We took the kids to the Met yesterday, and in one of the period rooms in the Wrightsman Galleries, which I’d probably been in a hundred times, at least, one kid goes, “Is that a dog house?”

Why yes, yes, it is, and not just any dog house. This kennel, carved in the 1770s by Sené in gilded beech and pine and upholstered in silk and velvet, is stamped GARDE MEUBLE DE LA REINE. It is Marie Antoinette’s dog house. One of just three pieces of furniture belonging to the queen in the Met. The Wrightsmans bought it in 1960, but didn’t give it to the Met until 1971. Guess they wanted to use it for a while themselves.

But wait, Aestheticus Rex has a post about two other 18th c. dog houses in the Wrightsman collection–and a mystery. These two were apparently part of the Wrightsmans’ gift to the Met, but were then returned to the donors. [To be sold in 2010 at Sotheby’s, the hook for AR’s post.] And there is some curatorial ambiguity about the provenance of the above house, for which research is apparently lacking, but which nonetheless remains on view. Decades or centuries later, the gossip of the court continues on blogspot.

Dog Kennel, c 1775-80 [metmuseum.org]

Abstract In Concrete (1952), The Making Of

Nayland Blake just posted this on his always eye-opening tumblr Knee-deep in the Flooded Victory. Abstract in Concrete is a 10-minute short film by John Aravonio, which pairs reflections of neon signs in the rain puddles of Times Square with a jazz/classical score by Frank Fields. The date given on this recent YouTube upload is 1954. And it is credited to the United States Information Agency.

Which is just nuts.

Continue reading “Abstract In Concrete (1952), The Making Of”

Cy Twombly’s Gerhard Richter

RO/LU has the photos of Cy Twombly’s palazzo from that 1966 Vogue feature, and hey ho, he had a Richter. How’d that happen?

Richter had shown Frau Marlow (1964) in his earliest exhibitions: at Galerie Schmela in Dusseldorf and the Capital Realism group show at Rene Block in Berlin. Twombly had been in a 2-person show with Rauschenberg in Dusseldorf in 1960, and the Venice Biennale in 1964, and so on. But I guess I wonder how Twombly came to own a painting by the just-emerging Richter.

Frau Marlow wasn’t seen in public for 35 25 26 years, until 1991. #math.

Frau Marlow CR:28, 1964 [gerhard-richter.com]

UPDATE Thanks to Wayne Bremser for the prodding me to click through on 032c’s 2010 feature on Twombly’s interiors, as photographed by Horst, and as re-energized by Joseph Holtzman in nest. I miss nest.

Also, this classic Mondo Blogo roundup of photos from Horst’s Twombly shoot.

Roland Barthes On @TheRealHennessy Tweet Paintings

In his canonical text, The Death of the Author, Roland Barthes states: “The text is a tissue of citations, resulting from the thousand sources of culture […] The writer can only imitate a gesture forever anterior, never original […] If he wants to express himself, at least he should know that the internal ‘thing’ he claims to ‘translate’ is itself only a readymade dictionary.” Understood in this context, by transcribing @TheRealHennessy tweets onto canvases greg.org sheds light on the dynamics of language, appropriation, authorship and the enigmatic presence of a distinctive voice

@TheRealHennessy Tweet Paintings

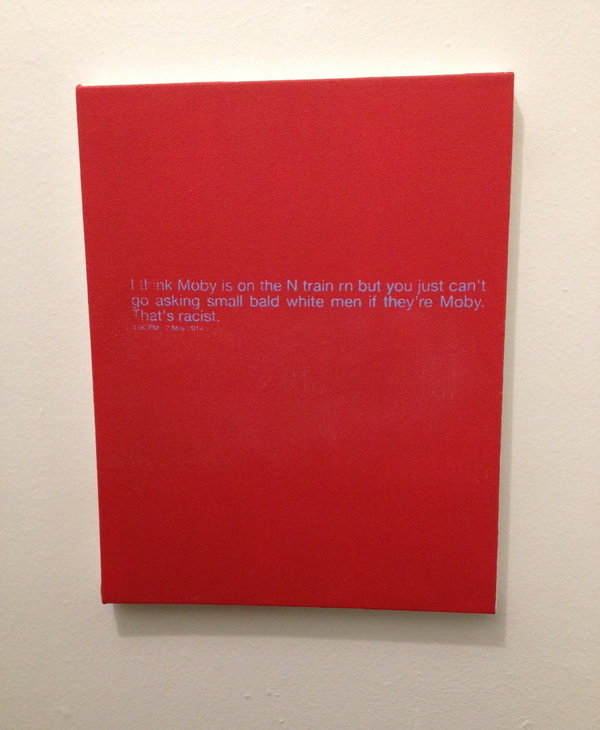

@TheRealHennessy Tweet Painting, Moby, 2014, 14×11 in., acrylic and screenprint on canvas SOLD

If anything I think they’re tragic.

greg.org is pleased to introduce @TheRealHennessy Tweet Paintings, inspired by Donelle Woolford’s Dick Joke series, which were buzzworthy standouts at the most recent Whitney Biennial. update: more here.

Instead of the expressive, gestural application of paint that was so fashionable, @TheRealHennessy tweets are silkscreened onto a flat, monochrome canvas. Similar to his re-photography of existing images, this approach removed the artist’s hand from the work. Despite this conceptual strategy, @TheRealHennessy Tweet works are nonetheless considered first and foremost as paintings. As he jokingly remarked, “the ‘Tweet’ paintings are abstract. Especially in Europe, if you can’t speak English.”

The series of monochrome tweet paintings, of which @TheRealHennessy Tweets, Moby is an outstanding example, presents the viewer with a strangely puzzling juxtaposition of a minimalist canvas and painted words. Although this can be interpreted as a reference to postmodern linguistic theory, the work also points to two quintessentially American features: hard-edge abstraction and popular humor. Cleverly subverting the clean and serious language of abstract painting, the tweets’ amalgamation of low and high culture characterizes @TheRealHennessy Tweet’s most iconic work. This intelligent fusion of conceptual strategies with popular cultural references, which has been the driving force throughout @TheRealHennessy Tweet’s influential practice, is perfectly merged in @TheRealHennessy Tweets, Moby. Wittingly parodying the uncomplicated jokes from vernacular literature, the artist has found a way of incorporating a difficult subject-matter – humor – into a deeply serious artistic practice.

More @TheRealHennessy Tweet paintings are below.

Biography Of On Kawara: 29,771 Days

Most reports of On Kawara’s death place it on July 10, the day the news was made public. I have heard from sources who would know that the artist passed away as much as two weeks earlier. Given the nature of Kawara’s practice, it seems like a non-trivial point to identify the actual date. Given his family’s prerogative and their loss, it seems indelicate to speculate or pry.

As Roberta Smith wrote in her NY Times obituary for Kawara, published today,

Mr. Kawara’s family declined to provide the date of death or the names of survivors, in keeping with his lifelong penchant for privacy.

But she also ends with this:

Keeping the viewer focused on time’s incremental, day-by-day omnipresence was one reason for Mr. Kawara’s deliberately low profile and his habit of listing his age in exhibition catalogs in terms of the number of days he had been alive as of the show’s opening date. In the catalog to a show at the David Zwirner Gallery, an otherwise blank page titled “Biography of On Kawara” put the count at 26,192 days on Sept. 9, 2004. Last week the gallery calculated he had reached 29,771.

When news of Kawara’s death began to circulate, his birthdate, via Wikipedia, was reported as January 2, 1933. Wikipedia’s citation is the Encyclopedia Britannica. But calculating back from the Zwirner show results in a birthdate of Dec. 25, 1932.

The artist’s bio in Henning Weidemann’s book, On Kawara is reported as “(June 9, 1991) 21,351 days,” which also calculates back to Dec. 25, 1932.

Given this birthdate, it becomes clear that Kawara’s family and gallery chose to report, on his own terms, not his death, but the culmination of his life, 29,771 days later, on June 29, 2014.

Update: Now we have a situation. Dia lists Kawara’ bio as “29,622 days on January 15, 2014,” which calculates back to a birthdate of Dec. 10, 1932. Now I feel compelled to cross-check Kawara’s other published biographies. Any citations are appreciated.

The canonical source, such as it goes, would be Kawara’s own 100-Year Calendar, on which he indicates he was born Dec. 24, 1932. Which could mean everything above is off by one day.

According to Weidemann, filling in a dot on his calendar was the very last thing he’d do every day. A green dot meant one date painting. A red dot meant more than one; a yellow dot meant none. It’s conceivable that the artist lived through the 29,771st day, the 28th, but did not complete the 29,772nd. Suddenly, this calculation feels intrusive.

Other biographies:

For the opening of On Kawara 1973 –One Year’s Production at Kunsthalle Bern, his bio reads, “(August 16, 1974) 15 211 Tage.” [Dec. 24, 1932.]

On Kawara Today

News came today of On Kawara’s death, and I’m finding it difficult to articulate much of my own reaction. It’s a sense of profound loss, coupled with naturalness, a frustrating mix of the inevitable and the unexpected.

The kids and I just painted new Today series paintings yesterday, to update the ones they painted for me in 2012 as preparation for RO/LU’s Today series project at the Walker Art Center. So we’ve had On on our minds.

And of course, the Guggenheim just announced that the artist was collaborating with curator Jeffrey Weiss on a full-scale retrospective set to open in February. And I fired off some exuberant tweets about getting my turn in the booth to read for the One Million Years project.

And my recent foray onto tumblr had reminded me that I have to reinstall fromnowon.us, the project we announced during RO/LU’s Walker residency, of commissioning Chinese Paint Mill to continue the Today series, first to fill in the days when Kawara himself didn’t complete a painting, and then to open the project up to everyone when eventually, some day, far in the future…

This idea had struck me during Kawara’s huge 2012 show at Zwirner’s, which had Today paintings from four decades and dozens of cities. The newest painting was Jan. 3, 2012, just three days before the opening. And other paintings appeared during the show’s run, though the artist himself, of course, did not. But Lei Yamabe wrote in the catalogue that on those days when Kawara did not complete a painting, he was like Schrodinger’s Cat, “shut in the closed room of time, simultaneously alive and dead.” And, most alarmingly, and unexpectedly, at least for me, that “the series will be complete when Kawara’s body ceases to exist.”

Damien Hirst had just floated the possibility that his spot paintings could continue into infinity, and frankly, the idea that Hirst would persist and Kawara would not felt devastatingly wrong. Thus, fromnowon.us. But I think the project only gelled because I really didn’t imagine Kawara not continuing himself. Yet now here we are, and now here he is not.

On Kawara’s 2012 Zwirner show was the only exhibition I’ve ever had to walk out of due to overwhelming existential dread.

— Rachel Wetzler (@rwetzler) July 10, 2014

Rachel’s tweet shows, not everyone was as impervious as I, was but reading back a bit today, I see the shadows of non-existence throughout Kawara’s entire practice, which I either ignored or relegated to an abstraction before. In 1991 Henning Weidemann wrote that “the picture of a past date becomes a memorial,” and the very title “lead[s] us to suppose that for the spectator it will always be a question of a “Yesterday”-series.”

Even when using the speediest means of communication available to him in 1970, the telegram, Kawara’s I am still alive was fraught with contradiction:

In a certain sense the phrase “I am still alive” can never be sent as it cannot be received by the addressee instantaneously…It is only valid at the very instant that it is being written, and in the very next second it no longer is a certainty. If the addressee receives the telegram a few hours or days later and reads it, he merely knows that the sender was alive at the very instant the telegram was sent. But when he is reading the telegram, he is totally uncertain if the content of the text is still relevant or if it is still valid The difference, the small displacement between sending and receiving, is that particular unseizable glimpse of the presence of the artist. Likewise, it is a sentence of self-reassurance…”I am still alive.” The activity of telling oneself and the world “I am still alive.”

Now the uncertainty is removed, and that difference, that once-small displacement, will stretch into history. In fact, it’s already bigger than we first thought. I’ve heard from a couple of folks that know that Kawara actually passed away as far back as two weeks ago, after some period of difficulty, but that the artist’s family had requested his passing not be made public before now. [update: according to this calculation, Kawara’s 29,771th and last day was June 29, 2014.]

And so our paintings, my exuberance about the Guggenheim announcement, my continued procrastination, it all went down when I [we] only thought Kawara was still alive, when in fact, he was not.

For some as-yet unknown time, all but Kawara’s close friends and family thought he was still possibly/probably alive, shut in that closed room of time, but he was not. This specific moment, this window, this condition, of knowing something that turns out no longer to be true, feels significant in ways I cannot pin down right now. I’ll think about it every time I see my kids’ paintings, which are now not prescient memorials of Kawara’s own last full day, but which instead mark the last day of our thinking he was still alive.

But it also highlights an important distinction that’s so often lost, especially here, between the artist and his practice, the human being and his work. Just a couple of weeks ago I wondered if Kawara’s family or lover or the deli guy was included in I Met, or was it just his work contacts.

Kawara had a wife, and at least two children. He lived on a street in SoHo. He had neighbors. Kawara didn’t give interviews or talk about his work, but when Nick Paumgarten called about a young Leo Koenig crashing at the Kawaharas’ loft, On answered the phone and gave a quote. Kawara’s work marked one man’s passage through time, space and society, and the end of that project which has inspired me for so long makes me sad. But these were “the traces left on paper and canvas,” as Yamabe wrote, “the shadows that Kawara cast.” For others who shared Kawara’s life, he was a husband, a father, a friend. 謹んでお悔やみ、申し上げます。

2016 update: as time passed, I thought about this project more and decided not to pursue it. after a couple of years, I have taken the unusual (for me) step of letting the domain name expire. I still think about Kawara’s work often, and it is possible that a related project responding to it might arise in the future. But not right now.

Previous Kawara on greg.org:

On Kawara Data

On’s Location

Setting: Fredericianum, Documenta 11 | The voice of a woman reading from within a freestanding glass booth echoes

Richard Meier’s Fire Island Houses

[2018 UPDATE: In 2018 The New York Times reports that five women who worked with Meier, either at his firm or as a contractor, have come forward to say the architect made aggressive and unwanted sexual advances and propositions to them. The report also makes painfully clear that Meier’s behavior was widely known for a long time, and that his colleagues and partners did basically nothing to stop it beyond occasionally warning young employees to not find themselves alone with him. This update has been added to every post on greg.org pertaining to Meier or his work.]

Suarez House, Richard Meier, 2012-13, photo Trevor Tondro/NYT

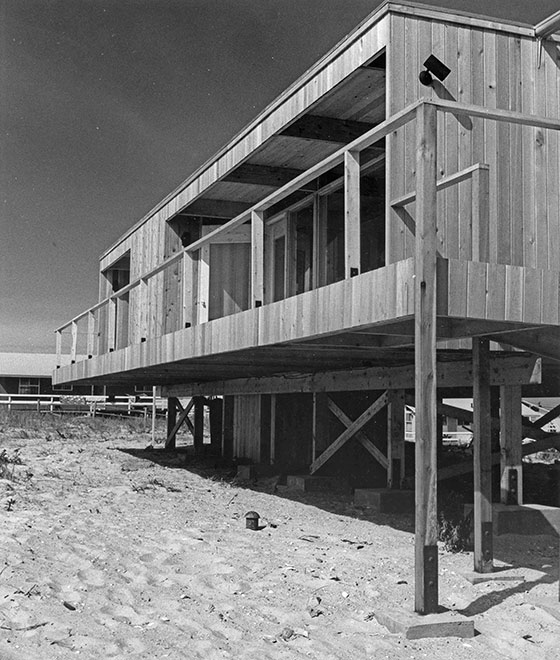

It’s the funniest thing, just last night I was thinking about Richard Meier’s first house, which he built on Fire Island in 1962. And lo and behold, Meier’s second Fire Island house just turned up on the front page of the Home section of the Times.

The Times says “it was like coming full circle,” but honestly, if the projects show anything, it’s how far Meier has traveled in the intervening 50 years. The 1962 house, built for Saul Lambert, was a prefab box, assembled in a couple of weeks from a pile of lumber cut to order by a log cabin manufacturer in Michigan. The 2012 house, built for Phil & Lucy Suarez, is a 2,000-sf steel and triple-glazed cube which the contractor called “a little skyscraper,” and which the Times dubs “Meier’s high and mighty beach house.” It’s basically a penthouse from Meier’s West Village towers, plopped down amidst the scrub oak and stick shacks of Fair Harbor.

Which is not to say it doesn’t look great. 2,000 square feet turns out to be plenty to get the full Meier Effect.

Lambert House, Richard Meier, 1961-2, image via architect/NYMag

But call me old-fashioned, I really like his first house best.

The Lambert House is special for me because it was one of the first obscure things I dug up. An architect friend, Chad Smith, had noticed an interview with the actress Anne Bancroft, where she mentioned living in a shingle-clad Meier beach house with her husband Mel Brooks. Which set off some cognitive dissonance. So I started Googlediving and turned up more info on the oceanfront house, which was in Lonelyville.

Over the course of a couple of days of back and forth, Chad wrote about the Lambert/Brooks/Bancroft House on his architecture blog; and he heard from neighbors, and eventually, from the house’s current owners, who shared stories and pictures. It was a somewhat euphoric process, connecting these blog worlds to the real world, and pushing information, then knowledge, out there.

Chad was stoked, too, and kept up conversations with the owners for a while, maybe floating the idea of a renovation, but I don’t think anything ever happened. For my part, it was too soon so speak ill of the dead in 2006, and though Mel Brooks is still a genius, let’s face facts: between the shingles, the second story, the rooflines, the doors and cut-out windows, the add-ons, and on and on, they completely ruined Meier’s design.

The only proper thing to do is to strip the house back to the original box.

I mean, just look at it; there’s nothing there, and it’s perfect. How many times has this exact open-plan, 2BR house been designed by prefab-loving modernists on a budget in the last 50 years? It’s the Glass House made out of 2-by, on stilts. Anyway, I resolved [again] last night to earmark my 15th, but certainly no later than my 20th million toward buying Richard Meier’s first house and restoring it to its stripped down glory. And if someone beats me to it, that’s probably fine with me.

Richard Meier’s High and Mighty Beach House [nyt]

The Artist And The Frame

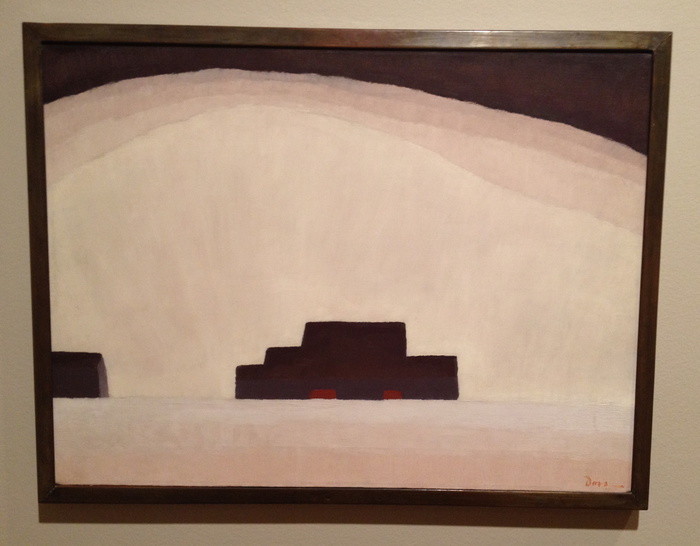

Arthur Dove, Snow Thaw, 1930, phillipscollection.org

In this interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Franz Erhard Walther talks about becoming interested in the early 1960s in frames:

The original idea was to have a frame with nothing in it. It asked the spectator to project his or her idea, image, object, whatever. So, a projection field. Through the decades, it’s a main theme for me, working with a frame, and the idea of projection, filling the frame by imagination.

Which I find particularly interesting because I’ve been looking at just the opposite: artists who paint frames around their work.

Stuart Davis, Blue Cafe, 1928, phillipscollection.org

Folks like Seurat painted his frames and considered them as integral elements of his works, of course. But at the Phillips Collection a few weeks ago, I noticed that American modernist painters like Stuart Davis and Arthur Dove were painting frames, and painting borders around their paintings. It gives the paintings a sense of self-containment, completion, wholeness, but it also sets them apart. With aluminum strips on each side Dove gave one later collage a window effect. ANd Davis did some kind of frame treatment on nearly every painting in the Phillips. [And on prints, the border of the paper beyond the stone serves the same formal function.]

I imagine it was something early modernists had to take on themselves because they didn’t want some collector or dealer slapping a pie-crusty traditional frame on there. It was a control thing. But also a gesture of breaking with the norms of the established painting and art world of their day.

In either case, frames were still the place where the terms on which the artist’s work met the world were set.

Also, I just love this Dove painting, even more than the many great Doves in the Phillips collection.

Nice Grouping

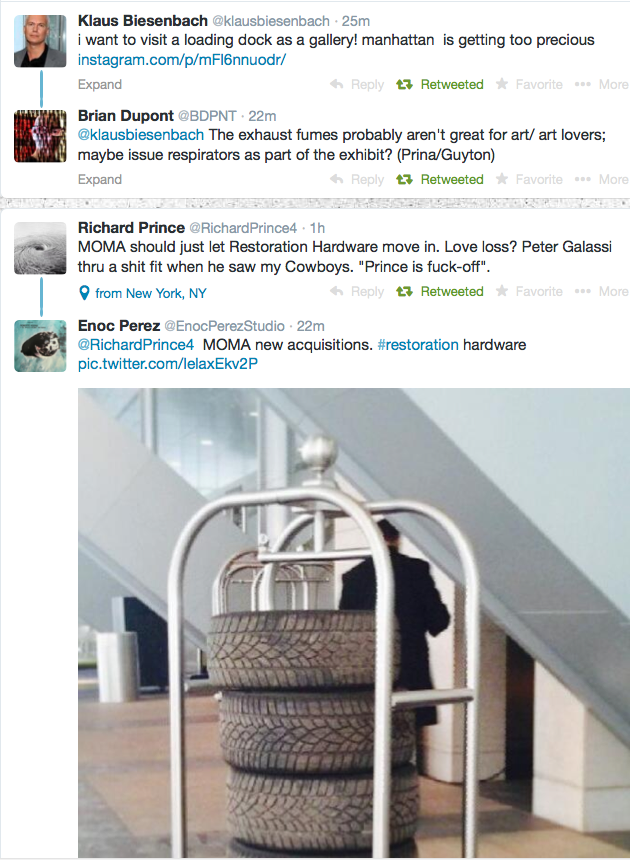

very nice grouping (loading): pic.twitter.com/3B5gACypBi

— gregorg (@gregorg) March 28, 2014

I’ve began noticing these twitter juxtapositions about 18 months ago, and have been collecting and occasionally retweeting them since last fall.

Now I’ve put these groupings together in one place, to see what to make of them. At grpg.greg.org, I’m caught up through April, and will start functioning in realtime in a week or so.

When I first started, I connected these abutments of random images and texts to, of all things, the upload scene in Johnny Mnemonic, where Keanu tells the renegade Japanese pharma chemists to encrypt the data by capturing three images from the television.

But I just rewatched that scene now, and it’s meaningless, also hilarious. First off, they print hard copies and then fax the three images to Newark? Don’t get me started. Anyway. That is definitely not important now, but I am interested to see how these things look together.

grpg: nice grouping [grpg.greg.org]

Readymake: And You May Find Yourself 3-D Printing A Marcel Duchamp Chess Set

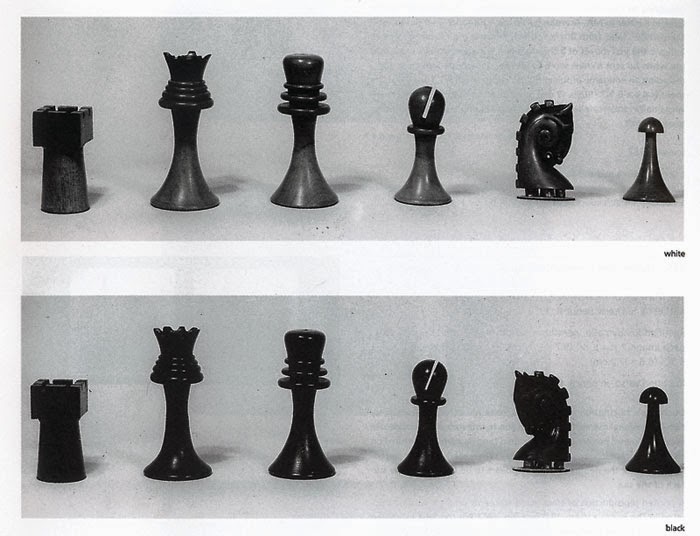

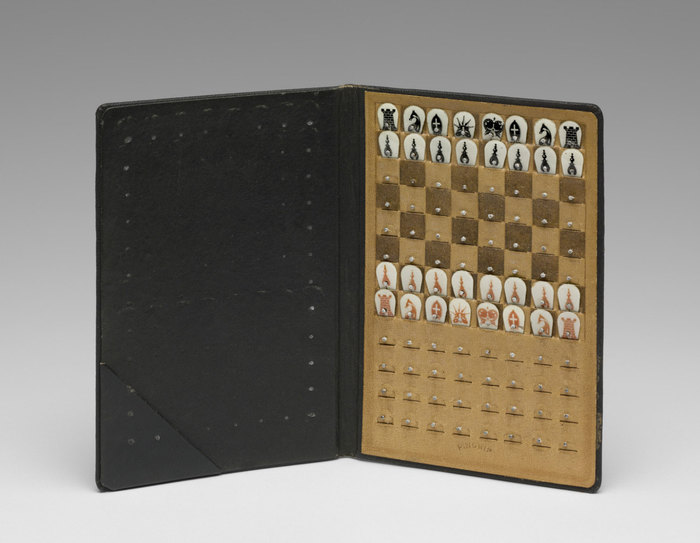

A couple of years ago Scott Kildall created Playing Duchamp, an online chess program designed to simulate the chess play of the artist, and incorporating the designs of two of the chess sets Duchamp created over the years.

As a non-chess-player, my own personal favorite is the Pocket Chess Set, 1943, which he planned as a mass market product, but which ended up as a limited edition. [The image above is from the example the Arensbergs donated to the Philadelphia Museum.]

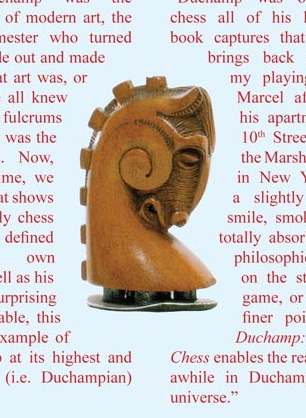

But I also like the sleek, Art Deco-inspired set Duchamp had carved in Buenos Aires when he arrived there in 1918-19. The knight especially reminds me of the Futurist-ic Horse sculptures of Marcel’s brother, Raymond Duchamp-Villon.

Anyway, Kildall has collaborated with Bryan Cera to recreate Duchamp’s Buenos Aires chess set from archival photos, and to release them as 3D-printable models. The first draft was uploaded to Thingiverse a few weeks ago. Titled Readymake, the Duchamp Chess Set has already been printed in several media and finishes by Makerbot community members. They look pretty sweet. [That’s Cera’s image of his proof set above.]

Cera writes that his and Kildall’s concept was “resurrecting objects [like the Chess Set] that have been lost…This set no longer exists save the archival photograph pictured above.” Well, and this photo:

And the chess set itself. This pic’s from a 2008 Duchamp exhibit at the Fondacion Proa in BA, that lists the chess set as belonging to a private collection. And Francis Naumann included the set in his 2009 exhibition, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess in New York. [UPDATE: He did not.]

No problem: if the set was not exactly lost before, thanks to Cera and Kildall’s project, it is now much easier to find.

UPDATE:

No, there is another. This carved knight on the page for Francis Naumann’s exhibition catalogue, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Chess, is different from the “lost” Buenos Aires set.

Please don’t make me dig out my copy of Naumann’s catalogue raisonnesque Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction to figure this out…

2019 UPDATE: Or do make me dig it out. Because I’d based my assumption that the knight above was too light to be from the set depicted up top, but Naumann uses the same photo with better balance, and it’s entirely plausible. Also there is zero mention of another set. So I would have been less wrong for five years had I checked the book. [Thanks to reader jp for asking wtf I was referring to.]

Readymake: Duchamp Chess Set [kildall.com]

Resurrecting Dead Objects [bryancera.blogspot.com]

Uncle Sam’s Club

The Department of Homeland Security released this photograph of Secretary Jeh Johnson and Arizona Governor Jan Brewer and their respective entourages visiting the Males 16-17 aisle in the Nogales Placement Center, where several hundred ? thousand? unaccompanied minors are being detained, after being arrested while crossing into the US.

I’m going to be Gurskying up images of these juvenile prison warehouse stores as I find them. I just cannot even right now.

Readout of Secretary Johnson’s Visit to Arizona [dhs.gov/news]

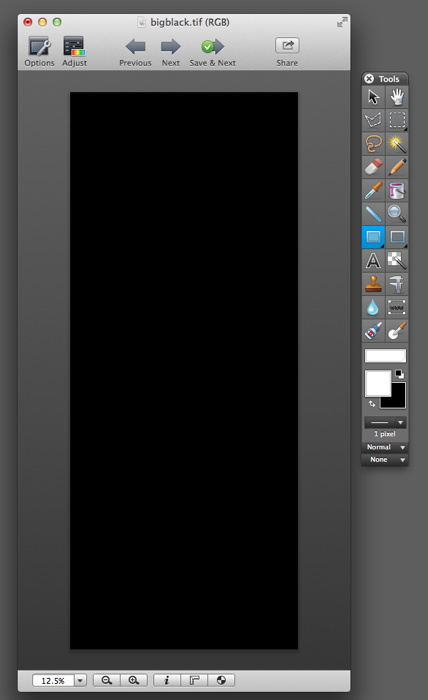

bigblack.tif (after Wade Guyton)

Here you go, now you can print yourself a whole art fairful: bigblack.tif (after Wade Guyton), 2014. [dropbox greg.org, 45mb]

It’s The Little Differences

A couple of commentators crystallize what is becoming the conventional wisdom about Wade Guyton’s Instagram provocation last month, a few days before one of his paintings headlined a heavily hyped sale at Christie’s. It’s the idea, first expressed by a giddy Jerry Saltz, that Guyton is trying “to tank his own market by flooding it with confusing real-fake product.”

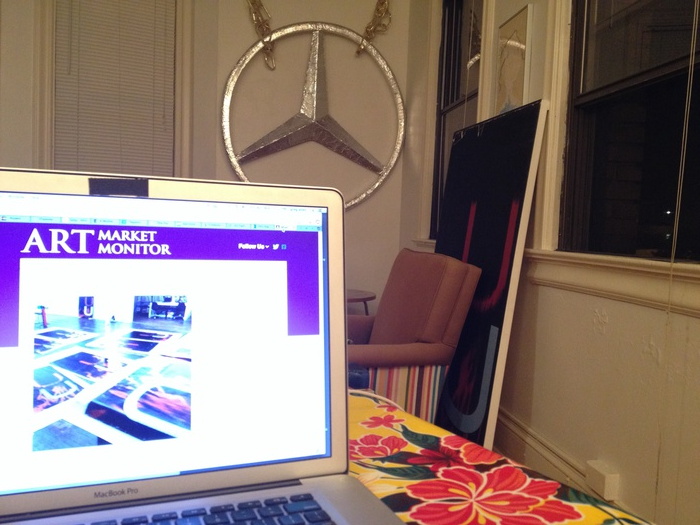

Marion Maneker expressed concern that the Guyton’s “threat” to create “a whole series of works from the previously unique printing of an image file” had backfired, and if we were all obsessed with his market now instead of his work, it’s basically Wade’s fault. From Art Market Monitor:

It’s hard to tell whether Wade Guyton is inadvertently steering the conversation away from his art and toward his market or whether the artist has simply fallen prey to the Barbra Streisand effect where the more one tries to deflect attention to an event, the greater the interest.

I just don’t buy it.

As Guyton’s own Instagram photo above showed, the Times [and Christie’s themselves] had already made him the poster child for anxiety marketing for a auction that was actually full of guarantees and third-party pre-bids. If Guyton really wanted to destabilize his market, he could just pull a Cady Noland and demand the auction house remove his name from a work. This did not happen. Instead he reaffirmed the central element of his practice: that his paintings are each machine-printed renderings of infinitely reproducible digital files, whose uniqueness derives from the circumstances of their production. And record resale prices continued apace.

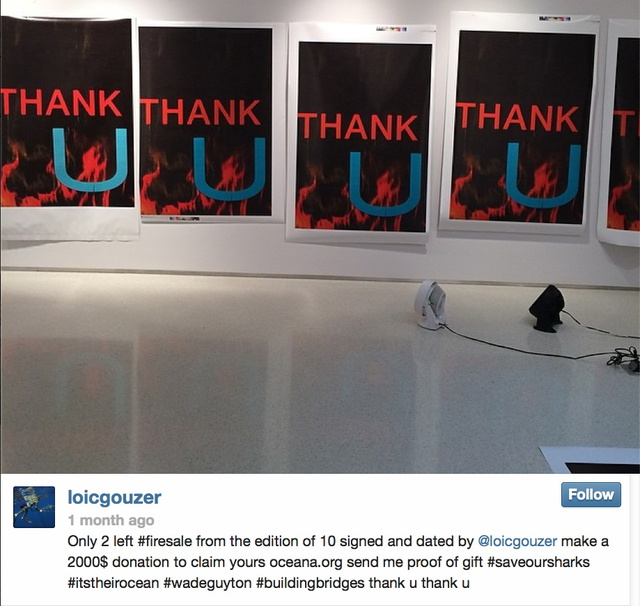

[How uncontroversial was Guyton’s backup copy situation? Christie’s auctioneer Loic Gouzer made–and signed–his own batch and sold it as an edition of 10, with proceeds going to Leonardo diCaprio’s favorite shark conservation charity.]

If it did anything, Guyton’s Instagram posts served as public critique of the Auction Week hype. It was a way to align himself critically against the system of relentless commodification–and to inoculate his work against the charges of speculation and cynicism that are leveled against auction stars. Even while his work was jostling around in the center of the hypercapitalist scrum.

Perhaps it’s not fair to blame Maneker for toeing Carol Vogel’s NY Times line, but he did it again in the very next paragraph, about the art market’s very next get-together. In her Art Basel roundup, Vogel made a lot of hay about Guyton giving each of five dealers “a black painting, all the same size and all made from the same disk.” Guyton calls it “a way of talking about the repetitive experience of seeing similar artworks throughout a fair and embracing that aggressively by showing almost identical works.”

Which is taken by Maneker to be the artist’s “ploy” to “orchestrate his market” and emphasize the arbitrage-friendly chasm between the insider/primary vs speculator/secondary channels. Except that’s exactly how almost every artist deals with auction spikes, as any art market monitor would know.

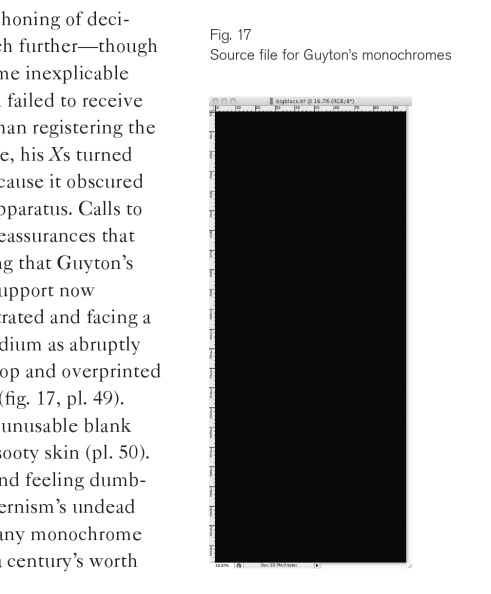

And there’s another salient fact that’s missing: Guyton makes all his black paintings from the same “disk,” or as we call it nowadays, a “file.” It’s called bigblack.tif, and there’s a screenshot of it in Scott Rothkopf’s essay for the Whitney’s 2012 OS exhibition catalogue.

installation view, 2008 Black Paintings show, Galerie Chantal Crousel

And he makes them in groups that at first seem indistinguishable. In 2007-8, he made three shows in a row, at Friedrich Petzel (NY), Chantal Crousel (Paris) and Portikus (Frankfurt) of nearly identical black paintings, installed identically. Just this spring, he recreated his entire 2008 show at Crousel, black plywood floor and all. Everything was the same. Except for the things that weren’t.

installation view, 2014 Black Paintings show, Galerie Chantal Crousel

John Kelsey wrote in the 2010 Black Paintings catalogue:

What this work displays is the difference between sending information and receiving aesthetic objects in the gallery, or what happens when “black” moves from desktop to printer to museum, and whatever is lost along the way. The monochrome is a record of circulation. As it is copied and communicated, discrepancies are produced. And these are what now stand in for painting.

Guyton: it’s the little differences. And those are precisely what is lost when paintings are seen one at a time, in auction catalogues, art fair slideshows, and drifting by in infinite Instagram scrolls. Guyton’s inky black paintings cast a harsh light on the impoverished experience of art-as-shoppertainment, of paintings decontextualized from the artist’s practice and the flow in which they were conceived, and remerchandised as, well, merchandise. Paintings remain ruthlessly efficient units of exchange even though they’re often no longer optimal units of aesthetic experience. That divergence marks what’s lost when painting becomes nothing more than, as Ben Davis’s timely quote of John Berger puts it, “a celebration of private property.”

But it also marks a shift in artistic practice. Guyton’s just one of many artists who create on the scale of the series, the installation, the context, the network, not the lone object. Rather than throw up his hands, or lalalala pretend it’s not happening, Guyton’s recent actions show him to be conscious of the art market’s experiential crisis, and actively seeking out a way to engage or overcome it without throwing his paintings on the fire.

The Red-Blue Proposition

The late Danish artist Albert Mertz spent decades working with what he called “The Red-Blue Proposition.”

Mertz died in 1990, and was reincarnated as a YouTube video uploading quality assurance tech at Google Zurich.

Albert Mertz, ‘Watch Red-Blue TV,” Jan-Mar 2014 [tifsigfrids]

image of unidentified installation via art blog art blog

Previously, uncannily related: Webdriver Torso as Found Painting System