In a 1970 paper, two Harvard/Smithsonian scientists proposed A Passive Stable Satellite for Accurate Laser Ranging. Dubbed project Cannonball, the 38-cm spherical satellite would be covered with triangular reflectors and would weigh–did someone drop a decimal?–a prodigious 8000 pounds. Cannonball would be a stable laser target which would allow surface mapping of the earth with 10cm accuracy by reflecting laser light between earth base stations. It was designed to be launched using an extra Saturn rocket left over from the Apollo program, but it didn’t happen.

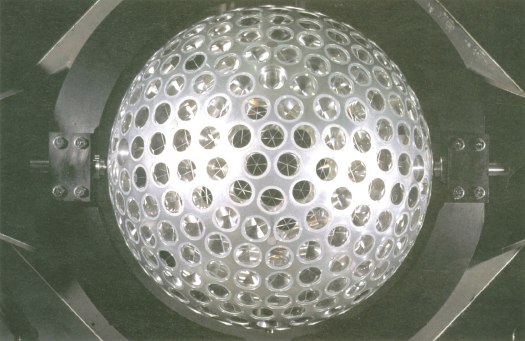

The passive laser reflector disco ball-lookin’ satellite trend didn’t really kick in until 1976, when NASA launched LAGEOS I [LAser GEO-something Satellite, above], which was built by ASI, the Italian Space Agency, from a NASA design. The 60cm-diameter aluminum-coated brass sphere is set with 426 cube-cornered retro-reflectors–4 are germanium, the rest are glass.

ASI built another, identical satellite, LAGEOS II [below], which was launched in 1992.

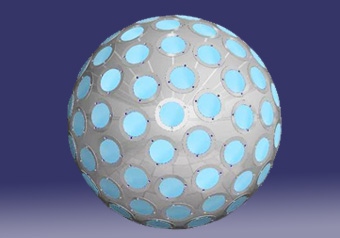

A third passive retro-reflector satellite, called LARES, was designed as an all-Italy project, and is set to launch in 2009 on an ESA rocket. LARES is smaller [36cm], made of solid tungsten, and contains 92 retroreflectors.

In 1989, Russia launched two Etalon satellites [below], which are each 1.3m in diameter and contain 2,145 retro-reflectors.

NASA launched Larets, a tiny 21cm sphere with 60 prismatic reflectors into low-earth orbit in 2003. It is very similar in design to the German GFZ-1 [below], which was launched in 1995 and burned up in 1999. They also look llike Buckminster Fuller Fly’s-Eye Domes.

The most disco ball-looking of all, though is Project Starshine, a series of three student project satellites [??] which launched between 1999 and 2003. Built from spare hardware, each Starshine sphere was covered with almost 900-1500 mirrors polished by students around the world. The satellites reflected sunlight, enabling a network of schools to track their movement. They all burned up as they re-entered the atmosphere, and Starshines 4 & 5 have been waiting for a ride into space since 2004.

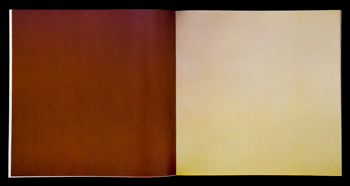

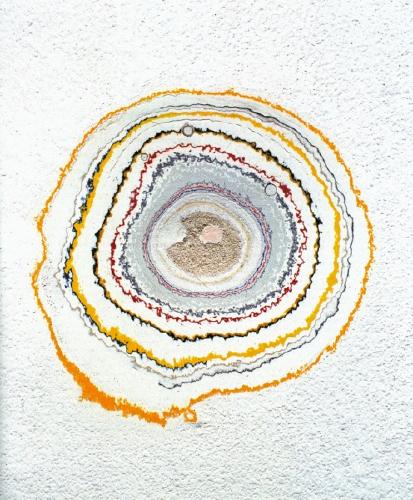

LAGEOS I also contains a plaque [below] designed by Carl Sagan and drawn by Jon Lomberg. It consists of three maps showing the position of the continents in the distant past, the present, and 10 million years from now, when the satellite is expected to re-enter earth’s atmosphere. The idea being, I assume, to let whoever retrieves the beautiful, shiny artifact from space some time before that happens know that we totally knew they were going to do that.