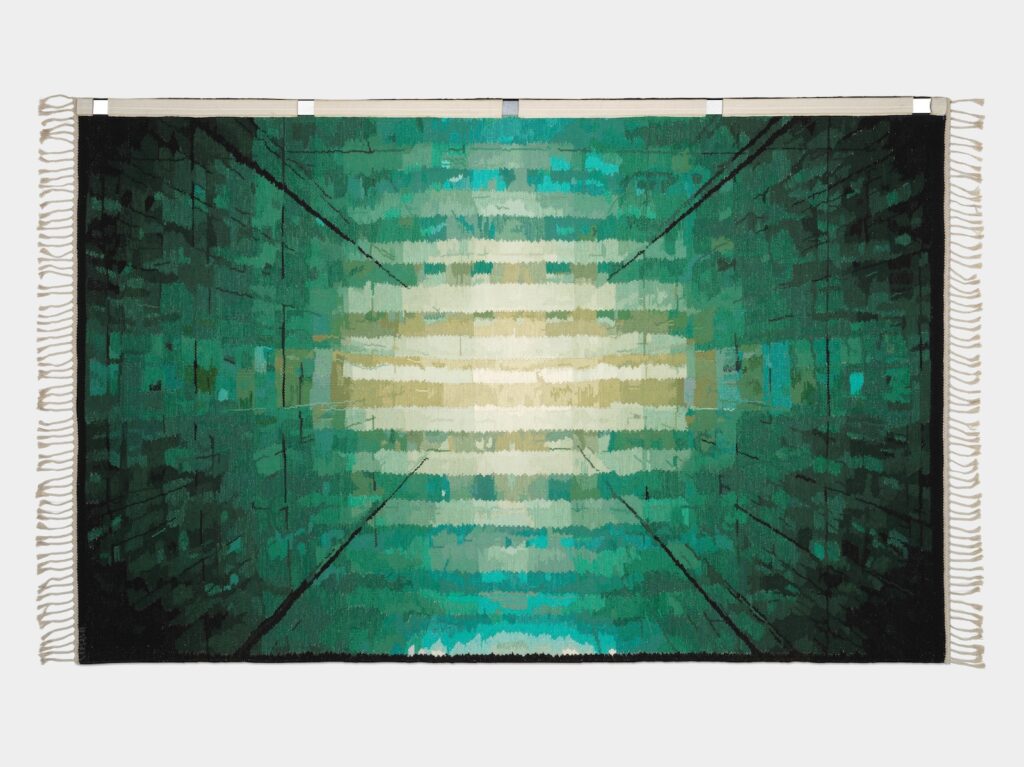

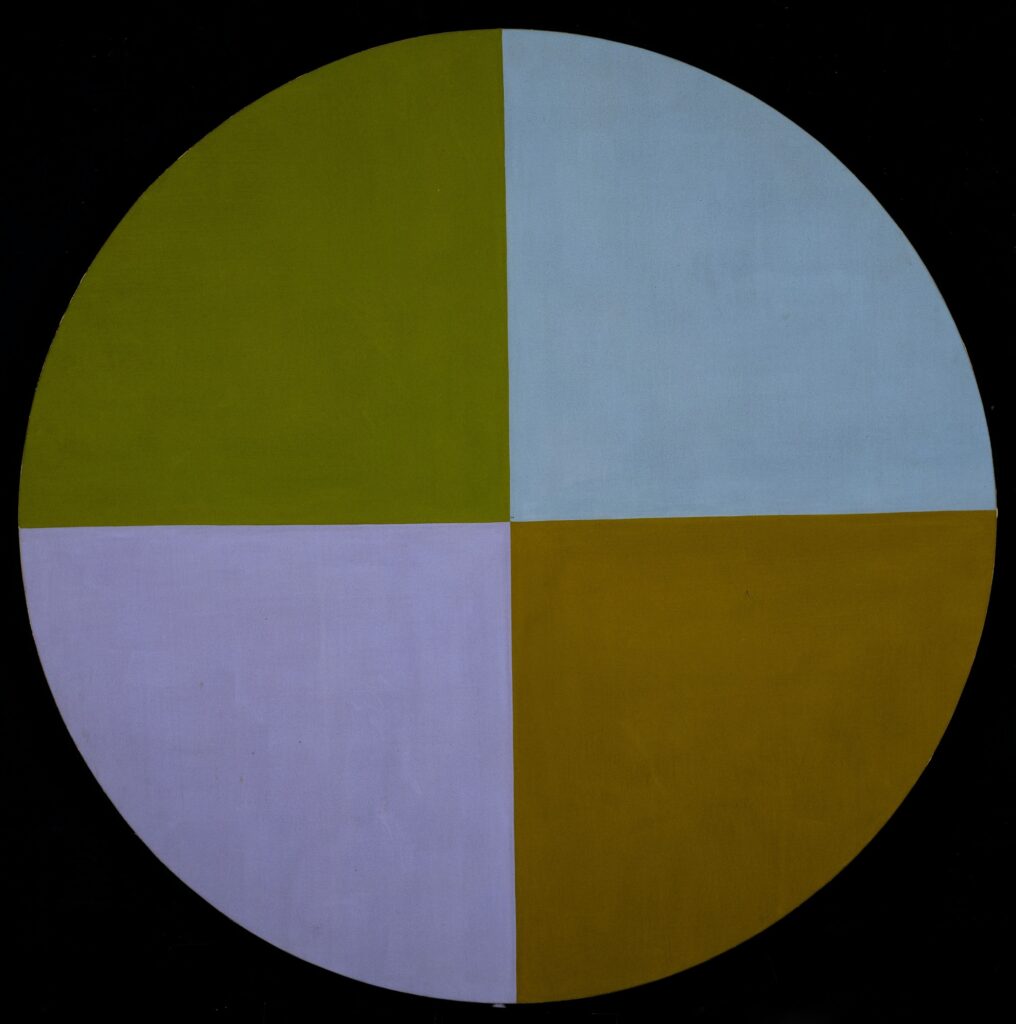

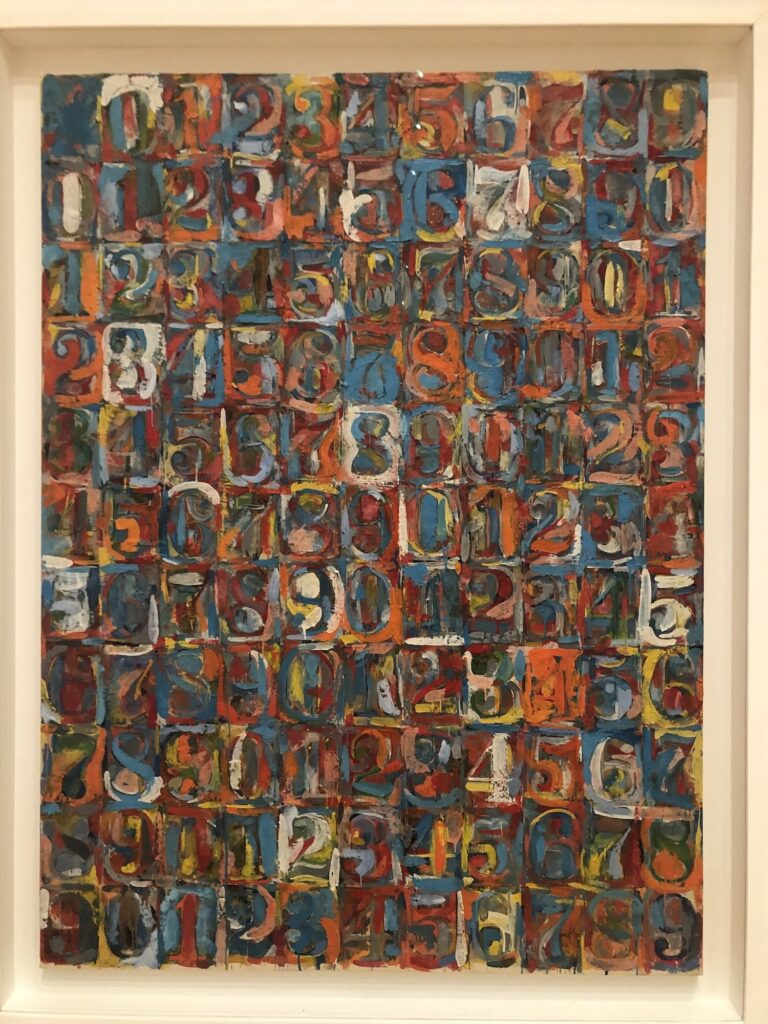

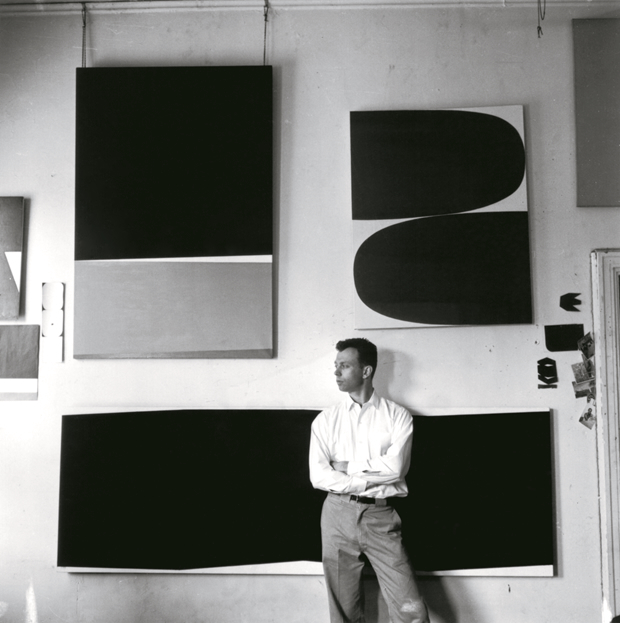

Last April during the centennial year of the artist’s birth, photographer Onni Saari posted a 1956 image to Instagram of Ellsworth Kelly in his studio on Broad Street in lower Manhattan. In addition to some tantalizing little works on paper and images stuck into the door frame, three paintings are visible behind him. Counter-clockwise from the bottom they are, Bar (EK87), Red Curves (EK81), and Marblehead (EK IDK?)

The first two, at least, were included in Kelly’s first show at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1956.

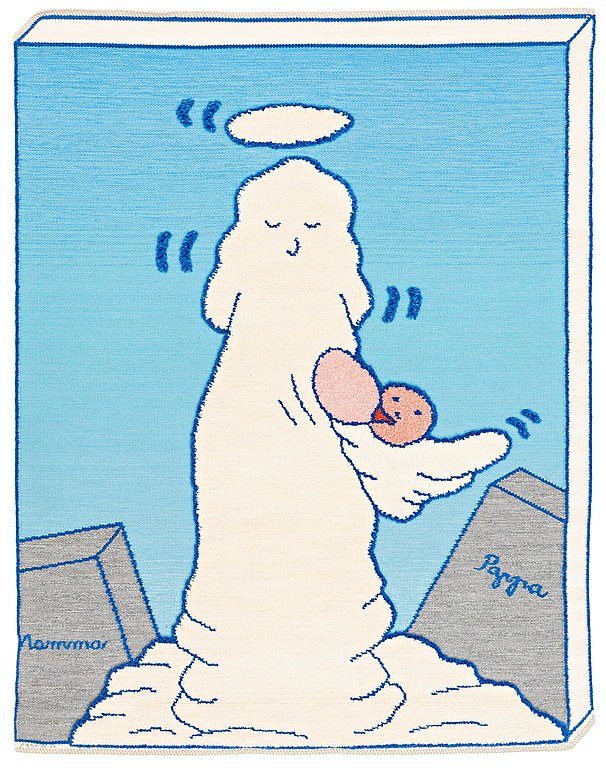

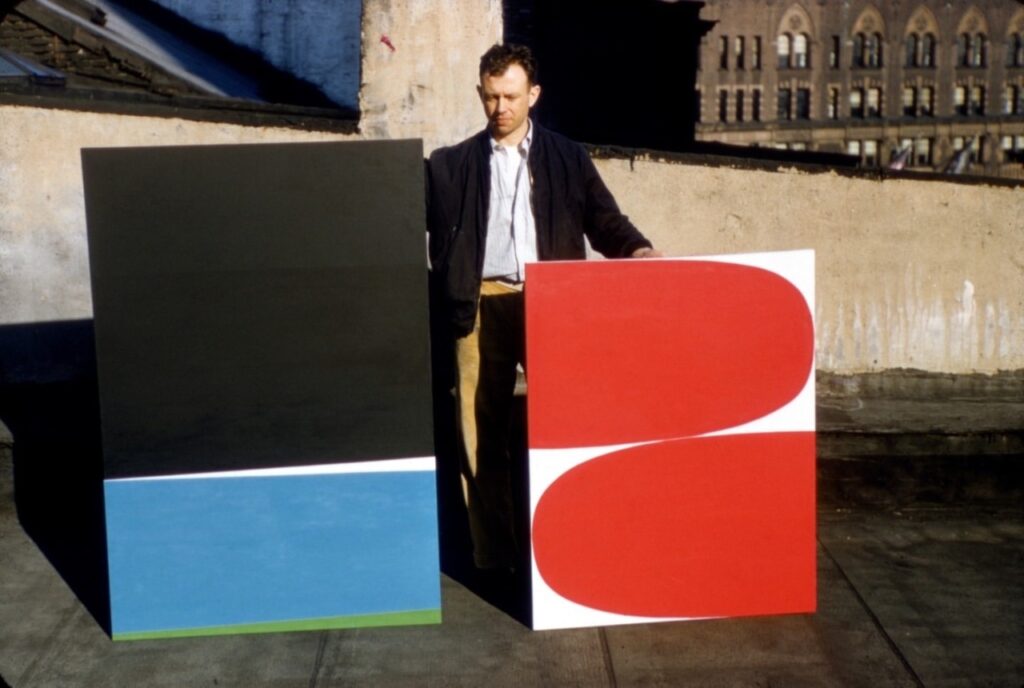

and Red Curves (right, 45×35 in.), photo: IG/ellsworthkellystudio via kundst and voorwerk

In November 2023, the Ellsworth Kelly Foundation posted this 1955 photo of the artist posing with Marblehead and Red Curves on his Broad St rooftop. The caption read, “Ellsworth considered Red Curves to be an epiphany of sorts, leading to many more curves, though the same cannot be said for Marblehead. The black, pulsing blue, and irregular bands made it a favorite with a Betty Parsons dealer [sic], but Ellsworth’s dislike of the composition was so strong that he destroyed it in 1995. ‘One I never cared for,’ a scrupulous Ellsworth wrote in his notes.”

The circumstances around Kelly’s decision to destroy Marblehead after 40 years intrigue me, but in writing this post, I have run out of time to get to the catalogue raisonné to find out what happened.

Previously, related: Destroyed Robert Gober Ellsworth Kelly Painting