Sperone Westwater calls it Light Ballet on Wheels, 1965. Sure.

It’s hard to tell from the microfilm, but a photospread of artist-made household objects in the New York Times Magazine [“They Call It Art,” (-ouch), Sept. 25, 1966] sure mentions that “15. Black metal drum table by Otto Piene has a glass top and a base that projects light patterns on the ceiling. From Howard Wise.” Just wonderin’.

Author: greg

Otto Piene’s Light Ballets & Exhibiting In The Sky

Following on to their 2008 retrospective of ZERO, Sperone Westwater is exhibiting work by the group’s co-founder, Otto Piene. ” Otto Piene: Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967″ runs through May 22nd. [16 Miles has very nice installation shots.]

While I am stoked to see Lichtballet, 1961, above, the piece I’d most like to see, the silver sphere hanging on the right, is not in this show. This photo, by Günter Thorn, turns out to be of Lichtraum [obviously] from “Bilder, Objekte, Grafiken und Lichtraum,” an exhibition last winter at the Kunstverein Langenfeld.

Last year, the Pompidou had a cheeky, brilliant exhibition, Voids: A Retrospective, which consisted of nine empty galleries, each a different re-creation of an artist’s showing of a void. [John Perrault discussed the show at length in March 2009.] I feel I am now tiptoeing backwards into a similar project, a retrospective of artists’ shiny silver balls.

Piene was creating these Light Ballet pieces while the Echo I satelloon was orbiting the earth, its reflection visible to the naked eye. He exhibited them in New York in November 1965, at the Howard Wise Gallery. Sperone has reprinted Piene’s essay from the small catalogue to that show. Here is an excerpt:

In 1959 I played the light ballet with hand lamps, in 1960 I built the first machines, in 1961 they appeared in large darkened rooms at exhibits and in museums: one object, two objects in a large hall, a waste of space, an elimination of conventional attitudes about quantity. The farther the distance between the projecting device and the light-catching confines of a room, the larger are the light forms. And when they are large, the claustrophobia caused by the ordinary cubicity of our interior spaces recedes.

…

My endeavor is twofold: to demonstrate that light is a source of life which has to be constantly rediscovered, and to show expansion as a phenomenal event. Everything is striving for larger space. We want to reach the sky. We want to exhibit in the sky, not in order to establish there a new art world, but rather to enter new space peacefully–that is, freely, playfully and actively, not as slaves of war technology.

A rubber skin, helium and the wind, light, electricity and fireworks seem to me excellent media. The revolving beam of a lighthouse and a balloon in the air are more convincing sculptures than the big chunks that are so hard to move. Calder’s mobiles can be taken apart. Our objects ought to be inflated or ignited or projected. And environments? As far as a laser beam reaches. Are the jet pilots who write vapor trails in the sky the artists of our time, as Gothic stone-masons were the artists of theirs?

Despite their similar shapes, there is one essential difference between Gothic cathedrals and rockets: a cathedral seems to soar, expressing the yearning of its builders to ascend to heaven; a rocket does soar. The same technical difference exists between traditional sculpture and my objects. Previously paintings and sculptures seemed to glow, today they do glow, they are active, they give, they do not merely attract the eyes, they do not merely express something, they are something. A filament glows and warms, a painted halo only reflects light. Energy in a contemporary form produces the living media. Is the filament in itself a piece of art?

Transformation still has two meanings, one technical, one spiritual. He who leaves his house leaves the light on to make it appear inhabited.

Previously: Otto Piene et al’s Centerbeam & Icarus on The National Mall

The Name Is Dumas

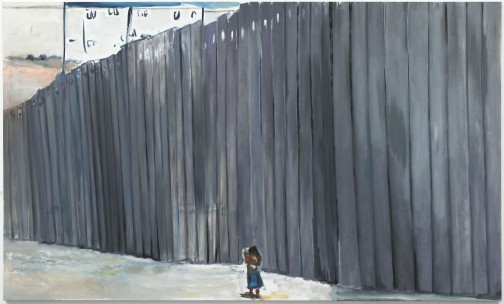

Figure in Landscape, 2009

I’m probably enjoying reading the legal filings in Craig Robins’ lawsuit against David Zwirner a little too much. [Randy Kennedy’s got a nice summary in the NYT today; basically, Robins says Zwirner revealed a confidential sale of a Marlene Dumas painting, which landed the collector on the artist’s blacklist, which Zwirner said he’d fix and didn’t, and that Robins could choose some Dumases from the current show, which he couldn’t.]

I’ve got no horse in this race, and I’m not a fan of Marlene Dumas’s work. [Though I admit it’s hard to consider it separate from the uncritical adulation that accompanied the outsized market hype of the last few years. And I did find some of these new paintings–including the three Robins said he wanted to choose from–admirably Tuyman-esque.]

What I am is fascinated by the language and the assumptions of collecting [and buying and selling] art that underpin it. The overly precise, legalistic argumentation of the filings reveals just how dependent many of the art world’s core interactions are on elision, subjectivity, and intentional ambiguity.

First, from the amended/updated version of Robins’ original complaint:

First, from the amended/updated version of Robins’ original complaint:

10. Thereafter in early 2005, defendants [i.e., Zwirner] breached Agreement I [i.e., the confidential sale a couple of months earlier in October 2004] by disclosing to MD that plaintiff [Robins] had in fact sold “Reinhardt’s Daughter,” [right] which defendants ultimate, apologetically and unequivocally admitted when plaintiff called defendants out on the issue. MD then immediately placed plaintiff on her personal “blacklist”, i.e., that plaintiff would not be able to buy any MD artwork in the Primary Market. Plaintiff’s placement on MD’s blacklist was and is a direct result of defendants breach of the confidentiality of Agreement I. [p.4, emphasis added to signal points of amusement]

This is clearly, awesomely Dumas herself. Zwirner had no need to “call Robins out” on the sale; he was a party to it. So at some point, within weeks or months of the deal, Dumas confronted Robins about secretly selling her work. His unequivocal apologies notwithstanding, he landed himself on “her” blacklist.

But Dumas is not actually named in the lawsuit, only Zwirner [and his galleries/legal entities.] So the artist herself is not a “defendant,” but the language of the complaint seems to indicate that at one point, Robins considered making her one. So while he sold work secretly through another dealer not the artist’s, and then abjectly–and, it turns out, unsuccessfully–apologized when she called him out, at some point in the last few weeks between drafting his lawsuit and filing it, Robins came to appreciate that suing an artist for blacklisting him was probably not the most effective way to get off her blacklist. I would count this as progress.

Alcoa Forecast: Spheres Of Tomorrow

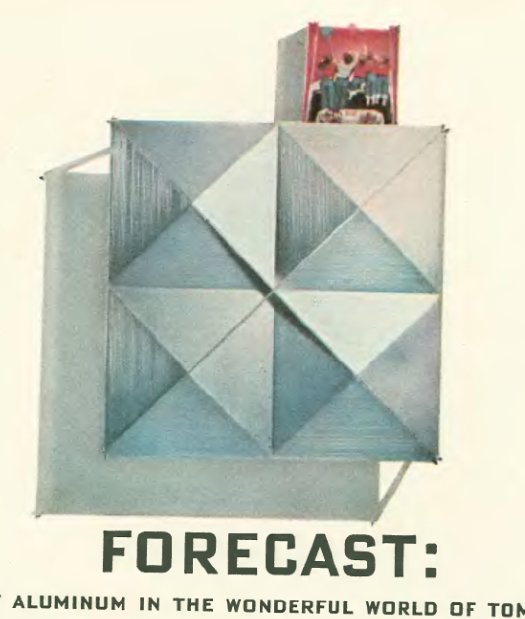

They’re both under-known, and so they probably deserve their own posts, but the uncanny similarity of these two Alcoa Forecast program designs requires me to put them together.

Greta Magnusson Grossman was a Los Angeles-based Swedish industrial designer. According to the notes at the 2008 Drawing Center exhibition of her never-before-seen technical drawings, she was highly influential on her fellow Southern California colleagues in the 1950s-60s, including the Eameses.

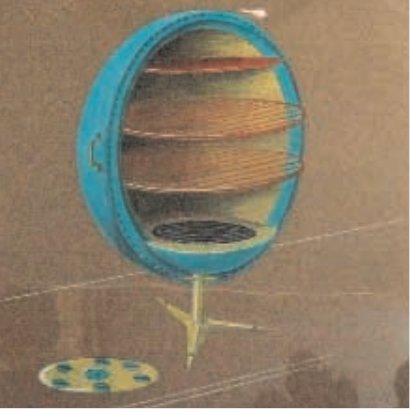

That show included a sketch [above] for the personal aluminum oven she designed for Forecast. A small photo of the wacky, ball-shaped oven appeared in a collaged Forecast ad in the Dec. 28, 1959 issue of LIFE Magazine.

[update: whaddyaknow, the new blog The Modernlist reports that the Arkiteturmuseet in Stockholm has the first-ever Magnusson Grossman retrospective right now, through May 16. Definitely check out that crazy Grossman House.]

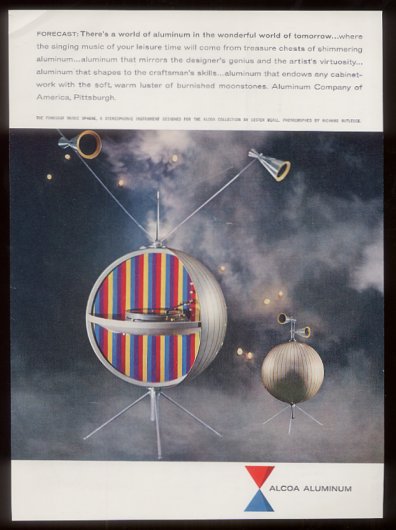

Graphic designer Lester Beall, meanwhile, is better known, at least by my criteria: I recognize his awesome, constructivist-style photocollage posters for the Rural Electrification Administration from MoMA’s design collection. His portfolio site says he designed the Music Sphere for Alcoa in 1956, which seems remarkably early.

An unsourced tear sheet for a Forecast Collection ad on eBay says it’s from 1969, which is remarkably late. I’m going to guess it’s really 1959. But the real question is why the future doesn’t have even a tiny fraction of the giant, shiny aluminum ball-shaped appliances we were promised?

“Aluminum that mirrors the designer’s genius and the artist’s virtuosity”? “Aluminum that endows any cabinetwork with the soft, warm luster of burnished moonstones”?? I think we have found Project Echo’s official stereo!

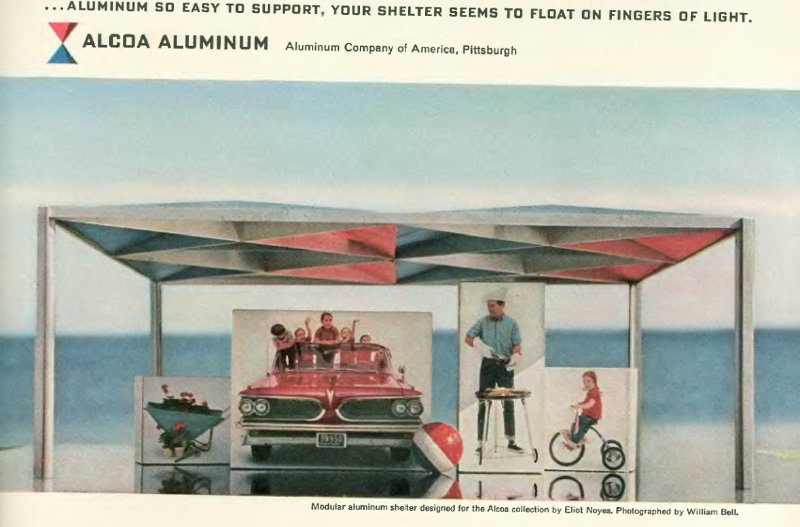

Alcoa Forecast: Eliot Noyes’s Wonderful Aluminum World Of Tomorrow

I’ve been digging back through the New Yorker magazine archive, looking for ads from Alcoa’s Forecast Collection campaign. That’s the one, if you will remember, for which Ray and Charles Eames created the Solar Do-Nothing Machine [which has since completely disappeared, but which I will one day bring back.]

What a fantastic campaign it’s turning out to have been: beautiful objects and concepts created to brand aluminum as the material of America’s glorious consumer future. It’s like a virtual world’s fair pavilion, fabricated [almost] entirely out of marketing. And all executed by a slate of top drawer artists, designers and photographers. And somehow, almost completely invisible now.

So far, I haven’t been able to find any thorough or systematic treatment of Alcoa’s Forecast program, so let me put a couple of great-looking things into the mix:

From a July 25, 1959 ad, here’s a modular aluminum shelter designed by Eliot Noyes, and photographed by William Bell. Unlike the Eameses and Isamu Noguchi’s Prismatic Table, which were both executed as life-size prototypes, it looks like Noyes’s Forecast contribution never made it past the maquette stage. I expect to see this referenced in the next Urs Fischer catalogue.

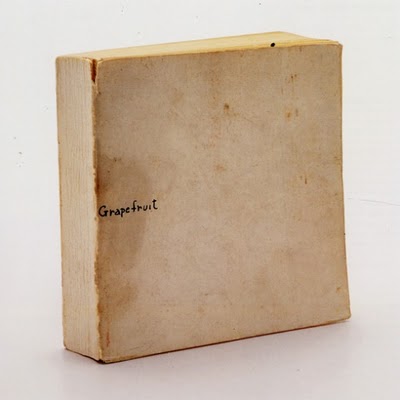

OG: Ono Grapefruit

Cross a first edition of Yoko Ono’s 1964 “event score”/instruction-based art book Grapefruit off my Ones I’ve Let Get Away list. Turns out it’s not just me:

There are no copies of the first (limited) edition of Grapefruit currently being offered in the marketplace. ABPC reports no copies at auction within the last thirty-five years. OCLC/KVK report only four copies in institutional holdings worldwide: At MOMA, U.C. – San Diego, Northwestern University, and the Library of Congress. What this tells us that all remaining copies are being closely held by private collectors. The book is exceedingly scarce in the marketplace.

Yeah, but. I’d also suspect a fair number of them didn’t survive long enough to be closely held. And she printed it in Tokyo, so I suspect there are a few in Japan that don’t show up in “the marketplace.”

Yoko Ono collects rare books [bookpatrol.net]

Grapefruit (book) [wikipedia]

The 1970 reissue of Grapefruit is pretty plentiful and cheap [amazon]

selected instruction pieces by Yoko Ono [a-i-u.net]

Walking Men, Or The Google Street View Trike Has A Posse

Some interesting developments since putting the Walking Man self-portrait collection out there. Thanks for the feedback and responses.

I think it’s becoming clearer that walking man is not, as I wrote, a guy who “came upon the Google Street View Trike preparing to map the Binnenhof” and who “decided to tag along.” Instead, he’s probably part of the Google Trike crew.

I’d always entertained the possibility, and when, after the initial burst of discovery and image extraction, I found some additional panos from around the lake that made it clear his relationship to the Trike was at least a factor in his appearances.

From the intro I wrote for the proof [which I’ll probably publish at some point, even as I plan to revise it for any future editions]:

His actions in the final two panoramas lend themselves to speculation: In his penultimate appearance, walking man becomes pointing man; he is seen gesturing across the plane, breaking the fourth wall, as it were, by addressing the Google Trike driver himself.

Perhaps this crossed a line about the presumption of passivity for Google’s photographic bystanders. Or maybe it violated some rule of non-engagement, a Street View Prime Directive. Is it possible that he’d been talking with the Trike rider, his personal [sic] camera operator, all along?

Yes, yes it is.

Continue reading “Walking Men, Or The Google Street View Trike Has A Posse”

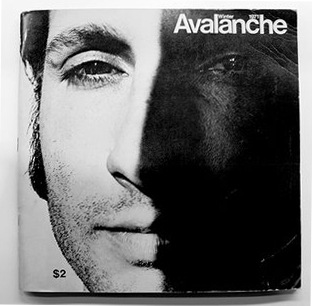

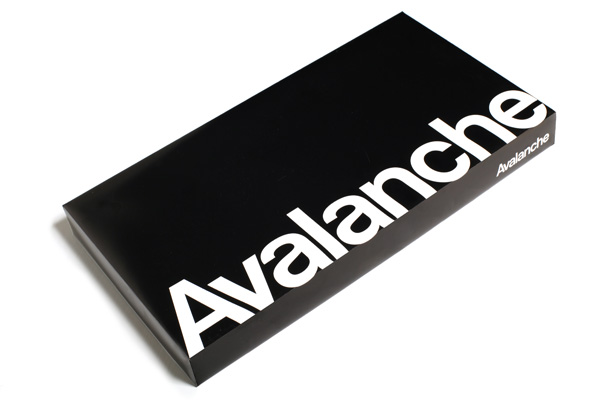

Finally, Primary Information’s Facsimile of Avalanche

You could argue that Primary Information’s facsimile editions of Avalanche, the awesome artist-run journal published in the mid-1970s by Liza Bear and Willoughby Sharp, are only the 3rd and 4th greatest editions of Avalanche, after Wade Guyton &co’s bootleg photocopied version from a few years ago [#2] and a complete set of the originals [#1, obviously].

You could argue that Primary Information’s facsimile editions of Avalanche, the awesome artist-run journal published in the mid-1970s by Liza Bear and Willoughby Sharp, are only the 3rd and 4th greatest editions of Avalanche, after Wade Guyton &co’s bootleg photocopied version from a few years ago [#2] and a complete set of the originals [#1, obviously].

But as a haggle-weary collector and scourer of vintage Avalanches over the years, I would argue that the greatest version of Avalanche is the one you can actually get.

So for the moment, that is the 100 limited edition, boxed sets of all 13 issues, which come with certificates signed by both Bear and Sharp [signed, obviously, before Sharp died in 2008]. Did I say 100? It’s only been a couple of days and the first 40 are already gone.

Which means that in a couple of weeks, at the latest, the greatest version will be either the trade edition, set to drop later this year, or the few signed versions which will immediately pop up on the bookflipping market. So plan accordingly.

Avalanche Limited Edition, now $450-750 plus shipping [specificobject.com]

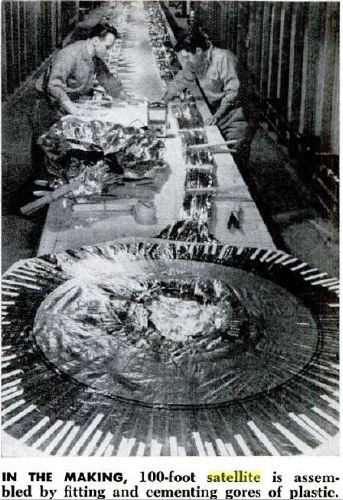

Echo I: The Making Of – Giant Clothespins

While I remember where it came from, here’s another image found in that Jan. 1961 Popular Science story starring William O’Sullivan Jr, who headed Project Echo and the whole satelloon paradigm at the fledgling NASA.

When you see a couple of guys at a 50′ table, assembling, folding, and gluing Echo I’s Mylar gores using not much more than a pile of footlong clothespins, you can understand why I still hold out hope of replicating one for exhibition as an art object. [On earth first, of course. Baby steps.]

‘If Echo were as fleet…’

Paul Brodeur in Talk of the Town, The New Yorker, September 3, 1960. The abstract pretty much captures the whole, short piece:

Comment on attending Shakespeare’s “The Taming of the Shrew” at Central Park’s outdoor Belvedere Lake Theatre.

We noticed that many of our fellow-theatre-goers were gazing upward at the stars & summer haze of the night sky…& we followed suit. With the opening lines, we realized that they were still lost in the galaxies overhead. We again directed our attention to the stage. The lord was saying, “Thou art a fool. If Echo were as fleet, I would esteem him worth a dozen such…” & suddenly, brought rigid by the unwitting bard, we turned our gaze aloft, where, shining majestically in sunlight beyond the pale of our night, Echo 1 floated in the west. For many minutes, as the satellite traveled toward its northeast solstice, we sat with tilted head, our spirit swiveling between past myth & future myth. Then, unraveling ourself from our involvement with Echo’s awesome journey, we returned to the bleachers at the Belvedere, and thence to Shakespeare’s Padua, filled with reborn wonder at the mastery of man.

And it turns out Calvin Tomkins himself did a long profile in 1963 of Dr John Pierce, who oversaw Project Echo at Bell Labs. Tomkins seems to focus on what I find most mind-blowing about the Echo satelloons: the whole thing was undertaken by a tiny, informal group, without a giant industrial-scale infrastructure. It was almost ad hoc and bricolage, something akin to making, not manufacturing.

Not sure when I’m going to have the time to read that…

image: a 40-second time lapse from Autumn 1960 of the Echo I satelloon in orbit, published in an extensive “making of/launching of” article in the January 1961 issue of Popular Science magazine.

Google Trike Plus One?

I have no idea who walking man is, and ultimately it doesn’t really matter to me; the portraits of him that got inserted repeatedly throughout Google Street View ultimately stand on their own.

But at the very end of his tagalong, there’s a shot where he points across the Google Trike’s path. He’s gesturing, perhaps even to the cyclist/Trike operator himself. Which underscores the possibility that walking man did not just happen across the Google Trike; he may be involved with it somehow, as a tech, or a chaperone, or even the driver’s friend.

When I saw artberri’s flickr photos [above] of the Google Trike and Buddy circling the plaza at Arata Isozaki’s riverfront tower complex in Bilbao, I began wondering if a two-man team might be standard Google Trike operating procedure.

If so, the top of that other guy’s head might be a prominent feature when these Street View images come online. We may have a whole series of Trike-based portraits on our hands.

Whoa, Autoprogettazione X Artek Mashup

HUGE news from on the Enzo Mari autoprogettazione X [Scandinavian Furniture Giant] mashup front:

The Finnish manufacturer Artek will announce ‘sedia 1- chair,’ “the first object from Mari’s thought-provoking project ‘autoprogettazione’ to go into production” with the company. “the first”!

Like the original “manufacturer,” Simon International, run by Dino Gavina, Artek will sell you a stack of pre-cut pine boards, some nails, and the instructions. Look at those wide boards, they’re built up, just like the tabletops on certain other autoprogettazione pieces I’ve seen from the region.

For the full press release/preview, and more shots of Mari building his own damn chair, thank you very much, go to designboom. [thanks andy]

Previously: the Enzo Mari X IKEA mashup saga

walking man – a self-portrait collaboration with Google Street View

In the Summer of 2009, an unidentified young man came upon the Google Street View Trike preparing to map the Binnenhof, the center of the Dutch government, in The Hague. He decided to tag along.

The man walked alongside the Google Trike, persistently inserting himself in the foreground of its nine computer-controlled cameras’ panoptic fields of vision.

Meanwhile, Street View’s automated panorama generation system read his presence as a data anomaly and consistently attempted to erase him from the photos.

The resulting images, extracted from nearly every Street View panorama of the Binnenhof complex, reveal the history and process of their own making. They are at once a minute detail in Google’s extraordinary, ongoing portrait of the entire world, and one man’s wresting of control of his own image and his audacious assertion of his own presence.

I discovered these images in February 2010.

At first, it was the distortions of time, space and perspective in these photos that caught my eye. As I began mapping out [sic] the scope of the project, however, I became fascinated by how this man seemed to travel almost precisely at the distance that simultaneously kept him in frame, but also all but guaranteed his algorithmic erasure.

Then I tried to understand the images as portraits, or self-portraits. As the exercise of the flaneur. The product of the flaneur’s gaze. An artifact of a moment in time, in space, evidence of the photographer’s decisions. As photos or cinema. Surveillance or subversion. Indexing, seriality. As virtual or real, documentary or manipulation, strategies or tactics. I looked at Muybridge and Marey. I went back to re-read Benjamin, Bergson, Barthes, de Certeau, Sontag, but these images seemed to thwart every attempt to put them into a critical or historical context as photographs.

And yet they’re so easy to look at and use; we all become Street View-proficient, if not fluent, within moments of our first encounter with it. And the walking man apparently made them on a whim, by doing nothing more than strolling along.

I decided to extract, compile, and print the entire set of photographs as a book. The title, walking man, is a reference to Alberto Giacometti, whose sculptural notions of distance and vision I was studying at the time. “Self-portrait” is an acknowledgment of their subject’s creative intent, and “collaborative” refers not only to Google’s operation of the camera, but also to their first pass at selecting images, and to the crucial aesthetic impact their manipulations have on the images they ended up publishing.

The images are actually screencaptures from Google Maps in Safari that include every appearance of walking man within each panorama. Though I composed each screenshot, I consider this a found work, or a work made of found images. Which is why I’ve been looking lately at work by folks like Sherrie Levine and Larry Sultan.

With three exceptions, each of the 55 Street View panoramas in the set is represented by one photograph which includes all portrait elements. The first panorama in the series includes both the walking man and his reflection in the window of the Binnenhof security office, but they are at too wide an angle to include in one screencapture. So the images were extracted separately After sending the book to the printer, I found that another panorama also included a nearly straight-down image of walking man’s legs, which would not fit within the browser window on my laptop monitor. The other exception, below, was just too beautiful to resist, there are so many awesome things going on in this photograph.

This proof copy was created using blurb.com. It’s 120 pages, and includes 57 portrait images and a reference Google Map, and a short introduction to the project. I thought the format might be too big, but it turns out it looks fantastic. The photos are a little dark, but that’s only because most of them were shot in the morning shade. My photos are dark because I shot them inside without a flash.

I am considering a limited print run, including editions reserved for the artist and the photographer, both of whom are currently unidentified.

There are several more shots from the proof on flickr.

Previous, related: How your Street View panoramas are made

The Meaning Of Maps, By Google’s Michael Jones

He’s pretty harsh on unnamed governments who complain about unblurred faces, and got more than a bit of engineer’s arrogance, which is why, I guess, he works for Google, but Michael Jones’s talk, “The Meaning of Maps,”at O’Reilly’s Where conference last week is pretty great.

Maps are not just place, they’re culture. Also, you get to see the Google Trike in action around the 13:00 mark.

CORRECTION: When’d The NGA Show Such Awesome Barkley Hendricks Paintings?

If there’s something I’m happy to be corrected on, it’s my assertion earlier this week that the National Gallery of Art has never exhibited its awesome, early, major Barkley Hendricks portraits.

It turns out they have, and here’s how we know:

I based my post on two things: the NGA’s online database of the paintings’ exhibition history, and discussions about the paintings and their documentation with folks in the archive and registrars’ offices.

Now a reader who has seen the location reports for each painting emailed to tell me they have, in fact, been shown publicly in the Gallery on various occasions. Turns out the exhibition history refers only to curated exhibitions, in or out of the NGA, in which a work is included. It does not include info on when apiece has been on public view. The location report, meanwhile, is basically a log of wherever a work has been or has been moved. And Hendricks’ paintings have been on view. Which is great.

On the real impetus for my post and my investigation, seeing if Hendricks’ paintings might turn up in the East Wing Galleries somewhere after completing their victory laps with the “Birth of Cool” retrospective, the reader was sanguine. Contemporary portraits are hard to work into the NGA’s hangs, but the appeal and buzz of the Hendrickses is hard to resist. So put that on your HOPE poster.

Thanks to my unidentified reader for the correction.