Our oldest had to read Mansfield Park in 9th grade and very much did not like it, and so I’ve avoided it. Until I heard poet Dionne Brand talking about it with David Naimon on the Tin House podcast, Between The Covers. [youtube] Brand’s latest book, Salvage: Readings From The Wreck, is a forensic return to a whole host of “classic” texts, including Austen’s Mansfield Park, that find Blackness where it has been omitted by the structures of colonialism, imperialism, and slavery. But Brand goes beyond literary analysis to question the function of a novel, and how forms of writing—and thus thinking—perpetuate and protect the structures that spawned them.

Anyway, now I just read another conversation between Brand and Saidiya Hartman, from Bomb Magazine last fall. Here they discuss the larger goal outlined in Salvage:

[Dionne Brand] I’m rereading these texts with the hope of abandoning them as aesthetic objects. When these texts were written, they were done so self-consciously as colonial objects. If they were being made as aesthetic objects, they were for the European bourgeoisie. In fact, these texts were created and encouraged because they told readers about the wonderful life that slave-owning, the eradication of Indigenous peoples, and violence allowed.

[Saidiya Hartman] I really like that formulation: to reread these texts with the hope of abandoning them as aesthetic objects. Salvage clearly articulates the ways in which a colonial project, a settler project, even when it does not announce itself explicitly and politically, finds refuge in the categories of the aesthetic and the beautiful.

Even if I hadn’t heard Brand’s conversation, I like to think I’d have spotted the glaring anxieties of capitalism that obsess almost every character in Mansfield Park, as well as the many references to Antigua and, thus, the direct dependence on plantation slavery of the family’s fortunes—and their entire world. I’m only halfway through, and this book [Austen obv] is grim as hell.

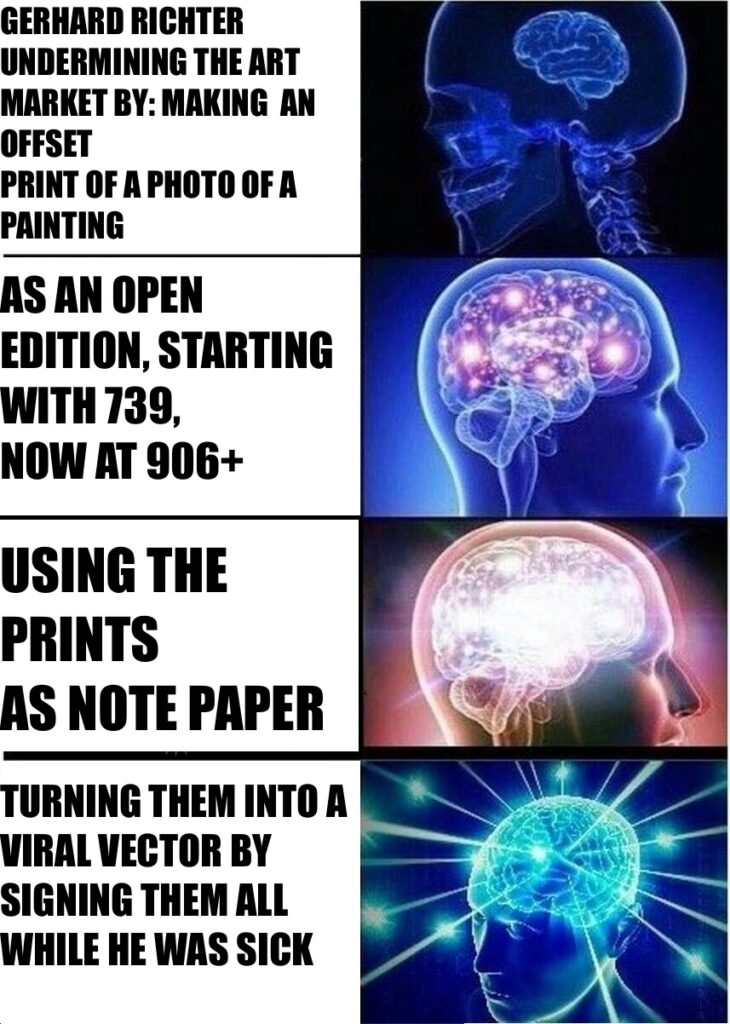

Brand’s not through, though. Her and Hartman’s discussion of photography, visual art, aesthetics, and beauty continues to work away in my mind.

[meanwhile, in case you needed any evidence that this conversation happened in September: “Soon that phrase will be outlawed in the States. (laughter)“

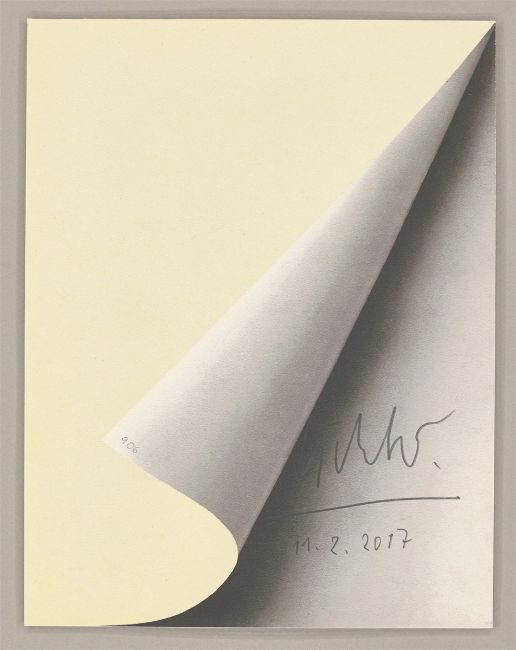

Dionne Brand: Salvage: Readings From The Wreck [tinhouse]

Dionne Brand interviewed by Saidiya Hartman [bombmagazine]