Joseph H. Choate, a civic-minded attorney and member of the Provisional Committee which, under William Cullen Bryant, undertook the creation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, spoke for the Trustees at the dedication of the Museum’s first building on March 30, 1880.

Joseph H. Choate, a civic-minded attorney and member of the Provisional Committee which, under William Cullen Bryant, undertook the creation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, spoke for the Trustees at the dedication of the Museum’s first building on March 30, 1880.

There are many quotes in circulation since then, which variously generate feelings of awesome prescience, inspiration, bemusement, and Bizzaro world dissonance. But so far Mr. Choate’s speech appears not to have been published in its entirety, at least in any form that has reached the web. The most complete version I can find is from the June 1917 Bulletin of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, in memory of Choate’s passing and his decades-long service to the Museum.

Here are the full paragraphs around a couple of oft-used quotes [in bold], which I’ve broken up because, hoy, who reads paragraphs that long online?

The erection of this building at the expense of the public treasury for the uses of an art museum was an act of signal forethought and wisdom on the part of the Legislature. A few reluctant taxpayers have grumbled at it as beyond the legitimate objects of government, and if art were still, as it once was, the mere plaything of courts and palaces, ministering to the pride and the luxury of the rich and the voluptuous there might be some force in the objection.

But now that art belongs to the people, and has become their best resource and most efficient educator, if it be within the real objects of government to promote the general welfare, to make education practical, to foster commerce, to instruct and encourage the trades, and to enable the industries of our people to keep pace with instead of falling hopelessly behind those of other States and other Nations, then no expenditure could be more wise, more profitable, more truly republican.

It is this same old fashioned and exploded idea, which regards all that relates to art as the idle pastime of the favored few, and not, as it really is, as the vital and practical interest of the working millions, that has so long retarded its progress among us.

…

Let me briefly state to you their [the trustees’] purposes. They believed that that the diffusion of a knowledge of art in its higher forms of beauty would tend directly to humanize, to educate and refine a practical and laborious people; that through the great masterpieces of painting and sculpture which have commanded the reverence and admiration of mankind, and satisfied the yearnings of the human mind for perfection in form and color, which have served for the delight and the refinement of educated men and women in all countries, and inspired and kept alive the genius of successive ages, could never be within their reach, yet it might be possible in the progress of time to gather a collection of works of merit, which should impart some knowledge of art and its history to a people who were yet to take almost their first lessons int hat department of knowledge.

Their plan was not to establish a mere cabinet of curiosities which should serve to kill time for the idle, but gradually to gather together a more or less complete collection of objects illustrative of the history of art in all its branches, from the earliest beginnings to the present time, which should serve not only for the instruction and entertainment of the people, but also show to the students and artisans of every branch of industry, in the high and acknowledged standards of form and color, what the past has accomplished for them to imitate and excel.

But the 1917 memorial version curiously leaves out what may be the best part: The Ask.

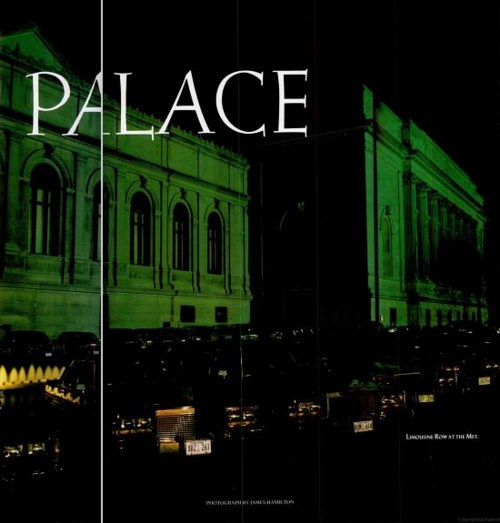

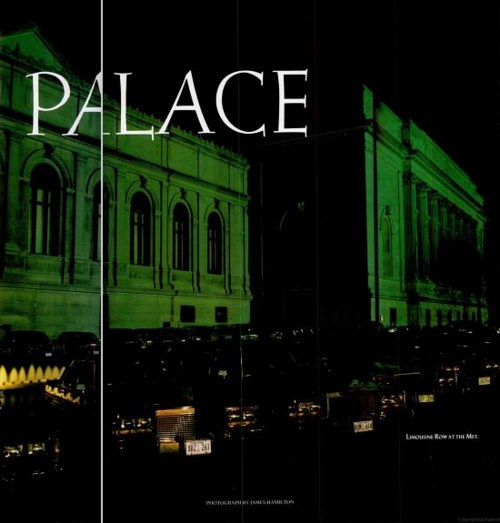

“Limousine Row at the Met”, image via nymag

Near as I can tell, the Met’s founding fundraising pitch first resurfaced in Calvin Tomkins’ 1970 history of the museum, Merchants and Masterpieces, and then again in 1989, at the zenith/nadir of the museum’s “Club Met” private party rental era, asbreathlessly, chronicled in New York Magazine by John Taylor. It really is awesome, and should be carved in stone on the Grand Staircase:

Think of it, ye millionaires of many markets–what glory may yet be yours, if you only listen to our advice, to convert pork into porcelain, grain and produce in to priceless pottery, the rude ore of commerce into sculptured marble, and railroad shares and mining stocks–things which perish without the using, and which in the next financial panic shall surely shrivel like parched scrolls–into the glorified canvas of the world’s masters, that shall adorn these walls for centuries. The race of Wall Street is to hunt the philosopher’s stone, to convert all baser things into gold, which is but dross; but ours is the higher ambition to convert your useless gold into things of living beauty that shall be a joy to a whole people for a thousand years.

Joseph H. Choate, a civic-minded attorney and member of the Provisional Committee which, under William Cullen Bryant, undertook the creation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, spoke for the Trustees at the dedication of the Museum’s first building on March 30, 1880.

Joseph H. Choate, a civic-minded attorney and member of the Provisional Committee which, under William Cullen Bryant, undertook the creation of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, spoke for the Trustees at the dedication of the Museum’s first building on March 30, 1880.