Flipping through the lots for Christie’s upcoming contemporary sale feels like diving into the greg.org archives. Besides the Rauschenberg combine coming out of the Ganz’s closet, there’s also:

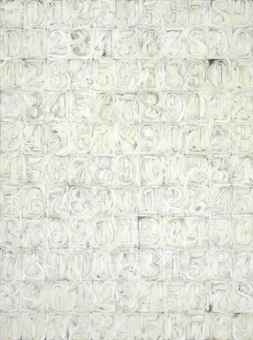

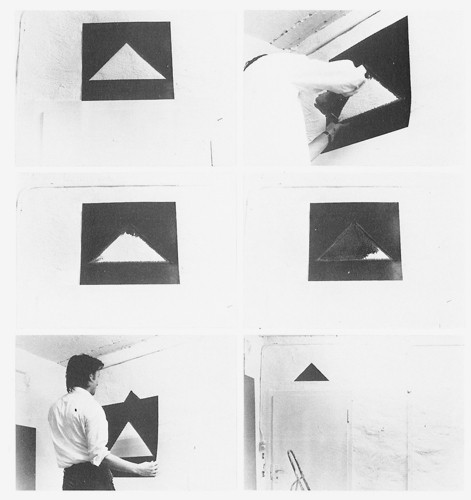

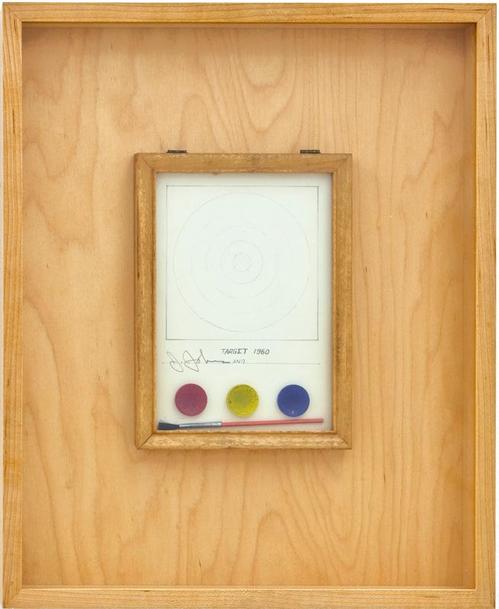

a great Johns White Numbers painting (1991) by Sturtevant. This text is nice, too:

To create her paintings, Sturtevant does not copy. She does not employ grids, squares, tracing paper or cameras. She summons her memory of images to recreate and reinvent them. By obsessively utilizing the identical materials and techniques as those who came before her, Sturtevant asserts her work is not about copying or appropriation, rather, the power and autonomy of originality.

Love that, so Pierre Menard.

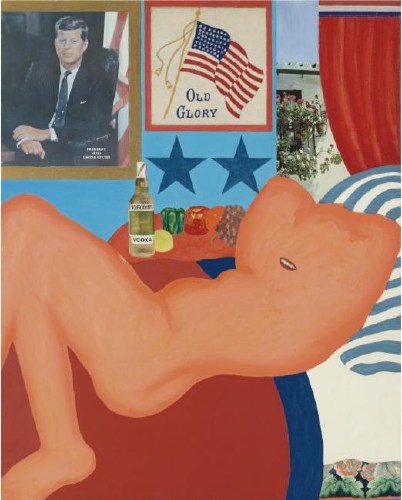

Tom Wesselmann’s Great American Nude #21 (1961) is up for sale again, too. In her biography of DC artist and JFK mistress Mary Pinchot Meyer, author Nina Burleigh mixed up #21 with #44. It was the former, not the latter, which was the subject of some controversy in Washington when it got yanked before the opening of the 1963 Gallery of Modern Art exhibit, “The Popular Image.” Burleigh said Meyer whispered about it to JFK, who laughed and kept it in. The painting in the show. But I looked it up, and no. The painting stayed out, probably because it included a nude next to an image of the sitting president. Or something. Anyway, censorship! Scandal! Sale!

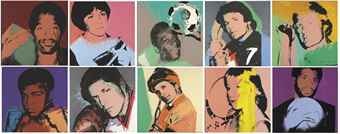

And speaking of scandal and mystery, Los Angeles collector Richard Weisman is apparently selling one of his remaining sets of Warhol Athlete Series paintings, which he commissioned en masse back in the day.

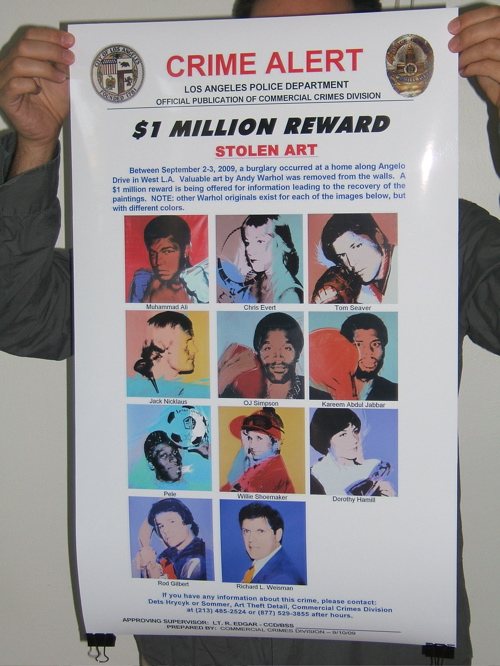

They’re like the set that was reported stolen from his dining room a couple of years ago. The disappearance of which prompted LAPD’s art theft unit to release the awesomest wanted poster ever. Which I tried to Kickstart into production as the Find The Warhols Project, only Kickstarter and I had apparently not developed our audiences sufficiently to accept the idea of a project-as-critique. And the reward for which was discontinued anyway when Weisman decided to drop his insurance claim, because of the investigative hassle. Which art theft experts read as a sign that the theft was an interfamily job, and not the kind of thing that one likes to have reported out in all the papers if one can help it.

But it’s not that set; I checked. Instead, it’s the set Weisman tried to sell in China during the Olympics for $28 million. Now priced to move, with an estimate of just $4-6 million. Also, too bad the Warhols don’t need finding anymore; that poster looks really sweet. Guess I’ll save it for the retrospective.

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The

Christie’s is selling The Tower, a 1957 combine by Robert Rauschenberg which Victor and Sally Ganz bought from Betty Parsons in 1976. The work is a double portrait assembled from found, painted objects and light bulbs, and was originally part of the set for a Paul Taylor Dance Company production based on the myth of Adonis. The

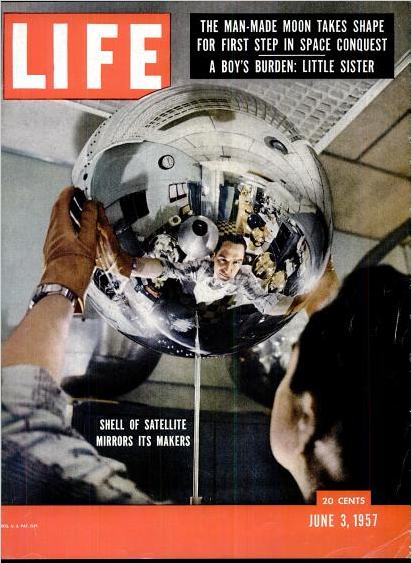

Everyone [sic] probably has the story tucked away in their head that science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke was the

Everyone [sic] probably has the story tucked away in their head that science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke was the