Congratulations to Spice DAO, which announced yesterday [sic] that they had successfully purchased a rare copy of a book containing the concept art and storyboard sketches for Alexander Jodorowsky’s legendary adaptation of Dune. The sale took place at Christie’s Paris on 21 November 2021, three days after Constitution DAO failed in its attempt to buy a printed copy of the US Constitution at Sotheby’s in New York.

Constitution DAO raised $47 million, only to be outbid by hedgie/collector Ken Griffin, whose privately negotiated guaranteed bid of basically $47 million and one dollars also included a rebate on the auction house’s premium, bringing his net to just $43 million. Spice DAO, no doubt quick learners, went into their auction for the EUR25,000 book with a EUR2.667 million bid, and managed to eke out a win.

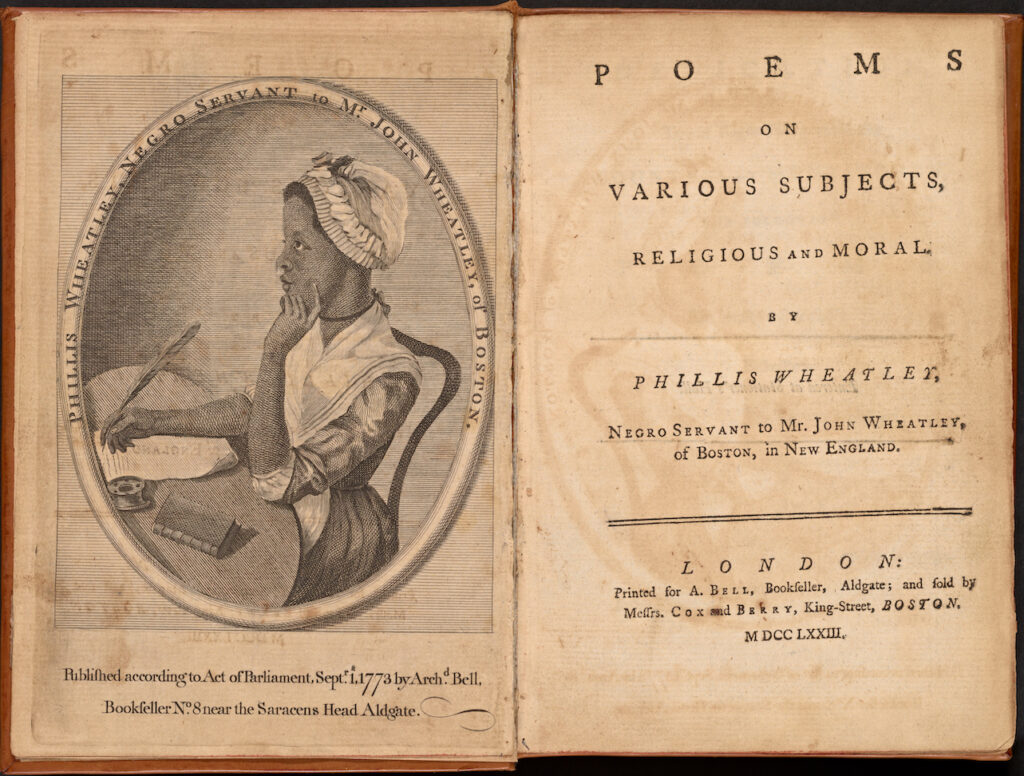

Spice DAO’s purchase–technically, a private purchase and a transfer to the DAO, since Christie’s didn’t recognize the DAO–of Jodorowsky’s Dune bible was actually revealed last December, when it was still called Dune DAO. The story then was that these enthusiastic Dune fans were banding together to liberate the long-hidden copy of the lost, unmade masterpiece they’d gotten glimpses of in Jodorowsky’s Dune, a 2013 documentary directed by Frank Pavich. It was only when they tweeted their plans to,

“1. Make the book public (to the extent permitted by law)

2. Produce an original animated limited series inspired by the book and sell it to a streaming service

3. Support derivative projects from the community”

that copyrightlulz twitter was like, “lmfao YEAH NO,” and the buyers of $11 million worth of Spice DAO tokens became aware of the limits of the blockchain’s ability to overcome all humanity’s problems.

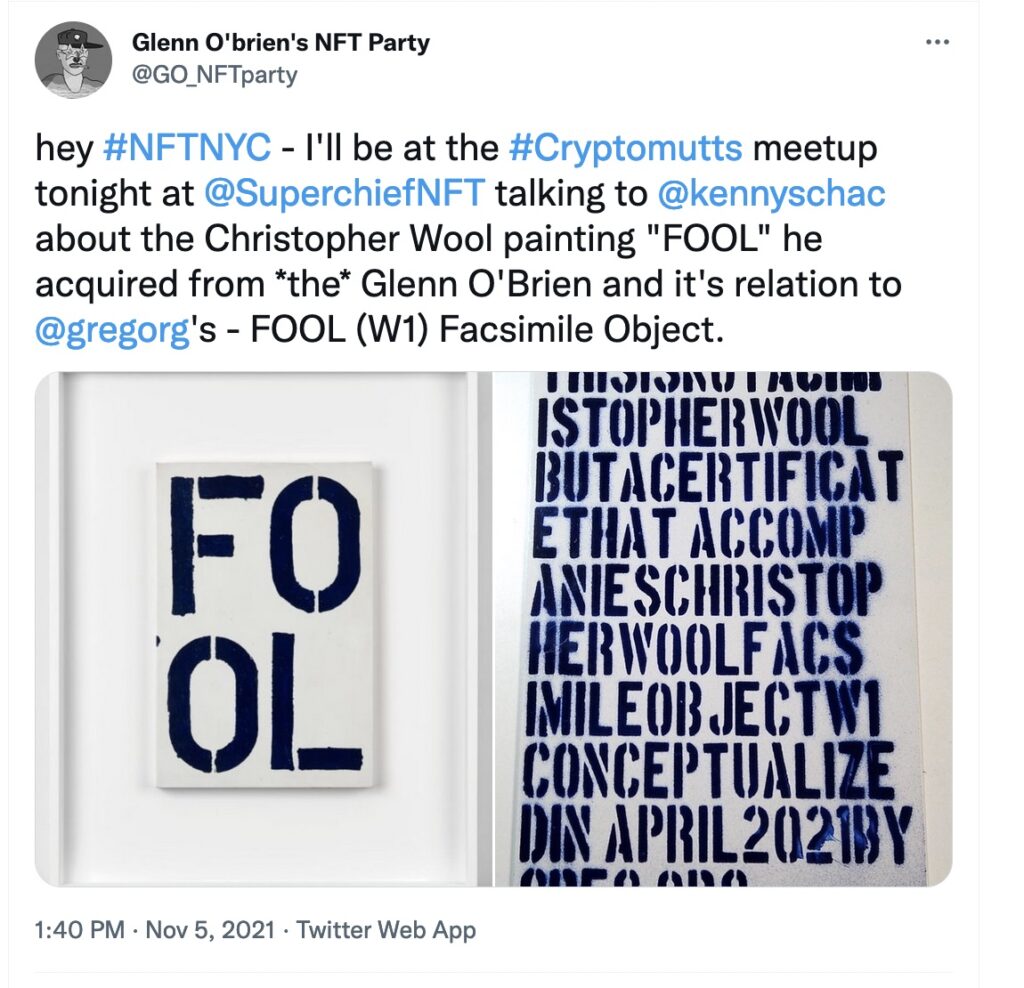

So while the governance discord debates selling NFTs of scans of the pages of Copy Number 5, then burning the actual book so they won’t get sued for copyright infringement [0.<], I am ready to move forward with the Spice DAO Facsimile Object (S1).

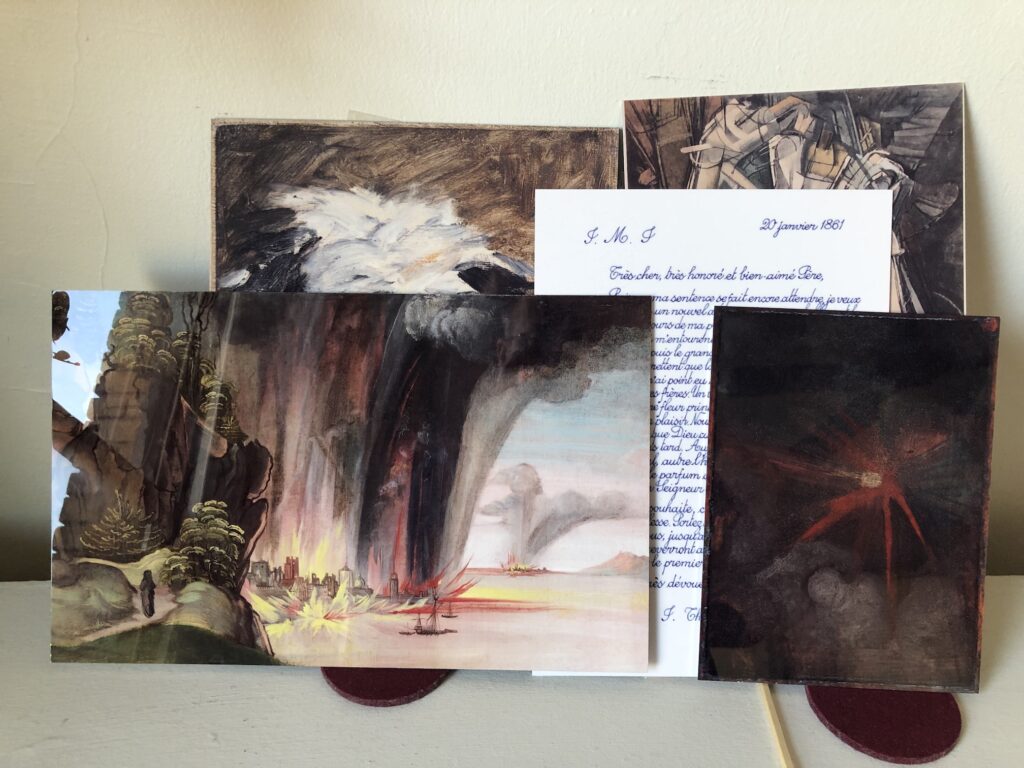

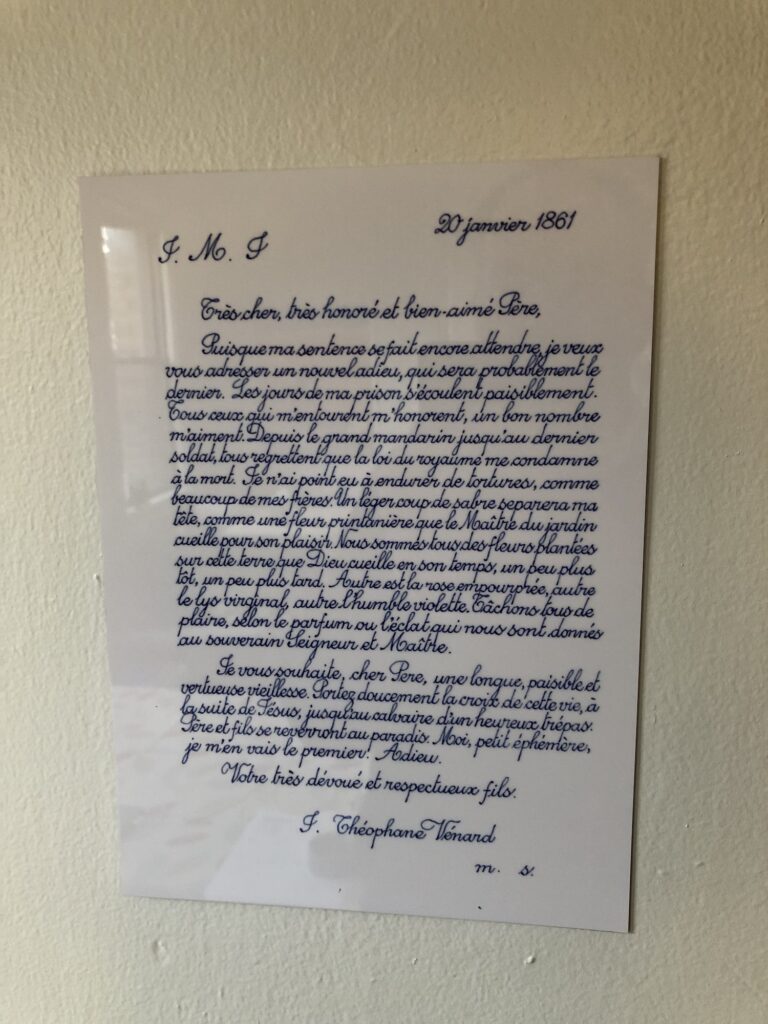

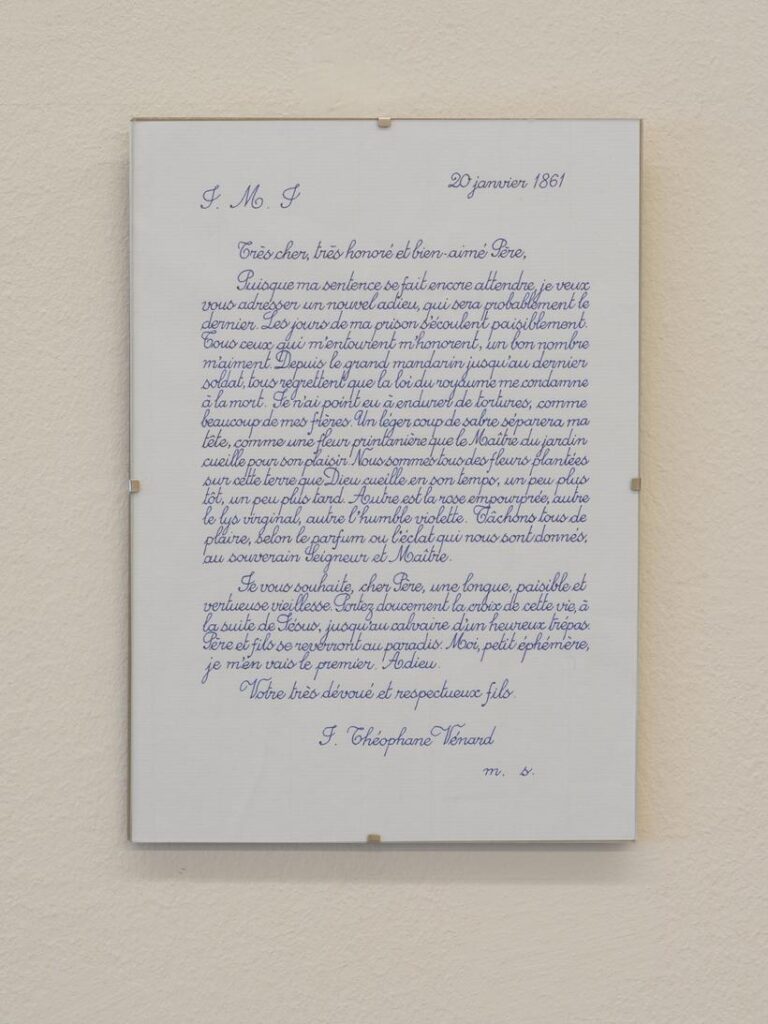

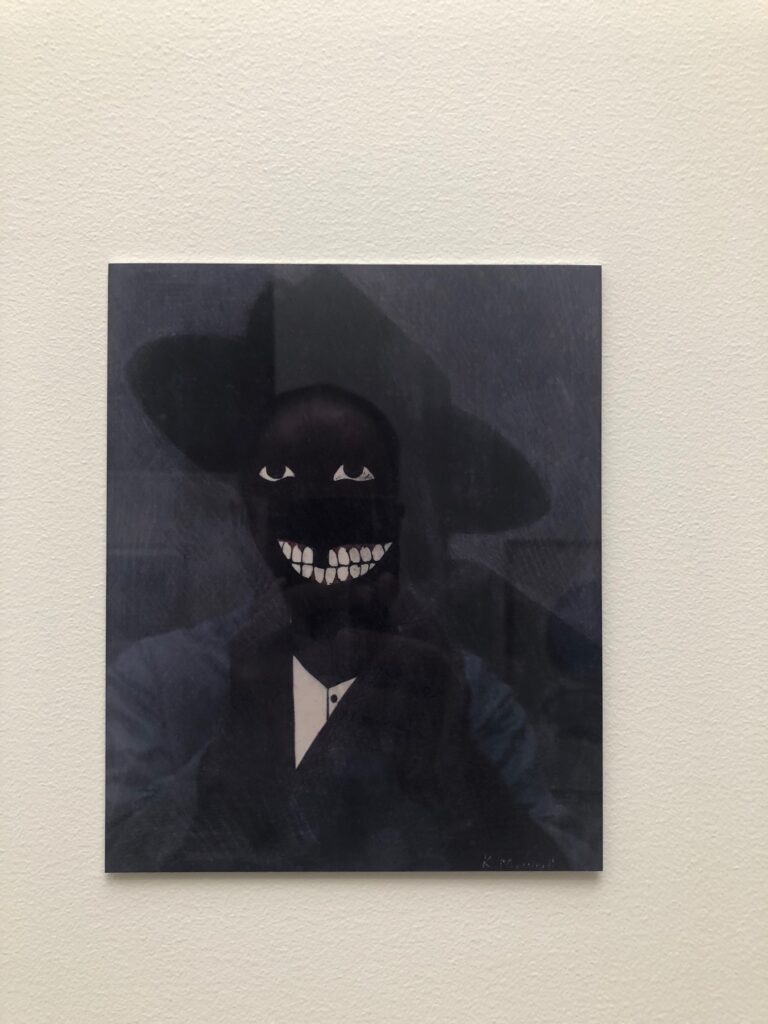

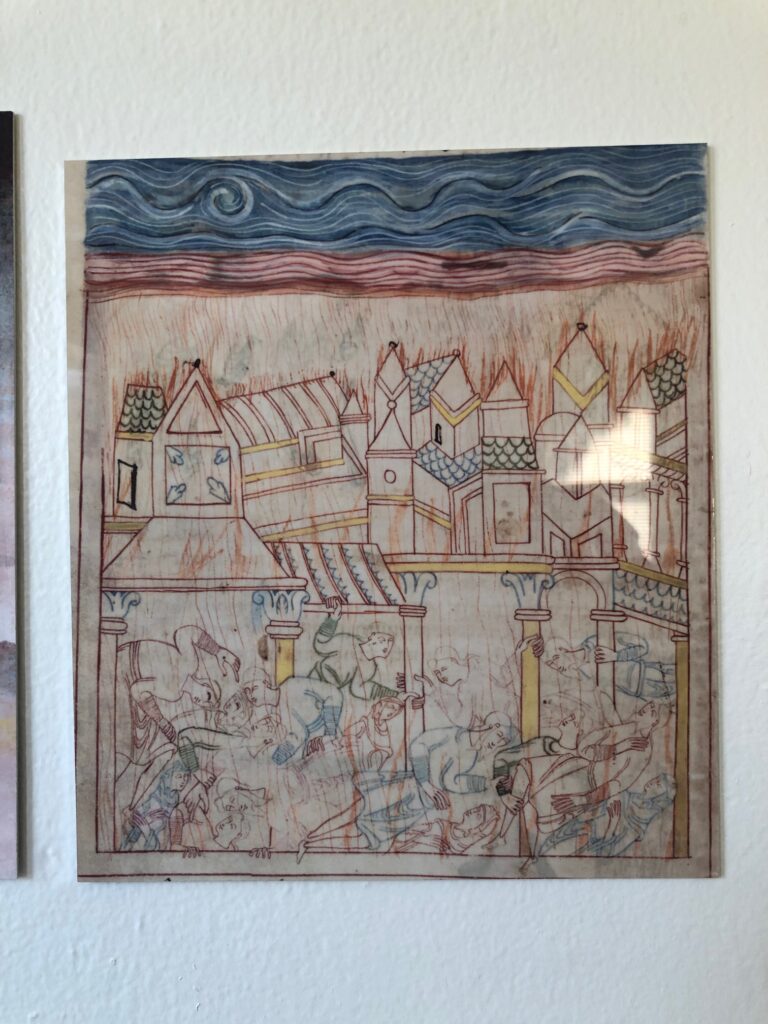

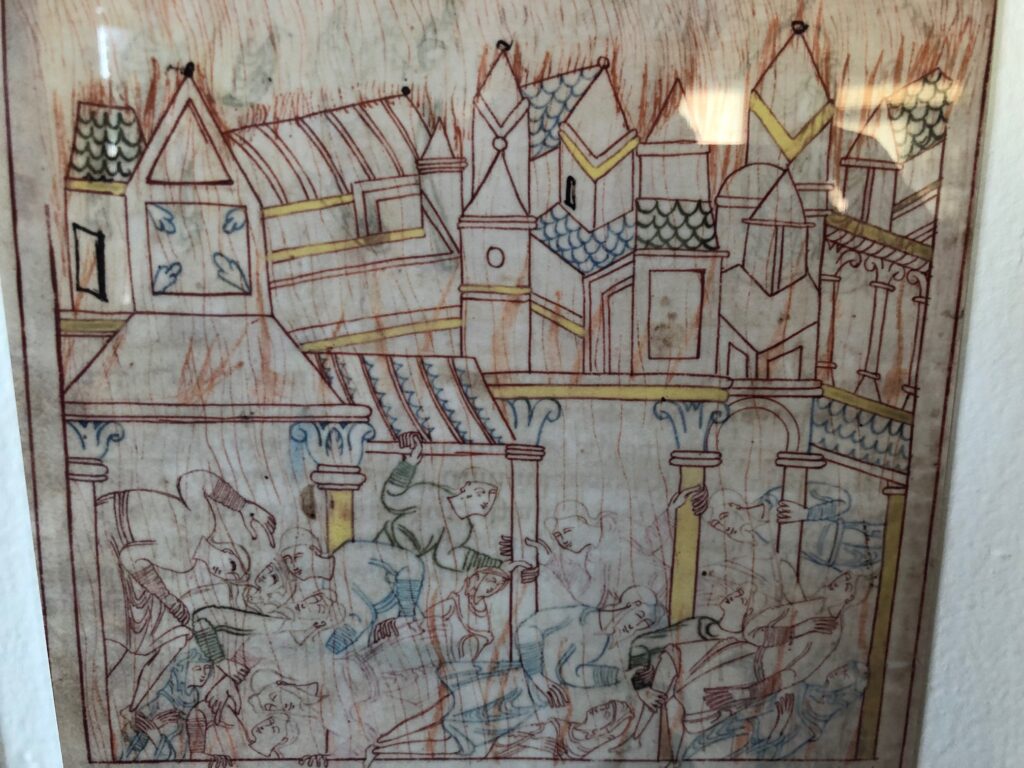

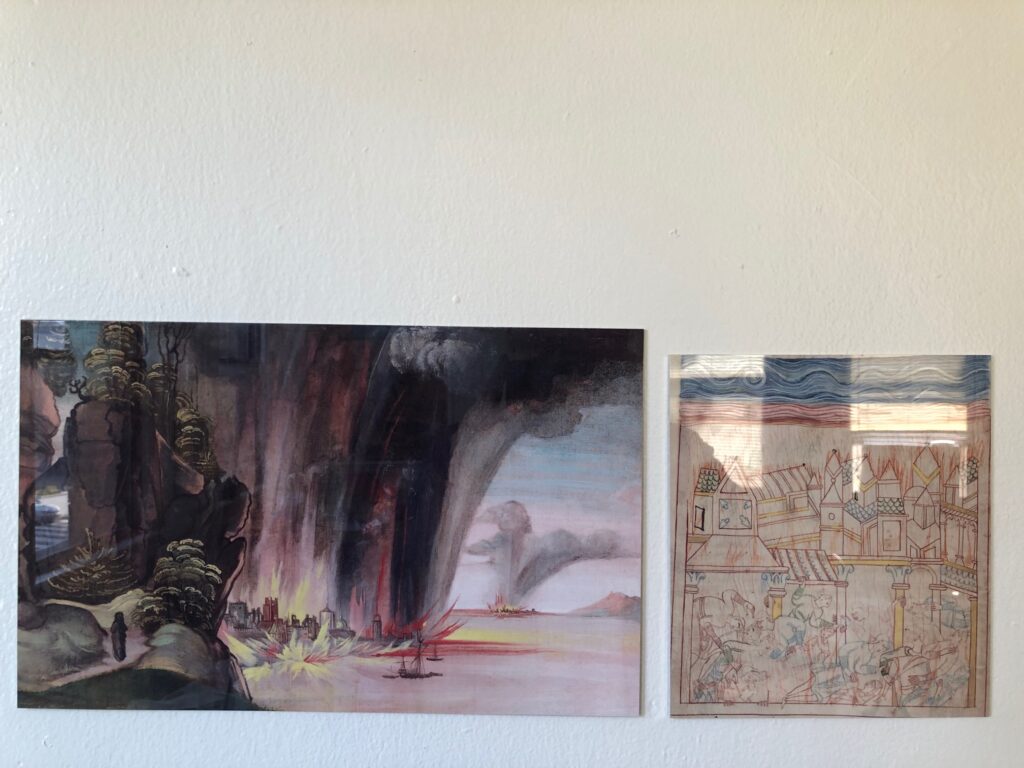

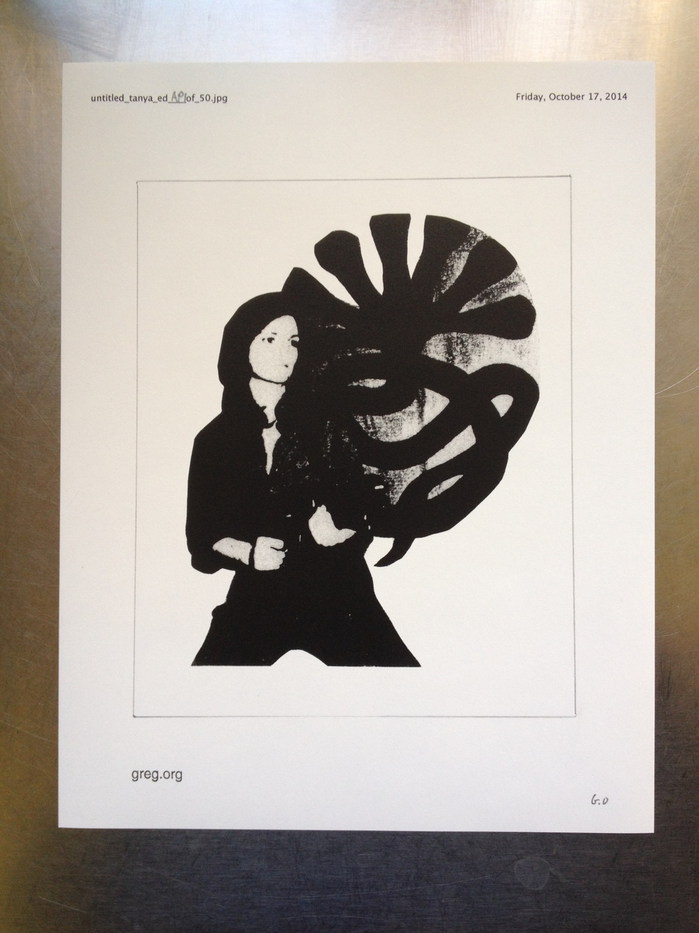

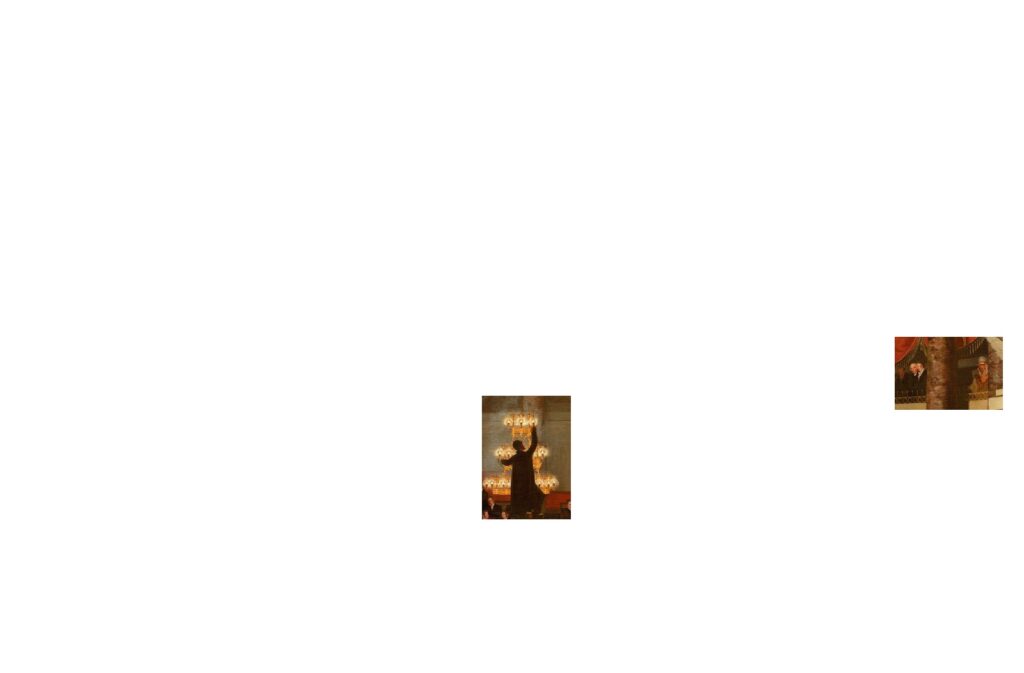

As much as I thought I’d leave Facsimile Objects in 2021, I realize that the Spice DAO Community needs them. Spice DAO Facsimile Object (S1) presents a perfect, facsimile of Copy Number 5 of Michel Seydoux Presents Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune from Frank Herbert’s Novel. Design by Jean Giraud. Machines by Chris Foss. Special Effects by Dan O’Bannon. Dialogue by M. Demuth and A. Jodorowsky, as it was sold at Christie’s on November 21, 2021. Printed at full-size, in high-gloss dye sublimation pigment on an 11.5 x 15-inch aluminum panel, the Facsimile Object embodies the true octavo (210 x 295 mm) presence of this historic, physical, artifact. It is accompanied by a similarly full-scale, handmade certificate of authenticity, executed in ink on handmade Arches paper, signed, stamped and numbered, and will ship in a handmade case.

Unlike previous Facsimile Objects, which were created for the world, Spice DAO Facsimile Object (S1) is only available to verified hodlers of Spice DAO governance tokens. The first 10 verified orders will be priced at 0.5ETH, payable in USD at the ETH/USD price on coinbase for the date of purchase. After that, the price will increase to 1.0ETH. Availability of Spice DAO Facsimile Objects (S1) will continue until morale improves. DM or email to get started.

[update: the price of the Facsimile Object is after taxes. Whether you sell ETH to buy the Facsimile Object, at whatever your basis, or you use your pre-existing fiat is not relevant, and greg.org will not pay your capital gains taxes. Thank you for your understanding.]