UPDATE: NEVERMIND.

I thought of the Fourth Plinth, empty. And the sixteen artists who’ve made sculptures to fill it, (counting Elmgreen and Dragset and the two who are in the queue).

Actually, I thought of the Corgis first. The Queen had had over 30 Corgis, most bred from a dog named Susan, who was given to her on her 18th birthday. Though the royal breeding operation had ceased, in 2022, The Queen still had at least two Corgis and a Dorgi, a dachshund/Corgi mix The Queen and her sister Margaret delighted in since an errant hookup in the 1970s, and which was facilitated, The Queen once actually explained, by the use of “a little brick.”

“The Queen is said to be unwilling to leave young dogs behind when she dies,” the BBC also blithely reported in June, so the thought of some household staff carrying out The Queen’s dying wish to have her dogs killed after her own death–even if it should be a shock–can’t be said to come as a surprise. People should know and remember that decision.

Which is when I thought of the Fourth Plinth. A dog killed and buried with its royal owner. A dog on a plinth. I thought of the Anubis Shrine unearthed in the tomb of Tutankhamun.

The Anubis statue was wrapped in a linen shirt which was from the seventh regnal year of the Pharaoh Akhenaten, according to an ink inscription on it. Underneath was a very fine linen gauze tied at the front of the neck. Over this were two thin floral collars of blue lotus and cornflowers, tied at the back of the neck.[4] Between the front legs sat an ivory writing palette inscribed with the name of Akhenaten’s eldest daughter, Meritaten.

Howard Carter documented in 1927.

No, that’s not the vibe. Anubis led the funeral procession of the pharoah, and, as was evident by the inscription on a “magic brick” of unfired clay found in front of the statue on its palanquin, was positioned to guard the Necropolis:

It is I who hinder the sand from choking the secret chamber, and who repel that one who would repel him with the desert flame. I have set aflame the desert (?), I have caused the path to be mistaken. I am for the protection of the deceased.

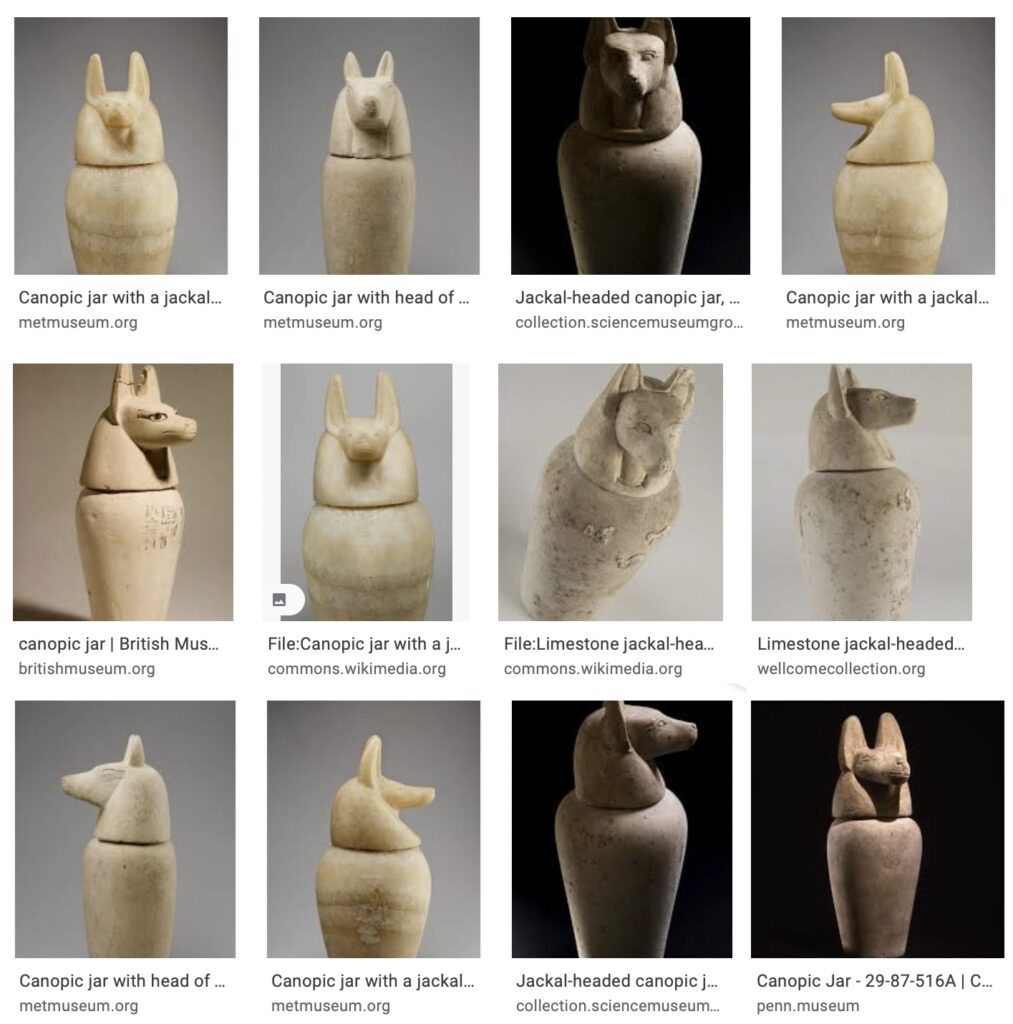

Plus, Anubis is too big. Corgis are small. Like canopic jar small.

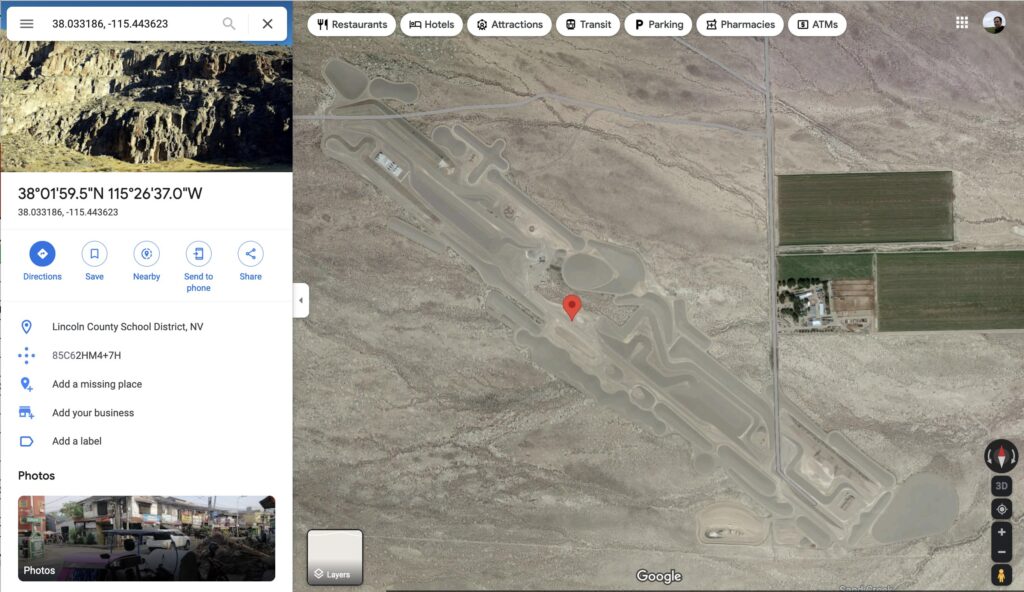

And that is it. So when I looked for an image of the empty Fourth Plinth, I was also surprised to learn that “The Fourth Plinth is Reserved for The Queen.” Even in the mid-2000s, the group in charge of what it calls, “the most important public art commission in the world,” and even the Mayor of London himself were unaware of this plan to commission an equestrian statue of The Queen for the Fourth Plinth after her death. “It’s as if Boris was told the nuclear secret,” a source said to the Independent when the royal family’s plan was revealed to the then-mayor in 2008.

So since 1999 everyone involved in the Fourth Plinth has really just been running interference, keeping the plinth busy–and clear from any competing permanent proposals. Did Elmgreen & Dragset know? Did Hans Haacke?

So it’s been a fait all along, just waiting to be accompli. Fine. Just as long as when the statue of The Queen on horseback is finally unveiled, the edge of the Fourth Plinth is lined with canopic jar-sized memorials to the Corgis The Queen had killed at her death.