A nice Sforzian moment in Haiti, where Fox News employee Sarah Palin recently got her hair fixed by a stylist, an unwed high school dropout teen mom, during a private tour of preacher Franklin Graham’s cholera compound.

Private except for fellow Fox News commentator Greta van Sustern, and her camera crew. And Greta’s husband John Coale, who is the DC litigator who established Palin’s PAC, and who is described as one of her closest political advisors and the top “Protector of the Palin Brand.”

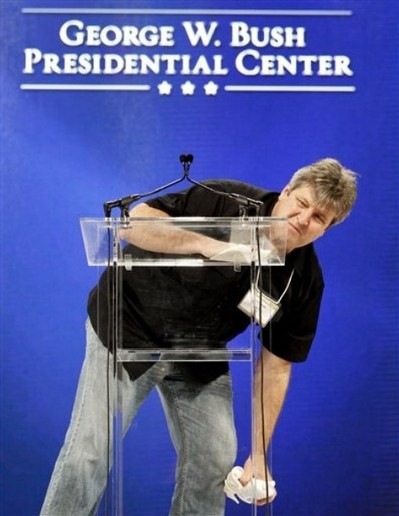

Ready for her close-up [ap images via dailymail.co.uk]

Category: scott sforza, wh producer

They Don’t Want Any Fingerprints

Sforza to the end.

The AP caption: “John Scott cleans the podium on the stage in preparation for the groundbreaking ceremony for the George W. Bush Presidential Center in Dallas, Tuesday, Nov. 16, 2010.” [daylife

Sea Force One

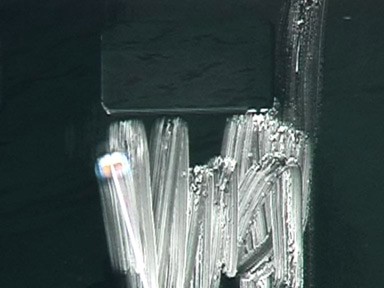

Christoph Brech is the master of the meaningful tight shot. In Sea Force One, he focuses in on a pair of workers in a small boat who are scrubbing the hull of Francois Pinault’s black yacht in front of Punta della Dogana during the 2009 Venice Biennale.

The work is included in “Portraits and Power: People, Politics & Structures,” at Strozzina in Firenze. It is interesting to compare their writeup of the piece–

We do not know who was on board the yacht – possibly François Pinault himself, the famous French luxury goods entrepreneur and primary investor in the new Venetian exhibition area. Brech has turned his camera on a moment that would otherwise have gone unnoticed, deliberately choosing not to record the sumptuous affirmation of wealth of the yacht. It is the contrast between the size of the latter and that of the small boat, or between the black hull of the yacht and the evanescent white of the soap and of the reflections upon the water, that brings out the greatness of the vessel, the actual size of which we do not grasp. The artist succeeds in moving beyond the façade of power and wealth by stopping at its surface. He seems to be suggesting that the strategy for the construction of an image of power may lie in its antirepresentation: i.e., the “myth” of power is created by veiling or concealing the identity of those who hold it.

–with the artist’s own:

The yacht Sea Force One is anchored in front of a museum at the Punta della Dogna in Venice. The waves of the lagoon are reflected in the black varnish on the ship´s hull.

From a small boat nearby, workers are cleaning the yacht.

A painting emerges from the broad, white trails of foam on the ship´s dark surface, visible only for a short while until erased by cleansing streams of water.

Once again the reflected waves dapple the yacht.

At first read, I thought Brech’s focus on the formalist, painterly abstraction was notably less political than the Florentine curators’ interpretation. And damned if it doesn’t, in fact, look like a negative inversion of a making of film shot in Franz Kline’s studio.

Which immediately reminded me of the interview Felix Gonzalez-Torres did with Rob Storr, which I’ve reprinted and referenced here several times over the years.

I’m glad that this question came up. I realize again how successful ideology is and how easy it was for me to fall into that trap, calling this socio-political art. All art and all cultural production is political.

I’ll just give you an example. When you raise the question of political or art, people immediately jump and say, Barbara Kruger, Louise Lawler, Leon Golub, Nancy Spero, those are political artists. Then who are the non-political artists, as if that was possible at this point in history? Let’s look at abstraction, and let’s consider the most successful of those political artists, Helen Frankenthaler.

Why are they the most successful political artists, even more than Kosuth, much more than Hans Haacke, much more than Nancy and Leon or Barbara Kruger? Because they don’t look political! And as we know it’s all about looking natural, it’s all about being the normative aspect of whatever segment of culture we’re dealing with, of life. That’s where someone like Frankenthaler is the most politically successful artist when it comes to the political agenda that those works entail, because she serves a very clear agenda of the Right.

For example, here is something the State Department sent to me in 1989, asking me to submit work to the Art and Embassy Program. It has this wonderful quote from George Bernard Shaw, which says, “Besides torture, art is the most persuasive weapon.” And I said I didn’t know that the State Department had given up on torture – they’re probably not giving up on torture – but they’re using both. Anyway, look at this letter, because in case you missed the point they reproduce a Franz Kline which explains very well what they want in this program. It’s a very interesting letter, because it’s so transparent.

I guess it’s the curator’s job to overexplain things [?] but Brech’s title and his discussion of the work in terms of abstraction is plenty political in itself.

The Cruel Radiance, Or What Are You People Thinking?

Remind me again where I got the idea to buy Susie Linfield’s new book, The Cruel Radiance: Photography and Political Violence?

I ordered it two weeks ago, but it just arrived yesterday, which turns out to be too long after the initial recommendation/one-click-order impulse to remember where I saw it.

At first, I assumed it was Brian Sholis’s interview with Linfield for Artforum:

I don’t urge either naive acceptance or cynical rejection of photos of political violence; the book makes a plea for us to use photographs of atrocity as starting points to engage with very complicated histories and very specific political crises. If we want to construct a politics of human rights that isn’t merely an abstraction, we need to look at these photographs of suffering, degradation, and defeat. We need to think clearly not only about the relationships among these images, how they function and what they communicate in aggregate, but about the specific conditions each one depicts, no matter how disturbing, shaming, and bewildering an experience that may be.

But it ends up I’d ordered it three days earlier.

Anyway, whoever you are, Influencer, thank you! I suspect I’m in for a grimly invigorating read.

Half-Keynesian

This is pretty damn funny. I heard somewhere that it’s unconstitutional for a president to be even half-Keynesian. I think it was Fox Business. [via andrewsullivan]

New Original Sunshine Clubhouse

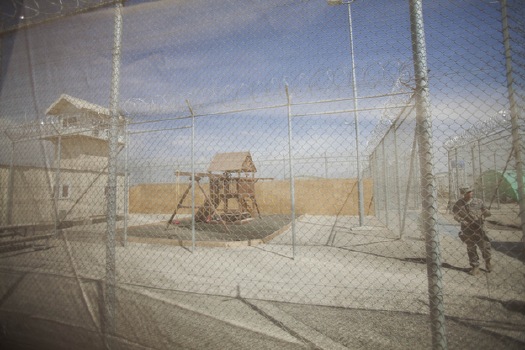

In order to prove how much less torture&abusey the new Parwan detention center is from the Bagram prison it’s replacing, US military officials let AP photographer David Guttenfelder take a picture of the new Original Sunshine Clubhouse playground at the visitors building. Like the one installed at the White House for the Obama girls, it’s made with pride in the USA by Rainbow Play Systems. I hope that’s eco-friendly recycled rubber mulch under there, too.

Meanwhile, unless this it’s some sort of retro iPhone app–which Guttenfelder has been known to use for faux-historicizing effect–it looks like the military’s photo review process involves rephotographing approved images as they are projected on a bedsheet.

Parwan prison playground by AP Photo/David Guttenfelder [charlotteobserver.com via @demilit]

Original Sunshine Clubhouse Package II [rainbowplay]

On The Set With Grenada Invasion Re-Enactors

Awesome. The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library contains several elaborate sets where visiting elementary school students re-enact the invasion of Grenada. “[I]n keeping with Mr. Reagan’s first career as an actor,” the Wall Street Journal writes, presumably without irony, “the Reagan Library appears to have the most elaborate stage sets [of any presidential library.]” The sets include an Oval Office, the White House press room, and Air Force One:

The replicas are built to three-quarters the size of the originals, and decorated as they were in 1983. The mock Oval Office has pictures of Mr. Reagan and Nancy Reagan on their wedding day, replicas of Mr. Reagan’s favorite horse sculptures and jars of jelly beans.

Also:

Making a 27-year-old invasion relevant for today’s children isn’t always easy. Kids have to be told what communists are, and why Grenada becoming a communist country would have been a big deal.

The reenactments are part history lesson, part interactive game. The kids decide whether or not to invade, how to carry out an invasion, even how to deal with media leaks.

Apparently, the re-enactment only works with elementary and middle school students. Too many high school students reject the invade-or-negotiate-with-communist-dictators script, which was written by a 25-year-old screenwriter.

At Reagan’s Presidential Library, the Kids Are in Control [wsj via @demilit]

The Togs Must Be Crazy

Colorful, cheap African textiles: they’re not just for Yinka Shonibare anymore!

Called Pagne in West Africa and Kanga [also khanga] in Tanzania, 1×1.5m screenprinted cotton wraps are produced all across Africa. There is a tradition to make commemorative kanga for major events, such as the official visit or inauguration of a US president.

Or more typically, the inauguration of a local political leader. Politicians in newly independent nations quickly adapted a traditional practice, and distributed the government-produced fabric for free or at a subsidized cost to their supporters.

As Linda reports in full-color glory on All My Eyes, the Tropen Museum in Amsterdam has a show, “Long Live The President | Portrait Cloths from Africa,” which includes over 100 examples of these textiles. Many come from the extensive private collection of Bernard Collet and can be seen online. The Tropen show runs through August 29th. Obviously, everyone should go.

Even more obviously, though, everyone should be commissioning Pagne and Kanga designers to make commemorative patterns for whatever event or non-event they want to propagandize, too. The mind reels at the awesome possibilities.

African Portrait Cloth [all my eyes]

Long Live The President | Portrait Cloths from Africa [tropenmuseum.nl via all my eyes]

Adire African Textiles [adireafricantextiles.com via a.m.e., like basically everything in this post]

Quick, Do Not Think Of Rielle Hunter

From a 1983 New York Times profile of up-and-coming artist/photographer Cindy Sherman:

One day several years ago, in the studio of David Salle, who borrows extensively from the media, Miss Sherman saw a soft-porn magazine photograph of ”a housewife looking sexy” and decided she’d try to look like that. Thus were born the ”Film Stills” with their sex objects and immaculately-packaged good girls. Miss Sherman says she was not consciously making a feminist statement when she began these pictures. ”I never thought of it as political work,” she says, ”I don’t think of myself as a very political person”…

…Maintaining full control over her ironies remains something of a problem.

Portrait Of The Photographer As A Young Artist [nyt via @briansholis]

The Washington Wives School

You start pulling on a thread, and you never quite know what starts to come out. For some great stories about the Washington Gallery for Modern Art and “The Popular Image Exhibition,” reader JA suggested, I should really check out Nina Burleigh’s 1998 book, A Very Private Woman: The Life and Unsolved Murder of Presidential Mistress Mary Meyer. So I did, and wow. No kidding. But I’ll get to that.

In addition to conducting an affair with JFK and getting killed soon after his assassination, Mary Pinchot Meyer was also one of Anne Truitt’s best friends, Kenneth Noland’s lover for a fairly extended period, and a very serious painter herself.

As Burleigh describes it, Georgetown and DC’s insular, faux-hemian postwar art community–including the members of the nascent Washington Color School–provided the havens for Meyer’s emotionally rocky life. [There are no images in the book to support it, but Burleigh repeatedly hints Meyer’s own painting was central, if not formative, in the development of the Color Field School generally, and in Ken Noland’s adoption of his signature bulls-eye specifically. Timing and other people seem to disagree with this idea, but I can’t immediately find any images of Meyer’s work. (see new post above) I’ll have to come back to this.]

New art, whether it was Abstract Expressionism in the 50s or Pop Art in the 60s, was met with criticism and suspicion from even the most politically liberal of Washington’s fundamentally conservative, power-anxious, ruling class. And art and culture were strictly gendered at a deep level almost unimaginable today–or maybe not.

A couple of brief excerpts really captured the character and challenges of Truitt’s environment in a very unfamiliar way. For me it makes her creative and career accomplishments all the more remarkable to see more of the very specific local culture in which she was working.

Often the main ties between art and power were through the wives, many of whom either sat on gallery boards or were amateur artists themselves. For at time it seemed every other wife in Georgetown was either taking painting lessons or setting herself up in a studio, though most remained firmly in the dilettante class. Presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson was linked romantically with one of the Washington women who painted, Sarita Peet, who went on to marry artist Robert gates, one of Mary [Meyers’] teachers at American University. Undersecretary of State Dean Acheson’s wife was a painter. Helen Stern, wife of lawyer Philip Stern and one of Mary’s closest friends, painted. The wife of Estes Kefauver, Nancy Pigot Kefauver, was a painter. [she was the one tapped by the Kennedys to create the Art In Embassies program. -ed.] Tony Pinchot Bradlee, Ben’s wife, eventually had her own show of sculptures. V.V. Rankine, the wife of a British speechwriter, shared studio space with Mary for a time. In a few years, Mary herself became one of the links between Washington artists and power politics.

Portraitist Marian Cannon Schlesinger, then married to Arthur Schlesinger, recalled that most Georgetowners were not all that interested in art but liked having artists in their midst to buttress their cultivated sensibility…

Marital ties between politics and the arts brought support to real artists who were struggling without money or personal connections. Having a cabinet secretary as a guest on the opening night of one’s show was all to the good. Better yet, the women’s husbands often had the money to buy the work…

Among serious artists, the capital was ruefully regarded as a backwater. New York was where they’d rather be. Washington did not provide much of a market for modern art, recalled Alice Denney, who handled the work of many of the big New York abstract artists in Washington. “I couldn’t sell a Jasper Johns then.” [p.154-5]

Whaddya know, the assistant director of the WGMA and the curator of “The Popular Image” had previously been a dealer. [Founded Jefferson Place Gallery, in fact, the Deitch Projects of its time and place.]

DC’s spirit of suspicion, amateurism and of dismissing artmaking as a wifely diversion reached a zenith/nadir in an event that sounds so much like a script for a Paul McCarthy video, I want to see it re-enacted:

By the late 1950s modern art was not regarded as subversive; rather it was just silly, or at best baffling. In 1961 the Washington wives of a group of scientists and diplomats won fifteen minutes of fame [sic] when they decided to become abstract artists during their regular bridge games. Those who took breaks from the card tables went into the kitchen and splattered canvases with kitchen items–flour, syrup, ketchup, house paint, and anything else that would stick. After a few months they showed their “paintings” to their husbands, who found them amusing, and to a few Washington galleries, who showed interest and offered to buy them. Then they broke the story to the Washington Evening Star, which covered their stunt with tongue-in-cheek glee. “An Artistic Slam,” said the headline. “Ten suburban bridge club women have pulled a fast one on modern art…Among them they have 37 children.” [p155-6]

Is it really that far off from Clement Greenberg’s description of Anne Truitt a couple of years later in Vogue?

update: Thanks to DC arts veteran and expert John Anderson for insights and corrections.

‘Little Uglies’

I’ve had a research question simmering on the back burner for a while, trying to figure out what the history of modernism and contemporary art have been in Washington DC. Partly, it was the dearth of good modernist architecture that got me wondering, then a crash course in the history of contemporary art and official Washington generally, and the odd genesis of the Hirshhorn Museum specifically. Then there was some sporadic attempts at securing Washington’s place at the art world table [more on those later].

Then last spring, I attended a dinner in the State Department’s Diplomatic Reception Rooms. Though they were originally built in an off-the-shelf, 1950s corporate modernist style that matched the building, in 1969, Walter Annenberg, Richard Nixon’s newly appointed ambassador to Great Britain, gutted the space and installed the current veneer of neo-colonial splendor. That gut job stood in nicely for the essentially anti-modernist hostility of the Washington Establishment. Little did I know.

In the the latest batch of White House documents released by the National Archives and the Nixon Library this week is an incredible 1970 memo from Nixon to his chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, outlining a direct, political assault on the NEA’s support of “the modern art and music kick,” which he he associated with “the Kennedy-Shriver crowd,” art whose supporters “are 95 percent against us anyway.”

The LA Times’ Christopher Knight has some great context and quotes, but the full document is well worth a read [pdf]. My favorite part is the postscript, which has Annenberg’s fingerprints all over it:

P.S. I also also want a check made with regard to the incredibly atrocious modern art that has been scattered around the embassies around the world…I know that [Kenneth] Keating has done some cleaning out of the Embassy in New Delhi, but I want to know what they are doing in some of the other places One of the worst, incidentally, was [career Foreign Service Officer Richard H.] Davis in Rumania.

We, of course, cannot tell the Ambassadors what kind of art they personally can have, but I found in travelling around the world that many of our Ambassadors were displaying the moder art due to the fact that they were compelled to because of some committee which once was headed up by Mrs. Kefauver and where they were loaned some of these little uglies from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At least, I want a quiet check made–not one that is going to hit the newspapers and stir up all the troops–but I simply want it understood that this Administration is going to turn away from the policy of forcing our embassies abroad or those who receive assistance from the United States at home to move in the direction of off-beat art, music, and literature.

The “little uglies” probably came from MoMA’s International Council, which, along with the DC-based Woodward Foundation, often arranged embassy art loans.

Until the creation of the committee Nixon referred to, that is. The Art in Embassies Program was started in 1964 by Nancy Kefauver, who was selected by John and Jackie Kennedy for the post. In a 1990 NY Times history of the AIEP, David Scott, who helped Kefauver get going, recalled that Washington was scorning modernism just fine before Nixon took over:

“It was at a time when we were still fighting the battle of whether modern art was seditious or evil or un-American…As a result of the McCarthy period, people were very suspicious about having any government agency deal with abstract art. If you didn’t like the art, maybe the person was a Communist.”

Digging around, I’m kind of intrigued by Michael Krenn’s 2005 book Fall-out shelters for the human spirit: American art and the Cold War, which looks at the US Government’s interactions with the private art world, primarily through the State Dept, the USIA, and the Smithsonian. From the preview:

What the government hoped to accomplish and what the art community had I mind, however, were often at odds. Intense domestic controversies resulted, particularly surrounding the promotion of modern or abstract expressionist art. Ultimately, the exhibition of American art overseas was one of the most controversial Cold War initiatives undertaken by the United States.

At $50, though, I might need a little more than a Google Book preview.

Meanwhile, poking around MoMA’s archive site to try and see what some of these ‘little uglies’ might have been, I found the 1966 exhibition, “Two Decades of American Painting 1945-1965,” organized by Waldo Rasmussen, which included 111 works by 35 postwar artists, including Gene Davis, Hans Hoffman and Jasper Johns.

It was a straight-up museum exhibit, not embassy art, but it did travel to India and Australia from Japan, and was accompanied by a film program, The Experimental Film in America, which sounds specifically designed to give Nixon an aneurysm.

And the Johns that was in the show? the a White Flag painting from 1955, which the artist held onto until 1998, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum.

Someone Left The Cranks Out In The Rain

[2022 update: the video was deleted from youtube, but the page remains in the internet archive.]

Angry crowd surrounds a fleeing Sarah Palin bus and shouts, “Sign our books!” and “Quitter!” You go to the bookstore with the mob you have, I guess, not the mob you want.

priceless angry comments on rumproast via @felixsalmon]

Finally, Sarah Palin’s Stylist Comes Out Of The Closet

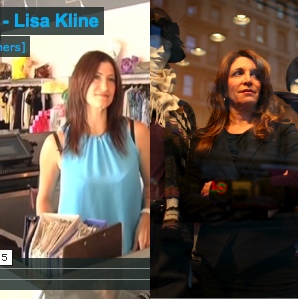

Now the truth can be told, says Lisa Kline, the New York corporate stylist who was called in on a moment’s notice over Labor Day weekend by the McCain campaign to provide clothing and hair and makeup for, first, Sarah Palin, and then her entire clan. The result: a politically damaging $150,000 designer clothing shopping spree at Neiman Marcus that clung to the giant, phony Palin ship like a noxious fart cloud until it finally ran aground on election night. Or, uh, something like that.

Now that Sarah Palin has swum to shore and is settling scores with McCain staffers and her “New York stylist” in her book, Kline has finally agreed to tell her side of the story to the NY Times.

It’s good, nostalgic reading. But the most important thing Sforza-wise is to clear up some early reporting on the story that I did here on greg.org, and possibly burnish the good name and credibility of one of my sources.

On October 22, 2008, soon after the $150,000 shopping spree story broke, I was combing through the McCain campaign’s financial filings, when I spotted both the stylist’s name, Lisa Kline, and the name of a Minneapolis baby store, Pacifier, which I recognized from my dadblogging activities. [I’d first tried to identify what kind of stroller the campaign had supposedly purchased for the prop baby Trig.]

The most prominent stylist named Lisa Kline I could find was from Los Angeles, a boutique owner who worked with Paris Hilton. I tracked down a video of her, showed it to Jon, the owner of Pacifier, and asked if he recognized her. He said he was “pretty sure” he did. It took a couple of days before I could track down LA Lisa Kline to deny her involvement.

In her Times story today, Lauren Lipton mentions this East Coast vs West Coast Kline controversy. But now that we have NY Kline’s photo [right], I think Jon’s eyewitness account bears out. Those two stylists named Lisa Kline do look an awful lot alike.

Only Her Stylist Knows for Sure [nyt]

Previously, 10/22/08: NO WAY: Did Sarah Palin Use Paris Hilton’s Stylist??

Sarah Palin’s shopping spree is so Sept. 10th

Oy. White House Sends Alma Thomas Painting Back To The Hirshhorn

I guess I can understand if the White House saw the rightwing faux-controversy over Alma Thomas’s Watusi (Hard Edge) as an unhelpful distraction, and it’s not like the country elected Obama to be curator-in-chief, but that doesn’t mean their people need to make shit up about it.

Randy Kennedy reported tonight on the NY Times’ ArtBeat blog that the painting has been returned to the Hirshhorn Museum. Watusi is well-known [at least as well-known as a painting by Alma Thomas, an African American woman in DC who only began painting abstraction and exhibiting her work after she retired from teaching, can be] as a deliberate appropriation and alteration of a late cutout painting/collage by Henri Matisse. Some critics of the Obamas ignored this history and strategy and decided the work was plagiarized and that Thomas was either a fraud or a hack.

I read the every comment on the original FreeRepublic.com thread about this controversy, and I wrote that the criticisms were grounded in longstanding conservative views on the primacy of craft and originality in the evaluation of art. In contemporary art terms, the critics of Thomas’s work rejected the pared down abstraction of both her and Matisse [without noticing or caring about the differences in technique: painting vs. collage], and they rejected the validity of appropriation as an artistic strategy [without noticing or caring about the significant differences Thomas introduced]. But it’s now obvious that this controversy is not about Alma Thomas or even about art; it’s about politics.

Which is the only explanation I can think of for why the White House misrepresented the painting’s fate:

Semonti Stephens, the deputy press secretary for Mrs. Obama, said that the painting had been intended to go in the first lady’s office and that the the decision not to put it there was made only because its dimensions did not work in the space in which it was to hang.

“This piece just didn’t fit right in the room,” Ms. Stephens said, adding that the first lady continues to admire the work of Alma Thomas and is happy to have one of her works in the White House. “There’s no other reason,” she said of the other painting. “It really has nothing to do with the work itself.”

As long as you equate “decision not to put it there” with “decision to take it down,” that statement is technically true. But the implication that the painting was not hanging in the First Lady’s office is completely false. It was, and it was there for quite some time. The office is small, and the painting is big, but it certainly seemed to fit fine until a bunch of wingnuts pitched a fit over it.

Off The Wall: White House Drops [i.e., Changes Mind] About Painting [nyt]

Previously: On Wingnuts on Alma Thomas

On Wingnuts On Alma Thomas

I guess it doesn’t matter anymore that I don’t see why the White House’s art borrowing is news now, when almost the entire list was already published and discussed four months ago [and many weeks before that, too].

Because now some wingnut Know-Nothings have taken it upon themselves to accuse Alma Thomas of plagiarizing Henri Matisse, an act which reinforces their hard-held disdain for the Obamas and anyone and anything associated with them.

It’s a false and defamatory claim, and the real story of Thomas and Matisse is deeply fascinating and diametrically opposed to the spiteful, divisive worldview in which it originated. But it didn’t seem that useful to just say so.

So I went ahead and read all 200 or so comments on the Free Republic thread where the controversy was born to see if they figured out on their own that Thomas’s 1963 painting, Watusi (Hard Edge) [top] was originally created as a deliberate reworking of Matisse’s large 1953 cutout collage, l’Escargot [above], and that it had always been recognized and discussed as such by the people who followed Thomas’s work.

By around comment #120, they’d at least decided that it was “a study,” and that Thomas wasn’t a fraud, just a hack. So a small victory for fact buried under an inflammatory and inaccurate headline.

As a hopeless art elitist and documented Obama campaign donor, there’s obviously nothing I could ever say that would persuade a hater that the Obamas’ choices of art do not, in fact, catch them out as uppity, ignorant, race-hating, affirmative actionist, communist, stalinist, Nazi frauds or whatever.

Look under the hood, though, and the substance of the angry right’s criticism of Thomas–and, often enough, frankly, of Matisse–sounds very familiar: specifically, the perceived lack of skill involved in making “modern” art; and Thomas’s lack of originality, or more precisely, the rejection of appropriation as a valid artistic strategy.