Ausgezeichnet, this is so awesome.

Amidst a fierce, ongoing, politicized debate, Google has released the first Street View panoramas for Germany. To assuage privacy concerns, the company is allowing homeowners to assert their Verpixelungsrecht, that is, their Right to Pixelation.

Some 240,000 locations are thus set to be blurred out. From what I can understand, though, the rollout is still in its early stages, and so only a handful of blurred buildings have gone live.

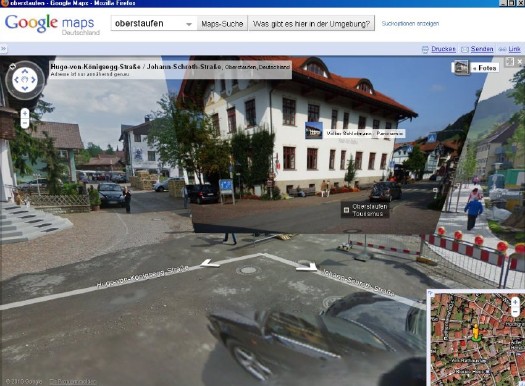

And the hunt is on. The few opt-out houses spotted so far have fed the media firestorm anew, and the examples cited by Der Speigel or FAZ [Google Translate] from Oberstaufen, the tourist village which first invited Street View to town, have been removed by Google “for review.”

At the center of the debate is my old blogging 1.0 buddy Jeff Jarvis, whose rather hyperbolic post on the subject, “Germany, what have you done?” was translated and republished by FAZ. [thanks greg.org reader/cinematographer Sanne Kurz, who tweeted about Jeff’s column.]

Sanne had referenced Germany’s complicated history of a giant state surveillance apparatus that elisted millions of citizens to spy on each other. Jeff’s having none of it:

This is not a matter of privacy. And don’t tell me it has a damned thing to do with the Nazis and Stasi; that’s patently absurd. If anything, the Stasi would have exercised their Verpixelungsrecht to obscure their buildings from public view, taking advantage of the cloak of secrecy the idea provides. That’s the danger of this.

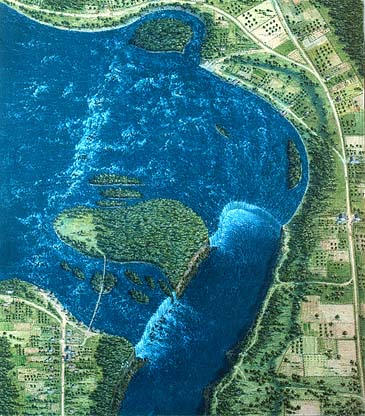

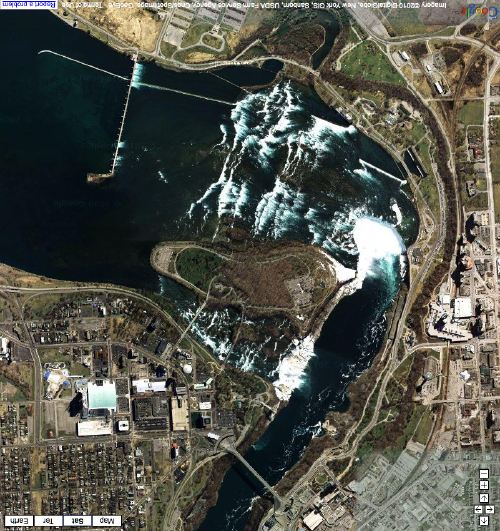

Well, who’s Stasi now, because that is exactly what is happening next door in the Netherlands, where the Intelligence and Defense Ministries actively distort the Google Maps imagery and block Street View access for dozens of sites they have unilaterally deemed sensitive. [Search greg.org for “Dutch Camo” for details, such as they are.]

While obscuring active military bases or the royal palaces may be justified for security reasons, the Dutch government’s Google Maps pixelation program also renders maps of entire villages and town centers unusable as it hides abandoned NATO weather stations–or nothing at all.

The state needs to be held accountable in its efforts at information control and censorship, but I can’t disagree more strongly with Jarvis’s unnecessarily extreme, incendiary language to criticize the individual assertion of some control over his own data. Referencing the Street View pano above:

Ugly, isn’t it? As someone in the audience said when I spoke on the topic at a meeting of the Green party in Berlin a few weeks ago, it is as if they are digitally bombing the German landscape.

Actually, no it isn’t, and–holy crap, wtf?–no it isn’t.

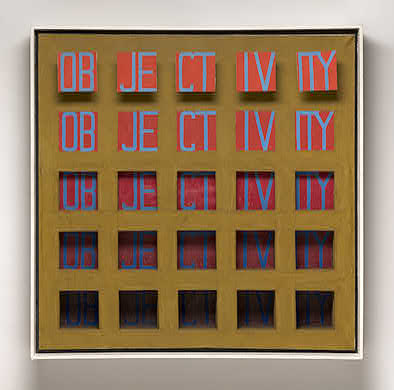

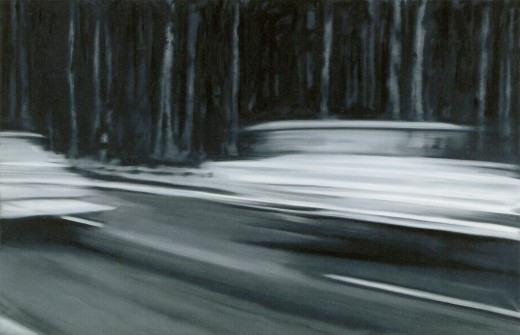

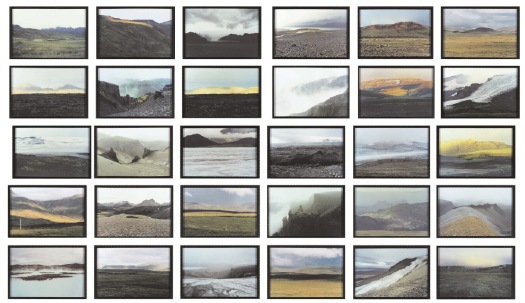

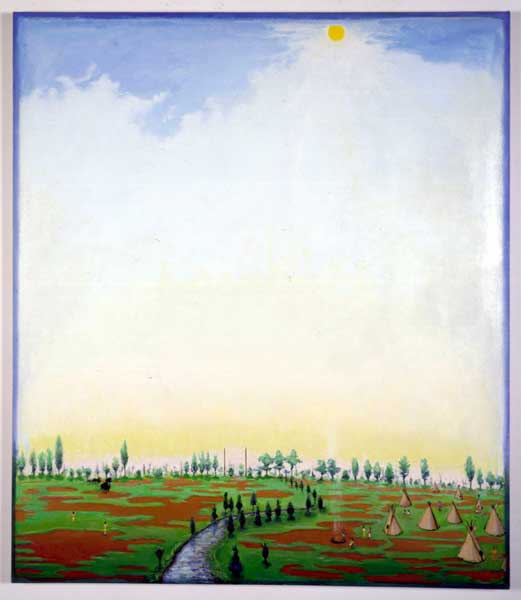

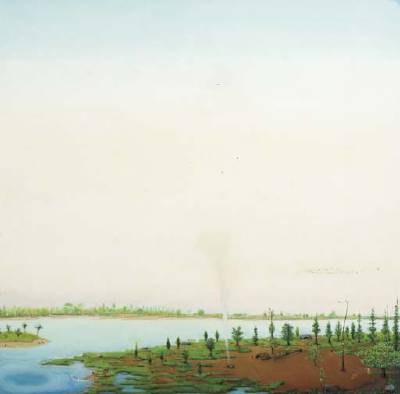

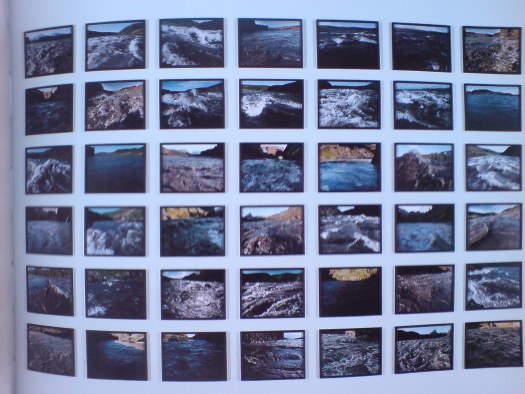

Google’s German Street View blurring looks utterly fantastic. And for that matter, fantastically German. By which I mean, of course, that it looks like a Gerhard Richter painting.

Nurses, 1965, image: gerhard-richter.com

Richter’s signature blurring technique calls into question the status, context, and veracity of the photographs that are his source material. Richter, Rosemary Hawker has argued,

refers not to the visual plenitude and truth that we usually associate with photography, but rather to its moments of representational inadequacy, to photographic blur and lack of focus that results in deliberately obscured imagery.

It’s worth noting that Richter began his blurred photo-painting series soon after fleeing East Germany.

I would think that the persistence of a few deliberately obscured images on Google Street View will serve as a useful corrective to the convenient, info-rich panorama’s seductive call, and will help remind users that they are, in fact, not in “the German Landscape,” but in a corporately controlled, commercial, and contested simulacrum of it.

Two Fiats, 1964, via gerhard-richter.com

Far from “bombing” the supposed digital public sphere, the people who exercise their Verpixelungsrecht are asserting the individual’s right to virtual protest, to engage the digitization of his entire world on his own terms.

Mustang Squadron, 1964, image: gerhard-richter.com

Google has filed for patents to place advertising, “virtual billboards,” within Street View, reserving for itself the right to control and alter its ostensibly objective representation of the world for its own reasons, including, but not limited to, its own commercial gain. If someone painted their URL on the front of their store, would there be an outcry if Google threatened to blur it out unless they got a piece of the action?

Jeff argues that it’s folly for politicians to restrict innovation like geo-tagged facial recognition that, who knows, might be useful in locating Katrina victims. But who’s to say that, when our reality gets augmented to death with advertising and tracking, opt-out blurring isn’t where the real value will be? It’s the unlisted number of the future.

Or the vanity phone number. As an inadvertent-but-eager connoisseur of Google Map pixelation techniques, I could just as easily envision a premium Street View image management business emerging out of this controversy. In fact, it’s already started.

Just look at the unsightly street closure and construction project right in front of the Tourism Office of the otherwise-scenic Oberstaufen. Sheesh, no wonder they baked Street View a cake. Now check out the screenshot Spiegel got, where an embedded photograph from Panoramio helps clean things right up, mostly:

The Street View we see now is a mere shadow of the virtual world–or the virtualized real world–to come, and I’d like to think that when it comes to building and designing that world, digital citizens will be able to vote with more than their wallets.

At the very least, when people start paying Google to decorate their Street View houses with Blingee crap and animated gifs, mark my words: we’ll be grateful for the visual respite these Richterian Street View sites will provide.

Related, actually from over a year ago: Gerhard Street View

When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered

When we last considered the techno-militartistic merits of pre-WWII era sound location devices, I wondered