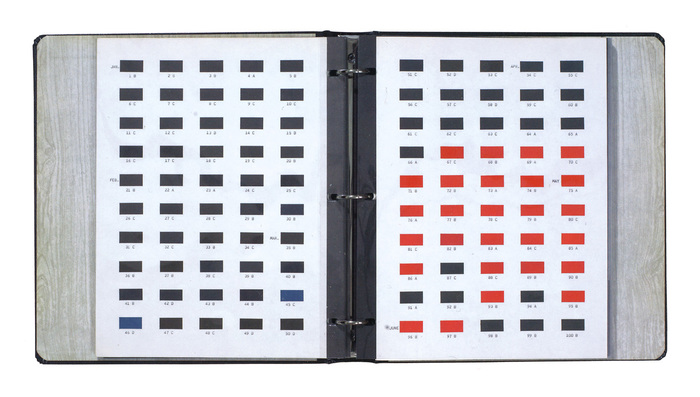

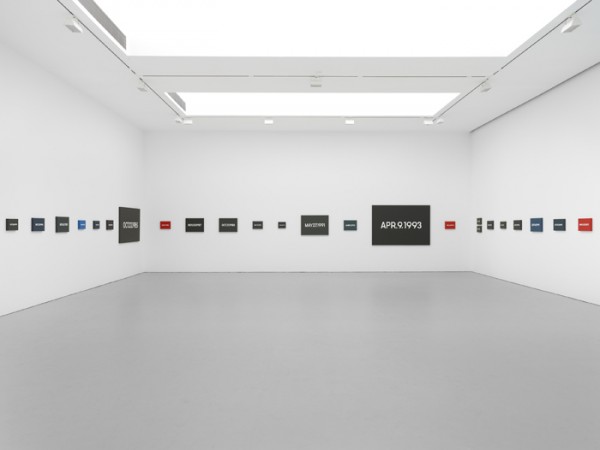

I’ve had this image of a spread from On Kawara’s Journal on my desktop for months now. I love the reduction of the Today Series paintings to desk calendar size. There is one binder journal for each year since 1966, when the series began. [chungwoo has more images and details the content and format of the journal. In Korean.]

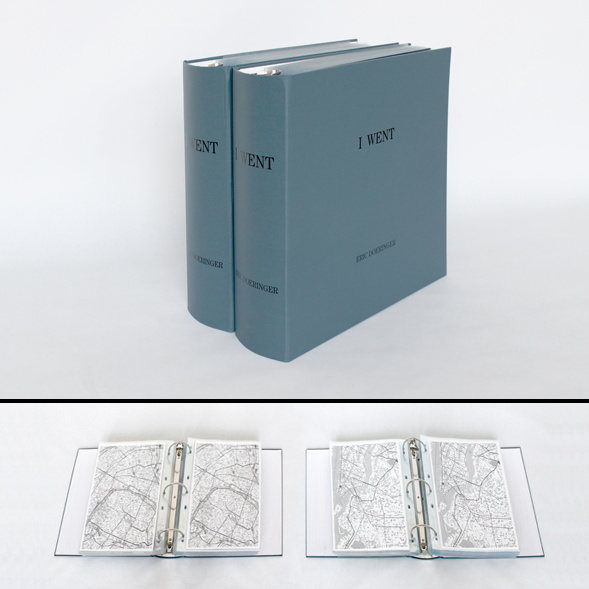

Anyway, while surfing through Michele Didier’s site just now, Kawara’s Trilogy stood out for a couple of reasons. First, and obviously, is its sculptural presence. They look so Juddy, especially with the sliding front covers on.

Kawara’s not necessarily known as a sculptor, but then, it’s not just these boxes, is it? The paintings are objects in boxes, too. And books and binders and CDs, however unreadable their information, always read as physical objects. [The file name on this image even turned out to be on_kawara_boites.jpg,]

Didier published the Trilogy over four years: I Met (2004), I Went (2007), and I Got Up (2008). Each twelve volume set is an edition of 90, with 10 APs. I Met is now only available as part of Trilogy.

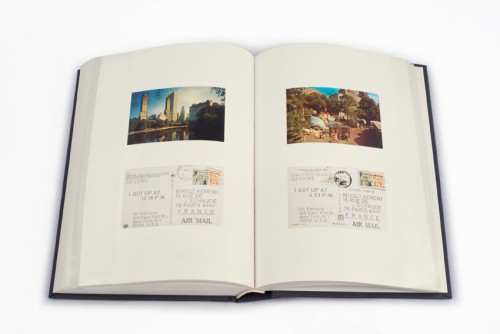

I Got Up, detail. Wait, so will there also be a I Photographed Postcards? How did he get pictures with postmarks? Did he get the cards back? This is no small task. [images: micheledidier]

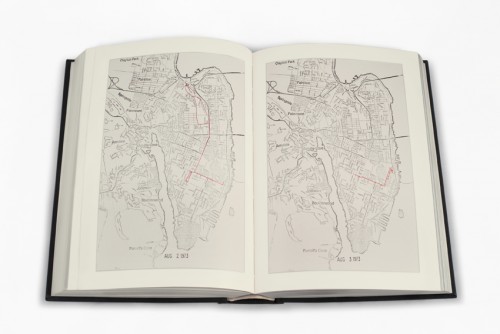

The sets overlap in time, an 11.5-year period from May 10, 1968 to September 17, 1979. Actually, I Went, in which Kawara traces his movements on a map of whatever city he’s in, didn’t start until June 1st. Which now makes me curious. Did it take a couple of weeks to figure out? Did the idea only come once he’d started logging his interactions [the people he met and the ones to whom he sent his wake up postcards]? Did he have somewhere to hide?

Or to use Didier’s term, “the information within [I WOKE UP] intersects with the facts reported in I MET and I WENT.” Information and facts. Data. Kawara was logging by hand exactly the kind of information our computers and phones now track automatically. As metadata. For Kawara, metadata is the data. The difference, of course, is that he’s tracking himself, intentionally marking his passage through time and space, and across his social matrix. [btw, does I Met include the cashier at the deli? Does he live in a doorman building? Is his partner in there? His hookups? What do these maps of Kawara’s mindfulness communicate?]

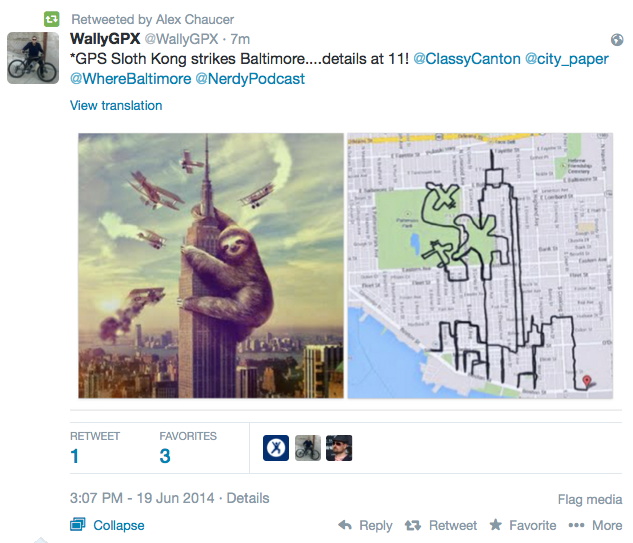

The takeaways here are clear: What IS it like maintaining such total personal information awareness? Since Kawara’s not talking publicly about it, we can turn to Eric Doeringer, who has re-enacted three Kawara projects, including I Got Up (2008-13) and I Went (2010) [above].

Also, who’s going to digitize the 14,000 pages of Trilogy to create the On Kawara Database Beautiful boxes of books are great, but information wants to be free of the box. Why flip through a book when we could be reliving Kawara’s 1970s day by day on Street View? At a time when we’re all unwitting, indifferent, or dispirited subjects of constant surveillance, the lessons of Kawara’s project have never been more important.

UPDATE: Or it might be the exact opposite, hard to say.

On Roman Balls

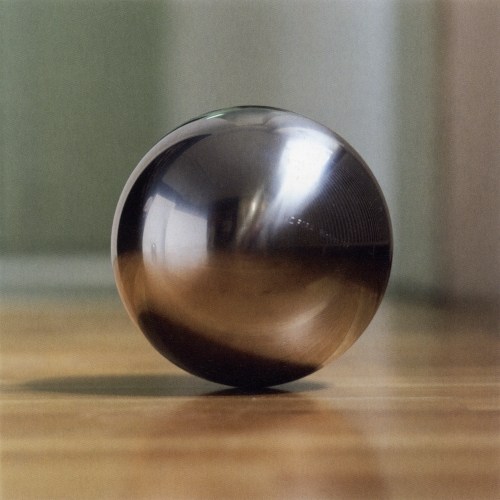

I was looking up something else entirely when I came across this post at the travel blog, Rome the Second Time, an architecture professor explaining how giant balls are a “very fascist” architectural element, which were popular starting in the 1920s.

The photo above is of a fascist-era housing complex in Garbatella, for example, and there are several more great examples.

Which, on the one hand, good to know, because seven years ago, when I first mapped out the world for places that could accommodate showing a 100-foot-diameter satelloon as an art object, the Pantheon in Rome was one of only a handful of possibilities. In concept, in fact, it seems like it’d be the perfect choice. [Eventually the Grand Palais in Paris joined the list, too.] But if spheres read to Romans as fascistic artifacts, you’d need to take that into account.

The perfection the fascists loved also made Gerhard Richter very skeptical of spheres. He complained that with spheres it’s “impossible to get any closer to perfection,” and so you stop. Except when you don’t; 16 years after he said this Richter created his own shiny steel sphere editions.

The Balls of Rome [romethesecondtime]

previously:

If I Were A Sculptor, But Then Again…

Les Sateloons du Grand Palais

Shiny Balls by Gerhard Richter

It’s Hard To Keep The Cowboys Straight

Republicans: Gays, Drunks, Let God Sort’em Out, image: AP/Rex C. Curry via TPM

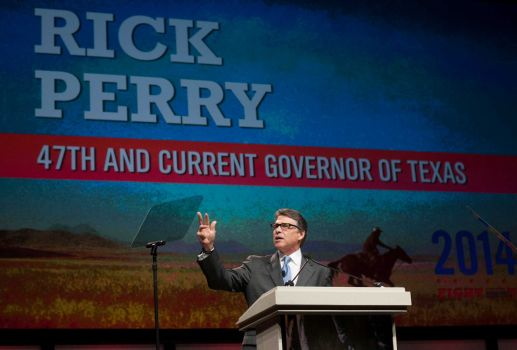

Yesterday I tweeted about Texas governor Rick Perry wearing his “Smart Glasses” and standing “in front of a Richard Prince mural” in San Francisco where he was condemned for comparing homosexuality to alcoholism.

This morning Mr. Prince tweeted the following, which, like most tweets that don’t mention me, I assumed to be about me:

Getting blamed or credited for everything Cowboy. “Whoever it is, wish they’d cut it out quick. When they will I can only guess”.

— Richard Prince (@RichardPrince4) June 12, 2014

Upon further review, it turns out the photograph of Governor Perry was actually taken last Thursday at the Texas GOP Convention in Fort Worth, where the party was condemned for endorsing anti-gay “conversion therapy.”

images ap/ray c. curry via chron

The image projected behind Gov. Perry is Lone Rider, Texas, a 1974 photo by William Albert Allard, originally published in National Geographic Magazine.

detail of “West Texas Cowboy,” Allard’s National Geographic wallpaper

It is one of the first five results on Google Image search for “texas cowboy riding,” and given the saturation levels and pixellation, I suspect Gov. Perry’s people got their jpg from the National Geographic wallpaper collection and cropped out the copyright info and logo,

and not from the C-prints for sale in Allard’s gallery.

Allard was one of the original photographers for the Marlboro Man and Marlboro Country ad campaigns after they switched from models to real cowboys in the 1970s. Prince would begin rephotographing these print ads around 1980. As far as can be discerned, this image has not appeared in a Marlboro ad, and has not been rephotographed by Mr. Prince. Yet.

greg.org regrets the error.

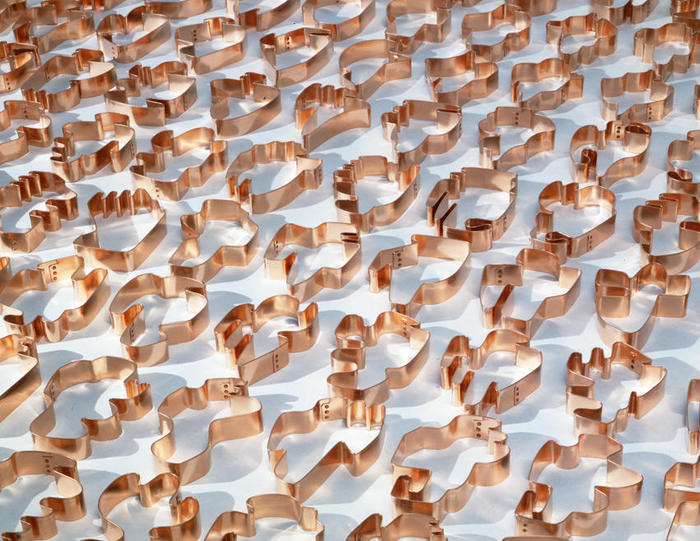

Danh Vo On ‘We The People (Detail)’

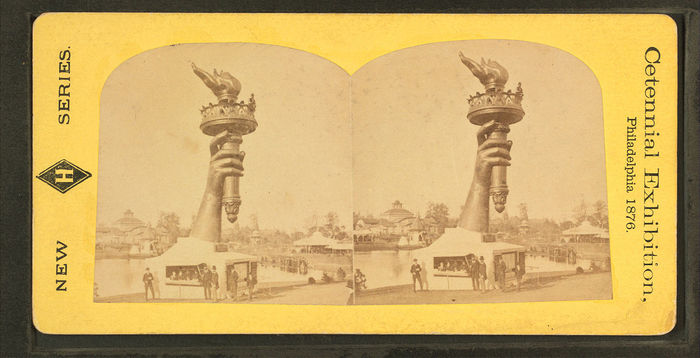

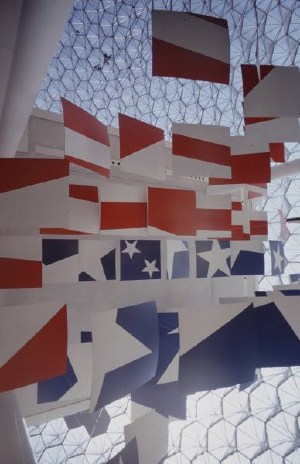

Here is an interview [in Danish, subtitled] with Danh Vo, on the making and exhibition of We The People (Detail), his full-scale copy of the Statue of Liberty. Many of the 400+ pieces of We The People were rotated and stored at the Statens Museum for Kunst in Denmark in 2012-13.

I am enthralled with this work; it strikes me as one of the smartest, most elegant, and provocative sculpture projects in years, and yet it didn’t occur to me until Vo mentioned it that Gustave Eiffel, who designed a steel armature to support Bartholdi’s copper repousse skin, did not see the Statue of Liberty installed in the US.

But reading up on the Statue’s history, it turns out the entire statue was assembled in Eiffel’s factory in France, and then disassembled for shipping. Also–and I did know this and should have remembered it–the statue began as parts, exhibited. Bartholdi made the statue’s arm and torch, which traveled to the US for the 1876 US Centennial, and which remained installed in Madison Square Park for several years afterward. And the head was exhibited at the Paris World’s Fair in 1878, all as part of a fundraising, promotional effort for the project.

SMK TV: Danh Vo – We the People [smk.dk youtube via @aservais1]

Stapler Man’s Identity Is Unknown To This Day

Rohit Mahajan tweeted tonight that this was one of the images deleted from Weibo on June 4th. It’s an amazing photo, though apparently not amazing enough to elude interpretation.

If I’m reading this correctly, it also seems that the weibo user, with the name Freedom Abib/barkcheekhandle is posting from the US, not from within China. FWIW. morning after update: and now the account, which I’d seen via the tw.weibo.com site, has been deleted.

[via @heresrohit]

Force Luke The Use: Star Wars Alphabetized, By Tom 7

OK, this is quite good. Tom Murphy 7 just released ARST ARSW, all the dialogue of STAR WARS Episode IV: A New Hope re-edited into alphabetical order.

I just watched the whole thing while clearing my inbox, and it is surprisingly interesting. Surprising, I guess, because the concept’s instant graspability seems seductively complete. You think you get it.

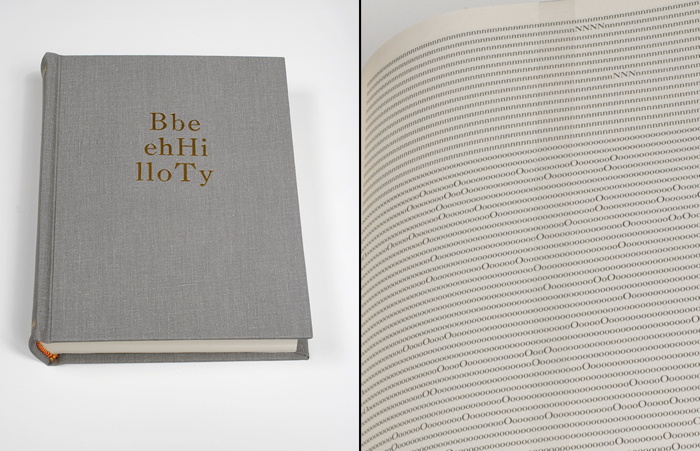

Tauba Auerbach’s Alphabetized Bible (2006) [above] is a bit like that. By alphabetizing the letters instead of the words, Auerbach atomizes not just the meaning of the text, but any hope of meaning at all. It becomes an object made of symbols, signifying nothing.

But that’s not what Tom 7’s film turns out to be. Even chopped so finely, the text, plus the film image and sound, still carry a lot with them. And since the fulltext of Star Wars saturates people more fully than the fulltext of the Bible, the experience of watching ARST ARWS is one of constant recollection and recognition. It feels like watching an actual movie, even though its structure has been obliterated. Not obliterated, but replaced. And that structure turns out to have surprises, tension, and meaning of its own.

To be honest, it starts out slow and kind of muddled with “a,” a word that barely gets its sound right in 201 citations. The first real drama, as Kenny Goldsmith noted, comes with the 20 mentions of “Alderaan.”

I did not expect it, but “hey” [19], “here” [67], and “there” [51] were very exciting, appearing in scenes of recognizable cinematic immediacy.

“Father” [12] was almost always said with unhurried purpose, which makes sense, but not with any systematic foreshadowing, which would have been brilliant. [And not beyond notice. According to Wookieepedia, Lucas tweaked the audio in a line of Aunt Beru’s for the 1997 Special Edition: “The line ‘Luke’s just not a farmer Owen. He has too much of his father in him.’ There is a slight pause before she says father and the word “father” is changed to sound more worrisome.” There are, however, no pauses in ARST ARSW, so this change is difficult to register here.]

And there are a couple of standout solos [no pun]: C3PO’s “sir” [44] aria gets a response a few minutes later when mostly Luke mostly screams “Threepio” [13]. And though it’s only said once by anyone, Han really makes “worshipfulness” count. Tom 7 himself notes that “lightsaber” also only appears one time. “Death Star,” meanwhile, is two words, and so it dissolves into “Death” [6, but at least one is “death sentence” from the cantina], and “Star” [11].

Like any good film, ARST ARSW leaves you wondering how it was made and eager to see what comes next. The project has yet to appear on Tom 7’s site, but I expect the making of involved some tricky data scrubbing to sync each word with each clip. I’m guessing the subtitle file was used, but anything beyond that’s still in the movie magic category for me. [update: YOW, in the YT comments, Tom says he labeled all the words manually using purpose-built software!]

What I would like to see, though, is the data. Now that every word is synched to every clip, it can be released for remixing. Turn Star Wars into a database for generating whatever text you can imagine.

This has already happened, of course, with news footage, where there’s a whole genre of YouTube videos of remixed presidents saying things they didn’t originally say. The ultimate example for me is still Dan Warren’s 2011 breakthrough, Son of Strelka, Son of God, a mythical epic woven out of Barack Obama’s audiobook recording of Dreams of My Father.

If Tom 7’s process for turning movies into words can be scaled, we won’t need to stop at Star Wars; we could turn every clip of everything into the raw material for anything.

ARST ARSW: Star Wars sorted alphabetically. [youtube]

Son of Strelka, Son of God, by Dan Warren

For Months He Wanted To Live Between The Billboards

Can I just say how much I like the new aesthetic of the New Jersey Turnpike expansion project? I honestly cannot imagine that many people going to or from the Pennsylvania Turnpike; at least in my 10 years of DC-NYC shuttling, I’ve never seen that kind of volume, but aesthetically, I’m generally for it.

It’s not the only place that has it, and maybe it’s just the standard now in overpass and on- and off-ramp construction, but instead of bulky concrete pillars, the ramps are held up by huge, road-spanning I-beams. They all have a beautiful, oxidizing protective finish, too, like the best Richard Serras.

Even cooler, though, are the new electronic signs, which are constructed of square, Cor-Ten pipe, and they have meshed-in spaces for maintenance. Not just catwalks, or ledges, but actual spaces. What we perceive as a flat thing–a sign–turns out to be a space. Like the window halllways at Grand Central or Philadelphia 30th Street Stations. The Turnpike signs are New Jersey’s newest architectural icons, suspended across that state’s iconic landscape: a 12-lane highway.

And someone designs this stuff. Probably someone at PKF Mark III, the firm which the Turnpike Authority awarded three contracts in 2011, totaling over $44 million, for the “Installation of Variable Message Signs at New and Existing Locations on the Turnpike.”

Oh wait, nope. Here it is, from the NJ Turnpike Interchange 6 to 9 Widening Program website: “Advanced Fabrication of Overhead Span Sign Structures for Variable Message Signs and Variable Speed Limit Signs,” awarded to RCC Fabricators, Inc., on August 13, 2009.

The project was one of the highlights in the 2011 newsletter for the Railroad Construction Company, Inc. family of companies [pdf, img above]. RCC Fabrication made 61 VSM sign structures, 41 for the Turnpike and 20 for the Garden State Parkway. The structures span up to 95 feet, and were built entirely off-site. I can’t tell from the acknowledgements who is actually responsible for this form, but it works.

The architect/sculptor Tony Smith famously described the revelatory experience of driving down the unfinished New Jersey Turnpike in 1951 [pdf]. Me, I would like to move in before it opens. And before it gets too hot.

Previously: Michael Ashkin, “For Months He Lived Between The Billboards”, 1993

Related infrastructure as domestic architecture: That Minnesota Skyway for sale again/still

Mies Gas Station

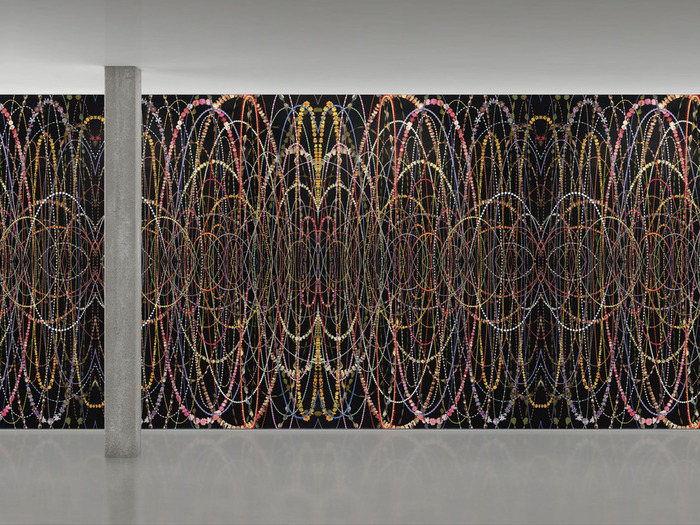

Artist Wallpaper, Anyone?

Has anyone ever bought artist wallpaper from Maharam Digital Products? Or have you ever seen it installed? 1 I’m kind of fascinated to know when, where, and who. Because is it seems to exist in this unusual space between pattern, image and object, between art and decoration. It has that visual punch, but compared to an artwork artwork, it’s pretty cheap. [I think it starts at around $5-10,000 per installation.] Also, it’s consumable, a one-time deal. You can’t take it with you, and perhaps more importantly, you can’t really resell it.

So it really is for love. But it’s also a little weird, like a counterfeit somehow. It feels strange that it’s so customizable, a servicey product. Some artists’ wallpaper feels close to their “actual” work. Some really tried to get into the essence of wallpaper as a tradition and a medium. I’m undecided which is the better approach.

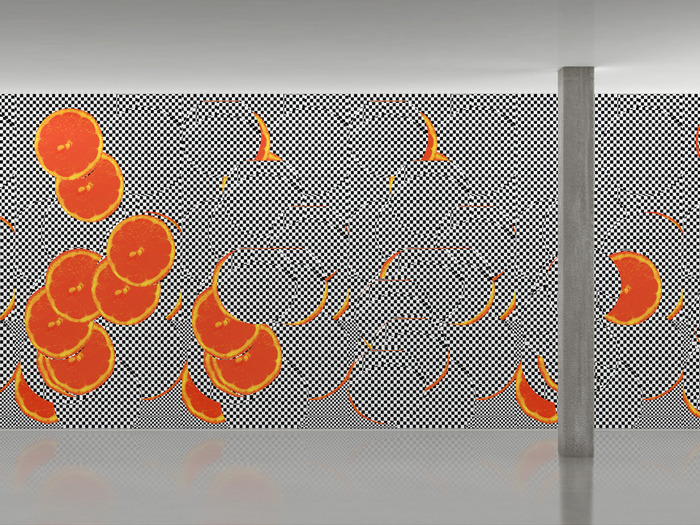

Guyton/Walker’s Orange_Lemon_Chex looks like it came straight out of an installation. But then if you just had wallpaper, wouldn’t you wonder where the rest of the stuff is?

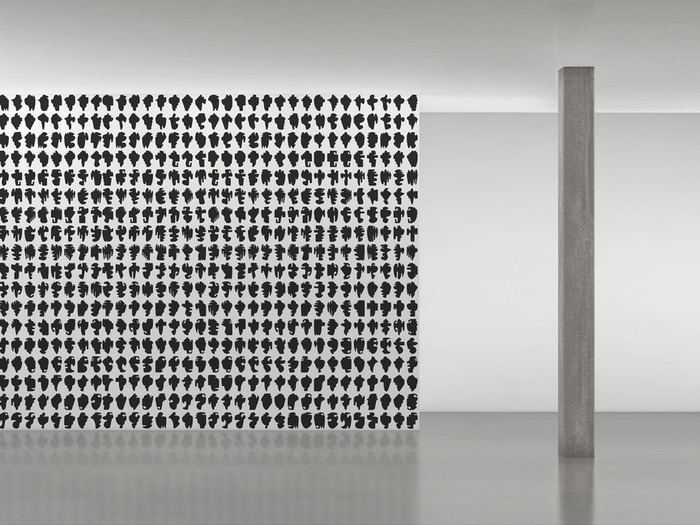

Allan McCollum’s The Shapes Project uses each of his 31 billion or whatever shapes only once, so each wallpaper installation will be technically unique.

Goldkicker is one of two Marilyn Minter wallpapers, and I think it’d really, really hold a room. Part of me wonders how hard it’d be to have art in a room with artist wallpaper, though.

Which is ironic. The degree with which an artist’s artwork can be replaced by a wallpaper version of it has some critical implications. Also, it might cut into his market. Or maybe the price points are just so different, it’s not an issue. Fred Tomaselli probably hopes so.

James Welling’s Glass House May, 2008, meanwhile, is similar enough to one of my favorite photomurals, the rare, surviving photomural that started it all [or at least my interest in photomurals]: a 1966 triptych of Mies van der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion.

Maybe artist wallpaper is closer to architecture than to art.

Maharam Digital Products [maharam.com]

1 [I realize I have seen at least one installation before: L&M Arts had Paul Noble’s wallpaper in its offices a while back. But maybe it wasn’t this one; it seemed more city than ruin.]

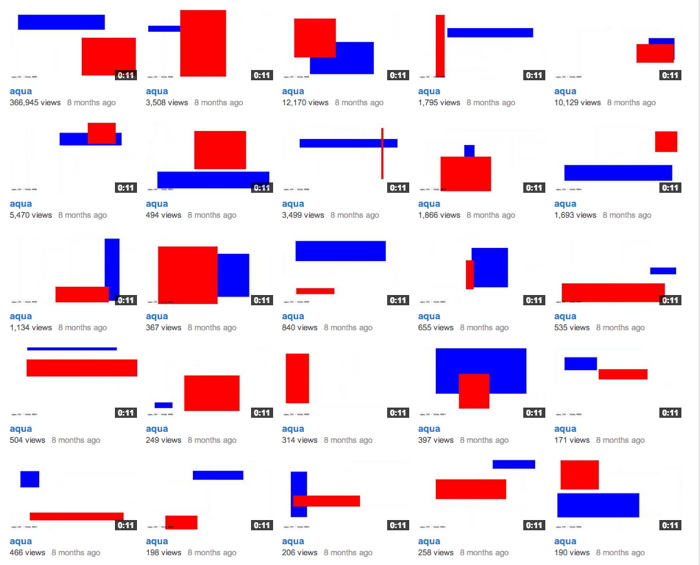

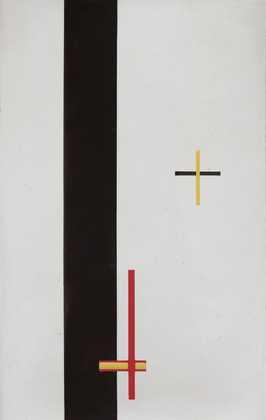

Webdriver Torso As Found Painting System

What you need is a system. To keep you going, to avoid artist’s block, to keep the pipeline filled.

I think Lewitt’s cubes were less a system than an idiom. Flavin’s fluorescent tubes, too.

Shapes from Maine, 2009, image: petzel.com

Allan McCollum’s got a few systems going. Systems are his medium. Define some parameters, calculate the total set, start producing, and don’t stop till you–or your market–drops. The Shapes Project, started in 2005, has 31 billion possible permutations, enough for everyone ever to be born on earth to have one. Personally, I’m largely unmoved by McCollum’s results, but I respect their jawdropping systemic integrity.

But On Kawara’s Today Series, now that’s a system I can get behind. It’s a bonus when your system is conceptually tight, also when it can carry you out of this world.

As that Kawara link above mentions, Hirst’s spots are also a system, which operates autonomously and, he’s even hinted, which could continue posthumously. [Kawara’s date paintings and Hirst’s spots were up in NYC at the same time in 2012, and Karen Rosenberg said one series was about time, and the other was about money. I love that.]

Anyway, you want to make sure you don’t get trapped by your system. Flavin had a helluva time with that, especially towards the end. So keep enough irons in the fire, throw a system or two into the merchandise mix. Like Richter’s new Strip paintings; he’ll be able to pull those off the printer till the very last. And he could leave the print queue open in his will, even. [I wish him all the continued health and happiness and look forward to seeing his show at the Beyeler.]

One would want a system to be ambitious, to stake a large claim, but to be doable, sustainable, saleable over the course of its realization. When Bruce High Quality Foundation announced their project to recreate all 17,000 objects in the Metropolitan Museum’s antiquities collection in Play-Doh, it seemed daunting. I guess you could say they’ll probably have product available as long as they’re able to keep selling.

Danh Vo, We The People, 2014 installation at Brooklyn Bridge Park, Public Art Fund, image: James Ewing

Danh Vo’s We The People project to recreate the Statue of Liberty as 250 separate panels, meanwhile, has a finite end, even though the ridiculously awesome scale of the project seems impossible. On a purely physical object level, this has to be one of my favorite art undertakings ever, a confluence of abstraction & representation, metaphor & literalism, presence & absence. As soon as I get to Vo’s pieces on view in City Hall Park and Brooklyn, I’ll try to write more about it.

From Kawara [solo] to Hirst [factory] to McCollum [vector files] and Richter [digital] we can see a diminishment of the artist’s hand in inverse proportion with the expansion in scope, approaching capitalist nirvana, an industrial-scale infinity.

This is all nice and terribly important, but it’s also prelude to what might be the most ambitious readymade art generation system ever, which I’m totally calling dibs on: Webdriver Torso.

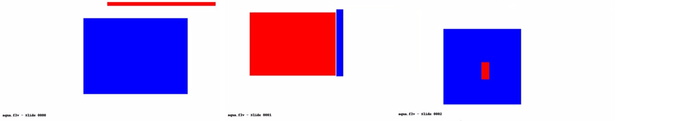

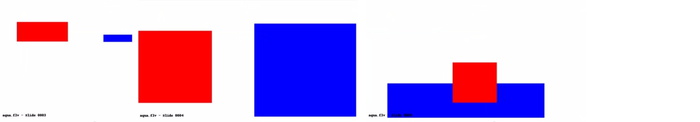

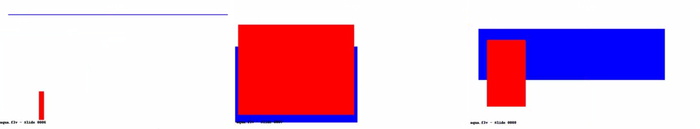

Webdriver Torso is the largest of at least four related YouTube accounts which have been uploading randomly generated videos [the pace is currently two videos ever 8-12 minutes] since mid-2013. Webdriver Torso has nearly 80,000 videos now; on all four accounts there are more than 130,000 videos total. Webdriver Torso’s channel now has more than 38,000 subscribers. Where a few weeks ago, almost all the videos had zero views, or maybe one, now videos of seemingly nothing immediately get several dozen views. [The other channels still have mostly zero views.]

Since being discovered and publicized a few months ago, various websites have speculated on the purpose and origin of Webdriver Torso, calling it an alien communications tool, or a crypto-spy numbers station, or a test channel for some video software developer. The most persuasive explanation I’ve seen so far is Italian blogger Paolo B.’s theory that the Webdriver channels are connected with a YouTube uploader development initiative for 3D videos or multiple videos, run out of Google’s Zurich office.

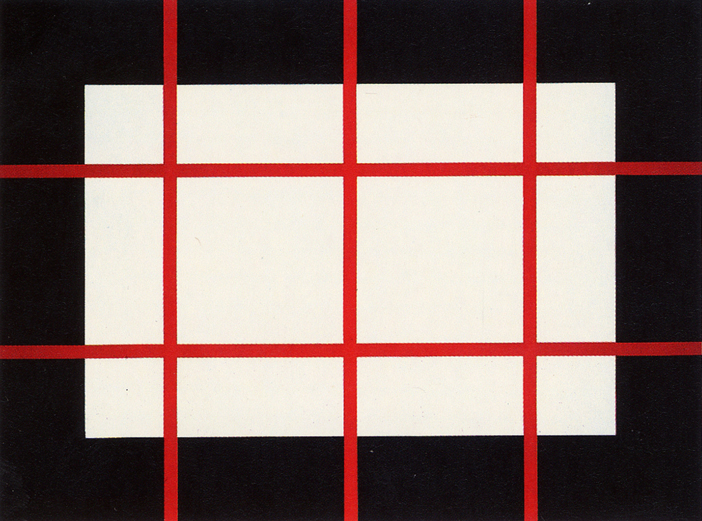

Each video is eleven seconds long and contains ten slides, each with a composition of blue and red quadrilaterals. That’s 1.3 million possible compositions, with more being added at an average rate of one every six seconds. And they all look more or less like a Malevich, or Lazslo Moholy-Nagy’s Telephone Paintings.

So obviously turn them into paintings. It seems impractical to sort through all the videos, looking for some “best” composition. Better to stay true to Webdriver Torso’s random nature, and grab a few. Or even grab one and use it [all], make nine paintings at a crack. Or maybe use the slides in the most recently uploaded file from the moment you make a sale, or the moment you place the order with Chinese Paint Mill. Then it becomes an indelible, but meaningless, marker, an index of its own creation. Like On Kawara’s date paintings, they can be made in various sizes. Maybe you get a giant hard edge monster to anchor an important wall. Or maybe you get a smaller, complete set and grid them up, a la Olafur.

A web storefront that offers paintings in only the compositions from the last few minutes of uploads wouldn’t just reward quick purchase decisions: it would demand it. Out with this fair-wandering nonsense of, “Oh put it on hold for me, I’ll let you know.” and in with Buy It Now. Of course, what’ll happen is that someone will sit there and hit refresh all day, in eternal hope that the next batch of nine will have the Webdriver Torso Mona Lisa in it. [Just a second, gotta check Twitter.]

Ooh, tmpK89znn, which just went up, has some really nice ones in it:

Let’s see how those turn out.

A timeline of Webdriver Torso [botpoet via @soulellis]

the truth about Webdriver Torso [ventunosu21]

Anxiety, Difference, The Limitations Of Resemblance

When this arrived last week, I immediately thought of something Sturtevant said in her short Frieze video last year, how due to cybernetics, “Simulacra was becoming minor in terms of its force.”

Also: “Repetition is not repeating. Repetition is like interior movement, It’s also difference, and it’s also pushing the limitations of resemblance.”

Because all those things feel very, very true right now.

Previously: Wade Guyton and Anxiety In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction

Riot Shields 2.0, Piratbyrån & Friends, Furtherfield Gallery

Furtherfield Gallery has opened an exhibition of art and archival material from Piratbyrån [Piracy Bureau], the Swedish art and activist group that became instrumental in the filesharing and access conflicts of the 00’s.

The exhibit includes a lot of material relating to the group’s trans-European bus tour pegged to Manifesta 07. My favorite things, though, are these “riot shields 2.0,” created by James Cauty. Even though Piratbyrån officially dissolved in 2010, these feel incredibly up-to-date right now. Unfortunately.

Piratbyrån and Friends runs through June 8 at Furtherfield in London [furtherfield.org, image via @Cybrsalon]

Piratbyrån and Friends album on furtherfield’s flickr [flickr]

UPDATE:

Here is a making of video from Cauty, showing the production of 1.0, the first edition of 30 Smiley Riot Shields. Apparently v0.9 was created in 2011 for Occupy St Paul’s. Actually, @jamescauty’s twitter feed has a step-by-step tutorial for making your own SRS, since the others are sold out. Very handy.

Previously, related:

Mar 2007: Million-Real Idea – advertising on Brazilian riot shields

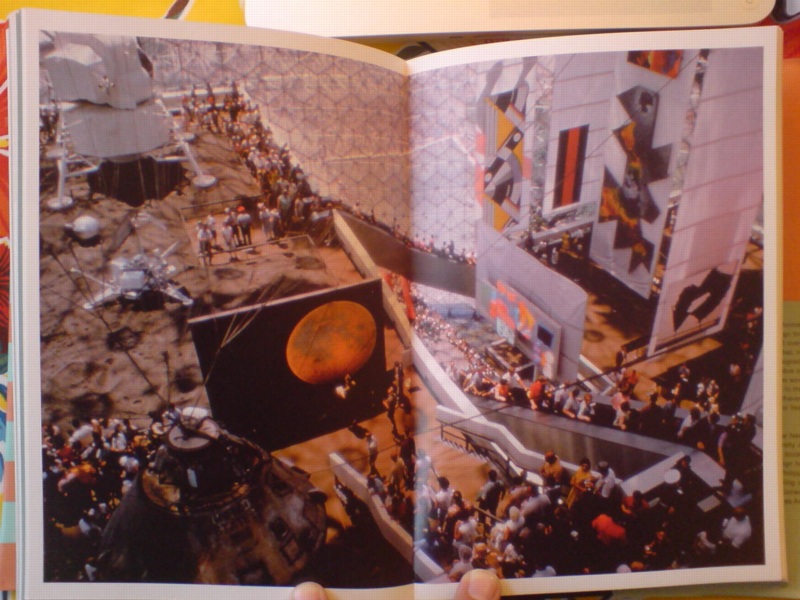

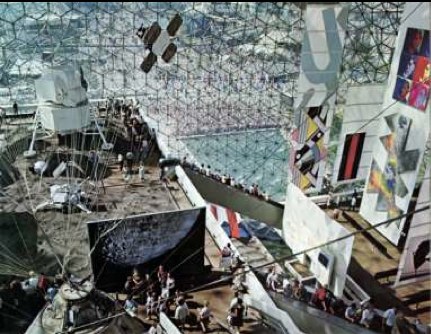

Pictures At An Exposition

One thing I noticed while researching Warhol’s World’s Fair commissions, is that the US Pavilion in Montreal had this sweet photomural of the moon.

both images by USIA’s Jack Masey

And it also had this sweet photomural of the moon. I can’t tell which came first or why.

Bogart, image via CHarstad

I think the way giant photos–of the moon and the stars alike–were used alongside giant paintings and giant graphics in the World’s Fair exhibition was one of the most advanced levelings of these supposedly distinct image hierarchies.

I’ve really got to get into the USIA Archives for this stuff. Actually what I need to do is get Jack Masey on the phone while I still can.

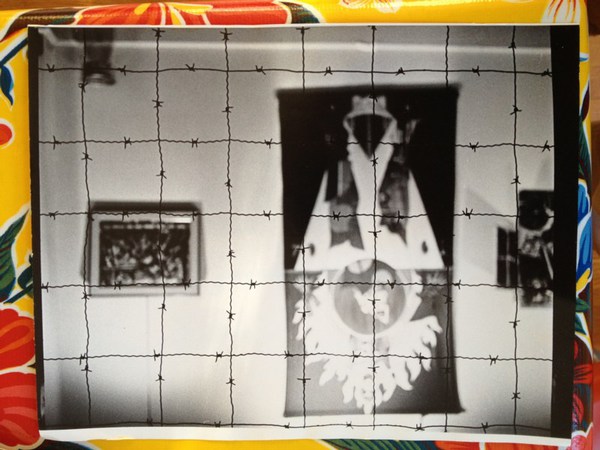

Donald Judd Was An Artist Against Torture

This Donald Judd woodcut caught my eye at Sotheby’s print sale this month, as much for its title as its contrast and complexity: Artists Against Torture, which, well.

It turns out Judd was one of 19 Artists Against Torture who were invited to make a fundraising print portfolio for the Association for the Prevention of Torture. I’m sure there are many more artists against torture, including, no doubt, many women, but for whatever reason, in 1992-3, the Geneva-based NGO commissioned these 19 men to make some art against torture.

So this Judd was a loosie from the portfolio. Which was published in an edition of 150, plus 40 APs, including one for each of the artists, not AP, ed. 40, as Sotheby’s sold it. Anyway it only sold for $3,750, a bargain for a Judd woodcut, so whoever bought it must have known something of the work. [The Judd Foundation sold their copy of the portfolio in that 2006 sale at Christie’s.]

The print reminds me a bit of Barnett Newman’s 1968 sculpture, Lace Curtain for Mayor Daley [above], in which a grid of barbed wire across a window frame protests Chicago’s police brutality against war protestors at the Democratic Convention. But for the similarity to be anything other than a coincidence, Judd would have to introduce representational content and metaphor into his work, which seems impossible. And yet that does look like bars on a cage, doesn’t it? If you let it?

Also I’m kind of interested by Judd’s political involvement. I wouldn’t have expected that, even though I know he was directly involved in mobilizing to protect SoHo. Turns out the Judd Foundation had a show in Marfa in 2011, “The Public Life,” about the artist’s political, social, and environmental activities.

1 May 2014 | Lot 225, Donald Judd, Artists Against Torture (sic), sold for $3,750 [sotheby’s]

APT’s Artists Against Torture portfolio was exhibited at the Ritter Museum in 2012. [museum-ritter.de]

So Different, Yet So Alike

I know it’s folly to take auction catalogue text as art history, but it is of a piece, at least in this case.

Untitled, recto, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, image: Sotheby’s

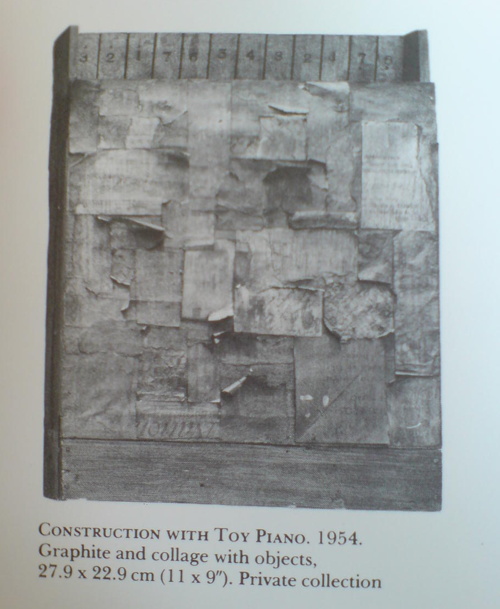

Last night’s sale at Sotheby’s included a very early, underdocumented 1954 combine by Robert Rauschenberg, which he gave to the dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor a decade later. [I say underdocumented because I can’t find any mention of it in Paul Schimmel’s otherwise exhaustive Combines catalogue, or anywhere online not associated with the auction.]

Untitled, verso, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, that polka dot fabric turns up on at least six other combines, including Short Circuit, image: Sotheby’s

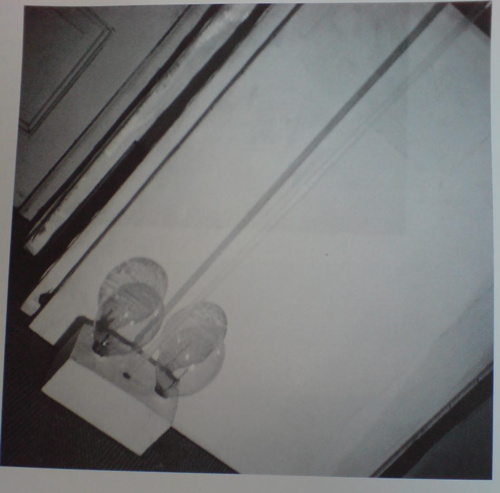

The piece is freestanding, tabletop-size, with a double-sided painting/collage mounted on what seems like a 2×4 wood base. There’s a lightbulb sandwiched in between the support slats, and a pair of radiometers, those little gadgets with black & white panels that spin when exposed to light.

The Man With Two Souls, 1950, photographed by Rauschenberg in 1951 in his UWS apartment, where Twombly told Walter Hopps he’d seen it. He later got it. image: Hopps’s Rauschenberg: The Early 50s

As soon as I saw it, I thought of Rauschenberg’s earliest surviving sculpture, made in 1950. Cy Twombly got it after Rauschenberg’s 1951 show at Betty Parsons, but before he and Bob took off for seven months to Africa, leaving Susan Weil and the baby behind. The piece is called The Man With Two Souls, and it consists of a glass rod flanked by a bulbous pair of wine bottles inserted in a cast plaster block. Charles Stuckey suggested it was an homage to Barnett Newman’s sculpture Here I, which was shown at Parsons earlier in 1951. Yes, that might be one allusion.

Twombly and sculptures in Twombly’s studio, 1954, photographed by Rauschenberg, image via Schimmel’s Combines

It also might be similar to almost every Cy Twombly sculpture in these photos Bob took in 1954, the year Taylor’s combine was made. The year, in fact, when Rauschenberg made what’s considered the first of his combines, set pieces for Taylor’s debut as a choreographer after leaving Merce Cunningham’s company in mid-1954.

And depending on which side you’re looking at, Taylor’s piece looks an awful lot like Minutiae, the free-standing set piece Bob made for Merce’s December 1954 performance at BAM. Which is all set up for my complaint about Sotheby’s catalogue text, which acknowledges that Rauschenberg was “informed by the influences” of his contemporaries like Jasper Johns, and then immediately distances the two artists:

Though their practices were fundamentally at odds, both conceptually and aesthetically, the two men supported each other’s stylistic experimentation during this critical time of immense growth and evolution.

Unfathomable difference has been the starting point of any discussion of Rauschenberg and Johns’ early work since at least 1963, when Allan Solomon gave them each one-man shows at the Jewish Museum. It’s a presumption of separateness that shuts off any exploration of similarity, much less exchange or collaboration. And especially in the case of Rauschenberg and his artist/partners, it heads off any questions of joint creation or shared authorship.

Minutiae, made with help from Johns in time for Merce Cunningham’s Dec. 7 1954 performance at BAM

Johns has said publicly he worked on Minutiae. Twombly drew on Rebus and who knows what else. Johns even said he made a Rauschenberg with Bob later signed, and that he came up with the term “combine.”

But whether it’s historic or persistent institutionalized homophobia, emotions & ego, the demands of the market, or the lone genius paradigm of the times, it’s apparently still impossible to ask if there are similarities or connections between these artists’ contemporaneous work.

Construction with Toy Piano, 1954, image: Michael Crichton’s Jasper Johns

Twombly and Rauschenberg are both gone, alas, and Johns doesn’t seem too interested to elaborate, seeing as how he has systematically hunted down and destroyed his own work from before 1955. But at least one piece that survives, Construction with Toy Piano, a book-sized wooden object covered with painted collage, looks like it could have been made in the same room as Paul Taylor’s combine, if not by the same mind or hands. Just asking the question.

‘I’m Going To Fail’, or Protocols of Participation

I like to keep up with the discussions and presentations at NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts. They recently posted video of a panel I’d been waiting for from late April titled, “Protocols of Participation: Recent Models of Socially Engaged Art in the United States and Europe,” where Creative Time’s Laura Raicovich, and Xavier Douroux and Thérèse Legierse from Nouveaux Commanditaires, who commission and mediate public artist projects in France. IFA’s own professors Thomas Crow and Alexander Nagel participated as well. [It was organized as part of ART², a whole month’s worth of events I missed across the city.]

It was an interesting comparison of the two systems designed to facilitate artists’ engagement in their politics, culture, and communities. So watch the whole thing.

I had it playing in the background while I worked, and during the audience questions, I was suddenly alerted to the change in cadence. I knew what was coming: the long, winding, potentially discourse-derailing statement disguised as a question.

It’s a cliche of the panel discussion/public lecture format, the kind of interaction that organizers sometimes like to head off by explicitly warning against, or even by soliciting written questions. It’s almost always an uncomfortable, flow-breaking moment, met with either indulgence or annoyance. No one’s come to hear some rando bounce his pet theory off the headliners.

It breaks form, yet it is the form. Such questions and their possibility are intrinsic to the very format of open, public discourse. So when the breach of protocol came for an event titled, of all things, “Protocols of Participation,” I resisted the urge to close tab or tune out. And I was transfixed by this unseen, unidentified woman’s speech, how she said it, and even what she said. It occurred to me that probably no one would ever take her comment seriously, or even know about it.

[I vividly remember my first audience question in New York City. It was to Brice Marden at MoMA’s Cy Twombly artist panel. Years later, when WPS1 posted the audio of the event, it omitted the audience Q&A segment entirely. Which can be interpreted on several levels.]

In every panel or discussion I attend, I, like everyone else, always fantasize about revolutionizing the format. Or at least fixing it. It never feels optimal. And yet it never, ever changes. So I’m going to start collecting these marginalized, random, dodged, cut-off, derailing statement/questions from audience members and see what comes of it. Do you have a favorite? Send a link, let’s add it to the collection!

As you can see from the complete transcript of the audience member [with a couple of interjections and a response by Prof. Nagel], maybe these things should be written down and studied after all. Because as a text, I think it’s rather fascinating. Expectations and context.

Watch/listen to the question, beginning around 1:27:10. I wanted to capture the sense of hearing it, so I left in the ums and repetitions. Line breaks are pauses.

I’m going to fail

um I missed a little bit, but I was misdirected to the wrong place, sorry

um

Continue reading “‘I’m Going To Fail’, or Protocols of Participation”