Then please email me if you haven’t already.

greg at greg dot org

Electronic or print, either one. Because I have something for you.

Category: writing

On Size Matters

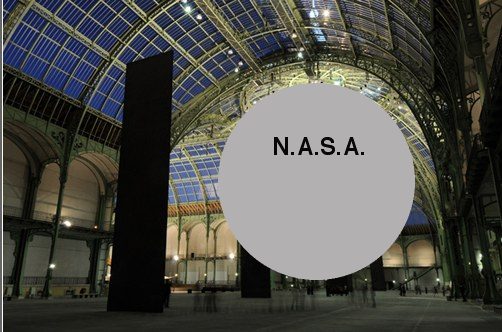

And speaking of Richard Serra. I can’t figure out how James Meyer’s 2004 Artforum essay on the problematics of size in contemporary sculpture got by me until now. It ends too soon, but it’s pretty great.

Beginning with the overwhelming Tate Turbine Hall pieces by Olafur Eliasson and Anish Kapoor, Meyer retraces the history of sculptural size and scale, and how minimalism’s supposedly non-anthropic form was still keyed to the human viewer’s presence. And how post-minimalist folks like Tony Smith and Richard Serra got into, basically, a size arms race, which manipulated the spatial power and experience of the institution instead of critiquing it or fostering self-aware perception. [I’m collapsing a whole lot here. It’s really worth a read.]

Anyway, I mention it now for two reasons, the first being that Meyer begins his history with the 1940s and Abstract Expressionist murals:

SCALE ENTERS THE DISCUSSION of postwar art within the context of Abstract Expressionism. The development of the mural canvas by the late 1940s introduced a bodily scale into painting–a scale that was variously described as one sustained between the painter and the work and between the viewer and the work; on one hand, a phenomenology of making, and on the other, one of perception. Jackson Pollock famously spoke of his drip method as a means to “literally be in the painting.” Mark Rothko noted that he painted “large pictures … precisely because I want to be very intimate and human.” Mural scale was seen as an antidote to the easel scale of Cubism and Surrealism and the illusionism this embodied. As Pollock observed in the same statement. “The tendency of modern feeling is towards the wall picture or mural.”

Which means postwar sculpture and space becomes yet another aspect of the photomural’s history and influence I have to look into.

The other, bigger [sic] reason, though, is Meyer’s articulation of size-ism and awe-based exhibition experience. His is one of the few strongly argued critiques of otherwise-sacrosanct subjects like Richard Serra’s giant torqued sculptures and the museums that fit it, particularly Dia:Beacon and the Guggenheim Bilbao:

Having demanded and inspired the enlarged spaces that museum directors and trustees find it so necessary to proffer, Serra’s sculpture has become the contemporary museum’s major draw, an attraction of sufficient size and impact.

This challenge to the pervasive art world conflation of size, significance, and permanence is basically the context out of which I hatched my own idea to exhibit a Project Echo satelloon in an art space. The problem being, of course, that since all the world’s biggest, newest museums were built to accommodate Richard Serra sculptures, there are less than five venues that could actually show a 100-foot diameter spherical balloon sculpture. They’re just as prone to stylistic and functional obsolescence as a 19th century, fabric-walled salon.

Of course, the real problem is I hadn’t read it, and I really should have.

No more scale: the experience of size in contemporary sculpture, James Meyer, Artforum Summer 2004 [findarticles]

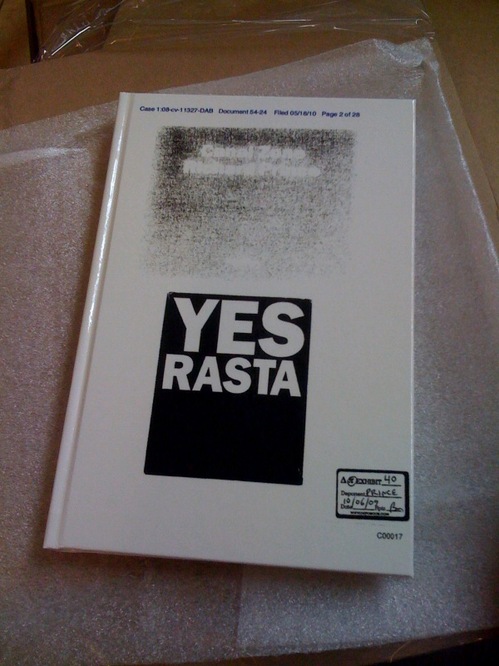

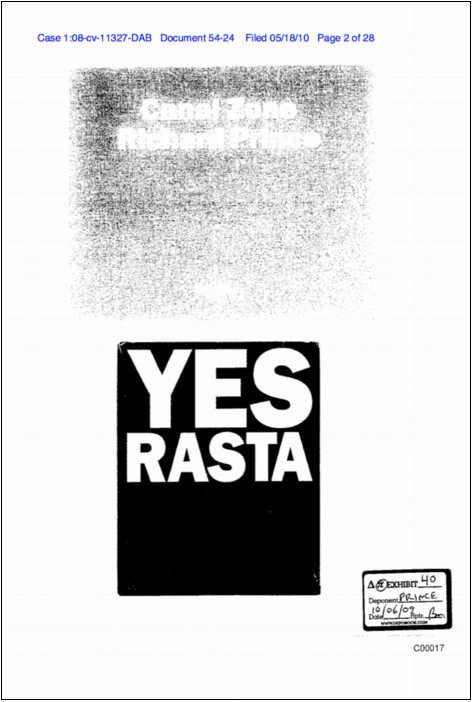

Yes Rasta Indeed.

Another book report just came in, this one from Andy: “Bonus: ups driver was smoking in the truck. Box smells like weed.”

Thanks for partaking!

That’s Where All The Deals Are Being Made These Days

You know how at the end of The Player, Griffin is talking on the car phone to his erstwhile rival-colleague Larry Levy, who’s driving through Century City, on his way to an AA meeting? And Griffin says, “Gee, Larry, I didn’t realize you had a drinking problem?” And Larry admits, “Well I don’t really, but that’s where all the deals are being made these days.”? You know that scene?

Maybe that’s how it was with orgies in the New York art world of the 1960s. They’re just where all the deals were being made.

Here’s an entry from Gary Comenas’ exhaustive and ever-growing timeline on warholstars.org:

c. 1961/62: ONDINE MEETS ANDY WARHOL AT AN ORGY. (PS423)

Ondine:

“I was at an orgy, and he [Warhol] was, ah, this great presence in the back of the room. And this orgy was run by a friend of mine, and, so, I said to this person, ‘Would you please mind throwing that thing [Warhol] out of here?’ And that thing was thrown out of there, and when he came up to me the next time, he said to me, ‘Nobody has ever thrown me out of a party.’ He said, ‘You know? don’t you know who I am?’ And I said, ‘Well, I don’t give a good flying f**k who you are. You just weren’t there. You weren’t involved…'” (PS423)

JANUARY 31 – FEBRUARY 18, 1961: “JASPER JOHNS: DRAWINGS, SCULPTURES & LITHOGRAPHS” AT THE LEO CASTELLI GALLERY.

According to Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol, published in 2009, it was at this exhibition that Warhol first met Johns.

Oh, whoops, it looks like I accidentally cut and pasted part of the next entry in the timeline.

PS423 is Comenas’ own annotation system, a reference to Patrick S. Smith’s 1986 dissertation, Andy Warhol’s Art and Films (Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1986)

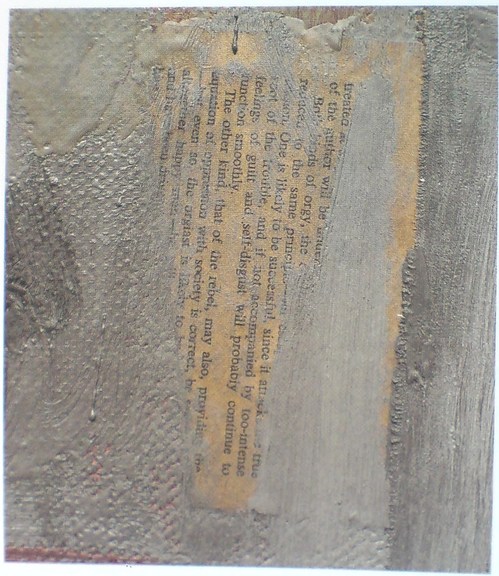

From Jasper Johns’ A History Of Orgies

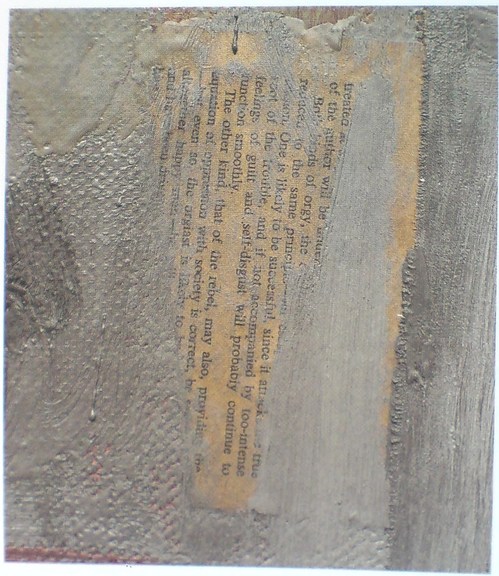

Barbara Rose called this partially obscured page of text “The most tantalizing fragment” visible in Jasper Johns’ 1962 painting, Map, and speculated that it was “probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio.” The visible word “rebel” resonated with Rose’s idea that Map is akin to a battlefield map, and relates to the Civil War, the centennial of which was being commemorated when Johns, who had recently decamped for his native South Carolina, made the painting.

It turns out the page is from the short, 2-page preface to a hardcover, the 1960 US edition of Burgo Partridge’s 1958 book, A History of Orgies. I bought this book, which is basically one Oxford student’s quick tour through the dirty parts of the classics, followed by a brief history of sexual excesses and hypocritical moralizing in Europe, ending with a call to keep pushing modern society toward a Greek ideal of a sensible, guilt-free sexual culture.

A History of Orgies was apparently a good-, if not best-, seller, both in the UK and the US. After buying a copy online–strictly for research purposes, you understand–I skimmed through it. What I don’t know about orgies could fill several books, but its argument, even its thesis, frankly, seems a bit scattershot. Perhaps more lucid syntheses of orgies have followed Partridge’s? I’ll wait for the orgiast literati to chime in. But it was impossible for me to read the preface without thinking of it in terms of Johns’ work, and also his life in 1960-62, and the culture around him.

Rose calls the visible phrases “chosen and deliberately revealed,” and says they “participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter,” which is a kind of hilarious image, given the actual source of the text.

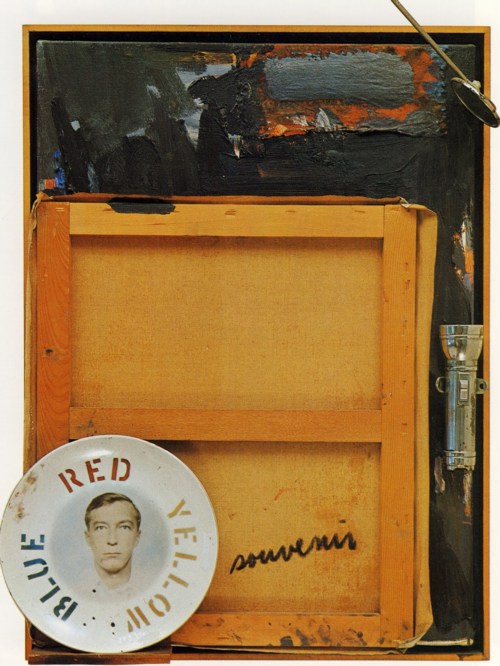

And just as the brushstrokes teasingly obscure some of the text, I also can’t help wondering what’s behind, what we can never see: the other side of the page. There are at least three Johns works from this period–Canvas (1956), Fool’s House (1962), and Souvenir 2 (1964, below)–where the artist affixes smaller canvases face down on his larger work, depriving the viewer of knowing what lies underneath. I have no idea if there’s anything in the first page of Partridge’s preface that Johns wanted to not-show, but the full text of what he ended up not-showing is below.

Souvenir 2, 1964, which was in the Ganz collection until 1997 excellent discussion at Christie’s

In the previous post, I referenced the skepticism, voiced by Yve-Alain Bois, of the usefulness of identifying [and thus being tempted to interpret] all the raw materials in Rauschenberg’s combines. It’s not like there’s a unifying, hidden message, a Rauschenberg Code, waiting to be deciphered by some future Tom Hanks. But technology is rapidly making the once-impossible trivial, and art from the past is going to have to deal with it. It took me only a couple of Googling minutes to identify a text that Rose could only speculate on–and which Johns, if he ever meant for it to be identified, has certainly not discussed.

But this impact of instant, ubiquitous information reminds me of how Land Art, once intended to be remote and highly inaccessible, if not impossible to find, ends up on GPS systems and Google Maps. The times, they’re a-changing.

Anyway, ladies and gentlemen, the preface to Burgo Partridge’s A History of Orgies with pagination intact, and the texts visible in Johns’ Map in italics:

The Orgies Of Art History

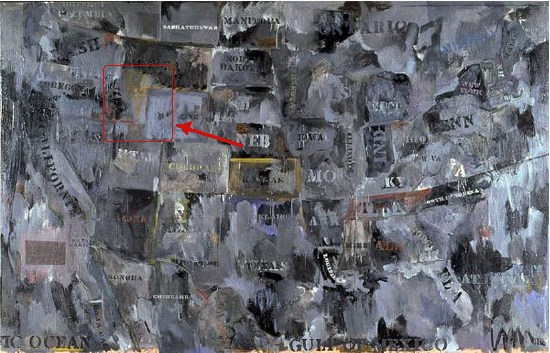

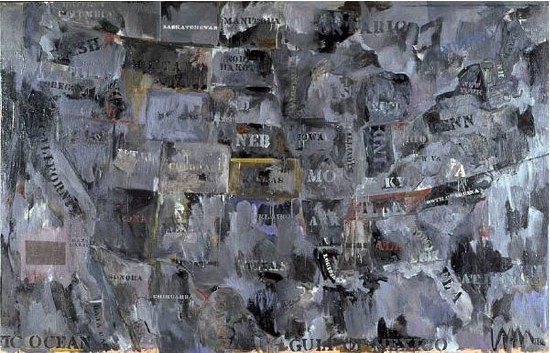

Map, 1962, Jasper Johns, via moca.org

For her contribution to the Jasper Johns Gray (2007) catalogue, Barbara Rose writes about the history and significance of Map, 1962, the artist’s first big, gray masterpiece. Johns made it to raise money for his new Foundation for Contemporary Arts, which was founded to stage some performances of Merce Cunningham. Marcia Weisman bought it out of Johns’ studio and ended up leaving it to MoCA.

Rose suggests that Johns’ Map paintings are akin to battlefield maps, and that the gray one, in fact, resonates with a particular Civil War battle, the Battle of Antietam. She cites Johns’ own South Carolina upbringing, the centennial commemoration of the Civil War that was in the news in 1960-2, and a series of paintings by Frank Stella which drew some of their titles from Civil War battlefields. [Rose was married to Stella at the time, of course, and also refers to one diptych from the series titled Jasper’s Dilemma.] Also, Rose writes, “The difficult realities of Johns’s personal life coincide with the idea that this map pictures a battlefield.”

After recounting some formalist skirmishes with General Clement Greenberg’s troops, Rose zooms in on the surface of the painting and on some of the collaged elements in Map that Johns intentionally left visible:

Topographically, the hills, ridges, and ravines of Johns’s gray Map suggest geological strata bursting. Paint washes over the surface like sea spume or waves eroding coastlines. Known borders are changed or blurred. This transgression of boundaries is a physical fact of art historical as well as personal significance. The surface is scarred and scraped in areas so that the printed matter sealed into it with adhesive encaustic is visible. The most tantalizing fragment is not newsprint but part of a page, probably ripped from a paperback book Johns had in his studio. One can make out the words “intense feelings of guilt and self-disgust,” as well as “rebel” and “orgiast.” These chosen and deliberately revealed phrases participate in Johns’s game of peekaboo, which he plays with his audience, much as a stripper suggests that more will be revealed with each succeeding fan flutter.

Map detail, via Jasper Johns Gray

Lots of interesting stuff, but I am most fascinated by the overall strategy Rose adopts, of floating the connection to “the difficult realities of Johns’s personal life,” and then going both wide and deep about everything but.

Publishing A Book? Check Your Wok

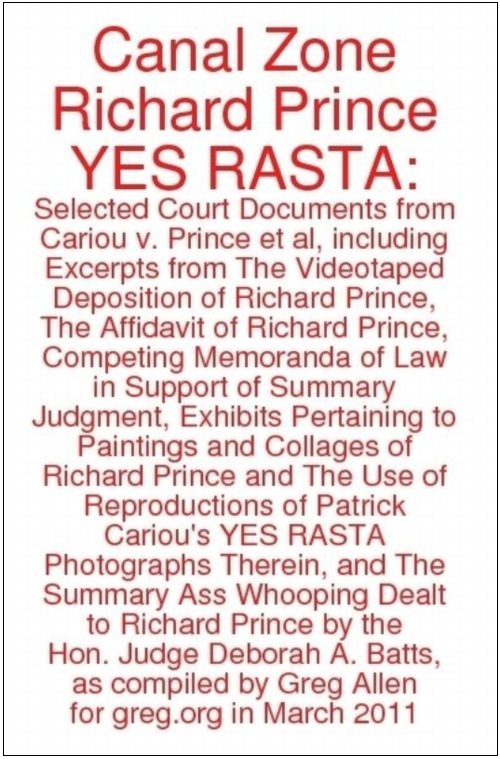

So I try to create a book with as little creative alteration as possible, to hew as closely as I can to the court documents themselves, without changing, editing, or annotating them at all.

OK, so I weave images from the exhibits they’re discussing into the sections of the transcript where they’re discussing them. And–NO design–I only use Preview’s default annotation settings–giant, red Helvetica–to create the headings, and the table of contents, and the cover.

OK, so I have to cheat a little to get the cover to work, so I do end up re-keying the cover in the cover wizard, so that it matches the annotation typeface. But that is IT.

And what happens when you are aggressive about not trying to create an aestheticized object–or rather, to create an aestheticized object that looks like you did nothing aesthetic to create it? When you try to write less than a hundred words total, including your self-consciously long title?

Well, we can ask Brett in Miami. He’s the first one who spotted three–three!–typos on the back cover of the softcover edition. Well, he’s the first one to let me know he spotted them, anyway. And for that I thank him.

I corrected two immediately, and I’m still pondering about the third: “…it is intended to serve as an art historical and critical resource, filtering relevant primary information about Prince’s biography, practice and wok…”

I mean, couldn’t it stay? “Oh, Richard Prince, I love your wok!” Maybe it’s the t-shirt.

update: here’s the link to the new printer, where you can buy the expanded edition in softcover.

Size Matters?

As I have tried to make sense of the Cariou v. Prince decision, to figure out how Judge Batts found it so easy to dismiss Prince’s detailed explanation of his transformative ideas and process, I can come up with two possible rationales.

One is the distinction absolutely no one except Prince–Cariou, the judge all the lawyers, including Prince’s and Gagosian’s–makes between photographs and images, reproductions in a book. It’s one of Prince’s consistencies that reveals itself throughout his deposition and affidavit. [Always be selling!]

And it’s a point that Joy Garnett makes very cogently in her editorial in artnet which looks at the difference between mass produced images and fine art objects.

The very existence of Prince’s “Canal Zone” series is apparently now in peril, in part because no one seems to be able to tell the difference between a painting, which is a one-of-a-kind object, and a photograph, which is by definition mass-producible.

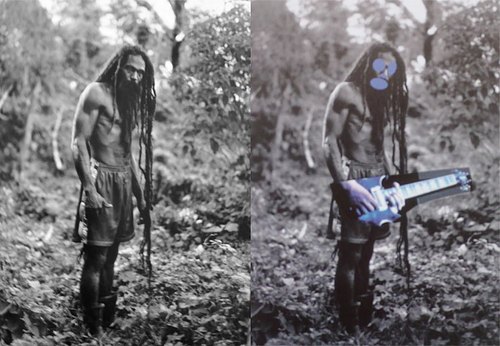

The other distortion I see is scale. Patrick Cariou and his lawyers prepared an exhibit [it’s in the book, $25 hardcover, $16 paperback!] detailing all the Yes Rasta images Prince used, in whole or in part, as source material in his paintings.

Photocopied side by side, the book pages and paintings can seem remarkably similar, even interchangeable. The comparison images that Cariou and friends released to the press are even more persuasive. But if this isn’t technically deceptive, it certainly obscures the scope of Prince’s transformations.

Cariou’s book is 10×12 inches. Prince’s paintings are 6-12 feet. Graduation, the painting made by altering the coloring of Cariou’s image, reprinting it, painting and collaging it, rescanning it, cropping it, inkjet printing it onto canvas, and then overpainting and collaging it again, is 5×6 feet. A more accurate side-by-side comparison would look like this:

These details of size, color, cropping, and format might seem like minutiae. But they are also exactly the kind of transformational changes cited by the judge in Blanch v. Koons. More importantly, they map directly to the decisions Cariou used to describe his own creative process–and they were also cited by the judge in declaring Cariou’s work “highly original.”

Maybe if the judge had compared object to object instead of image to image, she might have found Prince’s efforts a little more worthy of copyright consideration. In their filings, Prince and his lawyers repeatedly invited the judge to view the paintings themselves, either in Prince’s studio, or in a gallery or other space in town. It does not appear that this happened. But maybe she looked at Cariou’s exhibit, and figured she didn’t need to see anymore.

From The Department Of Corrections: Archivists Do Not Find My Anecdotes Amusing

I guess if you think about it, archivists really wouldn’t think it’s exciting, or even that amusing, when you tell a story that wrongly makes it sound like they’ve been taking smoke breaks for 25 years, leaving their random blogger patrons to discover lost art treasures under their noses.

But that is apparently how my post a couple of weeks ago about opening an unprocessed box of archival material from the Alan Solomon papers sounded to Barbara Aiken, the Chief of Collections Processing at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.

Fortunately, she was kind enough to correct my errors, chief among which is the implication that the box I found some Jim Dine drawings in had not, in fact, been sitting unprocessed in the Archive for 25+ years; it only came in in 2007, and they are, in fact, getting to it.

On this error and the larger issues of archive processing and of artworks inside the archives, Ms. Aiken graciously sets me aright, and for that I thank her and her most professional, capable colleagues.

Previously: from the mixed up files of basically everyone [except the people who leave their papers to the AAA, where they are very well looked after and made accessible]

Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Sample Spreads

Thanks for the support and feedback on the Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents &c., &c. book. [updated link info below]

Some folks who ordered the electronic version–the first to get the compilation in their hands, since the print editions take a few days to arrive–have emailed wondering where “the rest” of Richard Prince’s deposition transcript is, because there are gaps and missing pages.

That’s exactly right, and it’s why I decided to make this thing in the first place. As far as I can tell, the entire 378-page transcript of the 7-hour deposition was not entered into the court record, only the excerpts that pertained to quotes or points referenced in the two sides’ various legal motions. As I was reading those scattered snippets in various places in the court record, I realized it would be more useful to have a single compilation of all Prince’s testimony. And it’d be easier if it was in order. So I took apart the pdfs and sorted the pages, then interlaced the other exhibits [i.e., images from Cariou’s book and Prince’s show and catalogue] as they came up in the course of testimony.

Here are a couple of sample spreads taken from my original [sic, heh] pdf. There are about 250 of these transcript pages in total, four per printed/pdf page.

pp. 125-8, 149-152

pp. 178-181 and Exhibit 15, installation shot at the Eden Rock Hotel, St. Barth’s

APR 2011 UPDATE: Here is the link to buy the new, expanded edition, which includes Prince’s entire deposition transcript–an additional 101 pages–plus other key legal documents. It’s a new printer, and the finish of the book is nicer, I think.

Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: The Book

from greg.org: Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents, &c., &c. in

hardcover, 290pp. $24.99 [updated link info below]

Because really, why not?

It’s always bugged me when I read a news story about a legal case, or a scientific report, and there’s no link to the original source material. And since I’ve been quoting from them a lot lately, I have been fielding a lot of requests for copies of the court filings and transcripts in the Patrick Cariou vs. Richard Prince & Gagosian case.

It was yesterday afternoon, though, when I was sending my fourth email [or eighth, since the attachments are so big] that I realized Richard Prince’s deposition is not only the longest interview he’s ever given, it’s probably the longest interview he’ll ever give. [Go ahead, Hans Ulrich, you just try!]

I mean, seriously, the guy talked for seven hours. Under oath. In insane detail about his work, process, and ideas. Granted, he was being grilled by a guy whose art ignorance is only surpassed by his obvious contempt for Prince, a lawyer who can’t tell a photograph from a painting from a reproduction in a book. But still, he got Prince talking.

And Prince was surprisingly [to me, anyway] and admirably consistent and credible, at least in terms of his work. Yeah, it’s a nice bit of fact-checking trivia to strip away the coy mystery crap that surrounded his Guggenheim retrospective: Prince testified that he is Prince, and that he did live in the Panama Canal Zone, but only as a very young child.

But I found his explanation of his early formative inspirations, particularly Warhol and punk rock, to be both relevant and sincere. The deskilling argument that you could pick up a guitar for the first time, and by the end of the week, go up on stage and perform, with visceral effect, sounds real to me. It makes sense, at least in its own context [and in my own high school experience.]

The cover of the paperback edition includes the full title. 290pp 376pp, $17.99

Anyway, Prince’s entire deposition transcript has not been released [update: it has now; see below], but a patchwork of 250 or so pages out of about 375 were attached as supporting documents to various filings and motions in the case. So I sifted through and pulled them all out, and then placed them in numerical order. There are a lot of gaps, of course, and legalistic joustings, but there’s a lot of information, too.

Combined with his 28-page affidavit, it really is the most extensive discussion of his work, practice and biography I’ve ever seen Prince make. The fact that it’s all coming out in the context of a copyright infringement lawsuit is really too perfect to pass up.

Into this I wove the major documents and exhibits Cariou’s lawyers discussed with Prince: all the Canal Zone series paintings; installation shots from the Eden Rock hotel in St. Barth’s; Prince’s “Eden Rock Pitch,” a rough movie treatment whose characters and story fed into the paintings; and Cariou’s extensive visual comparison of Prince’s Canal Zone paintings and the YES RASTA images that ended up in them.

And for good measure, I added both sides’ memoranda, where they make their fullest legal arguments for their fair use/transformative use and copyright infringement positions. And of course, I included Judge Batts’ ass-whooping of a ruling.

In all, 290 pages, all taken–appropriated, one could say–from the court record, but organized into a clearer, more readable format. And with a focus, not on an exhaustively documenting the case itself, but on Prince and his work.

If you were to download all of this material from pacer.gov, it’s run you upwards of $24 [$0.08/page]. And then you’d still have to sort it all out. For that money, I thought, you could have a nicely printed book. And so that’s what I did.

There are hardcover and paperback editions, and electronic copies, too, which I haven’t tested yet. I’m still tinkering with the cover design. Both versions are included inside the book, as frontispieces or title pages or whatever, but right now, the b/w cover cover is on the hardcover, and the red, made-with-Preview’s-default-annotation-settings version is on the softcover.

This is definitely an experiment, so any and all feedback is welcome. But if you’re looking for the perfect book to take to spring break, or to class up your summer share, then you have come to the right place. Enjoy!

Buy your own copy of Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents, &c., &c. in or in paperback [$17.99]. [createspace.com]

hardcover [$24.99]

APR 2011 UPDATE: OK, the response to this book really caught me off guard, so I’ve done some more work on it. The new, expanded edition now includes Prince’s entire deposition transcript, an additional 101 pages of testimony not previously released publicly, and several additional key legal documents from each side. In addition, while lulu.com was a quick and decent way to release a book almost instantly, I decided to switch to a higher quality printer for the new edition. The facsimile pages are a little smaller, which I’m still working on, but the quality of the book is noticeably higher. It now clocks in at 376 pages, for $17.99.

Richard Prince Decision? You’re Soaking In It!

What with all this Prince in my head, I start seeing and reading and remembering things in relation to the Canal Zone case. For instance:

In conjuring up a meaning for Richard Prince’s Canal Zone work that fit the crime she was convicting him of, Judge Batts cited part of a 1978 essay on Appropriation Prince wrote, which he was asked about in his deposition. 1978!

I feel that I like to get as much fact into my work and reduce the amount of speculation. I believe there’s too much–I like an artwork where that when you see something, like a cowboy or a girlfriend, I mean these are, in fact, true.

Batts decided that this meant Prince appropriated Patrick Cariou’s photos because he was trying to convey the same “core truths” about Rastafarianism as Cariou. But it actually made me think of a quote from Greg Foster-Rice’s essay in his just-released anthology, Reframing the New Topographics, where he discussed the influential early 70s photography show in terms of systems theory, and in particular the system of photography itself:

Photographs, in other words, are distinct from other forms of representation in that their connoted messages are built upon a widely held belief in the medium’s denotative status as an almost perfect copy of the real.

I have to say, I really hated Canal Zone when I first saw it, but the more I study and think about it, I’m coming around. In one sense. Prince was making paintings about photography, and about the different expectations of truth and subjectivity, fact and fiction, each medium embodies. Which is nice.

Then there’s the kicker from Steven Stern’s review of Spiritual America: The Guggenheim Retrospective in Frieze:

Perhaps the key joke for the retrospective is one that appeared in several different paintings: ‘Man walking out of a house of questionable repute, muttered to himself, “Man, that’s what I call a business … you got it, you sell it, you still got it”.’ A museum is, after all, a house meant to settle questions of repute. And this particular museum exhibition was, among other things, a comment on Prince’s clearly impressive ‘business’. Like the one described in the joke, this industry depends on a seemingly magical economy: the slippery way that things that aren’t exactly objects – such as images and sex – get valued. Prince is a connoisseur of such economies. For better or worse, no matter how much he’s sold, he’s still got it.

That is just awesome.

And last but certainly not least, is Pablo Picasso, who Prince cited repeatedly as a model and an inspiration for his work. This quote is from an awesomely forthright talk Frances Stark gave at Mandrake Bar in LA in December 2009 as part of the Contra Mundum series. Ro/Lu, you’re off the hook, but the rest of you out there, are in deep trouble for not telling me about the published version of Contra Mundum I-VII. I’m the big man, need the info. Anyway, Picasso:

“But of what use is it to say what we do when everybody can see it if he wants to?”

The Good Wife

You know, I tried. I really tried, but there just are not enough hours in the day. You can all take down David Colman’s John Currin & Rachel Feinstein Style section article yourselves. Lord knows everything but the headline–“Their Own Best Creations,” which at least gives a nod to the existence of artifice, spin, image management, the subjective construction of the self–is ripe for the kicking.

I will say that it’s the conveniently swattable straw men that bugged me the most. The specious [or is it?!] notion that “the art world” somehow punishes those artists who aspire to–or even approach–their collectors’ lifestyles. When, in fact, “the art world,” such as it is, is all but obsessed with art’s wave/particle-like duality, its near-magical power to transform culture into capital and vice versa.

The art world has been laboring mightily for decades to accommodate and cater to the needs, desires, lifestyles, and politics of wealth-flaunters, hyper-capitalists, and consumptionists of all kinds, and it pisses me off to see all that hard work go unrecognized by the Style section, of all sections!

The idea that Currin and Feinstein’s conservative political views somehow transgress anything but the feeblest cliche of liberal “art world” orthodoxies. I guess it’s the notion of “an” “art world” that’s so easily thwarted by John & Rachel’s unabashed fabulousness that really gets me.

Such an art world is a fairy tale. There are also more art worlds, and a far greater range of political views within them, than the Style section cares to acknowledge. I can think of a dozen conservatives–even some card-carrying neo-cons–who are prominent, active participants in New York City’s art scenes: artists, dealers, and curators, too, not just collectors or museum people. This heterogeneity is who “we” are, and to pretend otherwise, or to ignore these differences is willful or naive, or both.

Or maybe it’s that political differences in “the art world” have long been tolerated, negotiated, or if need be, consciously set aside or even suppressed in the interests of achieving an art-related goal. And really, are there any political chasms that can’t be bridged by Blanchette Rockefeller’s noble response to questions of whether his years as an enthusiastic Fascist activist might preclude Philip Johnson’s election as a MoMA trustee: “Every young man,” she reportedly said, “should be allowed to make one very large mistake.” I’m sure it works, try it at home!

As for Rachel’s work, and her career, and the inevitable comparison to her husband’s, how can it not be eclipsed? Is it apparently impossible to say that? But what is Rachel to do? Not show? Not make? Show under a pseudonym? Is it impossible to wonder if Rachel’s career differs from John’s because of her medium? Or her content? Or her concept? Or her gender? Was it “being that glamorous” that caused Feinstein to “take [her] eye off the ball” over the last few years, Jerry? Might having and raising three kids play a part? Maybe what Rachel’s career is really missing is a good wife.

From The Mixed Up Files Of Basically Everyone

What’s that, dear? Oh, nothing, just some legendary but unknown drafts for the first film adaptation of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, by veteran Hollywood screenwriter Benjamin Hecht.

After reading various references to the early 60s script, Jeremy Duns decided to go looking for it, and whaddyaknow, there it was, sitting in Hecht’s archive, which is at the Newberry Library in Chicago. Apparently, in the intervening decades, no one had ever bothered to actually look for it:

[T]hese drafts are a master-class in thriller-writing, from the man who arguably perfected the form with Notorious. Hecht made vice central to the plot, with Le Chiffre actively controlling a network of brothels and beautiful women who he is using to blackmail powerful people around the world. Just as the theme of Fleming’s Goldfinger is avarice and power, the theme of Hecht’s Casino Royale is sex and sin. It’s an idea that seems obvious in hindsight, and Hecht used it both to raise the stakes of Fleming’s plot and to deepen the story’s emotional resonance.

It’s exactly the kind of mind-boggling, serendipitous archive find that keeps me going on this Johns Flag hunt, even when the more skeptical part of me is saying, “Seriously, how could Jasper Johns’ first flag painting have been stolen, and missing, and then resurface in his own dealer’s office, and then disappear again, and no one knows where it is or even what actually happened to it?” But the more I dig and ask around, the more I find that, though plenty of people gossiped or speculated, almost no one has ever actually searched for it.

UPDATE/CLARIFICATION/APOLOGY/&C. Ha, ha, I guess if I think about it, yeah, my meant-to-be-exciting-thrill-of-discovery-in-uncharted-archives anecdote below could make actual archive professionals cringe. And I guess I didn’t think of that. OR mean it as any kind of criticism of the way the AAA works, just the opposite, in fact.

Fortunately, Barbara Aikens, the Chief of Collections Processing at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art took the time to correct some inaccuracies and clarify some of the wrong implications in my account. Which, I didn’t really– I mean, it was really meant to be kind of an amusing offhand story, not a transcript, which– Anyway. My bad.

A few trips ago, while researching at the Archives of American Art, I opened a white cardboard box, indistinguishable from all the others on the outside. But instead of the neatly labeled, acid-free folders, I faced a mishmash of giant envelopes, ragged edges, and old, manila folders. And a rubber banded brick of old AmEx bills. And some matchbooks. What a mess. It was more time capsule than archive.

In the middle of a sheaf of clippings and tear sheets, interviews and reviews and feature articles about Robert Rauschenberg, I came across an odd little card. No, it’s a transparency showing an Apollo alnding capsule. No, there’s three. Blue, magenta, cyan, waitaminnit, this is taped together by hand. It’s an object, maybe even a work, made of layered transparent sheets, similar to Rauschenberg’s editions made from multiple sheets of plexiglass. Shades (1964) is one; I have a similar set of plexi discs somewhere from 1970-1, in a boxed set of multiples titled, Artists and Photographs. Here you go: Revolver.

The other day, i recognized that space capsule image as the one in the Hirshhorn’s big Rauschenberg screen/painting, Whale, which is also from 1964. Maybe Bob sent that little objet home after a studio visit or something. But should it really be in here, in the archives, hanging out with greasy-fingered riff-raff like me? Maybe I should say something.

A couple of folders later, I carefully extract a large, tattered, manila envelope with something about a group show or benefit scribbled on the outside. The first thing I pull out is a signed Jim Dine drawing. Then another. The next one is an Oldenburg. I pull out a piece of black paper, which turns out to be a chalk drawing. A little dust gets on my hands. At which point–I mean, fingerprints, right? I’m totally busted–I call the attendant over with a hearty, “Uh, did you know there’s a bunch of original art in here?”

No, she did not, but yes, that happens, because, in fact, budget, priorities, low demand, &c., &c, some of this collection’s boxes had not been processed yet. I was probably the first person to even look through this box since it had come in over 25 years earlier. She gave me a stack of acid-free paper to slip in between the various drawings, and I decided that, though it looked like a blast, the stuff in the packet was obviously not related to my research–at the very least, if Johns’ Flag had been stuffed inside, I would’ve seen it–so I put it all carefully away.

I guess I’m just saying, there’s stuff out there. And no one’s been looking for it, so get cracking.

UPDATE I thought I was being helpful by not identifying the collection I was using here, but of course, Barbara knew right away what it was: the Alan Solomon Archives. The Solomon material had come into the AAA in waves, and the unprocessed box had actually entered the Archive in 2007, not, as I misunderstood, 25+years ago.

The presence of art, drawings, sketches, etc., while not a collecting goal of the Archive, is also not unheard of, and such material typically remains in accessible within the collection, where it is to be handled with care.

Barbara points out that while I made it sound like there I worked through a stack of acid-free paper, in fact, I only inserted three sheets between a couple of drawings. This is true. I was given a stack, but after replacing the works I’d taken out, I figured I’d leave the rest of the handling to the professionals, and so I closed up the box.

On the point of processing, I can’t do better than Barbara’s statement:

On average, we process and preserve about 500-700 linear feet per year; this includes writing full and detailed electronic finding aids that are available on our website. In addition, we are the only archival repository in this country that has a successful ongoing digitization initiative to digitize entire archival collections, rather than just selected highlights from collections. To date, we have digitized well over 100 collections, totaling nearly 1.000 linear feet and resulting in 1.5 million digital files. Archival repositories from across the country regularly consult with us on our large scale digitization methodologies, work flows, and infrastructure.

I would hate to think that users will think less of our major efforts here at AAA to increase access to our rich resources, or, worse, think that we do not care about the stewardship of collections. It is one of our ongoing mission goals and we devote considerable staff resources to our processing work. However, the work is never done to be sure.

And thank you for it. And for the clarifications. Carry on.

Casino Royale: discovering the lost script [telegraph.co.uk via daringfireball]

‘Do-It-Yourself Existential Individualism’

Frieze’s 20-year retrospective of itself continues apace, and wow, it’s like running into an old flame on a train platform.

I hadn’t thought about Daniel Birnbaum’s 1996 essay, “IKEA at the End of Metaphysics” in years, but wow, it’s just all flooding back.

From a Heideggerian perspective IKEA best sellers such as ‘Billy’, ‘Ivan’, and ‘System 210’ do not represent a corruption of everyday life, but have merely formalised what is already there; the IKEA catalogue only makes the tendency towards uniformity more conspicuous. Heidegger’s global ‘levelling’ is not a critique of the common forms of everyday life as such, but of their passive acceptance. At the end of metaphysics, levelling is complete – no one questions the catalogue.

Obviously–well, now it’s obvious, anyway–my own Ikea X Enzo Mari mashup project has its origins in the critical perspective of the company and its ideology which Birnbaum mapped out 15 years ago, and which I absorbed.

Also, I’m reminded how I miss Jason Rhoades.

IKEA at the End of Metaphysics [frieze.com/20/ via ronald jones]