I was looking around for something on Richard Hamilton this morning, when I Googled across a 2010 discussion between the artist and the human rights architect Eyal Weizman at Map Marathon, one of the Serpentine Gallery’s Marathon series. It was rather compelling for several reasons.

For one thing, their discussion of the political power of maps was frank and vivid in a way that I’m unaccustomed to in US media or art world forums. They talked specifically of Palestine & Israel, but I quickly took down two quotes that seemed very relevant to, of all things, Google:

the “double crime of colonialism is to colonize and to erase its own tracks” -Eyal Weizman paraphrasing Edward Said.

“All maps of a political kind have nothing to do with the people who occupy the territory being mapped.” -Richard Hamilton.

These both reminded me of Google Maps’ tendency I find so eerie, of Street View cameras and car/trikes to be erased from the panoramas. It turned out at the same time of Map Marathon, I had been working on this Walking Man project, where I followed the Google Trike through The Hague, its European debut, and collected the disembodied portrait fragments of the guy–who turned out to be a Google employee–walking alongside the entire trip.

It would have seemed a bit extreme at the time, but now it feels depressingly plausible, even urgent, to consider Google and its pervasive data collection as a political force and as a surveillance agent. Whatever the benefits of Google Maps–and they are real–we are still in the dark about just how transparent our information is, and how opaque the implications of Google’s deep information structure is. And we won’t know, and we won’t have open, informed debates and political discussion of it until our entire cultural landscape has been transformed by the company. And maybe not even then.

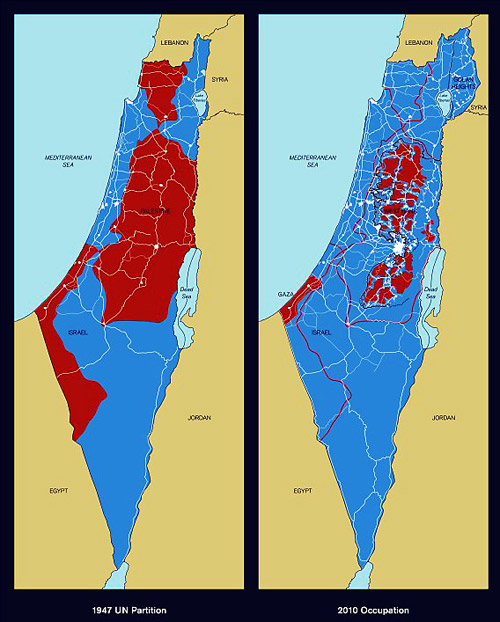

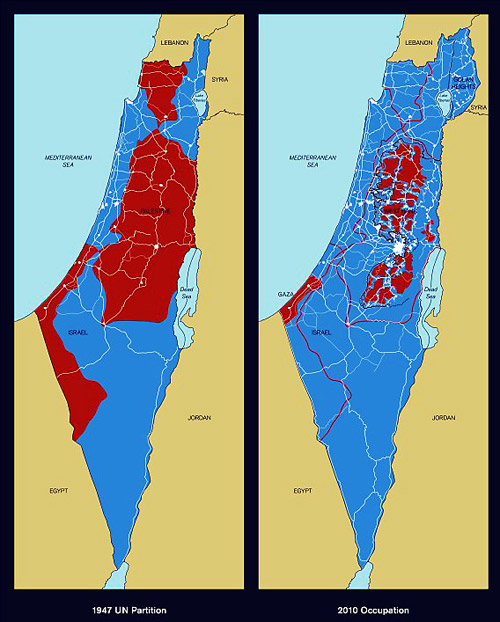

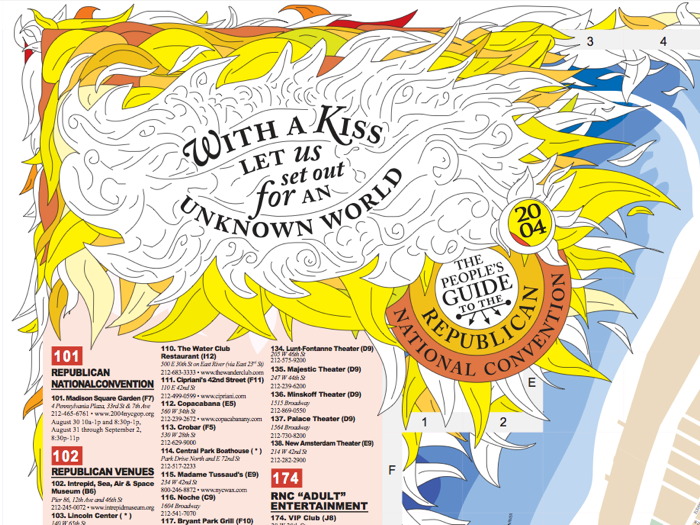

Richard Hamilton,Maps of Palestine, 2010

So this is what’s going through my head as Hamilton and Weizman discuss the artist’s contribution to the show, Maps of Palestine (2010), above. It was a pair of maps from 1947, and 2010, showing the shifts in political control between Israel and Palestine. It basically shows the impact of Israeli military retaliation in 1967 and subsequent settlement activity in occupied territory, and it appears to challenge the practicality of a two-state solution. [Indeed Weizman, upon whose groundbreaking crowdsourced mapping and analysis the newer map is based, believes only a one-state solution is feasible now, and that everyone’s just going to have to figure out how to get along. That’s a dark optimism of a sort, I guess.]

And then I start wondering, what, exactly, are these maps like? I mean, what did Hamilton actually make and show? Unsurprisingly, almost no one seemed able to talk about the maps as images or as objects; some people called them/it paintings, but nearly all the discussion was around their content and its meaning. Adrian Searle wrote about the Maps in The Guardian in the context of Hamilton’s art historical career and extensive political engagement. When a 4-map variation of Maps of Palestine was included in 4th Moscow Biennale, not only was there no image, or dimensions, the title and the very subject have been omitted. In the opening’s press announcement, director Peter Weibel stated, rather amazingly,

There will be quite a few so-called political works at the exhibition. For example, Gerhard Richter’s painting is not just a painting, it also refers to 09/11, and the piece by Richard Hamilton does not just show us a map of Israel, but it asks us questions about war.

Credit lines are a continuation of occupation by other means.

Maps of Palestine, 2011, 4th Moscow Biennale

see full-size img in Al-Madani’s flickr stream

The only image I can find online of the Moscow Maps is from flickr user Al-Madani, and it’s the first to show the work as a physical object. It curls up on the lower corners: an unmounted print of some kind.

It’s only after turning up Rachel Cooke’s interview with Hamilton in advance of his Serpentine show, “Modern Moral Matters,” which coincided with the Map Marathon, that I get my answer. Cooke’s entire anecdote is kind of golden, though:

Hamilton hands me a colour copy of a piece of new work that will hang at the Serpentine. It is a political piece, and consists of two maps: one of Israel/Palestine in 1947, one of Israel/Palestine in 2010, the point being that, in the second map, Palestine has shrunk to the size of a cornflake. I hold the image in my hands, and give it the attention befitting a new work by an artist of Hamilton’s reputation. In other words, I look at it very closely, and I notice something: on these maps Israel has been spelt ‘Isreal’. Slowly, my cogs turn. Hamilton loves wordplay. One of my favourite pieces of his is a certain iconic French ashtray subtly tweaked so that it says, not “Ricard”, but “Richard”. So presumably this, too, is a pun. But what does it mean? Is-real? Hmm. This must be a comment on the country’s controversial birth. Either that, or he wishes to suggest that the Israel-Palestine conflict is a nightmare – can it be real? – from which we will one day wake up. How clever.

“So what are you up to here?” I ask. “Why have you spelled Israel like this?”

Hamilton peers first at me then at the image. “How is it spelled?” he asks. I tell him how the word should be spelled and how he has spelled it.

There is a small silence. “Oh, dear,” says Hamilton. Rita Donagh gets up from her seat and comes round to look at the image over my shoulder. “Oh, dear,” she says. The misspelling is, it seems, just that: a mistake. It’s my turn now. “Oh, dear,” I say. “I’m so … sorry.” My cheeks are hot. Hamilton looks crestfallen. Donagh looks worried. “Can you change it?” I say, thinking that Hamilton works a lot with computers these days. “Not very easily,” he says. Oh, God. On the nerve-wracking eve of his new, big show, I have just told the 88-year old father of pop art that there is a mistake in one of his prints (this one is an inkjet solvent print). Why? Why did I do this? And how on earth will our conversation recover?

After a moment of perplexity, though, Hamilton starts to laugh. “Oh, well!” he says. “I’m sure there’s some way of sorting it out. Not to worry!”

So there we have it. Inkjet print. And from the image published above, it appears they reprinted it with the correct spelling. If only all the Israeli-Palestinian mapping problems could be resolved so quickly.

Also, I wonder if these maps will turn up in Hamilton’s Tate retrospective next month. UPDATE: YES IT WILL. [thanks to Tate Modern’s curators and communications folks for the update]

Map Marathon: Richard Hamilton & Eyal Weizman – Political Plastic [vimeo]

Map Marathon – 2010 [serpentinegalleries.org]

Modern Moral Matters | Richard Hamilton [serpentinegallery.org]

Richard Hamilton: A masterclass from the father of pop art [theguardian]

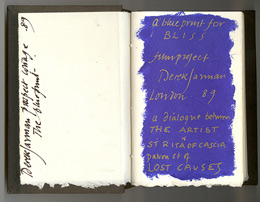

When Blue was still called Bliss, back in 1987, and was a Klein-related companion film to The Last of England, Jarman filled a notebook with dialogue, poems, and IKB monochrome paintings. The Bliss Book and other Blue-related preparatory and archival material will be in

When Blue was still called Bliss, back in 1987, and was a Klein-related companion film to The Last of England, Jarman filled a notebook with dialogue, poems, and IKB monochrome paintings. The Bliss Book and other Blue-related preparatory and archival material will be in