Sister Andreina holding Yves Klein’s ex-voto for Santa Rita di Cascia in 1999, photo: David Bordes

I get the sense that in the contemporary art world, an artist’s religiosity or spirituality is often perceived as an obstacle, an eccentricity to be indulged when they’re around, but to be politely ignored in serious discussion. That goes for John McCracken, Anne Truitt, Marina Abramovic, a bunch of others, I’m sure, and the one who made me think of it just now: Yves Klein. When the artist’s widow Rotraut Klein-Moquay spoke at the Hirshhorn Museum’s retrospective last spring, it was clear that she was operating on a different, more spiritually attuned plane than the show’s clearly uncomfortable curator, Kerry Brougher. [Though watching Brougher, his co-curator Philippe Vergne, and the Klein Archive’s David Moquay at the Walker a few months later, exasperated interruption may be the only way to get a word in edgewise with the rambling Moquays.]

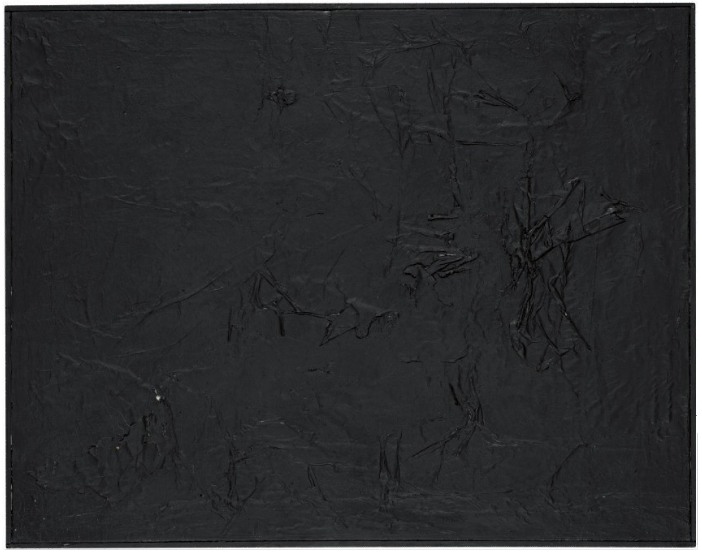

Anyway, Vergne takes it all in stride. In an interview with the Walker’s Julie Caniglia, he tells about securing the loan of one of the most interesting and unusual pieces in the retrospective, a 1961 ex-voto which Klein left at the monastery of Santa Rita di Cascia. It’s like a little retrospective in a box, a boite en valise.

Julie Caniglia

Speaking of striving, you literally went out of your way so that Ex-Voto would be a part of the exhibition. Can you talk about how this loan was carried out?

Vergne

Klein made an extraordinary gesture with this artwork and that’s reflected in how it’s treated by the monastery. I don’t think the Mother Superior would have allowed it to leave the convent without a meeting with one of the exhibition organizers. She was basically saying to us curators, “If you really want this work of art, you’re going to have to come and tell me why. It cannot be treated as one more object. You’re not going to just send a loan form, you’re going to have to come and sweat a little bit because this object is extremely important.”

On the other hand, she was kind enough to meet me at a cloistered convent in Rome so I wouldn’t have to make the long drive to her convent at Cascia. We were in a little room accessible to visitors, but divided wall-to-wall by a table: one side for guests and the other for nuns. They brought me coffee and cookies. Through a translator, we entered this conversation talking about Klein’s work and how important it was to have the Ex-Voto in the exhibition. Then we read the entire loan document word for word, all of the details about insurance and transport, everything. It was really like a ritual. Then we had a conversation about immaterial sensibility.

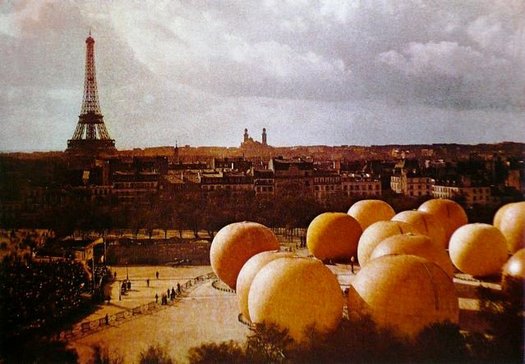

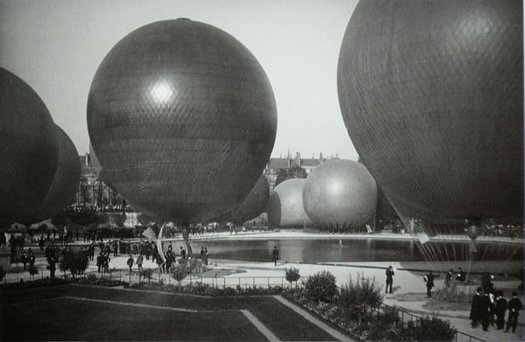

I also got to tell her a story about the well-known Leap into the Void photo–how the house that Klein leapt from outside Paris later became a church dedicated to Saint Rita, through absolutely no relationship with Klein. I thought this was extraordinary, but she said, “No, it’s normal.” I thought she meant for Klein, but she said, “No, for him,” pointing her finger to the sky.

Before I met with the Mother Superior I got to see a part of the convent closed off to the public where some absolutely gorgeous 13th-century frescoes were being restored. That, too, became part of the Yves Klein exhibition for me. I see it as an example of Klein’s immaterial sensibility: I am made of all these little layers of experience, which came together in the making of the exhibition.

Saint Rita is known as the patron saint of lost causes, and was a favorite object of Klein’s devotion and ritualistic interest. He apparently made the ex-voto while experiencing something like painter’s block, and he left it during one of several pilgrimages to Cascia. It was only discovered in 1980, during a renovation at the monastery following an earthquake. It was included in the Centre Pompidou’s 2006 retrospective, but it will return to Cascia after the Klein exhibition closes at the Walker this weekend. Pilgrims, your time is running out.

Yves Klein and the patron saint of lost causes [walkerart.org, thanks to Matt at RO/LU]