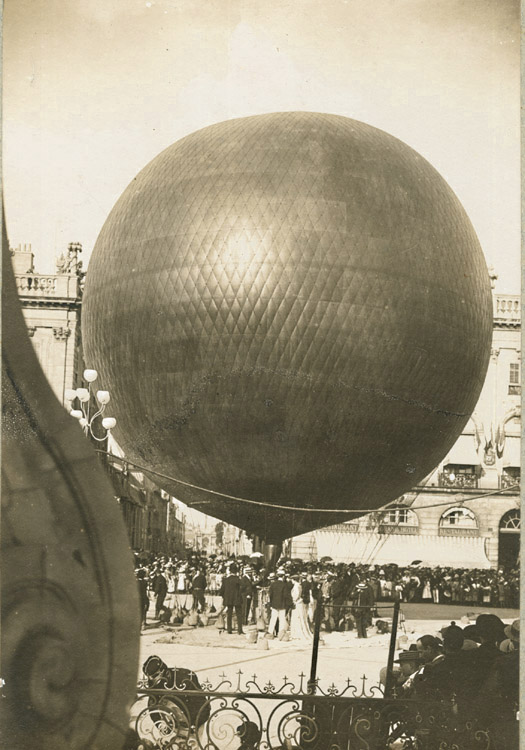

Rather than post this beautifully composed 1895 photo of Henri LaChambre’s rather awesome gas balloon inflated at Nancy, I should’ve freakin’ bought it by now.

Of course, my problem is that, now that I’ve seen it, I’ve filed it away for future flea market reference, where I’m sure I’ll just stumble upon a photomural-sized print of it for a euro.

Anonymous – Henri Lachambre and His Balloon at Nancy, France, $450 [vintageworks.net, thanks to whoever sent this to me, I forget, sorry]

Previously: Les Ballons du Grand Palais

Category: satelloons

Tinguely’s ‘Black Tie Dada,’ Or Worlds Collide In MoMA’s Sculpture Garden

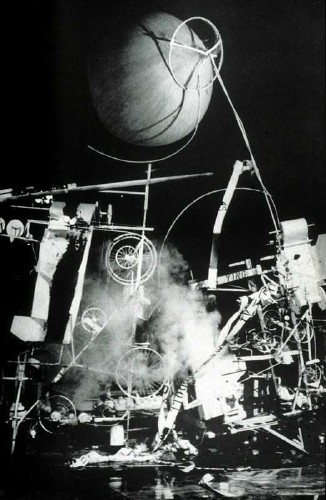

So fantastic. When I started digging around a bit on its history, I just assumed Jean Tinguely’s kinetic masterpiece, Homage to New York, would itself be the most interesting find. Not quite.

After making a name for himself in Europe with his “meta-matics,” automatic drawing machines, Tinguely came to New York in the early winter of 1960 and spent three weeks building Homage in the Sculpture Garden of the Museum of Modern Art. Billy Kluver helped him build the self-destructing sculpture from parts scavenged, thanks to multiple trips with curator Peter Selz, from the Newark dump.

Homage was performed? exhibited? destroyed? before an invited audience of around 250 on the evening of Thursday, March 17, 1960. I haven’t figured out who was there, but in a 2008 Brown Bag Lunch Lecture on the work, Columbia art historian Kaira Cabanas said someone referred to it as “Black tie Dada,” which might have just earned it a mention in my history of the gala-as-art movement.

The popular story is that the piece somehow malfunctioned, caught fire, and prompted NY firefighters to intervene just 30 minutes into the 90-minute event. Actually, even the Museum’s description of its own artifact from Homage says this. But it also has the incorrect date for the event, March 18, so perhaps not.

March 18 is the stated publication date for the Museum’s press release [pdf], though, which said the machine would be “set in motion” and “shown” only from 6:30 to 7:00. So it’s possible that everything went as planned.

[Also, people apparently picked through the wreckage for souvenir fragments, but I can’t find any mentions of them surfacing. Besides MoMA’s conveniently self-contained hunk, above, the Tinguely Museum has a few manageable pieces.]

But really, the press release and the pamphlet/handout prepared for the event, is a gold mine of quotes and commentary. I double dog dare you to think of Alfred Barr the same way after reading his statement:

Forty years ago Tinguely’s grandadas thmbed their noses at Mona Lisa and Cezanne. Recently Tinguely himself has devised machines which shatter the placid shells of Arp’s immaculate eggs, machines which at the drop of a coin scribble a moustache on the automatistic Muse of abstract expressionism, and (wipe that smile off your face) an apocalpytic far-out breakthrough which, it is said, clinks and clanks, tingles and tangles, whirrs and buzzes, grinds and creaks, whistels and pops itself into a katabolic Gotterdammerung of junk and scrap. Oh great brotherhood of Jules Verne, Paul Klee, Sandy Calder, Leonardo da Vinci, Rube Goldberg, Marcel Duchamp, Piranesi, Man Ray, Picabia, Filippo Morghen, are you with it?

I am, Brother Alfred, I am! Say amen, somebody!

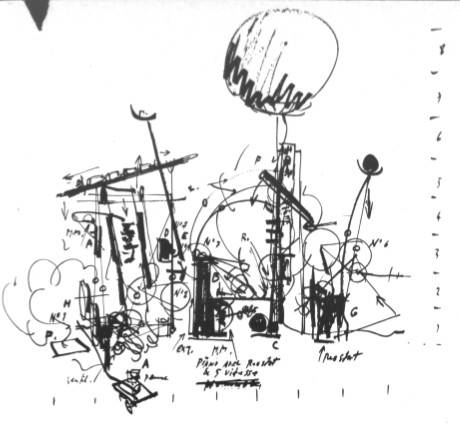

Ahem, also, did you see that weather balloon that was part of the piece? Here’s the sketch from the brochure:

And here it is, atop another performance photo, probably, again, from David Gahr:

The brochure quote from original Dadaist Richard Huelsenbeck adds back some of the fatalistic frisson that can be lost in a nostalgic, artifact-centered look back at a troubled historical moment:

There are times in human history when the things men have been accustomed to doing and have long accepted as a part of the established order erupt in their faces. This is the situation right now–the universal crisis is forcing us to redefine our cultural values. We are like the man who is astonished to discover that the suit he has on does not fit him any longer. Religion, ethics, and art have all transcended themselves, especially art, which, instead of being art as we know it, has come to demonstrate man’s attitude toward his basic problems. So it is senseless to ask whether or not Tinguely’s machines are art. What they show in a very significant way is man’s struggle for survival in a scientific world…

He goes on to call Tinguely a Meta-Dadaist, which is quite nice. And to someone who lived through the horrors that produced it, it makes more sense than being nostalgic for Dada.

Anyway, Robert Rauschenberg was an early fan of Tinguely’s, and soon became an exhibition collaborator. Last winter the Tinguely Museum in Basel had a show about their working friendship. Which featured this awesome photomural of Homage To New York:

It’s probably from one of the performance images David Gahr shot for Kluver and MoMA. I don’t think it’s archival in any way, but it’s a great way to evoke the physical presence and scale of the assemblage.

I can’t find it now, but someone wrote how Tinguely kind of announced the Kinetic Art movement with Homage To New York, and then declared its end with “a similar” installation in front of the Duomo in Milan in 1970. Which cracked me up, because, hello, have you seen what Tinguely put in front of the Duomo in 1970? And was that similar to what Homage to New York was? Because I doubt it, but if so, wow.

Actually, let’s go to the tape. Or the film. Because D.A. Pennebaker shot the event, and made a documentary short, Breaking it up at the Museum, which features Tinguely previewing the piece, some details of the machine in motion, the takedown, the crowd, the applause, Tinguely’s curtain call, and a couple of audience member reactions:

Jean Tinguely – Homage to New York (1960)

“It’s one of the most exciting things I’ve seen in the art season in New York.”

“Why?”

“Well, it was something new, and visually, it was marvelous.”

“I felt like being in ze Twenties again.”

As Patrick said, a time machine.

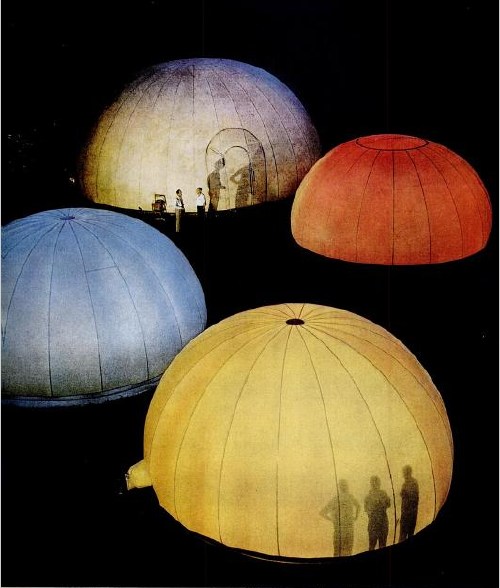

‘Nylon Airhouses’ By Frank Lloyd Wright

I’m thinking I might have to change the name of this blog to Holy Smokes, but holy smokes, did the past ever look more futuristic than it did in the pages of LIFE Magazine, November 11th, 1957?

That’s where I found the house of the future of the past, Eduardo Catalona’s Raleigh House, in the issue titled, “Tomorrow’s Life Today – II.” There’s also THE Monsanto House of the Future from Disneyland. There’s an Alcoa aluminum beach cabana thing; the cover’s got a transparent, inflatable pool dome; a three-generation family of mimes, I guess, laying around in black leotards on a candy-colored assortment of foam slab furniture. And then there’s this:

Nylon Airhouses pop up on a university campus in Kentucky. Made of U.S. Rubber Company’s Fiberthin, a vinyl-covered nylon fabric four times as strong as waterproof canvas yet 40% lighter in weight, domelike houses are kept up by air, pumped in by small motors. They are anchored at base by a ballast ring of sand or water…

According to Sean Topham’s Blowup: Inflatable Art, Architecture & Design, this “Fiberthin Village” or “Rubber Village” of airhouses was designed by none other than Frank Lloyd Wright.

Actually, according to Billboard, US Rubber was manufacturing the warehouse-sized airhouses, but the domestic-scale models were being produced by the Irving Air Chute Company of–aha–Lexington, KY. Now that you mention it, they do look rather parachutish.

But why is Billboard reporting on repurposed military technology? Because in the summer of 1957, airhouses were competing against an international chain of “balloon bijoux” for the right to stage concerts in Central Park. What’s “most appealing” about these inflatable concert venues, we learn, is that they promised “the virtual elimination of large crews of roustabouts to set [them] up.”

In 1961, The Rotarian reported that, in addition to U.S. Rubber–which also introduced Keds, by the way, in 1917–a major player in the growing inflatable dome building industry was G.T. Schjeldahl, who also fabricated the Project Echo satelloons. See, it all comes back around.

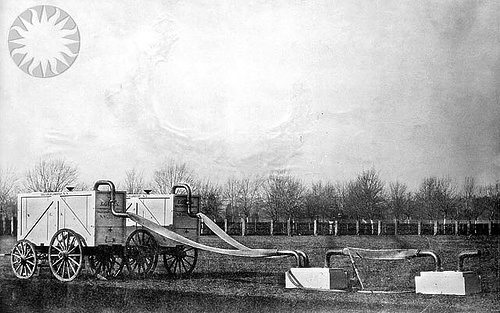

Lowe’s Balloon Gas Generators: The Making Of

About this time last year, while pondering the ur-satelloons that were Prof. T.S.C. Lowe’s Civil War-era aerial reconnaissance balloons operated for the Union Army, I was struck by the idea of re-creating the rather awesome-sounding and -looking portable hydrogen gas generators [above] Lowe designed and had built at the Washington Navy Yard in the fall of 1861.

I’m glad to report that the research for that project is moving ahead, thanks to the accidental discovery of the apparently definitive history of their making in Frederick Stansbury Haydon’s 1940 tragically unfinished classic, Aeronautics in the Union and Confederate Armies: With a Survey of Military Aeronautics Prior To 1861. As NASM Senior Curator Tom Crouch put it in his foreword to the 2000 reissue of the book, retitled as Military Ballooning During the Early Civil War,

Aeronautics in the Union and Confederate Armies remains not only the basic account of the creation and early history of the Federal Balloon Corps, it is recognized as something of a minor classic of historical scholarship. While reviewer Paul Angle feared that readers would find the level of detail and sheer bulk of the documentation daunting, he also recognized it was “a study quite likely to be definitive.”

In fact it is Haydon’s uncompromising scholarly rigor and his attention to the smallest detail that gives the book its extraordinary power. The author tells us how much fabric was used to manufacture every balloon that saw federal service, and he provides the formula for the varnish used to seal the envelopes. He explains the technical details of the mobile gas generators that Lowe designed to inflate his balloons in the field and provides the precise cost of the rubber hose used in their construction. And what color were those generators? Light blue. Haydon found the receipt for the paint.

“Pale blue,” we read, “with bold black lettering bearing the legend, ‘Lowe’s Balloon Gas Generator,’ and a serial number.” Twelve were built and put into service.

Since he consulted a great number of historical artifacts without mentioning one, I must assume that no generator survived for Haydon to inspect.

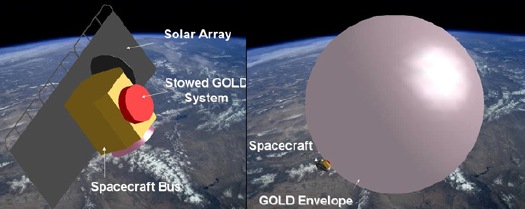

Space Race

And in other Just Cold Stealin’ My Satelloon Idea Before The Fact News:

This has been stuck on my iPad for way too long. At a space flight conference a couple of months ago, the Global Aerospace Corporation announced their GOLD program, the Gossamer Orbit Lowering Device for controlled satellite de-orbiting.

GOLD is a commercial venture designed as a solution for managing the clutter in low-earth orbit [LEO]. It’d be available as an option for future missions, or as its own mission for dealing with space junk that’s already out there.

The idea is to attach a satelloon-style inflatable sphere up to 100 meters [!] in diameter to a satellite, thereby degrading its orbit much more quickly, and letting you steer it to a fiery death in the atmosphere. Though Global only just announced it publicly, they received a patent for the GOLD system it in 2004.

Conceptually, it couldn’t be more different than my satelloon idea; Global Aerospace is pushing hardcore utility and cost-effectiveness, while I’m going for art’s utter uselessness for anything but sheer experiential and aesthetic benefit.

But from the ground, I suspect it’ll be pretty hard to tell the art satelloons from the functional satellite killers. I will need to keep an eye on these people.

Global Aerospace Corporation | GOLD [gaerospace.com]

Balloon device for lowering space object orbits [google patents]

Oh, Ok, Bring It, Charles Gwathmey

So there I am, just driving to the Berkshires for an interview, minding my own business, when suddenly I come around the bend into Springfield, MA, and there’s Charles Gwathmey throwing a 100-foot silver sphere in my face!

And I’m all, fine, you and the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame win this round, but I will be bringing my satelloon game in the playoffs, my dearly departed friend.

Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame (2002) [gwathmey-siegel.com]

Sedia Veneziana, Chaise Bordelaise

via la_biennale

So Venice is not a total bust. Raumlaborberlin have installed their 2006 mobile inflatospace sculpture, „Das Küchenmonument,” in the Giardini.

And next to it is The Generator, an on-site workshop for knocking together “sedia veneziana,” which are not just autoprogettazione-style chairs…

via br1dotcom

they’re “future particles of the generator-space-structure,” modular building elements of both social space and structure. autoprogettazione stacking chairs. Awesome.

Which, of course, is related to their exhibition for Arc en Reve in Bordeaux last year, “Chaise Bordelaise.”

“Chaise Bordelaise” consisted of a 3x3x1m pile of pre-cut, reclaimed lumber, instructions, and some tools. Visitors made some chaises, then took them home.

It’s basically an Enzo Mari x Felix Gonzalez-Torres mashup. If greg.org had tags, this post would be giving me a tagasm right now.

Raumlaborberlin: what’s up? exhibitions [raumlabor.net via archinect]

Chaise Bordelaise [raumlabor.net]

related: proposta per un’ auraprogettazione

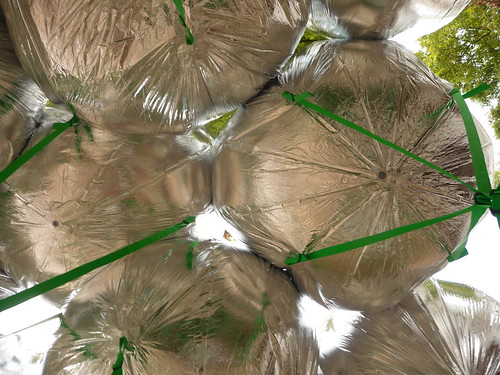

Venetian Mirror

via tsaaby

Yeah, so I’d been poking around flickr for a while, looking to see how MOS’s project for the US Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale turned out. Because well, because.

via Erika-Milite

And hmm. What is it about it? The green straps? Should the weather balloons have been upside-down, so gnarly knots and straps take a backseat, and the smoother, more reflective surface is visible instead of pointing to the sky? Maybe instead of straps, string a net across the courtyard, and attach the balloons from above, or maybe let the balloons float up against it to find their own structure?

via

br1dotcom

Do the balloons just not have enough gas, or enough gores?

Because right now, I’m rethinking my entire satelloony look.

I Didn’t Know ‘What I Did On My Vacation’

Holy smokes, Gordon Hyatt, I didn’t know what you did 44 summers ago.

Among the episodes of CBS’s news program “Eye on New York” which were acquired by The Museum of Modern Art in 1967 for their Television Archive of the Arts is “What I Did On My Vacation,” which, wow. It was a series of Happenings. In the Hamptons. Conceived and produced for television, by television.

According to Jeff Kelley’s Childsplay: The Art of Allan Kaprow, the producer of “Eye on New York,” Gordon Hyatt, approached Kaprow in the summer of 1966 with the idea of staging a series of Happenings across the Hamptons over the course of an August weekend:

The general idea for Gas, which was largely conceived by Hyatt (and supported in part by Virginia Dwan of the Dwan Gallery), was to interject a series of Happenings into the leisure activities of summer vacationers and locals, who would presumably be caught unawares as they disembarked at the railroad station, took the ferry, swam at the beach, and so forth.

Kelley’s exhaustive recounting of Kaprow’s Happenings is invaluable for getting a sense of what actually happened, but it’s also full of uncritical assertions, revisions and spin. It’s almost as if Kaprow was trying to distance himself after-the-fact from a TV spectacle he readily agreed to, but which he later came to regret. Interesting.

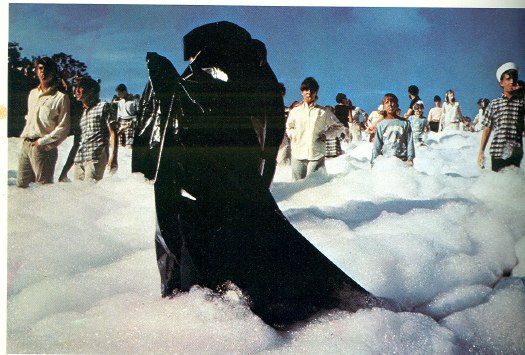

Gas began on Friday August 5th. A parade of oil drums, weather balloons, and homemade hovercraft met the city crowd as the LIRR pulled into Southampton. [photos are documentation by burton berinsky, not stills from the show] On Saturday, Kaprow brought bands, smoke bombs, and skydivers to Coast Guard Beach [now Atlantic Avenue Beach] in Amagansett, where Frazier inflated a giant black phallus of a skyscraper-shaped balloon. Or as the flyer put it, “Procedure: Children and adults may help release helium balloons, frug on the beach, help to start plastic skyscraper, swim.” [Note: If you think you might retell this story sometime, frug is pronounced froog. It is the ultimate White Guy Shuffle.]

From Amagansett, the Happening crew hustled out to Montauk Point, where the fire department was waiting to pump gallons of flame-retardant foam over the cliffs and onto the beachgoing audience.

On Sunday, after arranging for three bedsful of nurses to meet the Shelter Island ferry, Kaprow staged two decidedly North-of-the-Highway Happenings in Springs for the kids: a car painting picnic at the auto junkyard, and a foam-filled relay race at the town dump. Alastair Gordon, who was 13 at the time, wrote about participating in the dump event in his awesome book, Spaced Out: Radical Environments of the Psychedelic Sixties, which was excerpted in the Easthampton Star in 2008:

Someone was barking through a megaphone: “Keep moving . . . not too fast . . . don’t look at the cameras. . . .” We were told to move deeper into the sandy pit, slowly, toward a group of people wearing black plastic capes at the bottom of the slope. We wore pink buttons that read “GAS — I’m a Happener” and blew whistles as we marched downward. Stacks of multicolored oil drums were pushed from a ledge, and we were told to roll them back up the slope through the sea of firefighting foam.

I guess I was too young to pick up on the sexual allusion at the time, but the foam felt weirdly comforting as it oozed around my ankles and bubbled up to my waist. Mud stuck to the drums and made them difficult to roll, but we kept pushing because there were men with cameras, and we were going to be on TV.

Though they should have been obvious going in, Kaprow’s problems with Gas seem evident in Gordon’s account: the Happening didn’t just ‘happen,’ it was staged and performed for cameras:

Though nearly everyone, including Hyatt, deemed Gas a success, Kaprow saw it as a reversion to theater. It was a string of “spectacular” Happenings intended more to be seen than enacted, both during the events and on television.

The feedback loop Kaprow loved had been replaced, he found, with

the false feedback of narcissism on a mass-media scale, in which the culture, through the mirror of television, watches itself having a gas.

In the end, the experiment failed because Gas participated in the popular cliches of what Happenings were.

And the avant-garde was inextricably linked with the leisure entertainments of affluent youth. All of which, well, guess what? Whatever Kaprow’s later regrets about it, Gas seems like a peculiar, even unique experiment in corporate-avant-garde collaboration. And the involvement of Hyatt, a member of MoMA’s Junior Council and Dwan in the transform “What I Did On My Vacation’ from arts journalism into public art.

At the very least, it’s a vast improvement over the cliche-ridden, made-for-TV art happenings they’re throwing up these days. [OR. Does good Art-for-TV really just equal failed Art-for-TV + time?]

“What I Did On My Vacation” was shown at Hauser & Wirth’s Kaprow restaging last year, but I can’t find it online. No problem, though, because the National Film Network has a DVD for just $22.

“What I Did On My Vacation” aired on WCBS on Sunday, September 11, 1966.

Vintage coverage from TIME: Gas: Happenings in the Hamptons [time.com]

Two Degrees Of Project Echo: Les Levine’s Slipcover

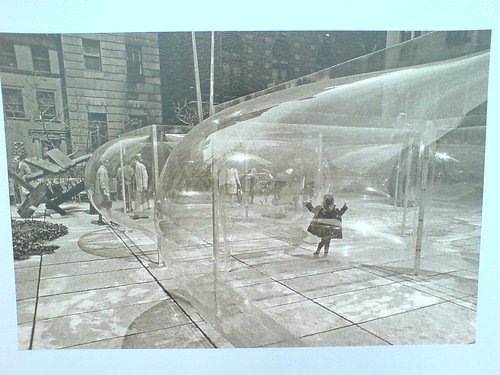

Holy smokes, people, just watch how these things turn out. In April, I spotted this photo at MoMA; it was in the second floor hallway just past the cafe, with no caption, and a date: 1970. I spent a few weeks trying to search up the name of the artist who made this remarkable, undulating acrylic structure in the Garden, to no avail [MoMA’s records didn’t have any more info about the photo.] I looked through the archive of shows, trying to match it, nothing.

Look at that thing, though, it’s like an ur-Dan Graham. an ur-Greg Lynn, for that matter. A more permanent Ant Farm inflatable. Suddenly, it occurred to me to ask John Perrault, who’s probably forgotten more than I’ll ever know about postwar art in New York. Sure enough, he nailed it: Les Levine. Star Garden, but 1967, not 1970.

Turns out 1967 was a great year for Levine–actually, looking through his works at the Center for Contemporary Canadian Art, a lot of years were great years for Levine. The Silver Environment (1961), vacuum-formed mirrored plastic? fabric? The perceptually disorienting acrylic bubble structures like Star Garden or Supercube Environment (1968)?

Disposables (1968) [above], a pop-minimalist grid of vacuum-molds of household objects, sold cheap and meant to be thrown away when their moment is over? Wow, Levine’s Restaurant (1968), New York’s only Canadian Restaurant, operated as a artist project, like Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food or Allan Ruppersburg’s Al’s Cafe, only earlier? Is that really TV test pattern print clothing there in 1978?

And then there’s Slipcover, a 1967 installation at the Architectural League [image via], which ran concurrently with Star Garden: three rooms covered in sheets of mirrored Mylar, where the space is constantly in flux because of the giant Mylar balloons inflating and deflating. The NY Times article shows Levine working on a balloon while one Linda Schjeldahl seals the edges of the Mylar wallcovering. Schjeldahl, Schjeldahl, where have I heard that name before?

Of course! The University of North Dakota’s archives of Gilmore Schjeldahl, founder of the Sheldahl Company!

The Company was the primary contractor for the Echo II Program. There are also files which contain information about the Echo I and II satellite balloons, as well as samples of Echo I and Echo II skins, and a file containing information about an art exhibition by artist Les Levine in 1967, at the Architectural League in New York City, which featured rooms made of Sheldahl’s Mylar laminates.

Billy Kluver, whose company Bell Labs operated the Project Echo satelloons, introduced Andy Warhol to Mylar and helped him make his 1966 Silver Clouds.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer of those satelloons supplied the same Mylar for Les Levine’s 1967 Slipcovers. Who had some help installing from his friend Linda Schjeldahl, the daughter-in-law of the company’s founder. A friend who, like her husband, Peter, was somewhat involved in the New York art world at that point.

If You Love greg.org, You’ll Love History Detectives!

Wow, I knew about the Moon Museum segment because Jade Dellinger emailed about it. But I didn’t know the first episode of this season’s History Detectives also included a whole segment on satelloons and Project Echo. I love how they search for satelloons online–and then crop out the top few search results.

I guess if the Detectives suddenly discover an undocumented Richard Neutra house in Utah, I’ll have to start making some calls. Meanwhile, watch History Detectives on your local PBS station! I’m sure you’ll like it! [thanks cliff for the heads up]

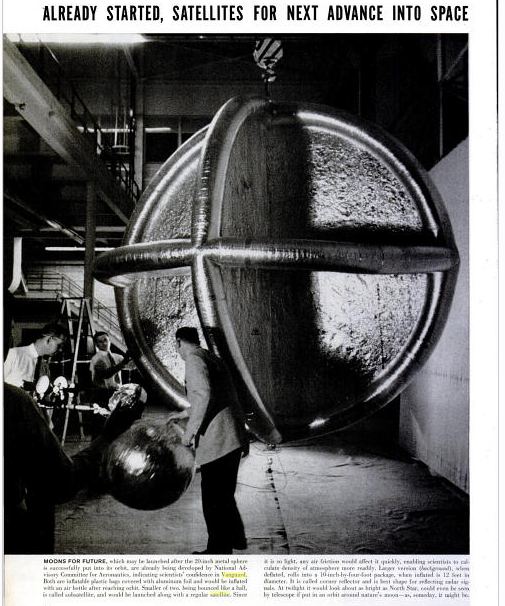

Corner Reflector, Or Rediscovering An Early Satelloon

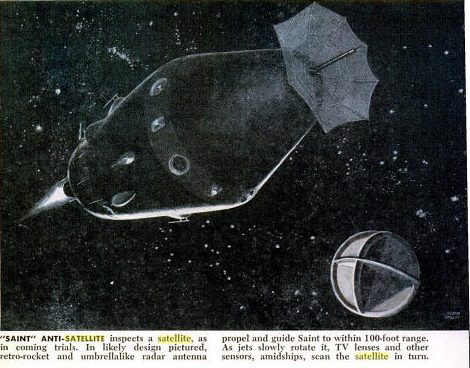

This one’s been sitting on my desktop since April when I posted about that Jan. 1961 Popular Science article about how they made the Project Echo satelloon on a long table with giant clothespins. It was in May, only a couple of months after NASA’s peaceful communications satelloon was made freely available to the world, that Pop Sci informed us of Project Saint, the US Air Force’s program to put the “First Warship In Space.”

That’s Saint on the left up there.

Saint, we read, would disable enemy satellites using one of four techniques: spray paint [for spy cameras’ lenses]; sand [for simulating meteor shower damage]; solar mirrors [for roasting electronics]; or an H-bomb.

Project Saint was canceled in 1962 before any test launches were accomplished.

Oh wait, it wasn’t since April; it was since March. That’s right, April was when I recognized the target, the intersecting circular satelloon depicted on the right. It was called a corner reflector, designed to optimize radar wave reflection, and it was included in the https://greg.org/archive/2010/03/23/shiny_space_balls_yes_please_ill_take_two_no_four.htmlincredible LIFE Magazine cover story from June 3, 1957 about Project Vanguard and the race to launch “the first man-made moon,” a race the US would lose a few months later.

See? Here it is, behind the guy bouncing a smaller Mylar satelloon:

US Plans First Warship in Space – Pop Sci, May 1961 [popsci.com]

Project Saint [astronautix.com]

A Man-Made Moon Takes Shape, June 3, 1957 [LIFE/google books]

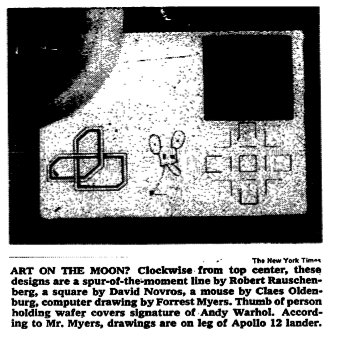

The Race To The Moon Museum

Whoa, check that out! The Moon Museum’s on the Tee Vee! Or it will be, June 21st.

The PBS show History Detectives is trying to figure out whether the Moon Museum, a SIM card-sized ceramic wafer created in 1969 by Forrest Myer, with help from an engineer at Bell Labs, which contains drawings by Myer and five other contemporary artists, actually made it to the moon.

The show uses Tampa-based curator/writer Jade Dellinger’s copy of the chip as the hook. They’re making an open plea to viewers with any info on the identity of “John F,” the Grumman engineer supposedly responsible for secretly attaching a chip to the leg of the Apollo 12 lunar landing module.

After I posted the NYTimes’ picture of the chip in 2008, it got picked up by Melissa Terras’ Blog, where several people involved in the Moon Museum came forward. The comments now hold a discussion between family members of the Bell Labs engineers who worked on the chips, including Fred Waldhauer, Burt Unger, and Robert Merkle.

Though Myers told PBS that 16 or 20 chips were made, Amy Waldhauer [whose mother Ruth Waldhauer donated the chip to MoMA which was exhibited last year at PS1’s 1969 show], said there were 40.

Also chiming in: curator Annick Berraud, who exhibited a chip in Paris last year, and who is apparently also working on an extended article on the Moon Museum for Leonardo, MIT’s arts journal.

It’s all awesome, but it also sounds like I gotta step up my game if I want to get me a Moon Museum chip. Or at least reopen the comments around here.

More Is More: Warhol’s Silver Clouds In Mies’ Crown Hall

Bell Labs’ Billy Kluver guided Andy Warhol to the Mylar balloons the artist used for Silver Clouds, his 1966 installation at Leo Castelli Gallery. And at Ferus Gallery. And at the Cincinnati Arts Center.

At the time, Bell Labs was operating both Project Echo satelloons; after Echo II’s launch in 1964 until Echo I’s disintegration on re-entry into the atmosphere in 1968, these two giant Mylar balloons were visible with the naked eye around the world.

Flash forward to this week, when the Mies van der Rohe Society opened the largest Silver Clouds installation ever, somewhere between “hundreds” of balloons and “1,000” at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s Crown Hall.

At current Armory Show prices, that’s up to $5 million worth of balloons!

ANDY WARHOL’S SILVER CLOUDS FILL S. R. CROWN HALL, through Aug. 1, 2010 [iit.edu via c-monster]

video: Warhol and Mies: Floating Silver Clouds [edwardlifson]

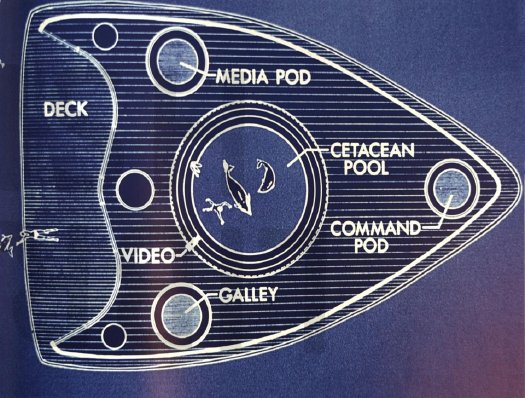

Cue The Dolphin Embassy

The architecture and art collective Ant Farm first proposed The Dolphin Embassy in Esquire magazine in 1974. When they ended up meeting the owner of the Dolphinarium in Australia a couple of years later, they worked it up into a full-fledged proposal, which got funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and a show at SFMOMA.

Basically, the idea morphed from an underwater building into an open, mobile laboratory craft [above] to facilitate human-dolphin interaction in the wild. [spatial agency has images of both early designs.] First, they would deploy the awesome power of video technology to create a common language with the dolphins. Then…

Here’s Ant Farmer Doug Michels talking about the project with Connie Lewallen in the catalogue for the 2004 retrospective at Berkeley Art Museum:

The next year and a half for me [from 1977-8] was filled with trying to make the Dolphin Embassy real. There was a lot of time spent with both captive and wild dolphins and researching dolphins, a lot of design time on the boat, and a lot of public relations time communicating the dolphin idea to Australia. Putting it in historical context, we were feeling pretty confident about accomplishing things. The House of the Century had been built, Media Burn had been done, The Eternal Frame–these large-scale productions. Cracking the dolphin communication code, well, how hard could that be?! (Laughs.)

CONNIE: Why didn’t the Dolphin Embassy get built?

DOUG: Eventually, it became clear that it was a gigantic project beyond the scale we could accomplish with the funds we had raised. While we didn’t solve cetacean communication during our mission in Australia, the Dolphin Embassy experience provided a deeper view into the mysteries of Delphic civilization.

A few months ago Andrea Grover posted this great 1976 photo of a TV-toting Michels having a diplomatic summit of some kind with his dolphin counterpart. Not sure what they discussed.

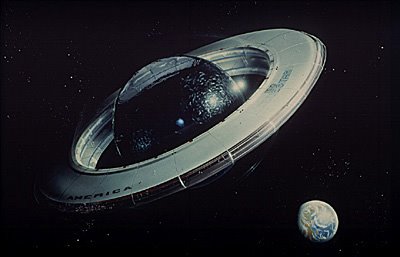

From the disbanding of Ant Farm in 1977 up until his unexpected death in 2003, Michels kept developing the Dolphin Embassy concept. By 1987, it was retitled Bluestar, a joint dolphin-human-compatible space colony with a 250-ft diameter sphere of water “ultrasonically stabilized” within a wall of space-made glass. My merely 100-ft satelloon bows in awe at the thought.

Anyway, I’m reminded of all this now because, with the iPad and all, it may be time to dust off those Dolphin Embassy blueprints.

Speak Dolphin press release at Orange Crate Art [mleddy via boingboing]

Doug Michels, Dolphin Lover [andreagrover.com]