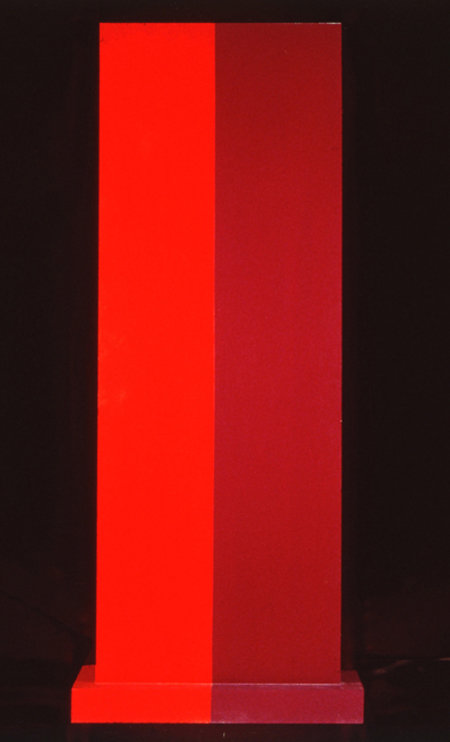

Insurrection, 1962, image: corcoran.org

I needed to see some hard-to-find Chris Burden catalogues–more on that later, but soon–and the quickest place I could find them was the Corcoran School’s library. I called ahead, and they had them waiting for me, so I was in and out of the library in no time.

Which left me with a little time to wander. And there is a very nice gallery with a nice, old Ellsworth Kelly diptych, and this wonderful Anne Truitt sculpture in the center of the room.

Insurrection was installed very dramatically with Hardcastle, another 1962 work, in Kristen Hileman’s Truitt retrospective at the Hirshhorn. Hardcastle confronted you head-on through the doorway, while Insurrection was turned sideways; on edge, with only the slab’s thinness and wooden brackets visible. It was only as you moved around it–following the contours of those unfortunate Karim Rashidian raised platforms–that they switched out: Hardcastle’s heft gave way, and Insurrection widened, revealing that they shared the same structure.

Hardcastle, 1962, via annetruitt.org

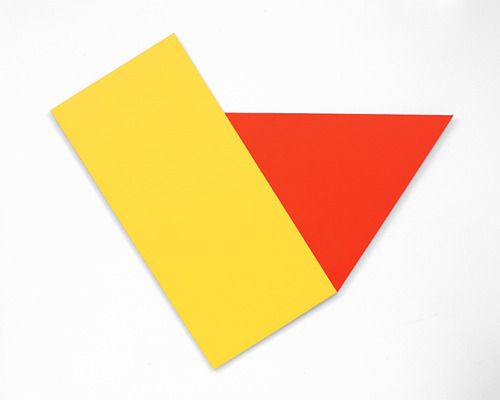

The install of Insurrection at the Corcoran, meanwhile, is much less enigmatic. There are off-center approaches from three different sides, so the sculpture is what it is when you see it. Moving around it is an experience, not a discovery. [The full frontal orientation faces the Kelly, Yellow with Red Triangle, from 1973.]

Yellow with Red Triangle, 1973, image corcoran.org

Even though they’re the same shape/structure, I remember Hardcastle‘s monochrome face felt more massive–and then artificial, as its red brackets popped into view. Insurrection’s two-tone reds make it feel more like two volumes immediately, which turn out to be one.

Back down on the floor where they belong, Truitt’s larger sculptures always feel like a presence, in space, and yet they’re paint[ings?] [ed?] And yet there is paint. Maybe 1962 was before her reportedly vigorous sanding and multiple coats kicked in, because Truitt’s surface is most definitely painted with a brush. Kelly’s surface, meanwhile, is only disturbed by the weave of his canvas; I’m going to assume he used a roller. But wow, there’s a brush going around the edges. And how. Just slapped right on there.

I’m trying to better understand the sense of paintings as objects, of the picture plane as nothing of the sort. I didn’t plan today to see these two artists’ works–Truitt’s and Kelly’s–which explore this very idea, in the form of painting/sculpture, but here they were. I still have to look some more, but basically, I came away thinking I might be really knocking myself out too much over my smoothly brushed-on painting surfaces.

previously: many Anne Truitt posts on greg.org

and a little on looking at Ellsworth Kelly

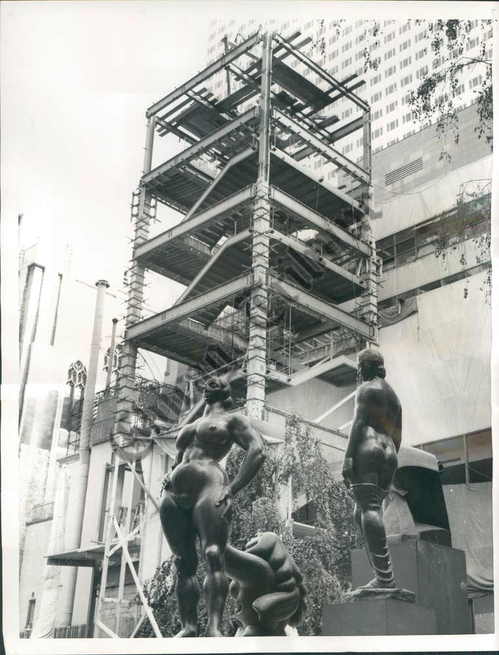

MoMA Sculpture Garden Fire Escape

You’d think I’d learn the importance of clearing browser tabs by now. I’ve had this eBay listing open for a couple of weeks now, thinking I’d buy it. And then last night I decided to pull the trigger. And then to just do it in the morning. And it was gone.

It’s a rather awesome press photo from September 1958 of a temporary staircase erected in the Museum of Modern Art’s Sculpture Garden after the fire that destroyed a couple of Monet’s Water Lilies paintings.

The Tribune Company was selling the print, liquidating the photo morgues of various of its venerable newspapers at $15 a pop, while stamping its watermark across the digital version “to deter image theft [sic].” Mhmm.

This kind of provisory structure, something more than a scaffold but less than an actual building, is awesome to me. It’s a type of architecture that doesn’t often get documented, much less studied, and almost never preserved. The related exception, though, are 19th century Army-issue observation towers at Gettysburg, but even those seem to have been designed, not just built.

Previously: MoMA on Fire

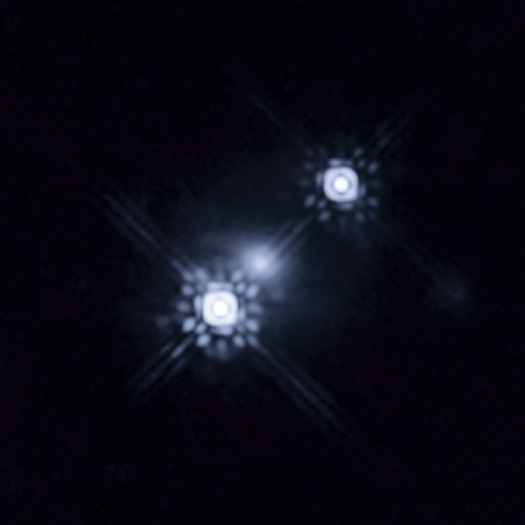

Intergalactic Lens Flares

i love that the headline on this story, “Hubble Directly Observes The Disk Around A Black Hole,” has to be followed immediately by, “but it’s not that disk.”

The spectacular patterns and rays in the photo above of the double quasar known as HE 1104-1805 are apparently imaging artifacts from the Hubble Space Telescope, They’re caused by the circular aperture and the structural elements of the telescope itself.

Meanwhile, the accretion disk is only visible at all because HE 1104-1805 is subject to gravitational lensing, distortions in the light caused by the gravitational pull of an intervening galaxy.

I can’t quite articulate it yet, but there’s something here about the appeal and limits of opticality; the utility and limitations of the narrow, visible part of the spectrum; and the documentation and characterization of distortion that I find very interesting. And then there’s the inextricable relationship between the instrument and its object; which then collapses as the universe itself–the galaxy-as-lens–becomes the instrument for viewing itself.

Hubble Directly Observes the Disc Around a Black Hole [spacetelescope.org, via]

What’s That Strange Disk Around That Black Hole? [discovery.com]

Good Thing I Didn’t Go To Art School

Jerry Saltz tells Artinfo a few of his least-favorite art world things, including:

an endless stream of art-school-trained artists trying to crawl up the asses of Andy Warhol, Richard Prince, and Gerhard Richter in order to stake out a microscopic piece of insular, already-approved territory

Oh yeah, I hate those guys, too!

19 Questions for Jerry Saltz [artinfo]

‘The Gate’ By BHQF, Curated At Sotheby’s By Vito Schnabel

In 2005, designer Ian Adelman and his colleagues spotted The Gate chasing Robert Smithson’s posthumously realized Floating Island. Adelman snapped a photo, which ended up on the front page of the New York Times. It was only revealed some years later, after several arch, art world stunts established their reputation, that the pseudonymous collective Bruce High Quality Foundation acknowledged The Gate had been their inaugural project. Meanwhile, they have developed an irreverent, thoughtful, often amusing practice that remained admirably critical of the market fetishization of authorship, originality and young talent.

Until now, I guess, when they printed a big-ass version of Adelman’s photo as it ran in the Times onto a canvas and put it into a “selling exhibition” at Sotheby’s “curated by Vito Schnabel.”

Looks pretty sexy. I hope it’s an edition, so they can give Adelman an A/P.

The Gate: signed and dated 2011 on the overlap

silkscreen and acrylic on canvas

47 1/2 x 67 1/2 in. [sothebys.com]

2005: Water Gate

2009: Things we did not know in 2009: BHQF did The Gate

2009, a week later: Never Mind! Bruce High Quality Foundation made The Gate, but not The Article

Paul Thek’s Tatlin’s Monument

Paul Thek’s birthday was last week, so I probably should have posted this photo of his re-creation of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International then.

Thek installed this version of his Tower of Babel at his only US museum show in his lifetime, at the ICA Philadelphia in 1977. That’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a bathtub full of water inside it there.

Whatever points it loses for verisimilitude Thek’s Tatlin’s Monument makes up for being ahead of the game. The only widely known Tatlin replica at the time in the West was Pontus Hulten’s first version, built in 1968 for the Moderna Museet [where Thek had a show in 1971.] Hulten had made that one with T.M. Shapiro, Tatlin’s collaborator in the “Creative Collective.” Then in 1975, Shapiro went on to make another, more accurate version himself in Moscow, after gaining access to more original notes and documentation.

But then, I don’t get the sense that historical accuracy was ever Thek’s goal.

Previously: On The 2nd Through 8th Tatlin’s Monuments To The Third International

John Pearrault’s 2010 look back at Thek’s work and non-career

The Terracotta Army Of The Internet Archive

Not sure what’s cooler about JWZ’s post about visiting the repurposed Christian Science church that is now The Internet Archive’s San Franscisco Mothership:

their slick and simple book digitizing station setup, or the “terracotta army of avatars of their long-term employees” which are gradually filling the pews.

The Internet Archive [jwz.org]

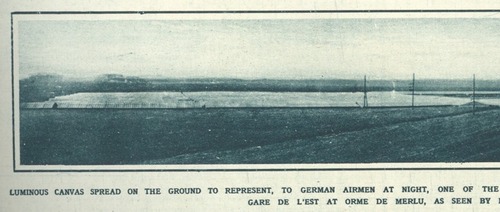

Luminous Canvas, Sham Paris

Sweet, near the end of World War I, Paris planned and began construction on a “Sham Paris,” decoy trains, stations, avenues and factories, to confuse German aerial bombers.

Above, a detail from the photo, “Luminous canvas on the ground to represent, to German airmen at night, oneof the great Paris railway stations: The Camouflage Gare de l’Est.”

Like the 1920 editors of The Illustrated London News, I would have liked some aerial photos of the deception.

A Paris Made to be Destroyed–Sham Paris, 1917/18 [ptak science books]

Suspiciously related: Maskelyne’s Sham Alexandria, or The Greatest Camo Story Ever Told

Same But Different: Charles Ray And Le Grand K

I count it as a matter of pride and oddly satisfying accomplishment to learn I’d been thinking some of the same things about the International Prototype Kilogram that Charles Ray was thinking about the International Prototype Kilogram.

Picture Piece: Same but different, the many ur-Kilos [frieze, jan-feb 2000]

Previously: The International Prototype Kilogram, or le Grand K

Here is the International Prototype Kilogram again

There’s No Such Thing As A Free Lunch

The classic saying, so closely associated with the conservative icon economist Milton Friedman, just sort of came out last night during a brief Twitter discussion with Bill Powhida and Magda Sawon about what, exactly, my point is on Rirkrit Tiravanija’s gorgeous, mirrored objects.

And basically, I think it comes down to my dissatisfaction with what feels like the persistence of a critical adulation of Rirkrit’s socially oriented practice–and, by extension, Relational Aesthetics generally–as anti-market, anti-commodity, gifty experientialism, which does not acknowledge, must less seek to understand and account for, the beautiful luxury goods at the center of so many of these projects.

This seeming contradiction or paradox–I will not call it hypocrisy, at least not on the artist’s part–should be adding a level of complication and contestation to Rirkrit’s work. Instead, it’s reduced to the critical comfort food of free soup and socializing.

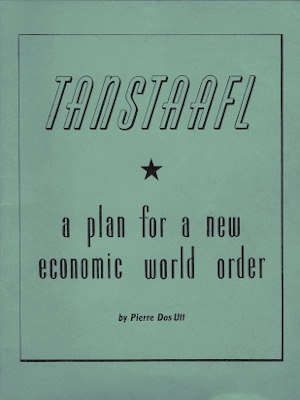

I think Rirkrit knows about the “there’s no free lunch” concept, at least on some level. Thanks to Friedman and to Robert Heinlen before him, who popularized the acronym, TANSTAAFL [There Ain’t No Such Thing As A Free Lunch] in a 1966 sci-fi story about lunar colonists rebelling against their earthly overlords, the saying is pretty deeply embedded in the history of postwar liberalism and globalization, the very political and philosophical context Rirkrit’s work engages [and from which he appropriates so many of his forms.]

So now, against my better judgment, perhaps, I think I want to take a closer look at Rirkrit’s practice and the Relational Aesthetics construct from the perspective of Friedman’s foundational libertarianism. It’ll be like opposition research as art criticism. Or maybe it won’t be. To ignore the highly market-oriented aspects of Rirkrit’s work, and focus solely on the dinner parties and sleepovers is to almost perfectly miss Friedman’s point: nothing comes without a cost; it’s just a matter of identifying it and figuring out who’s going to pay.

While no one seems to be paying much critical attention to Rirkrit’s objects specifically, Relational Aesthetics and its evangelist Nicolas Bourriaud have been worked over repeatedly by other critics in ways that can implicate and/or illuminate these shiny baubles. Claire Bishop, Miwon Kwon, and Stewart Martin are just three prominent voices in the debate, which takes RA to task for both feeble anti-aestheticism [Bishop], and for neutralizing and commodifying social practice within the institutional apparatus [Martin]. I really don’t have the chops or the stamina to lay all this out right now [or maybe ever, who knows?] But the Radical Cultural Research Collective’s RA critique critique provides a handy reference point, as does Dave Beech’s horribly formatted analysis of participation.

What I can do right now, though, is ogle this awesome book cover from 1949, which just became a study for a painting I will have to make. This slim book, TANSTAAFL: A Plan For A New Economic World Order by the hard-to-research Pierre Dos Utt, is one of the earliest published references to “ain’t no free lunch.”

The phrase has its own Wikipedia page, of course.

There ain’t no such thing as a free lunch. [wikipedia]

thanks to Brent for help in approximating Rirkrit’s font for the mockup up top.

Sachs X Ikea X Judd: Great Minds Think Ikea

For he that hath eyes and was paying attention last year, The Selby let him see. For the rest of us, the show at Sperone Westwater is the first time to see Tom Sachs’ awesome Donald Judd furniture hacked together from particleboard scraps from the IKEA AS-IS department.

Hacked is, of course, not the right word. The chairs are constructed with Sachs’ characteristic attention to craft and process: they show every drip of resin, every bubble and lump in the fiberglass joinery.

For me, the best part is that the pieces date from 2009. And in November 2009, the first issue of Bricolage Magazine, Tom’s zine, included a feature titled, “Ikea vs Judd.” Because as awesome as they are on their own, they’re even better for not being Enzo Mari furniture.

Tom Sachs: WORKS, Nov 4 – Dec 17, 2011 [speronewestwater.com]

Tom Sachs site [tomsachs.org]

6.14.10 Tom Sachs in his studio [theselby]

Tom Sachs studio film, by The Selby [vimeo]

Previously, resonant, not related: Enzo Mari X Ikea mashup

howtospendit.com +rirkrit

Thanks to Awl for reminding me that not everyone is not talking about Rirkrit Tiravanija’s sexy, blingy objects. I’d found this last week, but it was crashing my browser, and it may do the same to yours, probably because it’s designed for folks who trade up their computers with the same frequency Steve Jobs traded his AMG SL65.

The Financial Times’ luxury lifestyle magazine supplement How To Spend It loves Rirkrit’s work.

In “Art Works: Spectacular Sculptures – with a purpose,” Helen Chislet delivers servicey with a smile by revealing the “spectacular and tremendous fun” that can result “when artists are asked to design functional outdoor objects.” Objects like Rirkrit’s “ping-pong table of flawless mirror-polished stainless steel in an edition of ten–a piece of perfectly executed workmanship that carries a price tag of $55,000.” [no correction to my original price mention; if you want to pay 10% more that’s your business -ed.] Objects which are still likely to appeal to the FT’s ideal UK-centered international demo, typified by one garden folly maker’s client base as “City workers relocating to the country, but now includes European royalty and “extraordinary people.”

And the Palm Pavilion at Inhotim gets a starring role in “Artward Bound,” Pernilla Holmes’s round-up of far-flung private art parks, which, I love this:

“So much contemporary art is commodified,” says [Doug] Aitken. “A place such as Inhotim works against that. It empowers the artist rather than curating the artist. It’s a phenomenal template for a modern museum.” Unlimited by budget constraints, bureaucracy, timescales and space, such privately owned modern museums are popping up in spectacular, middle-of-dowhere locations around the globe as moneyed art collectros turn the traditional museum model on its head. Each is as unique as the personality of the person who dreamt it up.

Aitken really does have his finger on the pulse of these things.

previously: relational aesthetics for the rich

the gala-as-art movement [vimeo]

Richard Prince And Friends

I’ve tweeted on this a bit already, but it’s really worth repeating: Richard Prince’s appeal of the Patrick Cariou copyright infringement decision is a really great read. The brief was filed last week, and I finally got around to reading on Halloween night. I find it makes a very clear and persuasive argument for throwing out Judge Batts’ sweeping ruling, and it’s a nice, not too esoteric discussion of appropriation and fair use as well.

Basically, Prince, his new lawyers, and Larry Gagosian argue that Judge Batts wrongly applied the prevailing legal standards for fair use, especially the most recent, relevant case which had been before the same court, Blanch v. Koons.

I think I’ve written before that Prince’s work, and his first-round defense, relied very heavily on Koons’s winning argument that an artist’s transformations of size, scale, material, and context were sufficient for fair use. But their briefs almost never cited Blanch and did not make that transformative use argument clearly or well. That has changed.

Prince’s lawyers also argue that Batts overreached and erred by finding all 30 of Prince’s Canal Zone works to be infringing, regardless of what, how, or how much of Cariou’s imagery they contained. And that it’s wrong to force Prince to hand over all the artworks to Cariou when the settled precedent of monetary compensation exists.

I think that, at the very least, the court will find that each painting must be evaluated, and that the court will have to decide Prince’s transformative efforts. While I would love to publish such a document, because it would just be the best kind of worlds-colliding art criticism around, I suspect a check will be cut before the judges take out their rulers.

I could rattle on about this all day, but why not just read it yourself? Here is a copy of Prince’s filing, which I’ll host on my Dropbox own site for a while. The 135-page ruling has a lot of very nice, full color illustrations and clocks in at around 7mb.

[OBVIOUS DISCLOSURE ABOUT GREG.ORG AND THE CREATIVE CAPITAL | WARHOL FOUNDATION ARTS WRITERS PROGRAM, WHICH IS COMPLETELY UNRELATED TO THE FOLLOWING PARAGRAPH, HERE.]

And in even more interesting news, Joy Garnett just gave me a heads up that the Warhol Foundation has actually filed an amicus brief in Cariou v. Prince, warning the courts that if Judge Batts’ ruling were to stand, it would put works by other artists in jeopardy, and would cause “such uncertainty in the field as to cause a chilling effect on the creation of new works.” I expect I’ll come back to this after I read it all, but the Foundation’s brief defends Prince’s work as part of a broad, artistic history of appropriation, quoting, and collage. Should be interesting. The Foundation’s 57-pg brief [pdf] is linked directly here.

Previously: the five most ridiculous things about the Richard Prince copyright decision

The Richard Prince decision? You’re soaking in it!

Richard Prince’s Spiritual America

Size Matters?

“THE WITNESS: This could be a cool book.”

“The Movie is called ‘Eden Rock'”

The View Of Punishment Park From Zuccotti Park

Punishment Park? How did I not know about Peter Watkins’ incendiary 1971, anti-war, anti-fascist, faux-news documentary? I mean, it was the movie Rirkrit chose to broadcast on his unlicensed TV station in the Guggenheim. I sat in Anthology’s rickety seats for the entire 5+ hours of The Commune (Paris, 1871). Is it one of those things that just looks so completely, unrecognizably different in the light of Occupy Wall Street, that–no.

When Punishment Park was finally released on DVD in 2005, it was the peak of a globally unpopular war, which was tainted by torture, unlawful detainment and military tribunals, violations of basic constitutional and human rights, and polarized rhetoric within American culture. So no, I don’t think I registered what Watkins had done.

Which, holy smokes. Here’s how Holland Cotter describes Punishment Park in his 2005 review of Rirkrit’s show:

it is a docudrama about the brutal silencing of antiwar protesters during the Vietnam period. Many of the actors were amateurs. The people cast as activists were, in fact, real-life activists; the police were played by former police officers.

Their lack of theatrical training gives the film a curious tension, making it seem both authentically documentary and stagy. It feels something like that era’s political street theater, which was cropping up all over the United States and Europe at a moment when anger and paranoia were at flood tide. This aesthetic certainly suits the low-tech character of the broadcast facilities, which are pretty rudimentary.

Shooting in an army tent and the Mojave Desert, a British news crew follows two groups of activists/protestors as they are run through a sham tribunal and are given the choice between excessive federal prison sentences and an impossibly brutal three-day race across a vast desert reservation, aka “Punishment Park,” where they are hunted down by National Guardsmen training for the next Kent State.

It’s like Predator and The Tenth Victim gave birth to the sequel of Zabriskie Point, starring the Chicago Seven. It is not pretty.

Punishment Park may not be a great movie, but it is definitely a fascinating one, one which is difficult to watch, and apparently difficult to like. I think that’s by design, though; it seems calculated to antagonize and/or enrage basically anyone with a political opinion and a stake in the outcome of the American experiment. It deserved a little more credit than it got, though, and certainly better consideration than Vincent Canby was capable of:

Because all literature, including futuristic nonsense like this, represents someone’s wish-fulfilling dream, I can’t help but suspect that Watkins’s cautionary fable is really a wildly sincere desire to find his own ultimate punishment.

Yow.

The freaky thing, I guess, is the way Punishment Park manages to both over- and under-predict the cultural rifts and abuses of power in American politicized culture over the intervening 40 years. I think had I seen Punishment Park in 2005, I would have distanced it as a historic, histrionic artifact. But given the last few years/months/weeks, I can’t help but see parallels and hear echoes between the film, its time, and today.

The other, less uncomfortable thing–I mentioned Zabriskie Point for a reason–is how Punishment Park alters the context of the 60s and 70s for me. I can’t help but see the counterculture and the desert, the military and the desert, war and the desert, art and filmmakers in the desert, quite differently now.

The New Yorker Films DVD release of Punishment Park is available on Amazon and Netflix.

Sarah Sze Street View

Just this morning, while I was watching Sarah Sze’s 2010 lecture at the Smtihsonian American Art Museum, and she was showing videos of her installations for the first time [borrowed, with permission, she said, from various YouTube users, which is nice]. And I found myself thinking, “Hah, try running the Google Street View Trike through that!”

But of course, Google already did.

Street View just announced the release of imagery from The High Line, which was apparently captured by the Trike this spring, just before the second, Northern section opened.

And whaddyaknow, there’s Sarah Sze and her crew, installing her bird city, Still Life with Landscape (Model for a Habitat). That’s Sze and her updo on the left. On the LEFT. Focus, people, focus.

And I do believe that is dearly departed High Line curator Lauren Ross with the lanyard, checking in on things. [Happily, Ross isn’t dead; she just moved to Tulsa.]

These photos are actually in reverse order; the Trike was driving south. I haven’t spotted any traces of a Google Guide yet. But I do notice that with this early morning shoot, the Street View pano stitching algorithm erases the Trike’s shadow. Leave no trace.