Realtors and developers pay several thousand dollars/month to stage properties for sale. Staging companies move out the seller’s accumulated lifetime of crap and move in a whole array of tastefully bland furniture and accessories to make the place look or feel bigger or nicer. Remember that aristo hobo couple in Charleston in the Times a few years ago who basically live for free by moving themselves and their heirlooms into the plantations and spec homes they stage?

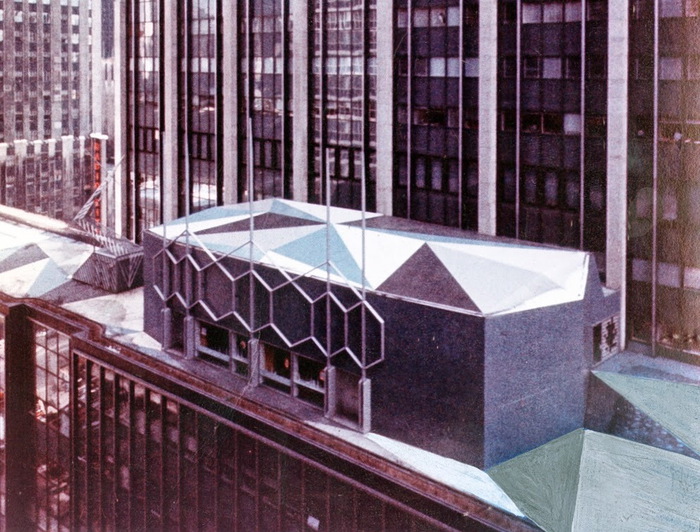

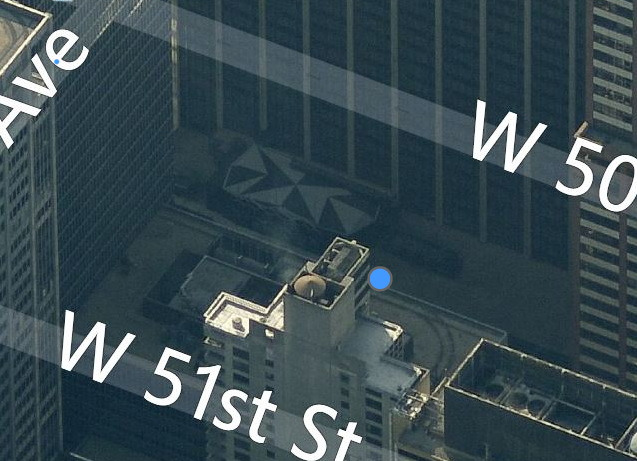

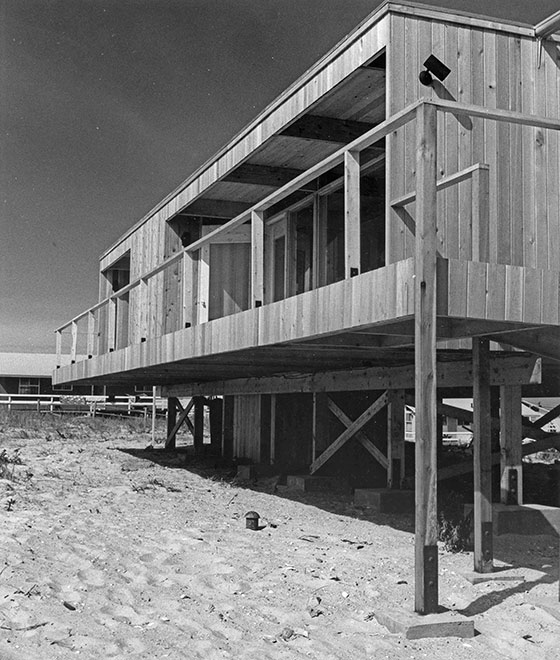

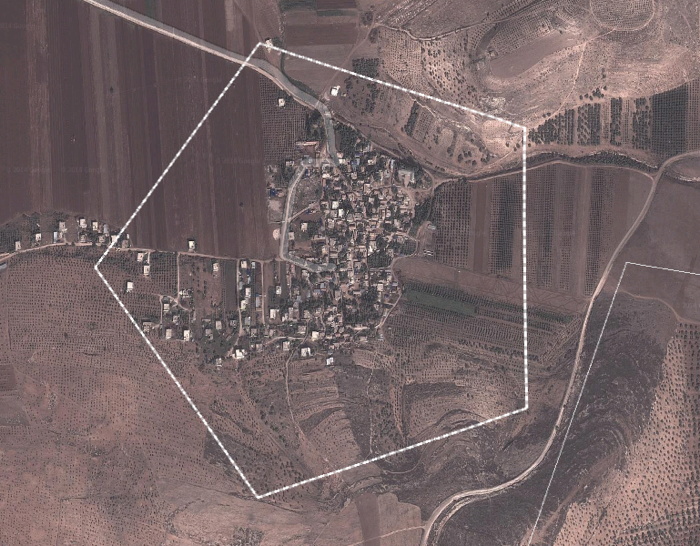

Wow, that was 2011, too. Which turns out to have been peak staging? Because I just found this bonkers story from Curbed in 2011 about InFormed Space, a staging startup that provides gatorboard ghosts of high end furniture, starting with a $14 million townhouse gutjob in Chelsea. From a NYDN story:

it’s easy to move the ultra-lightweight prop furniture in and out of spaces and it minimizes the pitfall of turning off potential buyers because of questionable décor choices.

“This helps you understand the space without confounding you with design,” [InFormed Space founder Douglas] Pinter said. “This shows you scale and volume in a way that doesn’t get in the way of your thinking.”

The “cool and minimalist” design of Pinter’s creations – many which are modeled after real pieces but aren’t legally copyright infringements because they are faux – may turn off diehard fans of, say, Queen Anne furniture. [emphasis added for awesomeness]

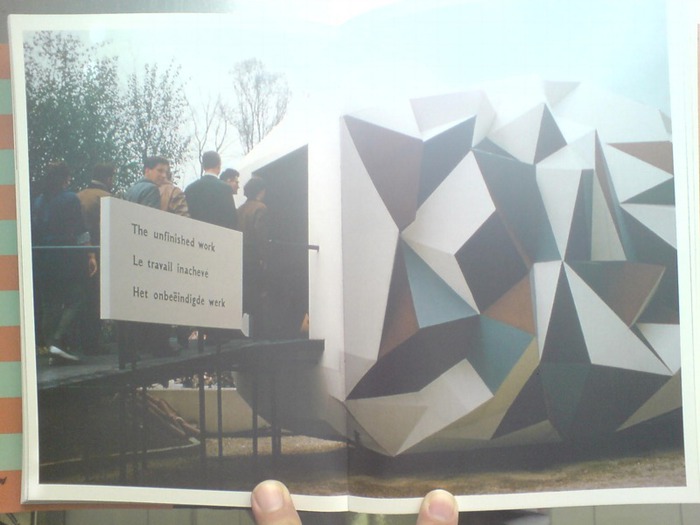

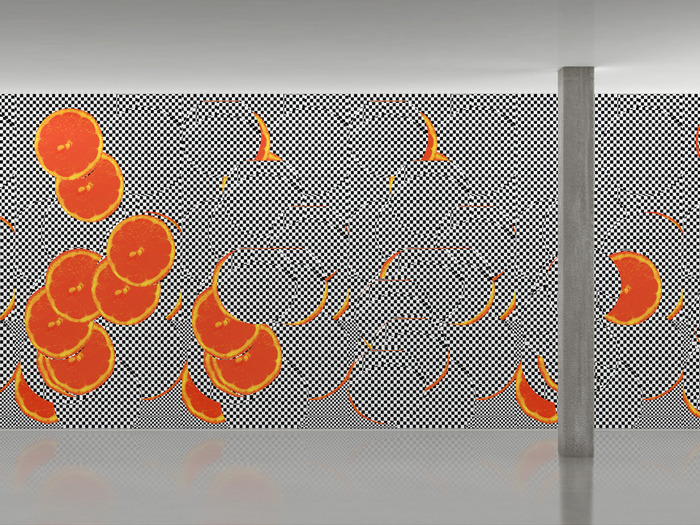

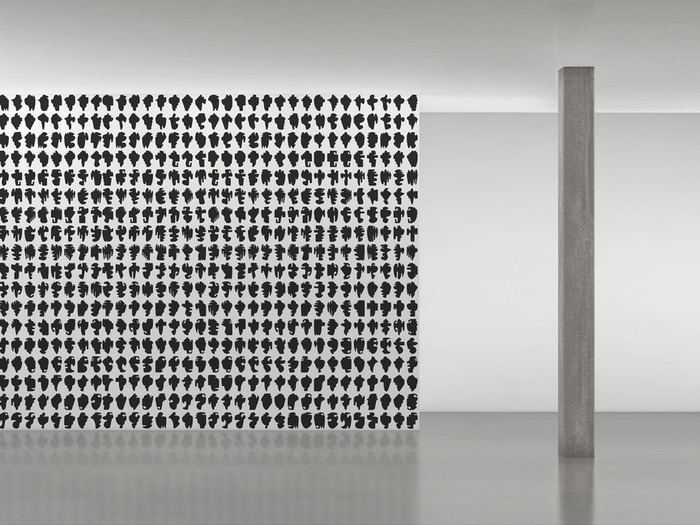

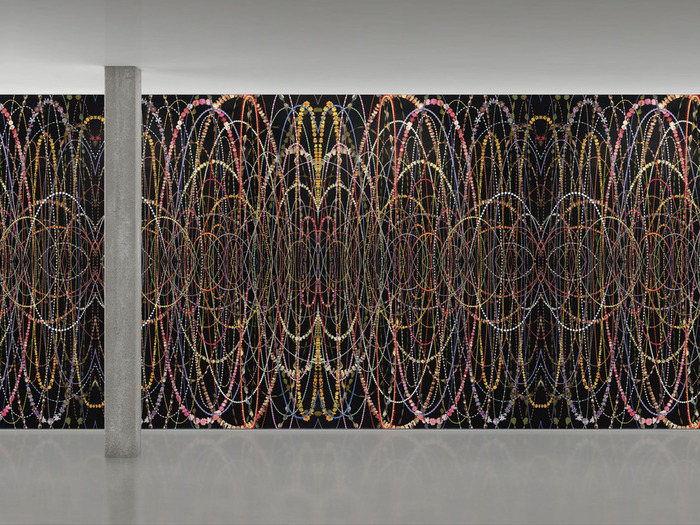

But wait, there’s more. There is art. Or as InFormed Space’s website [tagline: “A Stylish Quickie®”] calls them, “art panels.”

After Ad Reinhardt’s last paintings, after the monochrome, after the final declaration of the death of painting–for good this time, really, stake in the heart–the ghosts of paintings remain to haunt the walls of the living, until they are released by the exorcism known as the closing.

$14 million Chelsea townhouse gets decked out with fake furniture [nydn via curbed]