I finally pulled some pictures off my camera from last summer. That’s when I noticed this little bungalow–with a sweet, vertical addition–just off the mainstreet in Morehead City, NC.

There are a couple more shots on flickr.

Category: architecture

Dude. Olafur Eliasson Has A Blog

Well, he and his studio do. Spatial Vibration documents a series of collaboration/experiments concerning the relationship of sound and space. Several of the experiments are on view in a show of the same name, “Spatial Vibration, String-Based Instrument, Study II,” at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery through mid-June.

The Endless Study translates the sonic vibrations of a single-string instrument into a drawing by means of two pen-equipped pendulum arms, which record [sic] the sounds onto a rotating sheet of paper. It’s an update of a 19th century invention known as a harmonograph.

It remains to be seen what range of aural and visual effects emerge from the public’s access to the experiment. But the Studio crew, who have clearly been practicing, seem quite proficient at producing elegant, spiral drawings. But can you dance to them? Are beautiful drawings the happy accident of a particular type of performance, or is the musical composition–and the experience of listening to it–now incidental to the production of a desired drawing?

Meanwhile, another, even more ambitiously scaled experiment involves a 3-dimensional harmonograph, with a pendulum on each axis, which translates sound+time [i.e., a performance] into movement in 3D space. This path is then translated into a model. Olafur says it better:

By linking each pendulum to a digital interface I can ascribe to them the coordinates of x, y and z, and then digitally draw the spatial result of the three frequencies. They are easily tuned to a C major chord, for instance, one pendulum sounding the note C, one E, and one G. If they are given the correct frequency, the chord is harmonious and the vibrations form an orderly whole. This solidifies over time, thus drawing the contours of a three-dimensional object in space. In other words: sound vibrations can be turned into a tangible object. It is almost like building a model. One could develop this experiment into vast spatial arrangements by turning harmonious chords into spatial shapes. If we were to use a whole concert, like Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, we might build an entire city.

An entire city. But that returns me to my previous question: would you want to live in Beethoven’s Fifth? What if the highest quality of city life is produced by something musically awful, like Mariah Carey’s third comeback album? Or an annoying corporate jingle? Do you lay down a heavy bassline to produce your city’s street grid? What would be on Jane Jacobs’ iPod?

Spatial Vibration, includes video, photos, and exhibition info [spatialvibration.blogspot.com]

Spatial Vibration is on view at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery through Jun. 7 [tanyabonakdargallery]

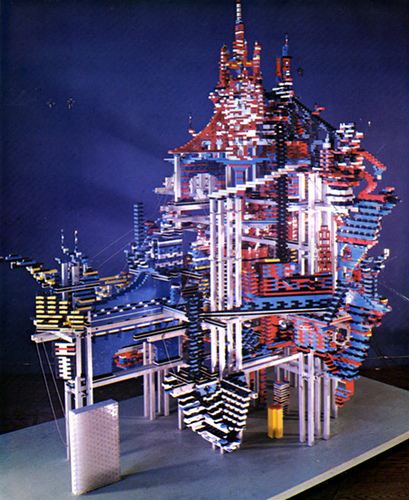

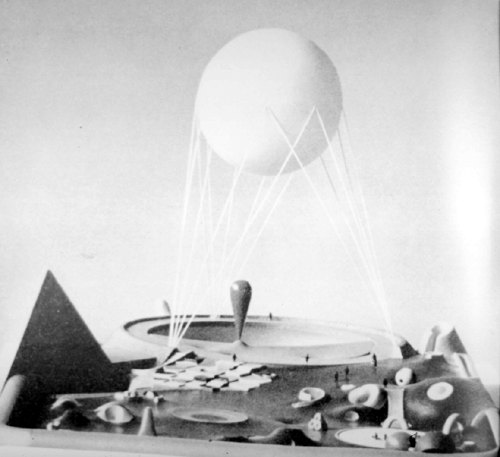

Lego City Of The Future, By Norman Mailer & Friends

If you had to name one American, for instance, who clubbed together with a couple of friends in 1965 and spent more than three weeks building a futuristic seven-foot vertical city out of Lego, you might not immediately think of Norman Mailer. Thirty-three years later, however, the city still stands in Mailer’s living room in Brooklyn Heights, and its creator remains enthusiastic about his project. “It was very much opposed to Le Corbusier. I kept thinking of Mont-Saint-Michel,” he explains. “Each Lego brick represents an apartment. There’d be something like twelve thousand apartments. The philosophers would live at the top. The call girls would live in the white bricks, and the corporate executives would live in the black.” The cloud-level towers, apparently, would be linked by looping wires. “Once it was cabled up, those who were adventurous could slide down. It would be great fun to start the day off. Put Starbucks out of business.”

Last fall after he died, the fate of Norman Mailer’s Lego “City of The Future,” which stood in his living room for more than 40 years, was not publicly disclosed.

I wondered what it looked like. Turns out, it probably looks a lot like the photograph of it by Simeon C. Marshall, which accompanied The New Yorker article on Lego from which the above quote was taken.

update: Basically, awesome.

This photo was used on the cover of Mailer’s 1966 essay collection, “Cannibals and Christians.” The city itself was Mailer’s own proposal for dealing with the looming crisis of sub/urban sprawl: “If we are to avoid a megalopolis five hundred miles long, a city without shape or exit, a nightmare of ranch houses, highways, suburbs and industrial sludge,” he wrote in a 1964 essay in Architectural Forum, “then there is only one solution: the cities must climb, they must not spread, they must build up, not by increments, but by leaps, up and up, up to the heavens.” Thus, the Lego city. [quote via arcchicago]

In Mary Dearborn’s Mailer: A Biography, the construction of the Lego City is portrayed as nothing less than a bold attempt by the author “to make a revolution in the consciousness of our time”–if only they could’ve gotten it out of the writer’s living room:

In many ways this was a typically Mailerian project. He announced it in advance in the pages of the New York Times Magazine and, to underline his seriousness, in Architectural Forum. The prose city he outlined would change the face not only of public architecture but of society itself. He had long blamed architecture for many of the woes of contemporary society, and now he applied himself to setting forth his plans in pronouncements and, beginning in the fall of 1965, the creation of an actual model city, immense in scale and meticulously planned.

…

He decided to build a model of a city that could be populated by 4 million people, and to build it in his own living room. He conceived it as a monument to his sweeping utopian vision.

At the quotidian level, Norman acted as the brains behind the project, soon discovering that he didn’t like the sound of the plastic Lego pieces snapping together; it struck him as vaguely obscene. He delegated the task to [fourth wife] Beverly’s stepbrother, Charlie Brown, who worked as a kind of handyman for him, and to Eldred Mowery, a friend from Provincetown now in the city. The two men drove Norman’s 1961 blue convertible Falcon out to the Lego plant in New Jersey and returned with cases of the colored blocks. Then Norman directed them, instructing them to create hanging bridges, buildings with trapdoors, and four-foot-high towers, all constructed on an aluminum-covered piece of plywood on a four-by-eight-foot sheet of plywood supported by five-foot legs.

Construction proceeded apace, and Norman never really did call a halt to it. But someone from the Museum of Modern Art came out to Brooklyn to take photographs of the model, hoping to display it at the museum. At that point, Mailer and his helpers found that the “city” could not be taken out of the apartment. though they consulted movers with cranes and took measurements of the glass in the front windows, they soon saw that it couldn’t be removed without being disassembled first. Here Norman drew the line. He told Mowery to build a fence around it and leave it where it was. There it still sits, occupying a third of the living room’s floor space. Beverly, who contributed a scale model of the United Nations to indicate the overall scale of the city, professes that she loved it, but concedes, “It was a bitch to dust.”

That must be the UN in the lower left corner there. As so often happens to builders of utopian Cities of The Future, Eldred Mowery was arrested several months later in an art insurance scam. Seems that in December 1966, he and an artist/carpenter friend broke into the Provincetown cottage of painter Hans Hoffman and made off with 41 paintings, which they tried to return to the insurance company for a reward. Only instead of insurance company executives, they handed the works over to undercover FBI agents.

Any photos or documentation in MoMA’s archives remains to be explored.

The Joy of Bricks by Anthony Lane, Apr 2, 1998 [newyorker.com]

Apparently some brickers sussed out the photo last December, too[brothers-brick.com]

Mailer: A Biography, by Mary V. Dearborn [google books]

Buy Cannibals and Christians on AbeBooks [abebooks]

Janet Jackson, Paula Abdul. Herbert Muschamp Is What The World Trade Center Is All About!

Choire’s interview with Elizabeth Berkley reminded me of some unfinished Showgirls business here on greg.org.

Back in 2002, right after Beyer Blinder Belle released the first, banal master plans for the rebuilding of the World Trade Center site, a parody critique circulated in the style of Herbert Muschamp, then the architecture critic for the NY Times. Finally, here it is:

A Critical Appraisal

Special to The New York Times

Striding down the row of design proposals for the World Trade Center site, balefully eyeing each inert mien and artificially enhanced plan, I was reminded of the scene in Showgirls where the choreographer grimly surveys his topless charges. Flicking a feather across their assembled nipples, he scolds, “Girls, if you are not erect, I’m not erect.”

Ladies and gentlemen, I’ve seen the master plan proposals from the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, and, to put it mildly, I’m not erect.

My heart sank as I watched John Beyer of the architectural firm Beyer Blinder Belle attempt to describe these hapless proposals. I was painfully reminded of another much more casual presentation one glorious autumn on Capri. The visionary Rem Koolhaas was holding forth on urban planning, shopping, life, and the smell of fresh basil. Wearing beautifully tailored trousers and a tight, cropped black top (need I add it was by Prada?) he gestured energetically as he spoke. With each gesture, his shirt rode up ever so slightly, revealing a tantalizing sliver of tan, taut tummy.

It is this kind of energetic gesture that those of us who care about contemporary architecture hunger for so desperately. Beyer Blinder Belle’s work is occasionally competent: certainly their by-the-numbers renovation of Grand Central Terminal pleases the hordes of moronic commuters who stream through it each day, but it will come as no surprise that this recidivist pile of marble is of little interest to the infinitely more important audience of attractive young European architectural students who make pilgrimages to our city each year and can barely choke back their tears of disappointment. John Beyer, whose exposed torso would be unpleasant for even the more adventuresome New Yorker to contemplate, must shoulder the blame for this catastrophic failure.

It is now time to list these names: Frank Gehry, Peter Eisenman, Zaha Hadid, Elizabeth Diller and Ric Scofidio, Tod Williams and Billie Tsien, Steven Holl, and, of course, Rem Koolhaas. There.

Is a little daring, a little excitement, a little sexiness too much to ask for on this sacred site? Lower Manhattan Development Corporation chairman John Whitehead and New York governor George Pataki would do well to rent a videotape of “All About Eve” and examine Bette Davis’s behavior before the big party scene. Her character Margo Channing reaches into a candy dish and hesitates again and again before finally popping a candy into her mouth. This tantalizing motif “impulse, surrender, gratification” is the central one of the twenty-first century. It alone must provide the ideological blueprint for all architectural work being done anywhere in the world, including lower Manhattan. If this fails to make sense to the theme-park obsessed corporate apologists for big business, so be it.

In the interest of full disclosure, my proposal for the site will be revealed at a time and place of my choosing. Fasten your seatbelts, New York.

Ignore, if you can, the glaring error that Muschamp would never have made: the choreographer used ice cubes, not a feather. The irony is that not only did Muschamp’s writing the last few years before his too-early death seem to cut loose, as if to meet his parodists in the sky, the fake WTC critique turned out too true by half: thanks to a sycophantic 1776 minstrel show from Daniel Libeskind and a chorus line of starchitects flashing their tits, the Port Authority’s original proposal is right on track.

[via mouthfulsfood]

Previously: Surely, Hordes of Showgirls-Googling Architects Can’t Be Wrong?

Breuer’s Whitney: NFSFN

So after the Whitney opens its downtown branch, it’ll sell its Marcel Breuer building on Madison?

That’s the way I read the blueprints being unfurled in the NY Times the last couple of months. Buried in a late December story led by the Smithsonian, Robin Pogrebin first floated the idea in this lighter-than-air paragraph. It’s not even a lob; it’s a feather, and so’s the denial:

Rumors have circulated that the Whitney might consider selling its 1966 building by Breuer, but [Whitney director Adam] Weinberg dismissed the idea. “That’s not going to happen, because we love it,” he said.

Then this morning, in Carol Vogel’s piece about Leonard Lauder’s $131 million pledge, the idea of a sale came up again, this time with a time frame:

Mr. Lauder said that the money required the museum not to sell its Marcel Breuer building on Madison Avenue at 75th Street for an extended period, although he declined to specify how long.

A idea of a Breuer sale is raised repeatedly and without attribution, then quickly, but just as squishily batted down:

Although Mr. Lauder’s donation is likely to quiet rumors that the Whitney might decamp from the Breuer building, the museum’s plans remain an open question. Since the Whitney set its sights on the meatpacking district, the city’s arts world has fretted that the institution might not be able to afford two locations.

Oh, has it? I’m clearly a MoMA fanboi, so maybe I’m just out of the loop–every loop in the city’s art world–but I have never heard a rumor or a plan or even a speculation about the Whitney selling its Madison Avenue building. Nor have I heard anyone fret that the museum, which has operated up to four locations in the city at one time, might be unable to operate two.

So unless these Times reporters are totally making this up, which I doubt, where are they hearing this? From Whitney insiders? Is a deal not to sell the building “for an extended period” substantively different from a plan to sell the building after “an extended period”?

Whitney Museum to Receive $131 Million Gift [nyt]

High five to Elmgreen & Dragset for their 2001 piece, Opening Soon / Powerless Structures, Fig. 242 [via tanyabonakdargallery]

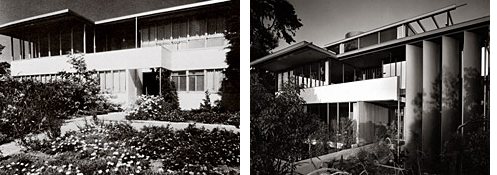

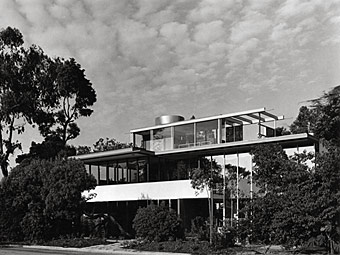

Save The Neutra! Sell The Neutra!

Holy smokes. On Archinect, Orhan has launched into a free-ranging, fantastical, and ill-informed lamentation over the impending doom that the callous, uncaring, neglectful architectural aficionado community is somehow foisting on the Neutra VDL Research House in Silverlake:

I wouldn’t elaborate on it at this finger pointing tone, but this is a city where you hear the words “inspired by Neutra” in various forms and places such as architects’ web sites, in countless design blogs, in real estate ads and of course in the circles of armchair design writers.

What abandonment.

Pages of coverage, with wall to wall color pictures, for so called Neutra specialists, when they re-build or renovate million billion dollar properties, which the architect and his pupil did years ago with clear aluminum sash and placed the glass in the right place. But, they don’t mention the VDL House, where it were all dreamed up and put to experiment.

…

After Mrs. Neutra’s death, the decay gradually became visible and impossible to hide.

Rudolf Schindler became the new hero of the Austrian invasion and people start to forget about Neutra for fashionable correctness. The same community who raised hell over a building next to MAK protected Schindler house, knew nothing of VDL house’ neighbors or didn’t care. Absurd and campy cliches like “Neutra was not as good as Schindler’ became part of groupie conversations in hipster parties.

It may very well be important for Neutra’s legacy; for the moment, let’s assume that it is. But the VDL Research House’s history is so deeply troubled, that the only conceivable way to save it is to sell it.

The current owners and stewards of the house, California State Polytechnic University, Pomona’s Dept. of Environmental Design [ENV], have proved utterly incapable of either using, maintaining, preserving, or promoting the Research House from the moment they were promised it in 1979 and from the moment they took possession of it in 1990.

According to the house’s own website, the “Urgent Campaign for Neutra VDL” has two purposes: to raise $30,000 immediately [by Oct. 2008, oops] for such basic operating expenses as insurance and utilities, and to raise $2 million, half for major repairs required after years of neglect [also resulting from original design drawbacks like putting a reflecting pool on the freaking roof]; and half for an endowment to provide ongoing operating expenses, and funds for programming and events for Pomona’s students and the broader public.

If this money can’t be raised, what will happen? According to the website, “the building complex is threatened with closure, possible sale to a private party, and quite possibly permanent loss of public and educational access.” Ooh, what abandonment.

The University that has neglected and underfunded the house for the 18 years since it received it, that apparently can’t fundraise successfully to support the house, and that lets major structural damage occur on their watch is now making an urgent plea for emergency funds. Meanwhile, they’re essentially holding the wounded building hostage, letting its conditions deteriorate until the inevitable finally happens, and the building is sold–and saved, finally–to some other entity who has a real commitment and the means to preserve it. And the only possible downside is “possible” loss of access.

The University generally and the Department of Environmental Design [ENV] specifically have demonstrated their total lack of commitment and interest in keeping the VDL Research House. In 2005, the University’s president launched a Priority & Response project to focus the school’s strategic and budgetary goals and needs. Here is a portion of a recommendation from the ENV Dean’s Office:

Over the past four years [i.e., since at least 2001. -ed.] ENV has attempted to raise funds for repairs to VDL, without much success. One impediment to fundraising is that the house is already named. Further, the VDL property serves a small portion of the ENV population of students and faculty. Since the house is 35 miles from campus, it is not a convenient location for seminars, weekly classes, or even receptions. While the College of Environmental Design recognizes this home as an icon of modern architecture, it is a much lower priority for fundraising than other projects, including a new building for the college, endowed professorships, scholarships, and a faculty development fund.

At the time of that recommendation, the estimated cost of needed repairs was $350-500,000, or half what is estimated today. The irony in several faculty statements in the P&R is not sweet:

[O]ur College is recognized nationally for its program in Historic Preservation, which has an emphasis on works of the twentieth century. The VDL house is a central feature of this program.

If that’s at all true, then the College should have its accreditation reviewed, because despite presiding over a modernist landmark built largely of manufacturer-donated materials, a pool of cheap-to-free labor and expertise, and [until very recently] a real estate/renovation/preservation boom, they have managed to push the Research House to the brink of disaster.

Proving themselves so unworthy, if the school and the Neutra fans in it honestly give a damn about the house, they’ll work to find it more capable owners, pronto.

1932: VDL I, by Richard Neutra

But is the house really so special it needs saving? It is certainly a Neutra design, but which design? And for that matter, which Neutra? It seems to be a question no one in the architecture community wants to bring up, lest it hurt the house’s chances for survival.

1963: VDL II, by Dion Neutra, I mean, “Richard and Dion Neutra”

But the basic timeline and the facts of the house are not in dispute: Richard Neutra built the front, studio/residence section of the house in 1932, and he added a courtyard house in back in 1940. The front house burned down in 1963, and a new house, with a new design, using new materials, was built on the foundation in 1965-6. The architect of record was Dion Neutra, Richard’s son, who had joined his father’s architecture practice.

According to Dion’s explanations of his working method with his aging father, and looking at at least some of the drawings for the Research House II, Neutra pere watched the fils design, and then gave him feedback. A glance at photos of the 1932 and 1965-6 incarnations of the house show dramatic differences. I’ll leave definitive historical judgments to the experts, but to my mind, the Neutra design needing saving right now is an Early Dion approximation of a Late Richard.

From self-serving online chats with students, to his delusional price comparison of his father’s office building to the paintings of “Klimpt & Pollack,” to the outsized bronze plaque/tombstone declaring his intention to have his ashes scattered in the VDL courtyard, Dion Neutra’s dogged insistence on inserting himself repeatedly and aggressively into his father’s legacy might be making it difficult for more clear-eyed, thoughtful preservation and scholarship to take root. It’s worth noting that Dion is not publicly involved with the VDL campaign in any way; his younger brother Raymond, a retired physician, is the family representative.

And while the Neutra family is to be commended for their dedication and efforts, you kind of wish–and by “you,” I mean “I”–that someone in the field would sit them down and talk to them frankly about the choices they need to make between actually preserving their father’s built legacy and perpetuating a well-meaning but disastrously flawed idea without a plan that puts that legacy at risk.

Frankly, the committees, boards and friends of Neutra VDL don’t look like they have the capacity to raise $2.03 million, and until they realize that themselves, the house will just deteriorate further. The only solution they seem able to provide is an introduction to an architecture collector who will take the property off their hands. They should hop to it.

Neutra VDL Research House v. Hard Times [archinect]

Neutra VDL Studio & Residences site [neutra-vdl.org]

Previously: Neutra For Sale: Calling Michael Govin [sic]

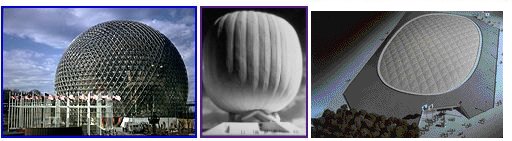

Ceci N’est Pas Un Satelloon

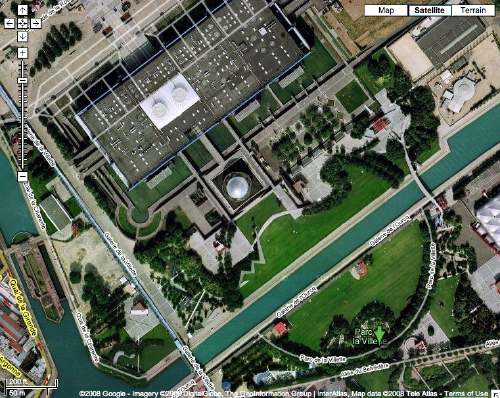

But darned if it isn’t pretty damn close. La Géode is a mirrored geodesic dome housing a hemispheric Omnimax theatre. It’s part of the Cité des Sciences et de l’Industrie, a science museum opened in 1986 in Parc la Villette, which I confess, I only knew as the site of Bernard Tschumi’s red follies. [There are a couple visible in the background here, and judging from this photo from another angle, they’re rightupthere next to the dome.]

At 34m across, Adrien Fainsilber’s stainless steel-clad Geode is the nearest approximation to the physical presence of a Project Echo satelloon that I’ve found. [Thanks to Stuart, actually, who tipped me to the recent post on extremely impressive shiny balls on deputy dog.]

Fainsilber’s site has more pictures, including the grainy-nice snap of the Geode nearing completion. and this amusing explanation:

Symbole de l’Univers, le reflet des nuages suggère la forme des continents et offre une vision immatérielle de l’environnement.

L’écran hémisphérique de 26m de diamètre de la salle de spectacle a engendré la forme sphérique de l’enveloppe.Symbol of the Universe, the reflection of clouds suggests the form of continents, and offers an immaterial vision of the environment.

The hemispheric screen of 26m diameter in the salle de spectacle [heh] engendered the spherical form of the envelope

I love it, a loopy mix of grandiose over-symbolism and bureaucrat-pleasing rationalization. As if the shiny steel awesomeness of the dome was somehow just the unavoidable by-product of the program the humble architect received. [Qu’est ce qu’on a pu faire? C’est logique.] Sure beats the “but it’s art!” pitch that was the last straw for the suits backing the Pepsi Pavilion.

Also, it’s an amusing stick in the eye of the deconstructionist, “form before function” conceit that Tschumi and collaborator [sic] Jacques Derrida put forward for the rest of the park.

I don’t know the story of the creation of Parc de la Villette, but Tschumi sounds like the Robert Irwin to Fainsilber’s self-important Richard Meier. Looking at the landscaping, la Geode has gone from being a Symbol of the Universe to just one stop of Tschumi’s David Rockwellian Cinematic Promenade. Or to the electron on a hydrogen atom. Which, as I zoom in with the all-seeing Google Eye to watch the picnickers in the Parc, i realize is so true. What if the whole universe were just an atom under the fingernail of a giant?

extremely impressiv shiny balls [deputydog.com]

Fainsilber > Realisations > CSI [fainsilber.com]

CSI and la Geode, and guests reading Le Monde, apparently, and letting their kids run wild [google maps]

Metaphysics of Parc de la Villette [gardenvisit.com]

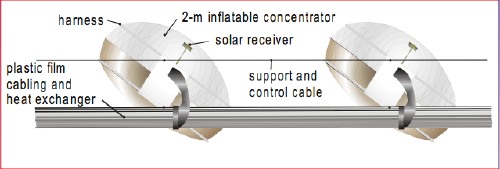

Solar Balloons Not Quite Satelloons

So I’m staring at these Solar Balloons by Coolearth Technology, caught like a deer in some headlights [actually, with this pair, maybe it’s “caught like a spring breaker in some headlights, but whatever], and I can’t figure them out.

Then I get it: one half of the balloon is clear; the parabolic–or parabola-like, anyway–reflector part is the inside surface of the other, opaque side of the balloon. 2-meter diameter. Not Satelloon-scale, but still, it’s good to know it’s out there.

Solar Balloons from Coolearth Technology [coolearthsolar via inhabitat]

No Kidding, It’s A Small World

After riding the It’s a Small World ride half a dozen times on my first trip to Disneyland, I sent off for information on how to become an Imagineer. I was seven.

Yet somehow it’s taken me until this week to realize that the treacly animatronic Mary Blair masterpiece was originally created by Walt Disney at the behest of the Pepsi-Cola Corporation, which wanted a popular pavilion for the 1964 New York World’s Fair. Disney was apparently commissioned to design four corporate pavilions that fair.

According to Billy Kluver’s long, rambling account/apologia published in the 1972 book, Pavilion, Pepsi was in talks with Disney to produce the 1970 pavilion in Osaka, too, but Disney’s budgets were orders of magnitude too high. Disney’s withdrawal in late 1968 left Pepsi with an empty pavilion to fill, and it created the opportunity for E.A.T. to get involved.

It’s a small world after all.

Joep van Lieshout: Those Who Can’t Do, Make Art

Now I’ve been a fan of Joep van Lieshout’s work for a long time, even if a lot of it’s too irreverent or too bombastically oversexualized to evangelize about regularly. [“You see, mom, he builds these room-sized uteruses with built-in bars…”]

But listening to his talk at Tate Modern last fall, it wasn’t his successes so much as his failures that stuck in my mind. The arc of the interview with curator Marcus Verhagen was the failure of AVL-Ville, Atelier Van Lieshout’s attempt to turn its Rotterdam waterfront studio complex into an independent, anarchic state, and how that flirtation with utopianism eventually led to the artist’s current dystopian fascination. The artist then explained his concept for a hyper-capitalist, sustainable, totalitarian slave city with a population of 200,000 that produces EUR7 billion in profits each year. So far so good [sic].

When it got to the Q&A, though, someone asked van Lieshout if his zero-impact utopia, with its organic urban farming, &c., was so great, why not keep developing it? He dismissed the idea, since it would involve actually running the thing, then it’d take expertise, and attention, and involvement with the bureaucracy, and anyway, who knows if it really works? [Obviously, I’m paraphrasing here.]

The gist of his reply, though, was reality’s too hard, so he’s leaving it as art.

Then when someone lobbed a generous softball of a question by describing his structures and installations as “cinematic,” van Lieshout punted again. Though he, too, conceives of his work as the sets upon which some unspecified drama unfolds, he never makes films, because he “doesn’t know how.”

I’d always thought of AVL-Ville as something of a conceit, but I had no idea how utterly dependent it was on the benign neglect of Dutch bureaucrats, and I certainly didn’t know how quickly and utterly it folded when faced with the most rudimentary challenge. And similarly, when even a clueless yahoo like me can figure out how to make a movie, expertise and technology just are not credible obstacles anymore.

Sure, art is not, by definition, the real world, but I’d always somehow considered it to be superior in its distinctiveness. And yet here was van Lieshout’s art being defined by its impractical, unproved inferiority in one case, and as the refuge for ignorance in another. We unconsciously give Art a presumption of cultural significance that, what do you know, it may not automatically deserve.

Too often, it gets considered only on its own terms, in a bubble, a world [sic] apart from the real world. It’s why the mediocrity of an artist like Mariko Mori gets taken seriously when it’s dwarfed technically and philosophically by CG and narratives of the best films and video games. Or why a piddly little spiral jetty is raised to masterpiece status while the US Army’s vast earthworks at the nearby Dugway Proving Grounds are ignored and detested. There’ll be a reckoning some day, a reality check, and a lot of art that was considered intrinsically valuable or important will end up as worthless oddities, like 19th century jewelry made from that most rare of metals at the time, aluminum.

Talking Art | Joep van Lieshout [tate.org.uk via imomus]

Meanwhile, In The American Pavilion…

Here’s a description of the American Pavilion at the Osaka ’70 Expo from an online exhibit at Columbia called, “Housing The Spectacle: The Emergence of America’s Domed Stadiums”:

Trying to best R. Buckminister Fuller’s Geodesic Dome built for the U.S. Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, the architects of the Expo 70 Pavilion first envisioned it as a huge floating sphere, inspired by NASA’s Apollo 11 mission that put the first man on the moon. This spherical scheme was the winning entry (submitted by Davis – Brody Architects and deHarak, Chermayeff & Geismar, Designers) in a competition sponsored by its future owner, the United States Information Agency (USIA). The competition scheme would have included exhibition space inside the sphere, and used its inner surface as a giant projection screen for continuously played film clips. The Pavilion ultimately erected at Osaka marked the birth of a new structural building type — the longspan, cable stiffened pneumatic dome — which would for a time become the predominant roof system over America’s emerging sports palaces. Remarkably, the U.S. Pavilion’s pneumatically supported 465 foot by 265 foot clear span dome was developed largely in response to Congress’ 50% reduction in the project’s budget. The completed Pavilion cost $450,000, which was about half the cost of the Montreal dome.

Those budget cuts meant The Great Balloon was replaced by a flat, quilted dome derided as “the world’s largest bunion pad.”

“Space balloons” were a prominent element in another of designs invited by the US Information Agency. According to an exasperated-sounding 1968 Architectural Forum review of ten of the eleven invitees, Isamu Noguchi proposed an underground exhibition space topped by a “vividly colored” and contoured playground landscape, comfortably shaded by a giant balloon. A space balloon.

Davis Brody’s winning plan for the Great Balloon originally included a spiral exhibition-filled ramp leading up to a panoramic platform where films would be projected on the entire upper half of the dome.

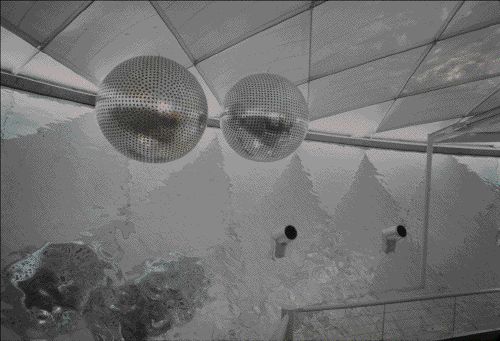

When that didn’t work out, the quest for giant, space exploration-evoking spheres, though, seems to have been moved inside. I can’t make much sense of the exhibition design or its purpose from photographs [the clearest picture I’ve seen so far is a tourist’s snapshot], but there were certainly some Project Echo-esque Mylar spheres floating in there.

Also, the entire surface of the earth berm walls were covered in silver Mylar.

Especially with the dot-covered spheres, you see how short a trip it is from the Triumph of the Cold War and the Space Race to the Age of Disco.

There are more and larger images at the Columbia site. [columbia.edu]

The US at Osaka, Arch Forum, Oct. 1968 [hosted at columbia.edu]

Previously considered unrelated. Now? Helmut Lang’s self-portrait, a scavenged, battered disco ball

Q: Was The Pepsi Pavilion Art?

Of course, I’d only need to recreate The Pepsi Pavilion from Osaka 70 if it didn’t exist anymore. Does it? No. As relations between Pepsi and Billy Kluver, the engineer founder of E.A.T., deteriorated over issues of budget and esoteric programming [Pepsi had originally envisioned their dome-shaped pavilion as a site of a string of rock concerts to entertain The Pepsi Generation coming to the Expo], Kluver argued that the entire Pavilion was a work of art and thus, a success, and thus, worthy of continued expenditure and preservation. Pepsi, literally, wasn’t buying:

As an artistic experiment, though, it can be considered a success, and according to Klüver deserved to be treated as an art work.

In the case of the Pavilion, he therefore suggested to Pepsi-Cola to officially recognize the total work as an art work, in order to give it a legal structure. In a letter to Donald Kendall, President of Pepsi-Cola, Inc., he wrote “Our legal relationship to Pepsi Cola has developed so that the artists are put in the category of commercial artists designing a commercial product. One consequence of this is that we must obtain rights from all artists and engineers and others involved, particularly with regard to use of the Pavilion after Expo ’70. Of course, there is no question of Pepsi’s ownership and right to use and exhibit the Pavilion. Our dilemma is whether the artists have created a work of art or a work of commercial art to which there are rights which must be guaranteed… A decision to recognize the Pepsi Pavilion as a work of art and to treat it as such will set a much needed precedent in this area.” Pepsi-Cola never took this step and eventually the Pavilion was left in a state of gradual desolation and decay. This was certainly due to the fact that the relationship between E.A.T. and Pepsi-Cola had considerably cooled down, to the point that the company, the sole sponsor of the project, withdrew its support when E.A.T. presented a maintenance contract for $405,000, instead of the proposed sum of $185,000.

Too bad the strategy didn’t work; art seemed to be the only ticket to surviving the end of Expo 70. Today, almost all that’s left of Expo ’70 are Taro Okamoto’s massive sculpture, Tower of The Sun, and Kiyoshi Kawasaki’s International Art Pavilion, which until four years ago, housed the National Museum of Art, Osaka. Whoops, never mind: “The old museum was demolished and turned into a car park.”

From Ch. 2, “The Nine Evenings,” of M.J.M Bijvoets’ Art As Inquiry [stichting-mai.de]

No museums, but m-louis’s Expo70 photos do have sweet pavilions and the Tower of The Sun [flickr]

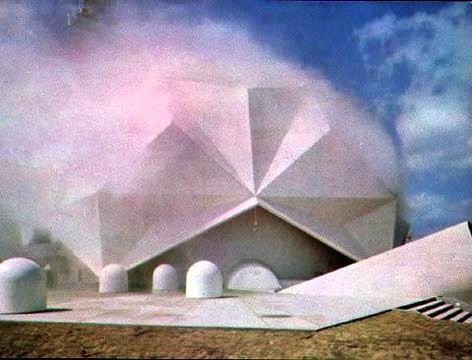

E.A.T. It Up: The Pepsi Pavilion

Let’s get one thing out of the way first: I’m a Diet Coke guy. The very fact that The Pepsi Generation existed in 1970 should blow a hole in their brand’s supposed youthy credibility big enough to drive a 90-foot mirrored dome though. Oh, and what do we have here?

Holy freakin’ crap, why has no one told me The Pepsi Pavilion at the 1970 World Expo in Osaka was an origami rendition of a geodesic dome; obscured in a giant mist cloud produced by an all-encompassing capillary net; surrounded by Robert Breer’s motorized, minimalist pod sculptures; entered through an audio-responsive, 4-color laser show–yes, using actual, frickin’ lasers– and culminating in a 90-foot mirrored mylar dome, which hosted concerts, happenings, and some 2 million slightly disoriented Japanese visitors?

And that large chunks of it were conceived, developed, and programmed by E.A.T., Experiments in Art and Technology, the pioneering art/engineering collaborate founded by [among others] Robert Rauschenberg and Bell Labs’ Billy Kluver? And that the four artists working with Kluver–Breer, Frosty Myers, Robert Whitman, and David Tudor–had planned months of even freakier happenings for the Pavilion, but the Pepsi gave them the boot for being too freaky–and for going significantly over budget? Still.

The least you could’ve done is tell me that Raven Industries made a full-size replica of the Pavilion out of Mylar and test-inflated it in a disused blimp hangar in Santa Ana, CA? Apparently, all it took was a 1/1,000th of an atmosphere difference in air pressure to keep the mirror inflated within the outer structure.

Because, of course, you know that Kluver was the guy at Bell Labs who helped Warhol with his seminal “Silver Flotations” exhibit in 1966 [seen here in Willard Maas’s film poem on Ubu]. And Bell Labs was involved in Project Echo, which launched and tracked two gigantic mylar spheres, satelloons, a couple of years earlier. Which makes the Pavilion’s similarities to the satellite below purely non-coincidental.

Which means that after recreating these two, earliest NASA missions as art projects, I’ll have to recreate the Pepsi Pavilion, too.

I’ve ordered by copy of Kluver et al’s dense-sounding 1972 catalogue, Pavilion and expect to be revisiting this topic in some depth within 5-7 business days. Meanwhile, if there are any other giant, mylar spheres of tremendous-yet-overlooked artistic and historical importance lurking out there, now’s your chance to come clean.

E.A.T. – Experiments in Art and Technology «Pepsi Pavilion for the Expo ’70» [mediaartnet.org]

Previously: Must. Find. The Satelloons Of Project Echo

D’oh, or else I must make the satelloons of Project Echo, which would mean I’m an artist, freak, or both

On Tomason, Or The Flipside Of Dame Architecture

Atelier Bow Wow is my favorite Japanese architecture firm. Rather than by building or proposing some kind of Roarkian vision, they first made a name for themselves [besides the catchy name they made for themselves, I mean] by observing and reporting architecture as it was inadvertently happening in Tokyo.

They put out exhaustively researched but in no way comprehensive books: Pet Architecture documented the ways structure took shape in the impossibly narrow spaces of a city where no scrap of land goes unused. Made in Toyko was about ridiculous hybrids: a department store with a driving school on the roof; a cement factory integrated with the workers’ dorms. They called these ridiculous, pragmatic spatial phenomena dame [dah-may] architecture, using the Japanese term for “no good.”

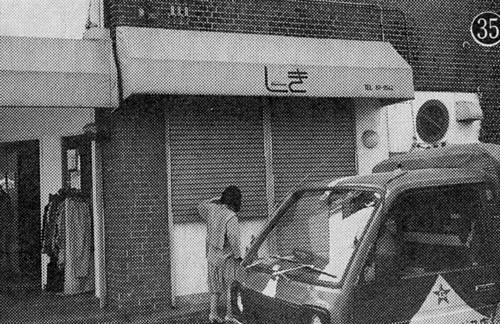

Such ad hoc, aggressively undesigned accidents stick in my mind as I read about Tomason [also spelled Thomason and Thomasson in English]. If dame architecture is the awkward result of relentless functionality, Tomason are the useless, abandoned leftovers. Stairs to nowhere are a favorite. Bricked up windows are a close second. Tomason are the flashings and detritus of the incessant churn of building, destruction, and redevelopment that characterizes the Japanese city. No clean slates here, no way.

The term comes from the art & architecture collective formed in 1986 known as Rojo Kansatsu [Roadside Observation], which counted the author/artist Akasegawa Genpei as a founding member. Rojo’s inspiration was Gary Thomasson, who was given the biggest contract ever in Japanese baseball in 1981-2, only it turned out he couldn’t hit; then he blew out his knee. He was a giant, useless lump on the bench.

Rojo exhibited at the Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2006 [i.e., the architecture biennale, not the real one. heh], but I found out about Tomason from an essay on neojaponisme. Like everything there, it’s too long by design. The image below from neojaponisme, of a store shutter without a storefront, is from one of Akasegawa’s original books. It reminds me of some of the Powerless Structures sculptures by Elmgreen & Dragset.

There’s also a rather nice photopool on flickr. here’s the japanese tomason tag and here’s the thomason group.

Roadside Observation [neojaponisme.com]

And In Further Platinum Rhomboid Tessellation News…

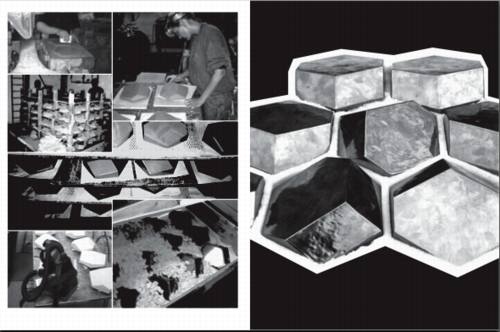

At the risk of devolving into an Olafur fanboi site, I’ll mention that I was flipping through Take Your Time, the photodocumentary magazine published by the studio in November. Turns out there are multiple shots of the making of for the quasi-brick tile installation in Tadao Ando’s Yu-un house project for Japanese collector Takeo Obayashi.

Here are some much-reduced screenshots from the PDF version. It’s one of the remarkable things of Take Your Time, glimpsing the extent and diversity of the indsutrial/production processes which generate Eliasson’s art objects. Outsourcing fabrication is so commonplace these days in the art world, but Olafur’s approach is the diametric opposite. He develops these highly specialized production capabilities for what’s essentially a very-low volume factory. The R&D’ll kill you, but the gross margins on those tiles has to be phenomenal.

Above: In-house production and packing of the tiles.

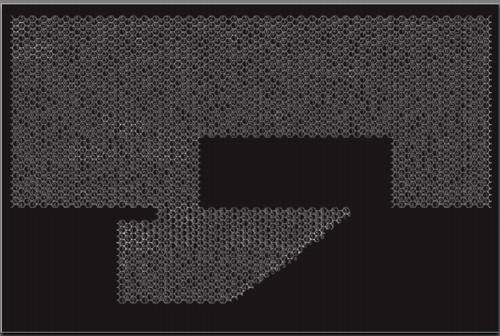

The installation template described by one of Eliasson Studio’s architects, which incorporates randomly generated position instructions applied to the AutoCAD diagram:

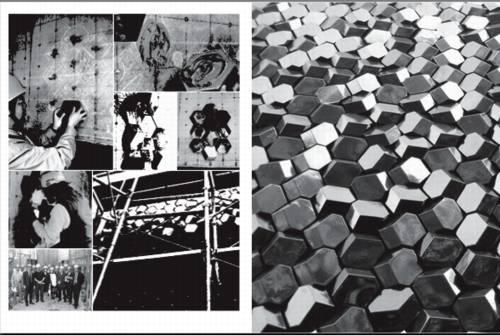

Construction crews installing the tiles in Tokyo [l] and the finished wall [r]

Previously: And what do you do, Mr. Ando?

Olafur: the Magazine??