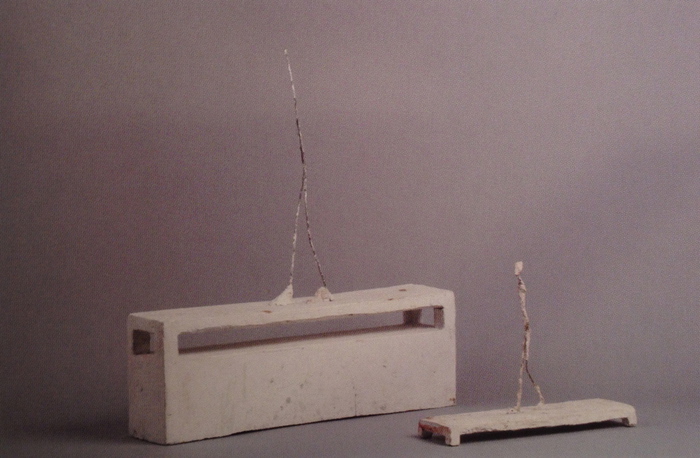

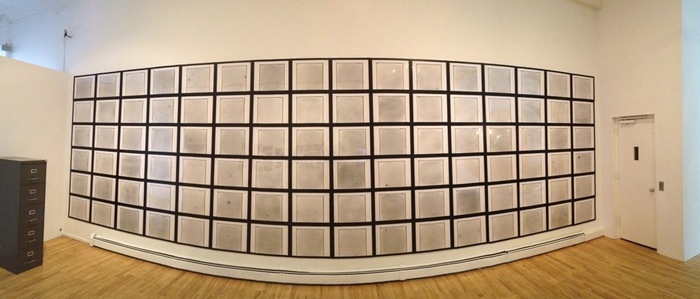

Isa Genzken’s World Receiver in “Night” at The Glass House, image: Amanda Kirkpatrick

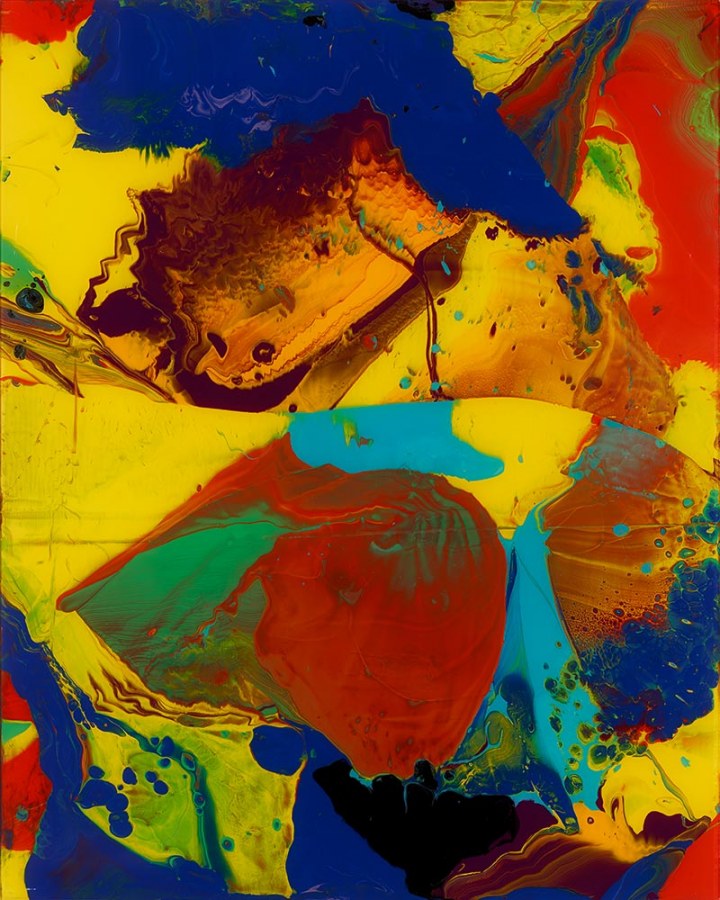

I was talking to a friend who recently got his first work by Isa Genzken, a World Receiver, (which really is the best first Genzken to get, and the third, and the seventh-they look great alone or in groups!) and it reminded me of one of the best installations ever of the radio-shaped cast concrete sculptures. Last fall a World Receiver was the last work in a fascinating 3-year exhibition called “Night”, which took place on the coffee table in Philip Johnson’s Glass House.

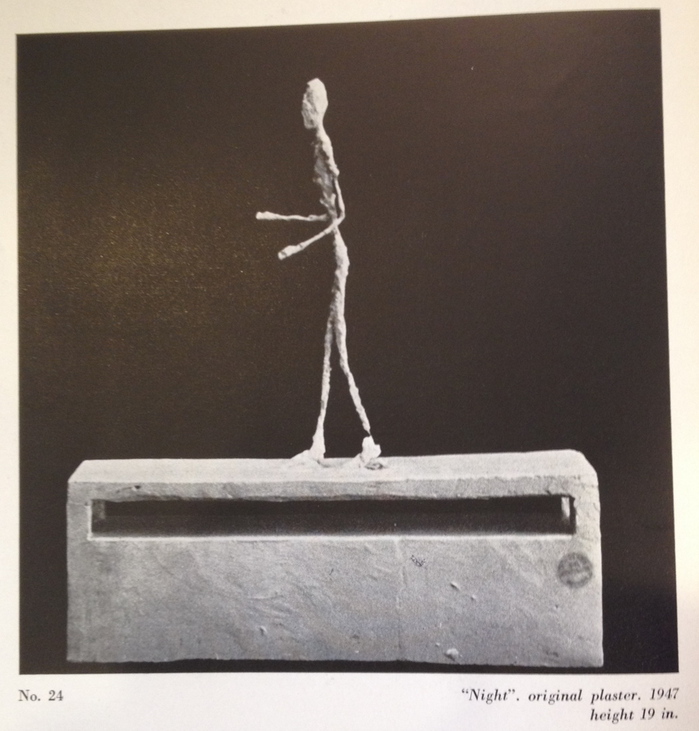

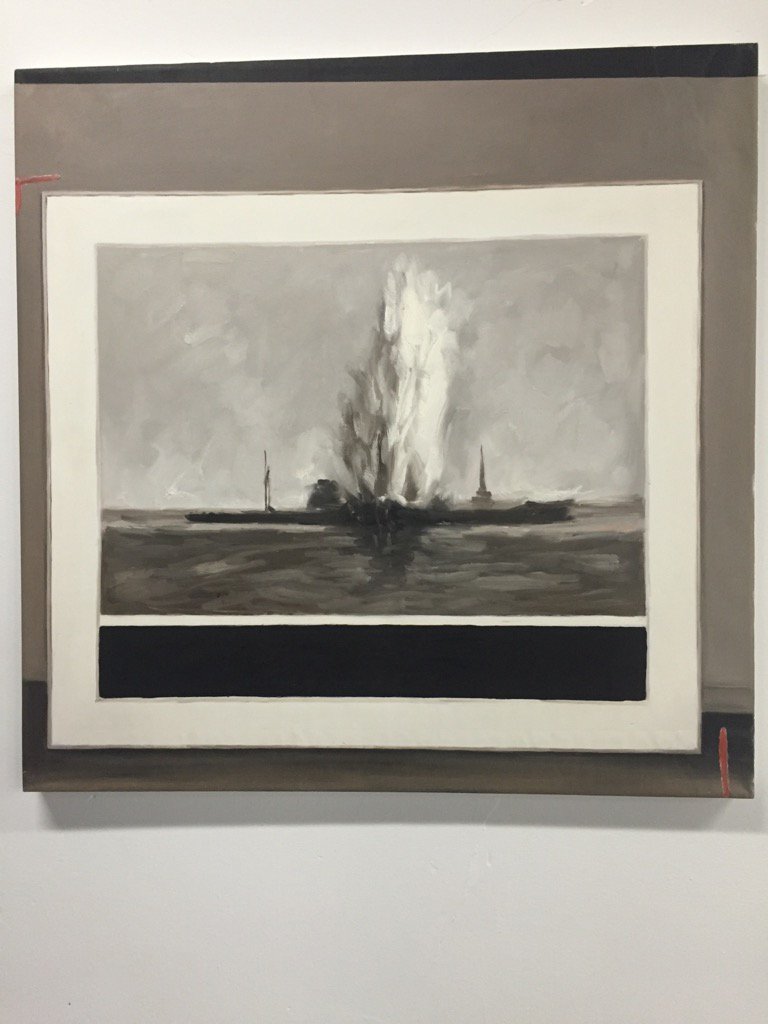

The Glass House is kept pretty much as Johnson left it, and that means almost no art. The Poussin on its stand is the famous exception. But for the first fifteen or so years, there was another work, a small plaster sculpture which sat on the Mies coffee table, and it appears in early photos of the Glass House, such as the 1949 Ezra Stoller image below. It was called La Nuit, and, obviously, it was by Alberto Giacometti. Johnson bought it in 1948 from the artist’s first postwar US show at Pierre Matisse Gallery.

By the mid-1960s, the plaster figure had begun to deteriorate, and Johnson sent the sculpture back to Giacometti’s studio in Paris for repair. The artist’s brother Diego worked on the figure, but Alberto was apparently dissatisfied and stripped it to its metal wire armature in order to remake it. Then he died. That was 1966.

And that might have been the end of it, if independent curator artist Jordan Stein hadn’t gone archive diving in preparation for “Night”. The Times’ Randy Kennedy tells this story of “Night” and La Nuit in a 2012 article which I am trying mightily not to retype from start to finish.

Stein, who worked on “Night” with the Glass House’s curator Irene Shum Allen, found a 1974 letter from James Lord in Matisse’s archive at the Morgan Library, that discussed the restoration of La Nuit. Lord’s idea was to have Diego remake the plaster figure, and then to have it cast in bronze as a posthumous edition that somehow noted both brothers’ involvement. “What would you think of having Diego remake the figure?” Lord suggested. “He-and he alone-could do it so that it would be virtually-but of course not absolutely-as if it had been done by Alberto. Indeed, there are more than a few pieces, if the truth were known, in which Diego had as much of a hand as that…I have spoken of this to Diego, and he would be prepared to do the restoration…Would Annette have to be consulted?”

Which, well, yes, Annette would have to be consulted, though in 1974 she was in no position to decide. I just re-read Marc Spiegler’s 2004 ARTnews article [pdf] on the decades-long conflict among the Giacomettis’ assistants, family, collectors, Associations, Fondations, and Stiftungs that had only then begun to settle down. This seemed like a stretch in 1974, and any possible restoration was mooted by Diego’s death in 1985, and no resolution over its ownership was likely during the posthumous shitstorm over Giacometti’s work. It was basically gone.

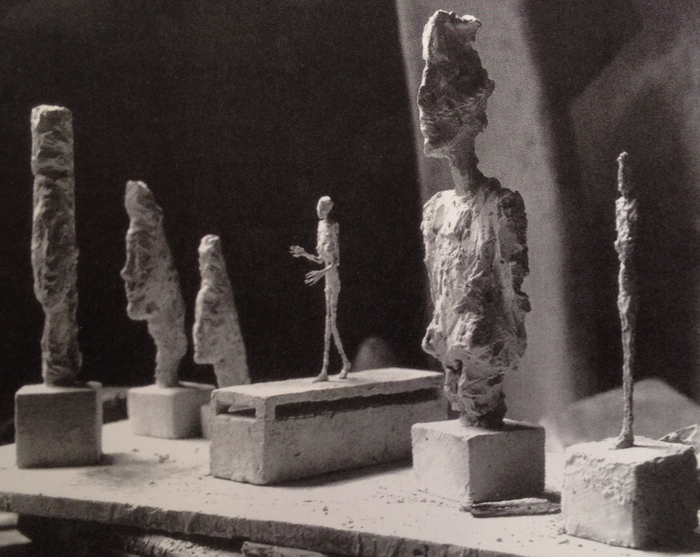

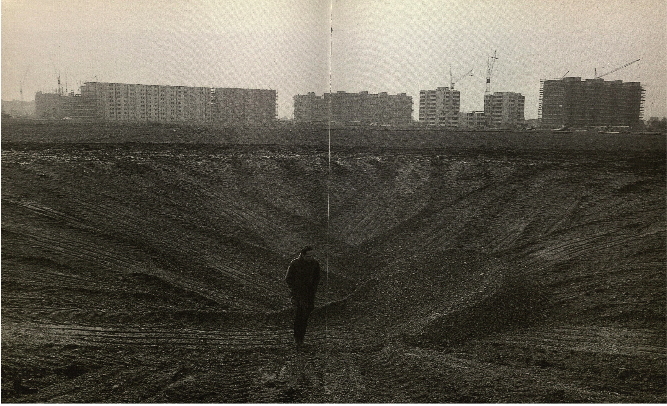

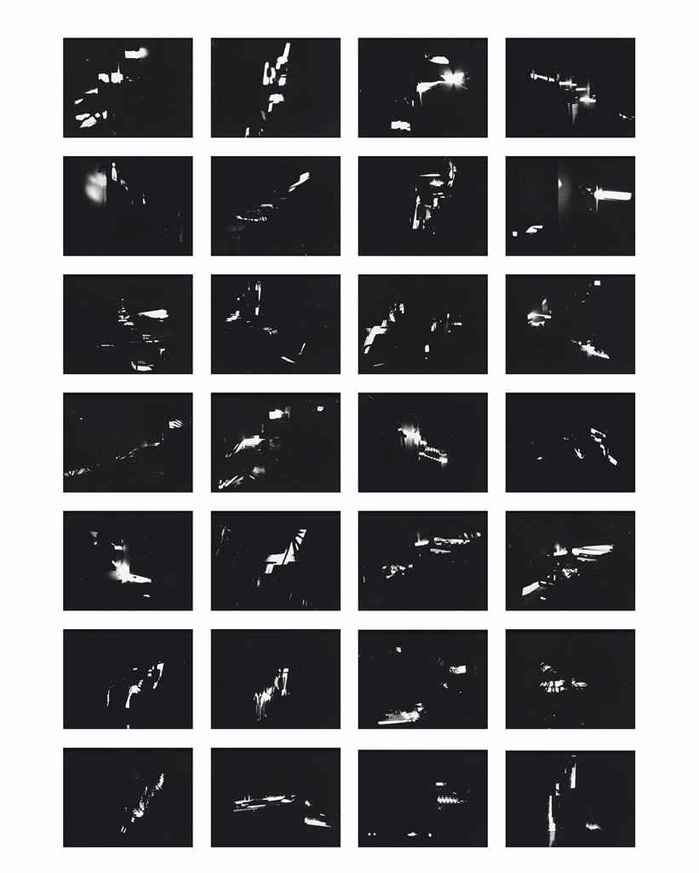

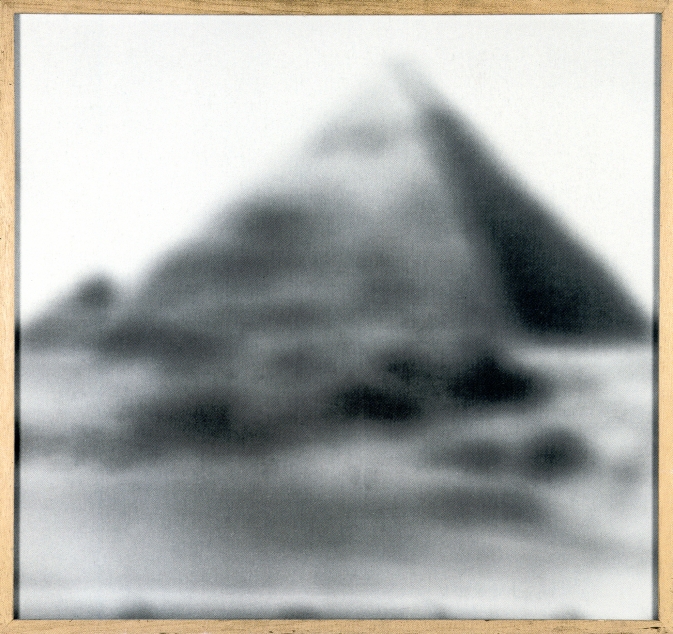

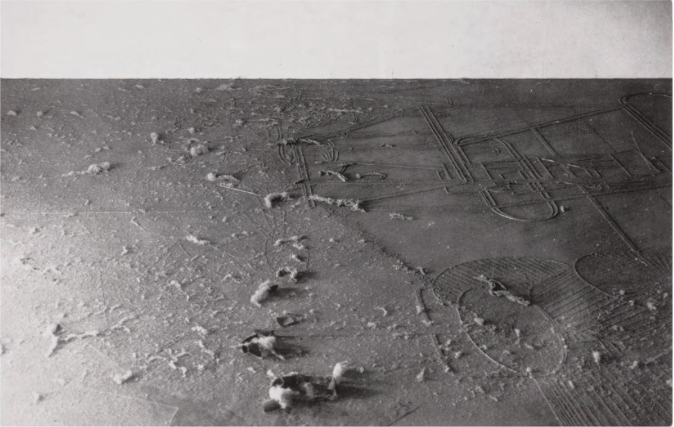

1946 photo of La Nuit, early state, in Giacometti’s studio, by Marc Vaux

Until 2007, when it turned up at the Pompidou in « L’Atelier d’Alberto Giacometti » a show organized with the new Fondation Alberto et Annette Giacometti. The catalogue had 1946 photos by Marc Vaux (above) and Cartier-Bresson of La Nuit in the studio. It was originally a maquette for an unidentified monument and, most amazingly, the walking figure was a woman. Or as Alberto originally put it, “a lanky girl groping in the darkness.” I can’t think of another walking female Giacometti of this postwar style; his attenuated women were always rooted in their spots.

By the time La Nuit was shipped to Matisse’s New York Gallery in 1948, though, it lost its outspread fingers and its “opulente poitrine”; the Pompidou catalogue said it had been “asexualized,” but defeminized or regendered seems more apt, especially in retrospect. Giacometti also made a second maquette La Nuit, with a similar footed platform, but no box base. Both were included in their stripped/deteriorated states at the Pompidou.

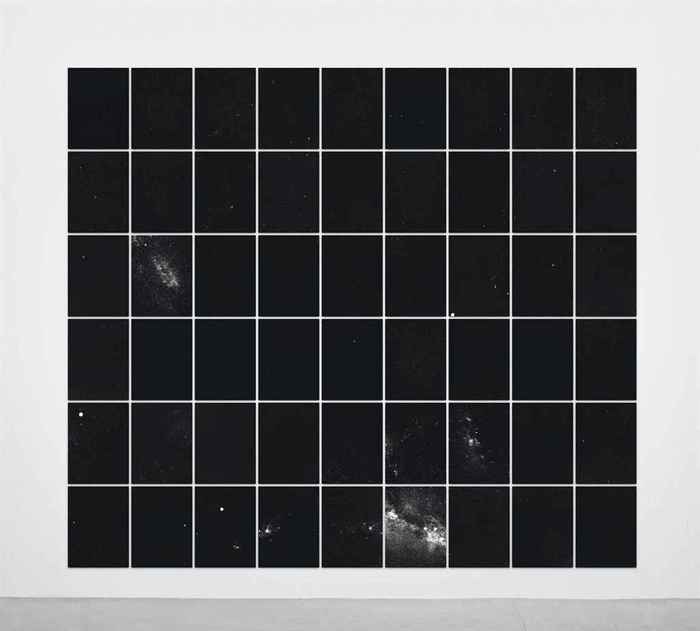

La Nuit original and second version, in current state, from the Pompidou’s 2007 exhibition catalogue

With the bare metal armature protruding from a solid base, Johnson’s La Nuit looked like nothing so much as a World Receiver.

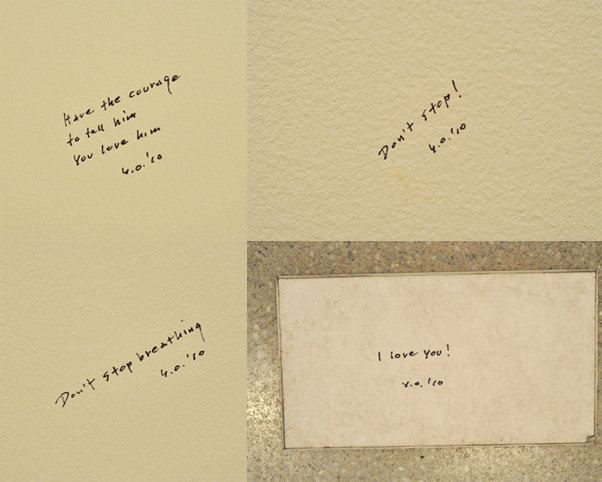

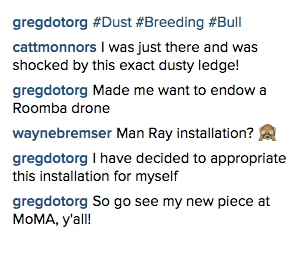

My first comment on Instagram about wanting to donate a vacuum cleaner, but I kept thinking about Matt Connors’ noticing the same ledge situation I had, and having it trigger a similar reaction. After a couple of days, I decided to make the situation a work.

My first comment on Instagram about wanting to donate a vacuum cleaner, but I kept thinking about Matt Connors’ noticing the same ledge situation I had, and having it trigger a similar reaction. After a couple of days, I decided to make the situation a work.