Johns, Flag: “American artist Jasper Johns has produced a distinguished body of work dealing with themes of perception and identity since the mid-1950s.” –whitehouse.gov

I’ve been trying to get a better sense of the first decade for Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit, from the mid-1950s, when it was made and first shown, until 1965, when the Jasper Johns Flag was removed from the work which had originally been titled, Construction with Jasper Johns Flag. It happens to be the time when both artists’ careers skyrocketed; when their intense personal relationship flourished, then fell apart; and when they were creating arguably their most significant works. And one of the people who was there for all of it was Alan Solomon.

Solomon was a curator and friend of Leo Castelli; he showed both Johns and Rauschenberg–including Short Circuit–in March 1958 at Cornell University’s White Art Museum. More on that later.

After he moved from Ithaca to the big city to run the Jewish Museum, Solomon gave Rauschenberg his first solo museum show in 1963. And he did the same for Johns in 1964. And he curated both artists into the US exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1964, which erupted into controversy when Rauschenberg won. [The controversy was nominally about the eligibility of the US show, which was mostly installed in the former American consulate next to the Guggenheim, and only partly in the US Pavilion. But basically, it boiled down to Europeans being pissed at the American bad boy winning. I think.]

Long story short, Solomon was a key, early supporter of both artists’ work, and throughout the 1960s, he regularly made the argument that Pop, which he was also instrumental in promoting, was born directly from the work of this pair of “germinal artists” Rauschenberg and Johns.

Which is funny, because reading through Solomon’s texts, speeches, and interviews, you wouldn’t know Johns and Rauschenberg were even dating, much less spawning heirs. Though he showed the collaborative combine painting itself in 1958, Short Circuit is completely absent from Solomon’s exhibitions, texts, and interviews in 1963, ’64, and ’66.

What is present, in catalogue essays for both artists, is Solomon’s repeated and unequivocal rejection of the personal, the emotional, the biographical, the expressive, almost any type of subject or subjectivity at all, in fact, in their revolutionary work.

Looking back at the critical content closet Solomon constructs around these artists and their work–constructed with, you have to assume, their blessing and even active involvement–it’s tempting to take everything he says and simply invert it, and feel like you’re getting a clearer picture of what’s going on.

When Solomon writes of the importance of “other possibilities” to appreciating Johns’ Flags, while explicitly excluding the possibility of any personal associations, it almost seems like an invitation, a demand to consider them in an autobiographical light, as a kind of silent self-portrait. Which becomes very complex very quickly when the germinal Short Circuit re-enters the mix.

But I still have to figure out how, what, or whether to write about that head-on.

For right now, here are a couple of excerpts from Solomon’s catalogues for each artist. Johns first:

Category: writing

Richter’s Balls, Regrets

So I’m reading along in my new copy of Gerhard Richter: Writings 1961-2007–which is pretty awesome, and which does appear to supersede the artist’s previous collected writings, The Daily Practice of Painting, which is good to know, but really, what to do with all this information?–and I come across this discussion of glass and mirrors and readymades in a 1993 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, and I’m like, holy crap!

When did you first use mirrors?

In 1981, I think, for the Kunsthalle in Dusseldorf. Before that I designed a mirror room for Kasper Koenig’s Westkunst show, but it was never built. All that exists is the design–four mirrors for one room.

The Steel Balls were also declared to be mirrors

It’s strange about those Steel Balls, because I once said that a ball was the most ridiculous sculpture that I could imagine.

If one makes it oneself.

Perhaps even as an object, because a sphere has this idiotic perfection. I don’t know why I now like it.

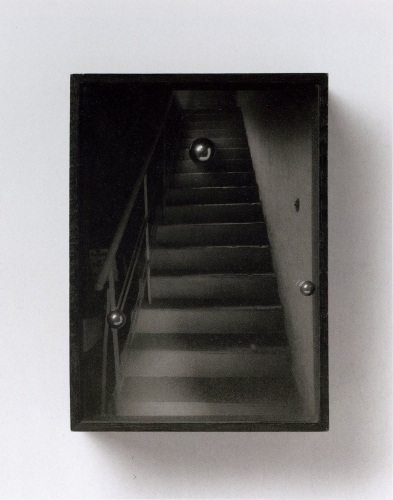

Richter’s mirror Steel Balls? Whew, never mind, they turn out–I think–to be Kugelobjekt, 1970, these odd, little postcard-sized objects, three steel ball bearings suspended in plexiglass in a shadowboxed photo of a staircase.

Kugelobjekt I, 1970, image: gerhard-richter.com

And anyway, on the next page, Richter explains how all the work on the dimensions and framing and installation of 4 Panes of Glass meant it’s “not a readymade, any more than Duchamp’s Large Glass is,” when he goes,

At one point I nearly bought a readymade. It was a motor-driven clown doll, about 1.5 metres tall, which stood up and then collapsed into itself. It cost over 600 DM at that time, and I couldn’t afford it. Sometimes I regret not having bought that clown.

You would have exhibited it just like that, as an uncorrected readymade?

Just like that. There are just a few rare cases when one regrets not having done a thing, and that’s one of them. Otherwise, I would have forgotten it long ago.

And I’m like, the clown! the clown! I swear, I’d written about it before, but I can’t find it anywhere. And then I realize I’d written about it for the NY Times in 2005.

Previous most ridiculous sculptures I could imagine: The International Prototype Kilogram or Le Grand K, and the Avogadro Project

UPDATE:, uh, no. Richter has more balls than I thought.

Any Ignoramus In The Universe

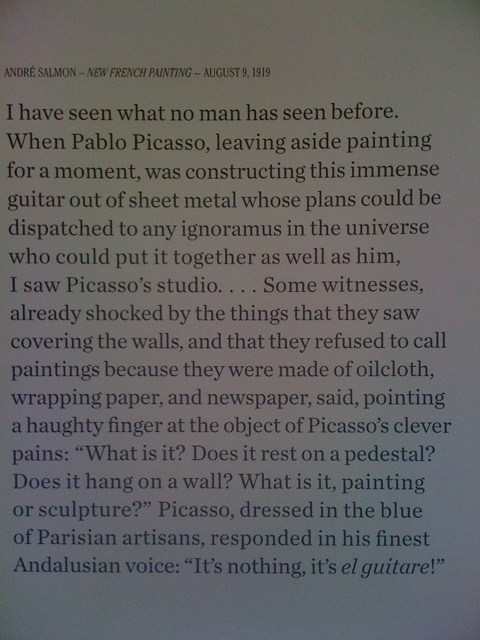

Wall Text from MoMA’s Picasso Guitars show, via @bryanthepainter

I’ve been loving Bryan’s tweets of the various pullquotes in MoMA’s incredible Picasso Guitars show, but none more than this one from Andre Salmon in 1919, where Picasso apparently invented and ignored the kind of instruction-based art that Moholy Nagy’s Telephone Paintings–and Judd’s outsourced fabrications–would later become famous for.

Here’s the full quote:

I have seen what no man has seen before. When Pablo Picasso, leaving aside painting for a moment, was constructing this immense guitar out of sheet metal whose plans could be dispatched to any ignoramus in the universe who could put it together as well as him, I saw PIcasso’s studio. [It was] more chimerical than Faust’s laboratory. This studio, which certain people may claim contained no work of art in the old sense, was furnished with the newest of objects. All the discernible forms surrounding me appeared absolutely new. I had never seen such new things before. [Before that] I did not know what a new subject could be.

Picasso Guitars: 1912-1914 opens this weekend at MoMA [moma.org]

Related: “Idiots can do what I do.” – Gerhard Richter

[2022 update: non-functioning twitter links removed, link to MoMA show archive added.]

Mientras Tanto En Mexico,

While poking around online about Tate Modern’s version of the Gabriel Orozco retrospective, I found this rather incredible letter from 2009, written, apparently by Orozco himself, to his dealer Jose Kuri. The letter is an ostensibily-but-not-really private round in an ongoing, public, critical battle for some kind of primacy within the Mexican art world.

Orozco defends and praises his own success and innovation–to his own dealer–while slamming both other artists [cough, Santiago Sierra, Francis Alys] and their critic/curatorial champions [Cuauhtémoc Medina, who I will be adding to the greg.org art pronunciation list shortly.]

Anyway, this kind of veiled subtexts with an apparent academic impartiality and a deficient documentation, derive from a cheap historicism, where the talent of the individual to understand his/her moment, and to do the things that he feels like it and with it finding new art for life and for the work, will never be the reason for his success. If anything, it can seem incredible to those Mexicans, that a co-national has innovated and influenced other artists in the world, which, although is not mentioned -in the breakdown of the ingredients for my success-, is a measure and perhaps the main reason for the success of my work in this years. Novelty, not exoticism, is what makes fortune. And the one that makes something before the others becomes an essential reference point. Success came after the creation of something new… which was successful.

Wow, OK. I have been a diehard fan of Orozco’s work for almost 20 years now; I still see him as having a formative influence on my eye, and on the whole way I see the world in relation to art. Or to his art. And maybe I just don’t/can’t appreciate the nationalist/politicized context in which this debate is occurring.

But I’m trying to come up with examples of other artists who aren’t Julian Schnabel who take such on the record personal affront. I guess Rob Storr loves to deal out the smackdowns, too. Anyway, the Centre For The Aesthetic Revolution has the whole thing. Definitely check it out.

GABRIEL OROZCO ‘THE SECRET OF HIS MIRACULOUS SUCCESS’ A LETTER TO HIS GALLERIST IN DEFENSE OF SOME OF HIS CRITICS [centrefortheaestheticrevolution]

Also from the Centre For The Aesthetic Revolution, word that the Hotel Palenque has finished the renovations, and is open for business. This apparently happened some time between Robert Smithson’s drunken slide lecture about it in 1972 and the arrival of the Google Street View coche.

My Google Art Project, Part 1A

Here’s the introductory text I wrote last Spring for Walking Man – A Collaborative Self-Portrait With Google Street View. I made some proofs, but I’m still figuring out the best size. If I do decide to publish it, I may polish up the title a bit.

And I’ll probably revise it. Street View’s imagery and technique seems to me to turn a lot of critical thinking about photography on its head, but as much as the theoretical implications fascinate me, every time I start writing about them, I feel like a poseur.

As ongoing enhancements and even promotional stunts like Google Art Project affirm, Google executives are working to make Street View the primary tool for us “visual animals,” a browser for the physical world. Robert Smithson wrote about studying massive infrastructures like dams to discover “unexpected aesthetic information.” Google is creating the most massive visual infrastructure project right now, and it is chock full of unexpected visual information.

Happy Birthday, Gertrude Stein

May your wife have a cow every time.

‘The Excess of Unimportant Information’

Though to a guy making something called Atlas in his spare time it still probably feels pretty empty and limited, Gerhard Richter’s website is pretty expansive. Via Twitter, we learn that his web elves have just added a quotes section, most of which is taken from Gerhard Richter: Text. Writing, Interviews and Letters 1961-2007 (2009), the UK edition of the artist’s second collection of writings, both of which were edited by Hans Ulrich Obrist.

I was about to bit the bullet and buy the expensive, out-of-print The Daily Practice of Painting: Writings 1962-1993 when the new edition came out, and I’ve hesitated, waiting to see how or if the two volumes overlap. So far, I’ve seen nothing; I guess I’ll have to pigeonhole Hans-Ulrich at the next global 24-hr art lecture marathon.

Meanwhile, I went ahead and bought Gerhard Richter: Writings 1961 – 2007, the US edition, so I’m just a couple of days away from seeing whether this awesome quote about blurring from 1964-5 [!] is, in fact, on page 33:

I blur things to make everything equally important and equally unimportant. I blur things so that they do not look artistic or craftsmanlike but technological, smooth and perfect. I blur things to make all the parts a closer fit. Perhaps I also blur out the excess of unimportant information.

Having A Cow

After dropping in on the National Portrait Gallery’s daylong symposium [it’s still going on, in fact] connected to Hide/Seek just now, and though I only saw two presentations, whoa–I feel like a cigarette.

Jonathan Katz, co-curator of Hide/Seek, titled his paper: The Sexuality of Abstraction: Agnes Martin, and he rather amazingly addressed Martin’s embrace of the substantive stasis of Zen as an alternative to the more prevalent and problematic model of the closet for not addressing her lesbianism. Which she at once did and did not do in some of her formative early New York work, and which she very much did not do when she wrote and talked so extensively about her work.

One particular work, a 1961 drawing titled Cow, for example, has been traced to an illustration in her D.T. Suzuki book, where an oxherder and an ox contemplate a circle in a square. And then Katz read a quote from the artist’s statements from one of Martin first shows in NYC, in which she quoted a famously, directly erotic Gertrude Stein poem–but stopped right before the hot parts. And–who knew? not I–he read some other famous-among-lesbians poem where Stein rather rhythmically builds up, and up, and up, to the moment of climax–which is symbolized by a cow. Suffice it to say, Katz’s phrase, “Stein’s orgasmic cows” is now right next to Gorky’s “cosmic vulva” in the modernist discourse. [Holy smokes, I just Googled “cosmic vulva” and Gorky and came up empty. Have I not told that story? My apologies. Let me rest up, and then I’ll get right back into it. I’m not 19 anymore, you know.]

Anyway, hot on the heels of Martin’s Zen sex koans, Dominic Johnson presented work from his forthcoming book on Jack Smith’s 1963 film Flaming Creatures and what he calls the “burden of disgust.”

I’d heard the general story of the obscenity controversy around Flaming Creatures, prints of which were seized by police, and became the basis for several criminal obscenity cases and appeals. But I had no idea that when Lyndon Johnson was nominating Abe Fortas to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1968, conservative senators, led by Strom Thurmond, raised Fortas’s criticism of the Flaming Creatures convictions as evidence of liberalism’s inherent perversity.

And that to make his point–are you sitting down? You really should be sitting down–Thurmond organized a Senate screening of Flaming Creatures during the Fortas hearings. And he sandwiched Smith’s avant-garde piece between a random strip-tease film, and a couple of run-of-the-mill straight hardcore porn flicks. At the Senate. Charles Keating apparently told Newsweek that the film was so disgusting, it didn’t even arouse him. This he told to Newsweek.

Sometimes it feels like you think you know the world you’re living in, and sometimes, wow, you just don’t.

WOW, HAS IT BEEN TWO YEARS? UPDATE I was searching to see about Johnson’s Jack Smith book, and I found the videos of the “Hide/Seek” symposium presentations, so I added them here. Good times.

Meanwhile, the book, Glorious Catastrophe: Jack Smith, performance and visual culture, was released last summer. I haven’t seen it, or any reviews of it, which seems unusual.

An Avalanche Of Awesome

I’ve been kind of busy, and I didn’t want to get fingerprints all over the signed edition, and my few original issues are in storage somewhere, so I’m really only now getting a look at Primary Information’s beautiful facsimile copy of Avalanche magazine. I’m on page nine and I’m tempted to blog my way through the whole thing. Just so much going on. Here’s a taste from Avalanche No. 1, Fall 1970, from Rumbles, the front-of-the-book, which reads like the alumni news section of Conceptual Art University:

James Turrell, 27-year-old LA sculptor, who has not formally exhibited since his only one-man show of projected light works organized by John Coplans at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967…In April 1969, Turrell and Sam Francis made a sky drawing using two World War I biplanes, radio-controlled from the ground, as part of Easter Sunday in Brookside Park organized by Oliver Andrews, Judy Gerowitz [!] and Lloyd Hamrol, who participated with elemental outdoor projects…

…

Work began this summer on Paolo Soleri’s Arosanti, a rural housing complex for two thousand inhabitants on a seven acre site seventy miles north of Phoenix, Arizona…

…

The Museum of Conceptual Art opened on Wednesday, March 18 in San Francisco’s Market Street district with a participatino piece in which buckets of paint were given to the guests to paint the walls white….MOCA’s latest show, Sound Sculpture As a one night presentation of successive sound events by ten Bay Area artists, was held on April 30…Allan Fish‘s piece was performed by Tom Marioni. Perched atop an eight foot ladder, he pissed into a galvanized washtub. As the tub filled, the sound dropped in pitch. He was followed by Terry Fox, who scraped a shovel across the linoleum floor and vibrated a thin plexiglas sheet very fast. Jim McCready paraded four girls wearing shiny nylons down a 3×9′ long rug. As they rubbed their thighs together a swishing sound was heard….

…

Andy Warhol…now has financial backing for his first Hollywood-based film, Specimen Days, the story of Walt Whitman’s experiences as a Civil War male nurse. With shooting set to begin around mid-October in New Orleans, the regulars are ready but the lead is still to be cast. Allen Ginsberg, Mick Jagger, and John Lennon have all turned it down.

…

After his recent New York visit, LA based artist Terry O’Shea has returned to California and plans to execute a large-scale ecological project involving fast-growing plants.

…

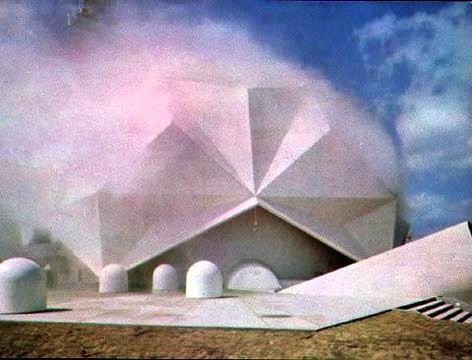

The Japanese police detained San Francisco artist Paul Cotton for wearing a pink bunny costume to the Pepsi Pavilion at Osaka’s World’s Fair. John Perreault gave Marjorie Strider his old Iowa summer teaching job so that he could concentrate on his first book for Abrams, Andy Warhol

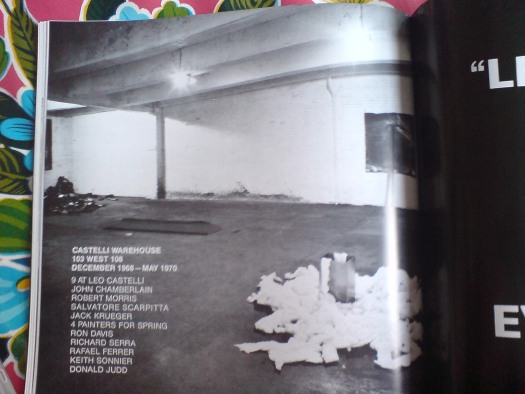

Ooh, an ad for 9 at Leo Castelli, the seminal show Robert Morris curated at Castelli Warehouse–which was not the Castelli Warehouse from which Jasper Johns’ Short Circuit flag painting was taken, but still.

Ooh, a big picture of the misty Pepsi Pavilion surrounded by moving sculptures in the ad for Robert Breer’s show at Galeria Bonino? Where is Robert Breer these days, btw? That’s not a rhetorical question, either.

The trade edition of Avalanche is under $100 at Amazon. The first nine pages, at least, are highly recommended.

Art In Process: Reading Finch College Museum

Now we’re getting somewhere, even if it’s only to the library.

Since the Finch College Museum was originally [and wrongly] fingered as the site of the theft of Johns’ Flag from Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit, I’ve been looking for months to buy a copy of the 1967 exhibition catalogue for Art In Process: The Visual Development of a Collage. Well, not so easy. Increasingly desperate and frustrated with the failings of the Internet Age, I decided check the library. Turns out the Smithsonian’s Museum of American Art library, right next door to the Archive of American Art, had a copy. Took like two minutes.

Art In Process was a series of topical, process-oriented, teaching exhibitions organized by Finch College Museum director Elayne Varian. They included sketches, models and studies to show how the artist did what he was doing. From Finch, which was on East 75th Street, the show traveled for 18 months to nine other smaller museums around the country in a tour organized by the American Federation of Arts. [Thanks to the original press release, provided by the AFA, the list of venues is below.]

I’m not the only one who had trouble finding the catalogue, though. Paul Schimmel’s huge Rauschenberg Combines catalogue said the flag painting was stolen while Short Circuit was on exhibit. That’s how he read the entry in Walter Hopps’ 1976 retrospective catalogue, which mentioned Finch and the missing flag together.

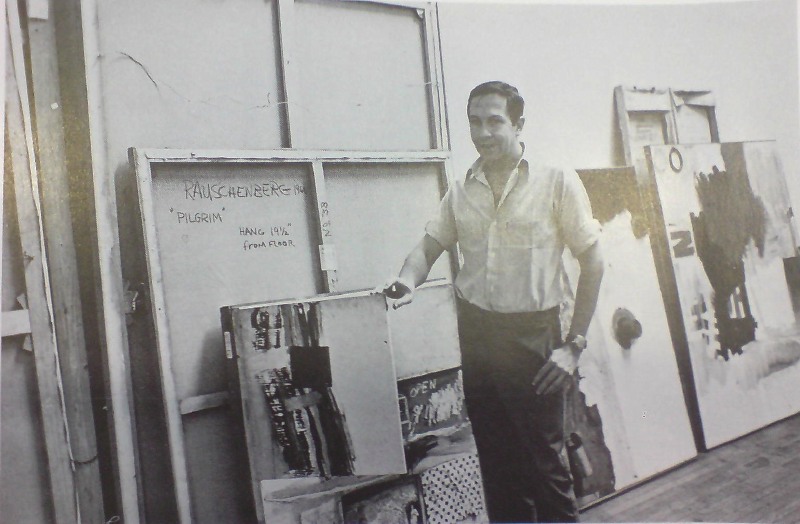

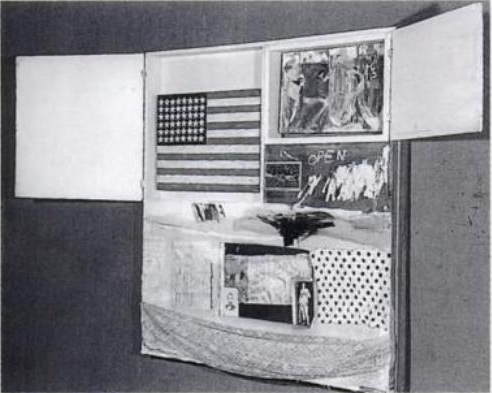

But. Check out what Rauschenberg actually said. Well first, check out that photo!

It’s Bob, teasing us with what’s behind Short Circuit Door No. 1. Because there is nothing:

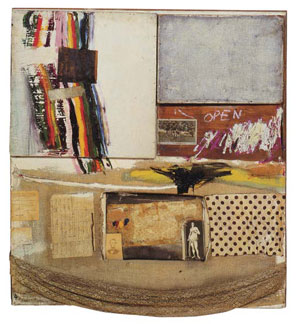

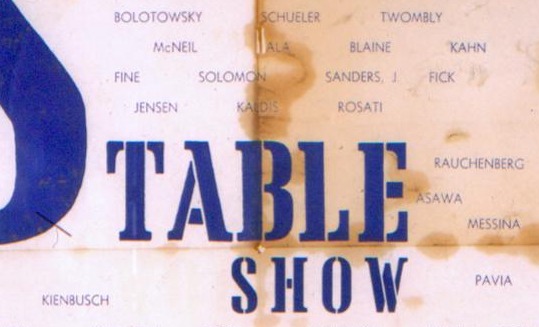

In the third Artist Show at the Stable Gallery, my collage, SHORT CIRCUIT, 1955, was motivated by the protest that there had not been any new artists invited to exhibit. Therefore, I invited four artists: Jasper Johns, Stan Vanderbeek, Sue Weil and Ray Johnson to give me works to be built into my collage. Only two paintings were ready in time to be installed into the major piece. The collage also contains the autograph of Judy Garland, and one of the first programs of a John Cage concert. Because Jasper Johns’ flag for the collage was stolen, Elaine Sturtevant is painting an original flag in the manner of Jasper Johns’ to replace it. This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.

Give me. Built into. My collage. Only two. Is painting. These are the phrases that jump out at me.

Not only was Art In Process the first acknowledgment of the removal of Johns’ flag, almost two years after it happened, it was the first public exhibition for Short Circuit since Alan Solomon’s group show at Cornell in 1958. After being the subject of some kind of joint, post-breakup negation agreement between Johns and Rauschenberg, where the combine was not exhibited, published, or even, it seems, discussed, Short Circuit went on a cross-country tour, without the flag, and with the doors nailed shut.

I thought I’d be all Errol Morris about it and date the photograph from the other works in the background, but it doesn’t really help: Pilgrim (1960), on the left without its chair; Johanson’s Painting (1961), in the middle, with the tin cans, was in Ileana Sonnabend’s collection; the other combine painting with the N or Z element, I haven’t found yet. [Any ideas? Send’em in!] That watch Bob’s wearing looks like the one in the Avedon photo on the cover of Schimmel’s Combines, which was taken in 1960. But I’ll say Bob’s face looks a few years older, at least five, if not seven.

So this photo was probably not, then, taken before 1965. And Johns’ flag painting is probably not, then, behind that door. And Bob is probably not, then, toying with the terms of the no-repro “solution” he and Johns devised for this double document.

Other things: Sturtevant’s flag sounds like it’s in process. Unless that “Sturtevant is painting an original flag” is the same tense as “I am making an animated musical,” somewhere well short of “she’s delivering it this week,” and closer to “well, we’ve talked about it.” Because though a Sturtevant flag sighting was reported in 1971, There were no photos of Short Circuit for Hopps to publish in 1976, and Rauschenberg talking of painting a flag himself because he “need(s) the therapy.” And when David Shapiro and Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe scouted the combine out in 1985, they had a “very sad experience” looking at the work, in a “state of real disrepair,” with mentions only of the absence of Johns’ flag and none of Sturtevant.

No mention of Ray Johnson’s inclusion. How classic for Johnson’s own collage that it gets subsumed so totally as Rauschenberg’s. It’s as if only the paintings can hold their own against the combine’s powers of assimilation. Resistance is futile. I guess that’s the real question here.

For Johnson, though, it’s probably the giddy answer. He was also included in Art in Process on his own, so don’t sweat for him. If anything, that’s how he wanted it. Here’s writer/artist/curator Sebastian Matthews:

Over the next decade, Johnson made a series of anti-rectangle collages. It wasn’t long before Johnson was mailing out collage fragments “for others to use or send on,” letting go authorship (at least in part) and allowing the work to be formed by increasingly random collaborations. No coincidence, then, that Johnson made this creative leap during his transition from Black Mountain to New York City while hanging out with his BMC buddies.

That’s from Matthews’ proposal/thesis for an awesome-sounding show, BMC to NYC: The Tutelary Years of Ray Johnson, which he organized last fall at Black Mountain College + Arts Center in Asheville, NC. Sounds like Short Circuit was as formative and in harmony with Johnson’s emerging practice as it was problematic for Johns’. That may be too simplistic, but it’s way past time to take a closer look at the rest of Short Circuit, too.

The dimensions: The Finch catalogue lists the dimensions for Short Circuit as 48 x 48 inches, which, since Bob was not seven feet tall in that picture, is obviously wrong.

Another reason for checking the Finch catalogue was to see whether Short Circuit was still owned by Rauschenberg or, if it was still, as Michael Crichton reported, in Leo Castelli’s collection. And it doesn’t say. But the press release might. Artists, like Al Hansen, were listed as lenders for some works in Art In Process, but works were credited to the artists’ dealers. Short Circuit was apparently lent not by Rauschenberg, but by Leo Castelli Gallery. The mounted photocopies of letters to Ray Johnson, Stan Vanderbeck [sic] and Susan Weil, meanwhile, were lent “anonymously.” Wait, the what?

Continue reading “Art In Process: Reading Finch College Museum”

Q For Institutionally Affiliated Readers Of greg.org: Res 10?

If you can see the full text of “On Collaboration In Art,” David Shapiro’s conversation with John Cage, published in the Autumn 1985 issue, (No. 10) of Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, perhaps you can tell me if it does, in fact, discuss Rauschenberg and Johns’ work on Short Circuit as the web-based search appears to indicate?

Thanks!

On Collaboration in Art: A Conversation with David Shapiro

David Shapiro and John Cage

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics

No. 10 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 103-116 [jstor.org]

update: Thanks to greg.org readers B and G, we know the answer is yes, yes it does, and wow, very interesting. Here is Shapiro asking his friend Cage about Black Mountain and how he perceives collaboration:

DS: So collaboration also implied simultaneity?

JC: That’s all it really means to me.

DS: Two things happening at the same time.

JC: That is their relationship.

DS: Bob Rauschenberg often seems optimistic, inclusive, as if he’s marrying the whole world, like permitting Jasper Johns’s flag to be inside a larger sculpture. It seems like a sign of generosity. He sometimes seems generous in his collaborative spirit. You don’t think of it as necessarily emotionally generous to collaborate? Is it not a sign of charity?

JC: No. It’s a willingness to have your work experienced at the same time other work is experienced. I’m being careful not to use the expression “willingness to come together,” because there’s no coming together really. It’s two different different things that if they do come together at all, they come together where Marcel [Duchamp] said a work of art was completed, in the observer. But the two people who are collaborating are not observers until they can be. Then, when they are observers, they’re no longer collaborators.

I was going to add italics for the rather salient language these folks were using, but well, where to stop?

Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe was there, too, and Shapiro’s wife, the architect Lindsay Stamm Shapiro. McCabe really wanted Short Circuit for the Hirshhorn’s 1985 exhibition, “Artistic Collaboration in the Twentieth Century”:

CM: We just had a very sad experience looking at the Rauschenberg Short Circuit that Jasper had done with him and Susan Weill [sic]. It’s now in a state of real disrepair. It’s so important for this exhibition.

LS: Where is it?

DS: It’s in Rauschenberg’s studio, but Johns’s flag had been stolen at the place. It had been shown at Finch College. It is like a wing to an altarpiece, and inside was a Susan Weill. I’m sure you’ve seen it.

CM: There was a little sticker in there, I’m trying to think of which was the work, it says “Cage.”

DS: Yes, it has a little collage mentioning a performance that you had done. I think with David Tudor. When David Tudor does chord clusters in the record indeterminacies, was that collaborative or completely mapped out by you, so he’s the performer?

JC: He’s playing the Solo for Piano from the Concert for Piano and Orchestra.

From Solomon’s ‘The New Art’

A little Saturday stenography. Alan Solomon wrote “The New Art,” a catalogue essay for “The Popular Image,” one of the first museum exhibitions of Pop Art, organized by Alice Denney in the spring of 1963 at the fledgling Washington Gallery of Modern Art. [Solomon would go on to restage the show in the ICA in London that fall, sort of obscuring or usurping Denney’s and the WGMA’s position in the history of Pop.]

Anyway, Solomon, who had just left Cornell to establish the Jewish Museum’s contemporary program, where he gave Rauschenberg his first retrospective, and who would soon be the commissioner at the Venice Biennale where Rauschenberg would be the first American to win the International Painting Prize, discussed both Rauschenberg and Johns, along with Allan Kaprow, as key influences on the nascent Pop Artists. Because no one else seems to have put it online, here are some extended excerpts from Solomon’s essay:

The point of view of the new artists depends on two basic ideas which were transmitted to them by a pair of older (in a stylistic sense) members of the group, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. A statement by Rauschenberg which has by now become quite familiar implicitly contains the first of these ideas:

Painting relates to both art and life. Neither can be made. (I try to act in the gap between the two.)

Rauschenberg, along with the sculptor Richard Stankiewicz, was one of the first artists of this generation to take up again ideas which had originated fifty yeras earlier int he objects made or “found” by Picasso, Duchamp, and various members of the Dada group. Raschenberg’s statement, however, suggests a much more acute consciousness of the possibility of breaking down the distinction between the artist and his life on the one hand, and the thing made on the other.

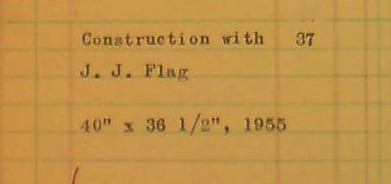

‘Construction With J.J. Flag’

tiny detail of a Robert Rauschenberg registry, dated 1957-9, which I can’t reproduce in full because of the terms of access to the Leo Castelli Gallery Archive at the Archives of American Art

Another day back in the Leo Castelli Gallery papers at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art, and barely further along in my project to piece together the surprisingly complex history of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit.

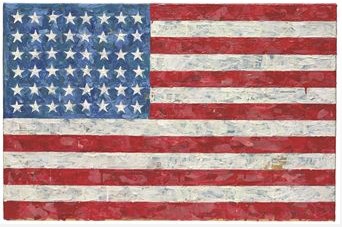

After finding Castelli’s insurance claim for the “loss” of the Jasper Johns flag painting which was originally included in Short Circuit–a claim which makes absolutely no mention of Short Circuit itself or Rauschenberg–and reading Michael Crichton’s first published account of what happened, I wanted to see if there was any record of Short Circuit entering Castelli’s collection.

There was not.

The folks at the AAA who’d processed Castelli’s archive had already warned me that there was remarkably little personal material, and little relating to Castelli’s own collection. Nevertheless, there were plenty of traces of Leo’s own holdings scattered throughout the files; when Rauschenberg’s Bed was discussed, for example, Castelli’s ownership of it was at least mentioned.

What I came to see, though, is that especially when compared with other combine paintings from the 1950s, or, other works in Castelli’s and Rauschenberg’s collections, Short Circuit was almost completely absent from the ever-increasing stream of notes, discussion, and paperwork related to the artist’s career.

It’d be weird to lay out all the places that Short Circuit wasn’t, but I’ll give two examples: until the 1965 insurance claim, it never showed up in the photo reproduction orders the gallery sent to Rudy Burckhardt, who apparently shot all Rauschenberg’s [and other Castelli artists’] work at the time. In early 1967, when the gallery was negotiating with the British writer Andrew Forge to publish Rauschenberg’s first monograph, Short Circuit was not included in any otherwise comprehensive-seeming works lists or photo lists he received.

I have to think this negation-by-withdrawal is linked to Rauschenberg’s breakup with Johns, and to what Johns referred to in 1962 as the “solution of differences of opinion between him and me over commercial and aesthetic values relating to that work.” So long as had Johns’ flag painting in it, Rauschenberg was to keep the work out of public circulation.

In fact, the only archive mention of Short Circuit at all before Rauschenberg’s 1976 Walter Hopps retrospective, is in an early artist’s registry. The looseleaf, ledger paper list is dated 1957-59, when Rauschenberg and Johns were together and both having groundbreaking first solo shows at Castelli [in 1958, Johns in January, and Rauschenberg in March].

And technically, it wasn’t even Short Circuit; it was listed as “Construction with J.J. Flag,” with the dimensions and date, “40 x 36 1/2, 1955.”

There’s alo a handwritten notation that the work had been exhibited at Cornell University in the spring of 1958. That would be the second showing Johns had referred to in 1962. [The first, the 1955 Stable Gallery show for which it was created, is not mentioned.] The idea that Short Circuit–a work which merged the two artists’ signature innovations–was exhibited immediately after their controversial, back-to-back, solo shows would seem like big news. But no. Paul Schimmel’s 2005 Combines catalogue only lists the “group exhibition” in a footnote, and I haven’t found any other reference to the show online. In 1958, the director of the Cornell Museum would have been the critic/professor Alan Solomon, who was tight with all those Poppy guys. [He’d go on to curate definitional Pop Art shows in 1962.] I’ve contacted Cornell; we’ll see if they have anything on the show.

If there was a “difference of opinion” about publicly displaying Short Circuit, I think we can assume that Johns did not want it shown, and Rauschenberg did. Because soon after the flag painting was removed, Rauschenberg put the combine into Elayne Varian’s traveling collage exhibition at Finch College Museum–with the doors nailed shut.

It’s funny, all this time I’ve been poking around this piece, I’ve thought of it in terms of “getting the Johns back.” But when you think about it, the one who got his work back in this caper is Rauschenberg.

UPDATE: Whoa, I just noticed that the dimension mentioned above–40 x 36 1/2″–don’t match up at all with those given in Hopps’s 1976 catalogue: 49 3/4 x 46 1/2. What up? Is “Construction with J.J. Flag” NOT Short Circuit after all? It is an error, another missing flag/combine combo, or an upending of the original Stable Gallery story? If the Johns flag is 17″ or so, there is no way that piece above is 50″, or even 46″. Gagosian lists the dimensions as 40 3/4 x 37 1/2″, which is close enough for me. No sweat, Hopps & co just had bad info.

‘Active Participation in the Life and Thought and Movement of Their Own Time’

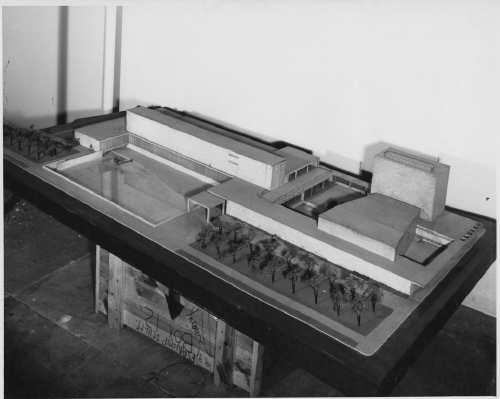

Huh, so I’m poking around online for info on the Saarinens’ unrealized design for a Smithsonian Gallery of Art [above is a SI photo of the model, built in 1939 by Ray and Charles Eames, of all people, perched atop, of all things, the crate for a Paul Manship sculpture. And I’m thinking how it’s too bad that WWII happened, because otherwise we’d have a sweet modernist art museum on the Mall–hah, as if.]

[According to the Smithsonian American Art Museum’s own history, the building never had a chance. It wasn’t Congressional budget cuts or wartime reprioritizations that killed the project–it was the rejection of the modernist design by the Smithsonian Regents themselves, and by the Commission on Fine Arts–because it was modernist.]

[Charles Moore, an influential retired Chairman of the CFA called its “sheer ugliness…an epitome of the chaos of the Nazi art of today.” Which, yow. The Commission which rejected it included sculptors Paul Manship and Mahonri Young, a grandson of Brigham Young.]

But that’s not the point. Point is, a quote stuck out from the book as being both timely and relevant. It’s from Holger Cahill, head of the WPA’s Federal Art Project [and holy smokes, Mr. Dorothy Miller], which organized artists to make work for public buildings and spaces. He believed art and artists and the public all benefit by “a sense of an active participation in the life and thought and movement of their own time.”

I haven’t found the original publication info, but since the source of that 1936 quote only appears on Google as a writing sample for an English 201 course, I put the whole thing after the jump. Take a read and try to imagine it as not a politicized, partisanized view of contemporary art:

Continue reading “‘Active Participation in the Life and Thought and Movement of Their Own Time’”

Like Some Michael Crichton Novel

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Maybe it’s the CSI-ification of everything, but as I dig through archives and piece together timelines, and interview people–oh, I haven’t really mentioned the interviews, have I?–while trying to track down the story of Robert Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit and its little, missing, Jasper Johns Flag, I sometimes feel like a character in a John Grisham novel.

Which is funny, because the greatest book I’ve found on Jasper Johns so far is by Michael Crichton. Seriously, with his 1977 book, Jasper Johns, created for the artist’s mid-career retrospective at the Whitney, Crichton defined the exhibition-catalogue-as-pageturner genre.

After my most recent visit to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art last week, I had a few minutes to spare, so I ducked into the Museum of American Art Library across the hall to flip through Crichton’s catalogue and to see if there was any mention of Short Circuit in the supposedly exhaustive catalogue for Anthony d’Offay’s 1996 show of Johns’ Flags. [There wasn’t, and though it had a couple of good ideas, David Sylvester’s essay was uncharacteristically uninteresting.]

Well, flipping through Crichton’s book was riveting. I could only read a few pages, but it felt like a mystery, a suspenseful, personal investigation into the artist, his thinking, his process, and his work. It was chock full of quotes from people who know and work with Johns, evidence of Crichtons’ conversations and interrogations. I wanted to read every one. And it was only the recurring image of my kid waiting, alone, on the curb outside her pre-school, wondering why her daddy had forgotten her, that forced me to stop. It’s an intense, infectious curiosity that I admit I haven’t really felt towards Johns’ work before.

In the course of this recent, somewhat intense look at Early Johns, I’ve been struck and sometimes a bit put off by the artist’s apparent/reported hermeticism, his opaqueness. Not that I want art spoon-fed to me, or served up like some all-I-can-consume Baselian buffet. But if Johns wants to be obscure, closed, personal, private–yeah, I’ll go with closeted–then fine. Far be it from me to pry. And far be it from me to take advantage of that reticence by projecting my own theories and interests and speculations on the artist and his work, as a great deal of critical writing about Johns seems to do.

But while he addresses and acknowledges Johns’ seemingly impenetrable work and persona, Crichton also quotes a close friend saying something like, no, “Jasper wants to be understood.” [I’ll look it up later when my copy of the catalogue arrives.]

the very flaggish, hinged In Memory of My Feelings – Frank O’Hara, 1961, Art Inst. of Chi., via NPG

And that, coupled with the remarks from the curators of “Hide/Seek” that it was the first time Johns has ever allowed his work to be seen in a queer context [that link it to Michael Maizels’ discussion of the show], makes me feel that this longer, closer look at this painting–these paintings–is not just alright, but right. And that Johns would agree.

Anyway, the point is, buy this book. No, no, the point is, Johns rewards close, intense looking, and Short Circuit, both in its original state and throughout its fraught, altered history, feels like a key touchpoint in the works, lives, and careers of these artists. And it turns out that no one has gotten its story totally straight yet, not even Michael Crichton.

There is a note in Crichton’s Johns story that begins:

As a curious historical incident, a Johns painting was seen at the Stable Gallery in 1956, as part o a Rauschenberg painting.

Actually it was 1955. But then there’s this bombshell:

Leo Castelli later acquired the Rauschenberg with the two doors. He kept the painting in his warehouse. One day he examined the painting and dsicovered that the Johns flag had been stolen.

Wait, what?? Castelli bought Short Circuit? So it was not, after all, in Rauschenberg’s personal collection his whole life after all. And I only find this out after I leave the Castelli Archive. I wasn’t even looking for this kind of stuff. While it explains what Short Circuit was doing in Castelli’s warehouse, it doesn’t explain when Bob sold it, or why Leo bought it. Or why or when Bob got it back.

The artist Charles Yoder told me last month that Short Circuit was in Bob’s collection–and had Sturtevant’s replacement Johns Flag when he went to work for Bob in 1971. [Though the first published mention of Sturtevant I can find is still the Smithsonian’s 1976 catalogue, which ended up using Rudy Burckhardt’s original, Johns-era photo.] I guess I’ll have to get back to the Archive and look for Castelli’s own collection records. And his correspondence with Bob. And then look for the 1967-8 Finch College Collage checklist and/or catalogue, to see who was listed as the owner of Short Circuit, which was, remember, still described as containing a Johns Flag behind its nailed-shut doors.]

So this means that sometime between–well, we really don’t know when it was, just sometime before June 6, 1965–Castelli bought Short Circuit. And found the Johns Flag missing. But Crichton’s not through. “Castelli recalls a final incident in the story,” he writes:

Years later, a dealer–we do not need to say who–came to me and said, “Someone has brought me this Johns painting and I don’t kno wit, and I wondered if you could tell me about it, the date and so on.” I knew immediately what it was; it was the stolen painting. I said, “The painting has been stolen and I would like to keep it right here. I don’t want it to leave my gallery.” But this person said he had promised the person he got it from, and he didn’t feel he could leave it with me, and he said he would have to talk to the other person, and he was very insistent. So I said, “Well, all right.” I never saw the painting again.

“Castelli recalls”! “We do not need to say who”!

Well, this saves me a trip into Calvin Tomkins’ archives at MoMA; because I will bet that Crichton’s footnote is the source for the secondhand version of this incident Tomkins included his 1983 Rauschenberg bio. And where Tomkins ended broadly–and obviously wrongly–with “and nobody has seen it since,” Crichton nails the quote from Castelli: “I never saw the painting again.”

Which puts us back to where this whole thing started. Except that I think I now know–because I have been told by people who would know–who that dealer was, and who he was presenting the painting for. And based on some interviews I’ve done since, I am pretty sure I’m right.

But that turns out not to be the same as figuring out when the Johns Flag went missing, or more importantly, where it went, and where it is now. And even when Crichton quotes Castelli himself as calling the painting “stolen,” and I’ve seen it mentioned [albeit as “lost”] in an insurance report, when Castelli had the painting back in his gallery–and had chance to get it back from someone he obviously knows–he let it walk out the door again.

Michael Crichton died unexpectedly in 2008 while undergoing treatment for throat cancer. His art collection, including the Flag painting he bought directly from his friend Jasper Johns, which he considered his single most important acquisition, was auctioned last Spring at Christie’s. Mike Ovitz waxes a little hagiographic, and I deeply don’t get the Mark Tansey thing, but the video that Christie’s produced about Crichton and his passionate, intellectual engagement with art is really pretty good.

Measuring 17.5 x 26.75 inches, Crichton’s Johns Flag [above] is much smaller than the Flag which Castelli first saw in 1958 in Johns’ studio, an experience he later called, “Probably the crucial event in my career as an art dealer, and… an even more crucial one for art history.” It was slightly larger, though, than the Flag in Short Circuit [13.25 x 17.25 in.]. And it was painted between 1960-66, exactly the time when Short Circuit‘s Flag was being contested and lost–and shortly before Castelli got it back, and let it walk back out of his door. Crichton’s Flag sold in May 2010 for $28.6 million.