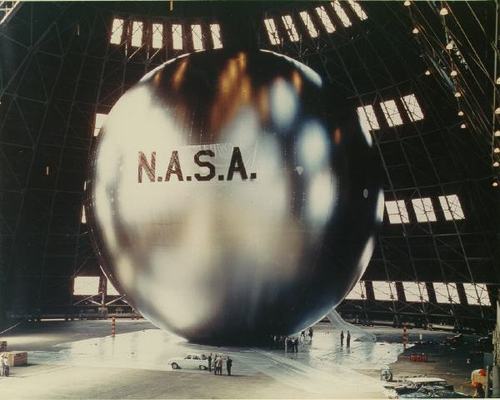

Previously [as in previously on greg.org, but after the Bauhaus, obv]: Shiny Space Balls? Yes Please!

Oh wait, Muybridge was before the Bauhaus

Artwork become landscape

Artwork become landscape

Everyone [sic] probably has the story tucked away in their head that science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke was the

Everyone [sic] probably has the story tucked away in their head that science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke was the