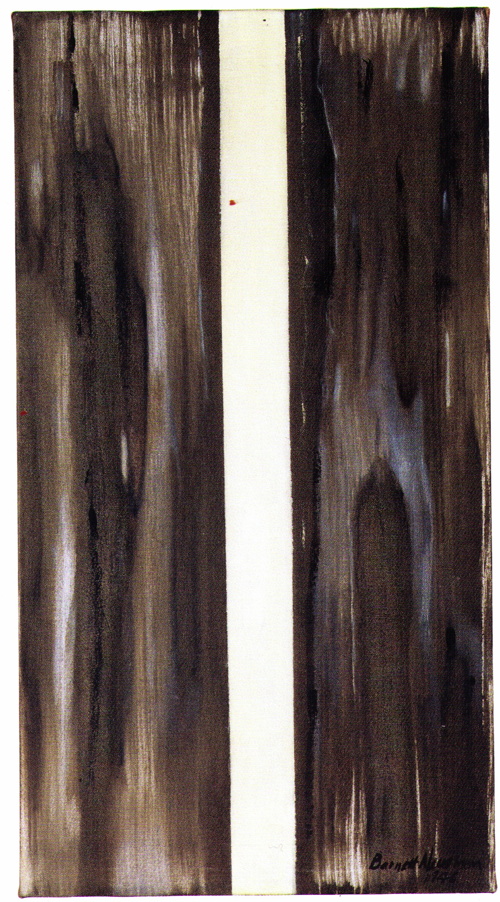

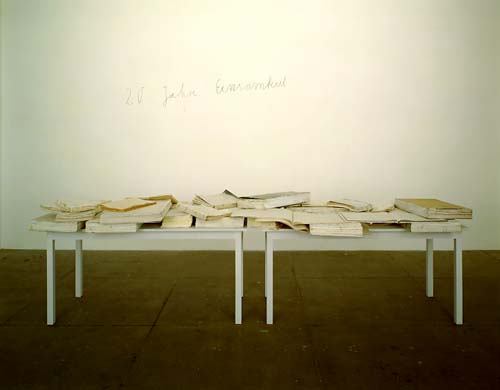

Felix Gonzalez-Torres actually made a lot of paintings. Most are Bloodworks paintings, gesso and graphite grids bisected by a diagonal line, referring to a doomed medical readout.

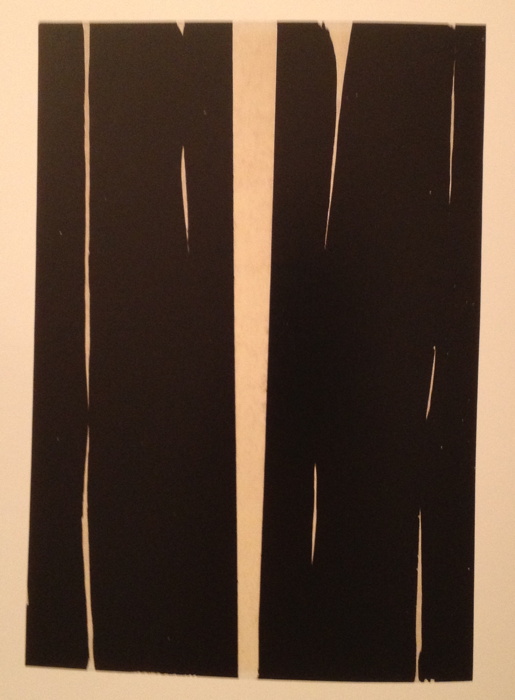

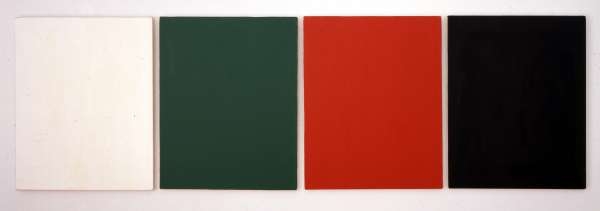

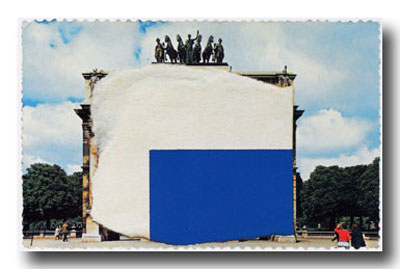

But in 1988 he also made Forbidden Colors, four 16×20-in acrylic monochromes in white, green, red and black. He showed the piece, along with four framed photostats, in a project installation at The New Museum, 25 years ago right now.

The paintings are now owned by MOCA. The text Felix wrote for the show is below [reproduced in Julie Ault’s 2008 Felix monograph, via fernandocestari]:

INSTALLATION BY FÉLIX GONZÁLEZ-TORRES September 16 – November 20, 1988

When I was asked to write a short statement about the work in this space I thought it would be a good opportunity to disclose and, in a certain sense, to demystify my approach. I hope that it will guide the viewer and will allow an active participation in the unravelling of the meaning and the purpose of this work. Many may consider this text redundant; and unnecessary intrusion, or even a handicap. It is assumed that the work must “speak for itself,” as if the divine dogma of modernism were able to deliver a clear and universal message to a uniform “family of man.” Others know this is not true that each of us perceives things according to who and how we are at particular junctures, whose terms are always shifting. Preferably the exhibition gallery will function as an educational device, simple and basic, without the mysteries of the muse, reactivating history to affirm our place in this landscape of 1988.

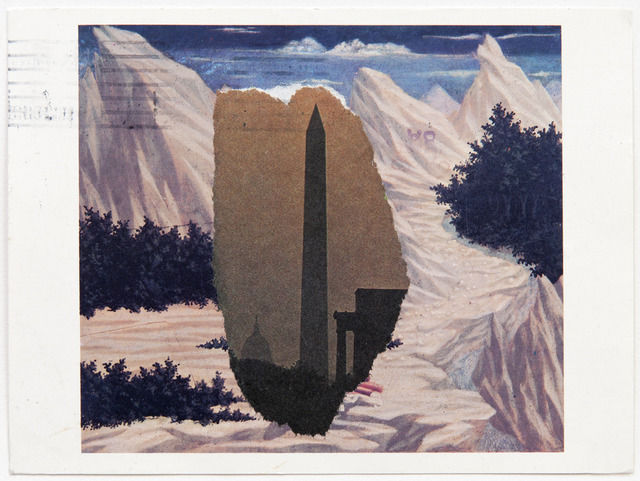

This work is mostly personal. It is about those very early hours in the morning, while still half asleep, when I tend to visualize information, to see panoramas in which the fictional, the important, the banal, and the historical are collapsed into a single caption. Leaving me anxious and responsible to anchor a logical accompanying image scanning the TV channels trying to sort out and match sound and sight. This work is about my exclusion from the circle of power where social and cultural values are elaborated and about my rejection of the imposed and established order.

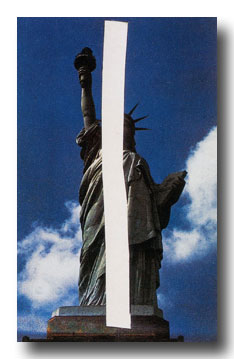

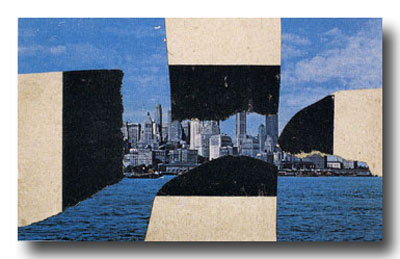

It is a fact people are discriminated against for being HIV positive. It is a fact the majority of the Nazi industrialists retained their wealth after war. It is a fact the night belongs to Michelob and Coke is real. It is a fact the color of your skin matters. It is a fact Crazy Eddie’s prices are insane. It is a fact that four colors red, black, green and white placed next to each other in any form are strictly forbidden by the Israeli army in the occupied Palestinian territories. This color combination can cause an arrest, a beating, a curfew, a shooting, or a news photograph. Yet it is a fact that these forbidden colors, presented as a solitary act of consciousness here in SoHo, will not precipitate a similar reaction.

From the first moment of encounter, the four colour canvases in this room will “speak” to everyone. Some will define them as an exercise in color theory, or some sort of abstraction. Some as four boring rectangular canvases hanging on the wall. Now that you’ve read this text, I hope for a different message.

For all the PWAs.

I don’t think I’ve ever seen Forbidden Colors in person. It was in a group show at White Columns in 1993, and MOCA showed it once in 2002. That’s it. I’ve noticed it in the catalogue raisonne, of course, though without really paying the piece much attention. Really, I didn’t understand the reference. And the photo didn’t really reproduce the green panel; it looked black.

UPDATE Thanks to petitemaoiste, who just tweeted that the piece was also included in John Farmer’s 1995 collection show, “The Compulsion to Repeat.”

It’s interesting, though, how you notice things, or take notice of them, when your own frame of reference changes.

The ban on the Palestinian flag, its colors, and any “artwork of ‘political significance'” was lifted in 1993 as part of the Oslo Peace Accords.

[December 2023 UPDATE: In 2021 in response to Israeli violence against Palestinians, I made a replicable version, Gonzalez-Torres’ Forbidden Colors, and offered it to any institution who wanted to show but could not borrow the original. Also, the original was included in the 2023 Carnegie International. Meanwhile, it is a new fact that Israel, Germany, the UK, and places in the US, among others, are actually banning display of the colors of the Palestinian flag, part of an attempt to silence protest of the ongoing genocide in Gaza and attacks in the occupied West Bank.]

What would assembling a more complicated or randomized chain of Wikipedia links yield? Is there a Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon-like connectedness between any and all bits of human knowledge [on Wikipedia]? Is there poetry or literature to be found/made there? Could an algorithm surfing through Wikipedia produce meaning or newness, or something beyond the temporary frisson of WTF juxtaposition?

What would assembling a more complicated or randomized chain of Wikipedia links yield? Is there a Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon-like connectedness between any and all bits of human knowledge [on Wikipedia]? Is there poetry or literature to be found/made there? Could an algorithm surfing through Wikipedia produce meaning or newness, or something beyond the temporary frisson of WTF juxtaposition?