“One idea could be using mirrors so photographers could do their jobs out of the president’s sight line, the White House’s Earnest said.”

My mind is blown and I am still picking up the pieces after contemplating the possibility that White House photographers might be instructed to shoot using mirrors so as not to disrupt the president’s line of sight.

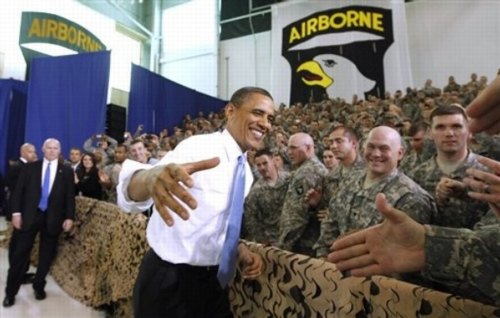

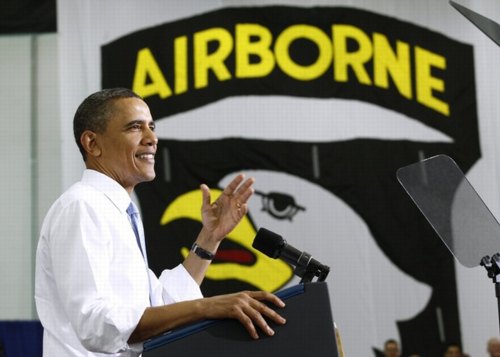

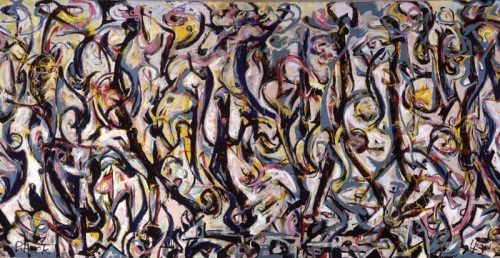

I mean, the compositional challenges pale in comparison to the artistic compositional goldmine that such an environment would provide. I mean, just imagine. Here’s one AP shot I didn’t post the other day about Sforzian backdrops at Fort Campbell. Check out how the floating reflection of the camo netting draped over the crowd barrier, which is picked up in the teleprompter:

With mirrors, photos of the president would be like rainbows, visible only from the single specific angle that aligns the lens, the mirror, and the face.

Street photographers would suddenly have an edge. Lee Friedlander, traveling with the President:

I’ve slowly been making my way through Kierran Horner’s analysis of Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Mirror in relation to Gilles Deleuze’s concept of the ‘time-image.’ I had just gotten to this part when I found the AP White House photo policy story:

Left alone, Alexei locates and sits in front of a large mirror hung on the wall. The next shot begins stationary behind Alexei, facing his reflection in the mirror, and the camera slowly pans in over his shoulder, focusing ever more tightly on his reflection, until, gradually, the reflection becomes the sole image of the frame, staring back toward the actual Alexei.

There is then a sharp cut to reveal a medium close-up of Alexei sat contemplating his reflection from the opposite angle. This shot/reverse shot dynamic and the ‘eye-line match’ are common to most conventional cinema, establishing an object, or person, as perceived by a character from their point of view.

As David Bordwell and Kristin Thompson describe it ‘shot A presents someone looking at something off-screen shot B shows us what is being looked at’ (2004: 303). However, as in this case, the ‘eye-line match’ refers conversely to an interaction between two characters, here, the actual Alexei and his virtual counterpart. It is as if he is reacting to/with his reflection. This dialectic can be read as representing the Deleuzian ‘crystal-image’:

‘In Bergsonian terms, the real object is reflected in a mirror-image as in the virtual object which, from its side and simultaneously, envelops or reflects the real: there is a ‘coalescence’ between the two. There is a formation of an image with two sides, actual and virtual. It is as if an image in a mirror, a photo or a postcard came to life, assumed independence and passed into the actual, even if this meant that the actual image returned into the mirror and resumed its place in the postcard or photo, following a double movement of liberation and capture.’ (Deleuze 2005b: 66-67)

I see Barack Obama as Alexei. And a virtual presidency. Can you begin to imagine what kinds of images this would produce? Forget the stunning conceptual aspects for a minute; has anyone at the White House thought through the political implications–should we call them the optics?–of not permitting the cameras’ eyes to gaze upon the President directly?

Maybe not mirrors, then, but what about one-way mirrors? Is that what they’re thinking? Put the photgraphers on the darkened side of a one-way mirror. Fortunately, there’s only 225 hours of Law & Order-related programming on basic cable each week to communicate the absolute trustworthiness of anyone speaking on the mirrored side of the glass.

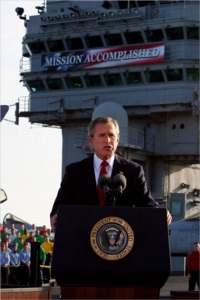

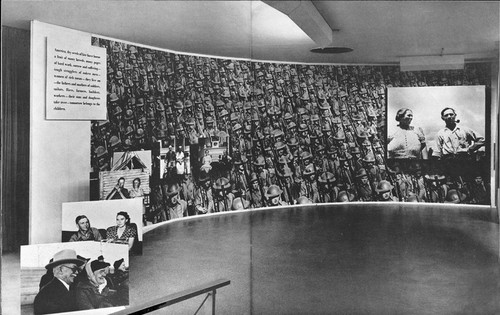

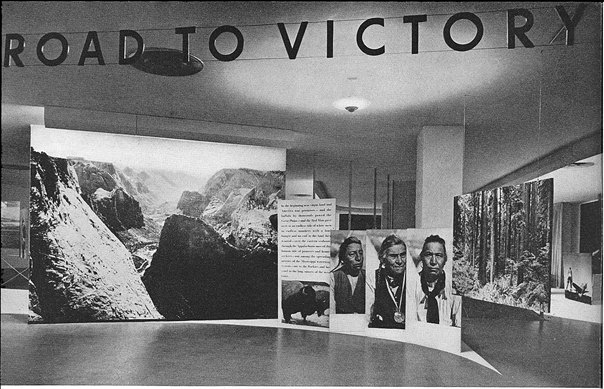

Before getting too fixated on the complications of presidential imagemaking, though, it’s worth remembering that the White House is already a supremely weird place for photographers to work. Go back to 2009, just days after President Obama’s inauguration, when the NY Times’ Stephen Crowley pulled back the curtain on the surreal and utterly staged 12-second tradition known as the “pool spray.” These are the images whose authenticity is suddenly, apparently, of such great concern.

Previously: WH beat photogs upset at staged photographs they don’t take