An exhibition of Andreas Gursky photos opened at the National Art Center on July 3rd, the day after I arrived in Tokyo. My first instinct was to not go, because of the whole Ghetto Gursky thing, but I decided that, precisely because I’m making some of my own now, I really should see the Gursky Gurskys again up close. It was highly enlightening.

I would not call the show a retrospective. There were three curators involved from two Japanese institutions, but the 65 photos were “specially selected by Gursky himself.” In fact, except for a lone Pyongyang photo which is in the collection of the other venue for the show, the National Art Museum, Osaka, all the works come from the artist’s own collection. [The selection looks very similar to to the Museum Kunstapalast show last year.] Another similarity: instead of a chronological approach, the show organizers explain, Gursky designed the exhibition to “uniquely aim to show the entire body of work as a single unified entity with both old and new and small and large formats displayed side by side.”

Which, wait, what? Small format Gursky? Is that some kind of Zen koan? Above all else, a Gursky is known for its “panoramic scale”; a “huge scale that envelops our body”; a “huge picture” with “a powerful presence…as an object,” which requires an “active viewing experience,” moving out and in, similar to that commonly used for large paintings. These descriptions all come from the current show’s catalogue essays, but they’re identical to nearly everything that’s been written about Gursky’s photographs since the 1990s. They’re bleeding edge big, and they’ve only been getting bigger.

Gursky NACT installation shot showing small prints, taken by gadabout.jp, which also has a great photo of the artist

And yet fully a quarter of the prints in this exhibition, including some of his most well-known images, are small, around 40×50, 60, or 70cm. That includes Rhine II [whose$4.3 million auction result is mentioned in the show’s introduction]. It’s a dry-mounted inkjet print measuring just 43x71cm. That’s even smaller than the exhibition poster.

Exhibition poster for NACT’s “Gursky” depicting Rhine II, size A1, signed ed. of 200, 58,000 yen.

How often were such editions made or shown? Only your dealer knows for sure. I admit, it wasn’t until Rhine II sold in 2011 that I realized Gursky made an image in sizes other than “absolutely biggest possible.” From the part of Christie’s catalogue notes not cribbed from Tate: “Unusually for the artist, this series contains photographs produced on multiple scales, the present work being the largest of the entire edition.” But that meant 2×3.5m [like at Tate and Christie’s], and 1.5x3m, [like at MoMA and the Pinakothek Moderne, Munich]. Now there’s a 40x70cm pocket size, too? And what to do about that poster, which is available as a signed edition of 200, for 58,000 yen, in the exhibition site’s Gursky “Goods” section? Yes. アンドレアス・グッズキー。

Centre George Pompidou, 1995, image: tate

It’s not like there’s never been any. There’s everyone’s My First Gursky, of course, the Pompidou image (54x70cm) he released as a Parkett edition of 60+?? in 1995. [Ironically, the image above is of one of two large-scale artist proofs of the image, which was a gift to Tate Modern from architects Herzog & deMeuron, whose exhibition is depicted.]

And in a show at White Cube in 2003, Gursky did include an adorable little diptych of 99 Cent. Actually, those wide borders kind of kill it for me.

OK, jump back. Here’s the Gursky page at the local Cologne auction house Van Ham, which has more than a dozen small images, published in editions of 12-30, including even a couple of offset prints.

So the three Bangkok series prints, in editions of 50 each, being sold by lottery at the gift shop for 500,000 yen, have context after all.

Since seeing the show until I sat down to research and write this out, I had assumed that with these little prints, I’d been beaten to the Ghetto Gursky punch by the artist himself. But these are not Ghetto Gurskys; they’re Entry Level Gurskys. Totally different. And those early German ones? Emerging Artist Gurskys. Also totally different.

Anyway, back to the show. These small prints did not really work for me. They primarily serve, along with the non-chronological hanging, to obscure the evolutionary relationship between Gursky and his technology, namely large-format photo printing and Photoshop.

There are definitely transition points and leaps to be seen between prints of different eras, in terms of size, medium, and resolution. And though two of the three curators emphasize the objecthood of Gursky’s photos, these actual characteristics, the print equivalent of a painting’s facture, go completely unmentioned.

One thing that jumped out at me: 1996-7 seems like it was a rough period for C-prints. Up close, a couple of those Prada shelf images looked like Seurats. But by 1999 they got better. The massive Ocean prints (2010), which were worked up from satellite imagery to look like animated airline inflight video maps, are giant C-prints of quality. But the Bangkok series (2011) of manipulated, river reflections, are crispy inkjets, perhaps another process shift.

All the small photos are inkjets, too, even the Parkett edition that was originally a C-print. A very early photo, Ruhr Valley (1989), is seen as a C-print 2.2x3m C-print, a scale I don’t believe was possible when the image was made. Indeed, it used to be dated 1993, which is presumably when the 57×66-inch version was produced. Which means Gursky’s objects are actually photographs after all. He goes back and prints them again. Size matters, but not as an indication of age. Emulsion grain and chemistry matter, but not as an indication of patina. I’ve heard Gursky will offer collectors reprints when images have destabilized or faded. Which is probably good customer service. But which seems rough on the object/painting positioning. In any case, no one in Japan, at least, cares when anything was printed.

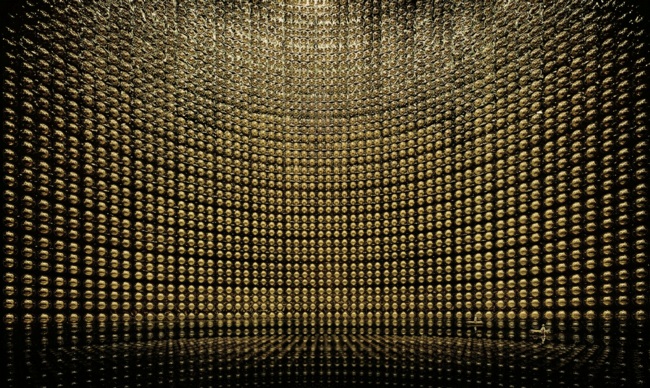

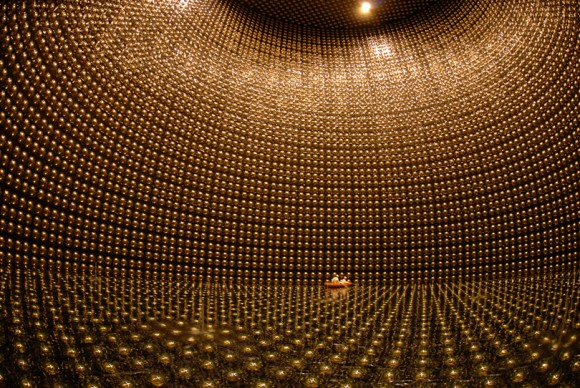

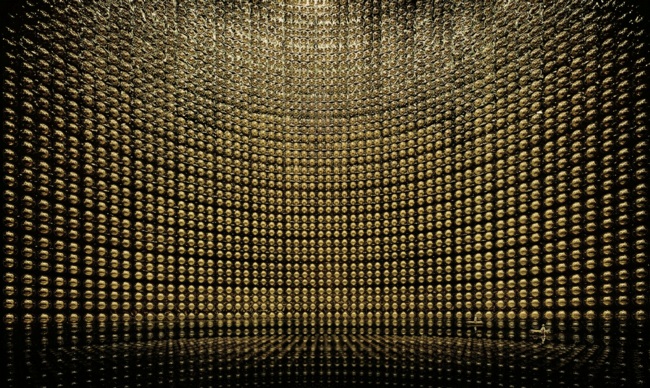

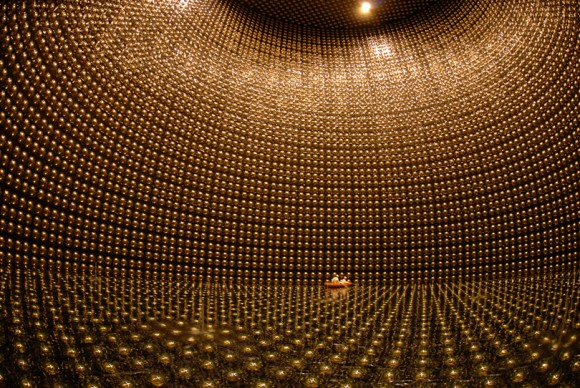

Gursky’s Kamiokande, 2007, image via: whitecube

Something else that really complicated my view of Gursky’s works was evident from the signature image for the show: Kamiokande (2007). It’s a photo of the Super Kamiokande neutrino detector which, coincidentally, I’d tried to visit on this trip. [We spent time nearby, in the mountains of Gifu prefecture.] It’s also something I have written about here before. And so it’s extremely obvious to me that Gursky’s image, in aspects large and small, is nearly identical to earlier published images of the giant underground tank.

Image from 2001 or whenever, from Super-K themselves

Indeed, in the catalogue’s obligatory, “But what does Gursky think about Japan?” essay, curator Yuka Uematsu writes:

After seeing pictures of the facility in a magazine, Gursky chose the site as a motif for his work. At the time he shot the picture, the water had been drained to repair a damaged photoelectric tube, so he used a digital editing technique to add the water’s surface, which reflects the image and the workers riding in two boats.

Gursky’s well known to use digital manipulations and alterations to transform his images from depictions of reality to embodiments of his own Gursky Vision. “A restructured image” seen, as curator Mitsue Nagaya puts it, “through the filter of Gursky’s eye.” It’s just that sometimes, that eye looks at someone else’s photograph.

Gursky’s work, writes Nagaya, “presents a new vision of the relationship between people and the world.” He reveals and revels in the awesome scale of globalized capital. In 2001, when he had his MoMA show, people wrote of Gursky’s “zeitgeist images.” The artist himself called them “icons of our time.” Peter Galassi’s essay for that show was titled, “Gursky’s World.” But Gursky is not (or not just) looking at the world; he’s looking at images of the world. Images in the world. And that seems like a significant, and under-recognized difference.

It began in 1990, we’re told, when he saw a photo of the Tokyo Stock Exchange in a newspaper and decided to shoot one like it himself during a visit for a group show. Gursky started scouring the media with his GurskyVision. When he found an awesome image, a spectacle that captured man’s dehumanity to man, his puniness in the face of the vast systems he’s built, he’d set out to have his own Gursky Moment, by photographing it. By rephotographing it. And when the reality he photographed didn’t approach the image in his eye, or in his head, or in his scrapbook, he’d invoke artistic license to alter it. The result is not an idealized, aestheticized version of the world, but of the mediated representation of it.

Gursky NACT exhibit ad on Tokyo Metro platform, photographed by ysmn1120

Which may be why my favorite images from Gursky’s Tokyo show are not in the gallery at all. User ysmn1120 shot this Instagram of an ad featuring 99 Cent on a Tokyo subway platform. [Tonotype snapped it too.] It’s spectacular. Exactly where it belongs and for what it is. It is the Ghettoest Gursky of all, and I am bummed I didn’t think of it, that couldn’t find it, and that I don’t have one.

I did find a sweet, domestic-sized lightbox version of Kamiokande at Roppongi, though. It’s a nice nod to Jeff Wall, who exerted an early, formative influence on Gursky’s push into large-format.

OK, this is sweet. Gursky’s show last year at Gagosian Hong Kong had even bigger billboards, which are included in the gallery’s installation shots. [There were also several little editions. They really are the perfect synthesis of collectibility and pointlessness.]

Meanwhile, the Ghetto Gursky project turns out to be much closer to Gursky’s own practice than I initially realized. The only difference being that the imageworld I’m picking from has Gurskys in it, too.