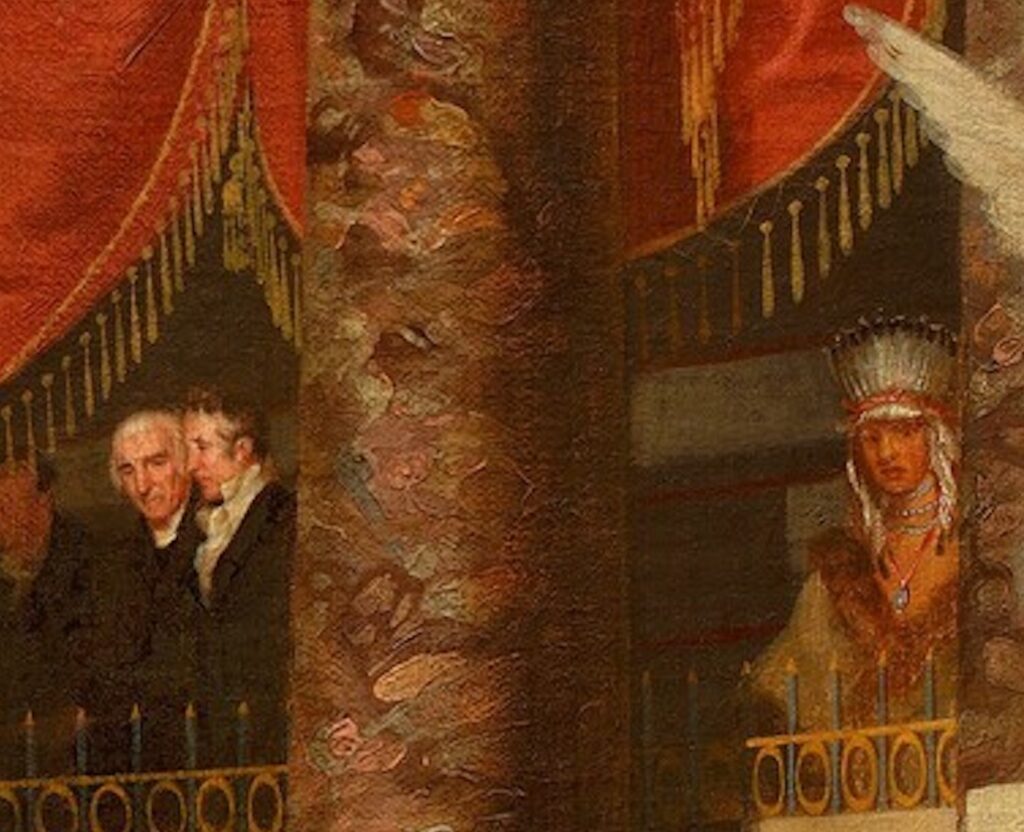

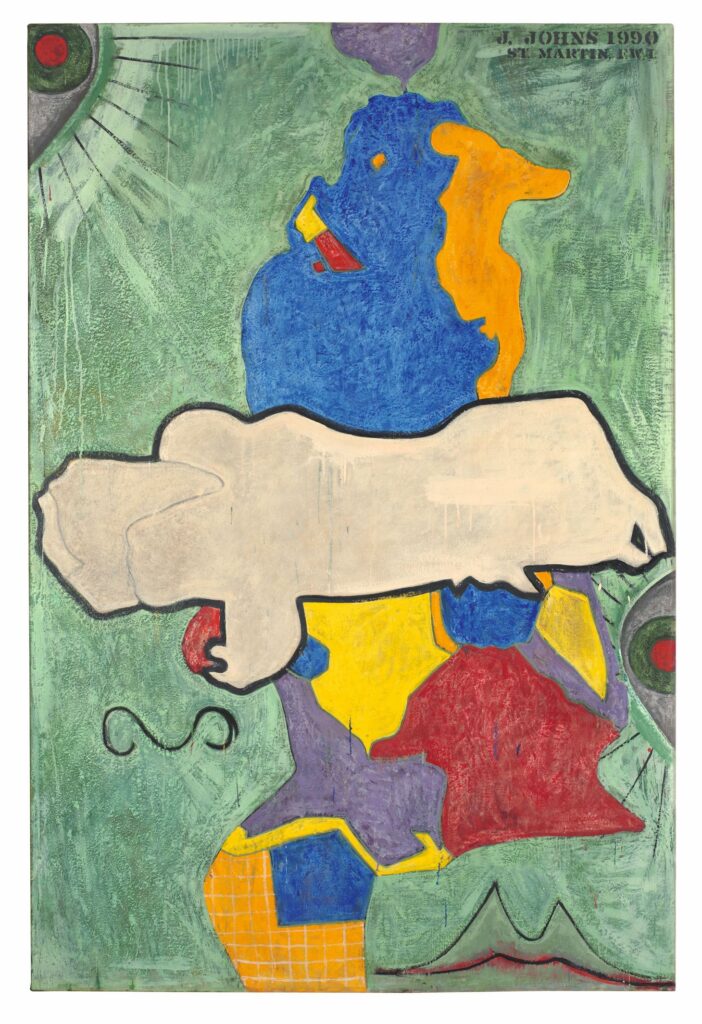

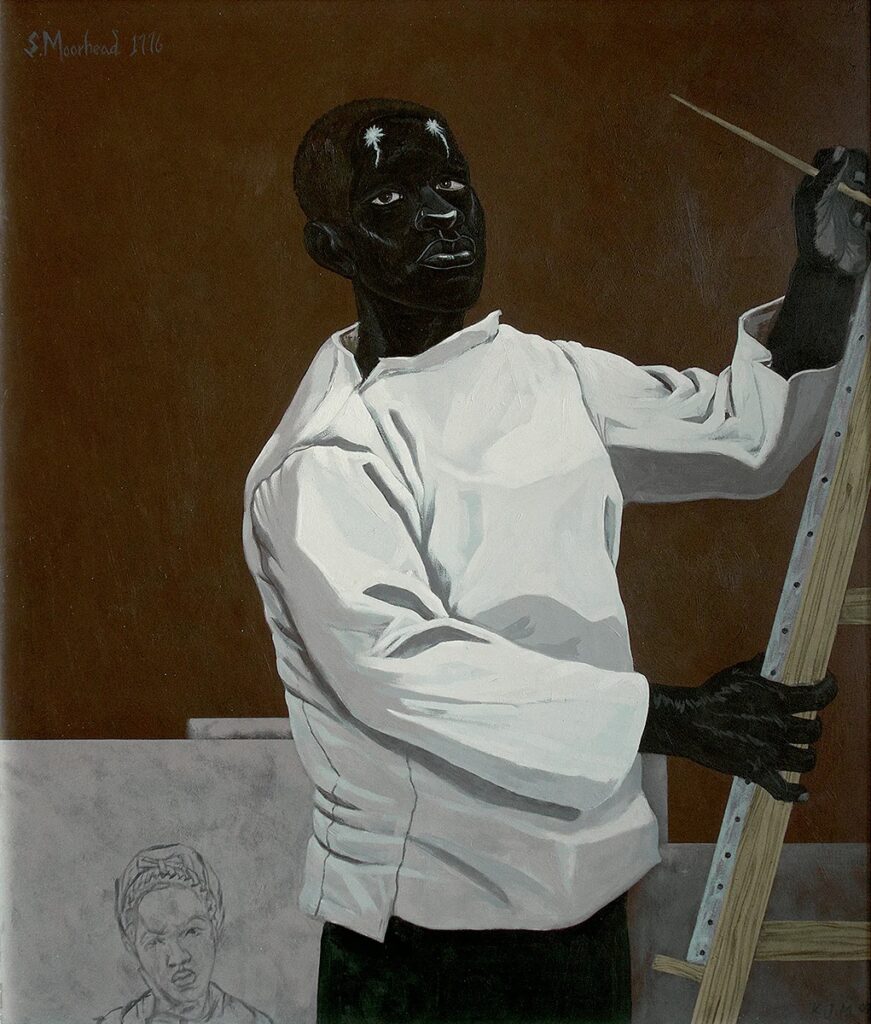

Director Barry Jenkins said one of the inspirations for The Gaze was a painting by Kerry James Marshall. In The Gaze, shot on the set of The Underground Railroad, actors embody ancestors, people who lived and died without much or any visual record of their existence. Marshall created a similar series of paintings depicting Black people of history for whom no visual record survives, and Jenkins called out Scipio Moorhead portrait of himself, 1776, a 2007 painting (above) which he saw at the Met Breuer in 2016. I think Jenkins is quoting a text from the Met:

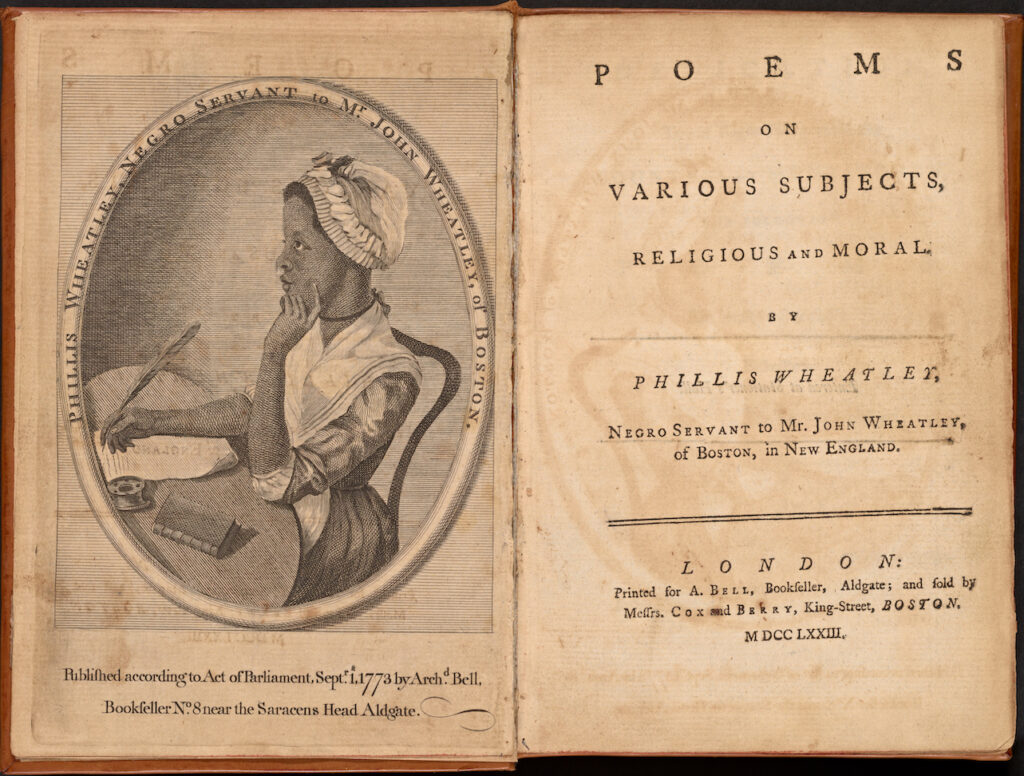

“In this painting Marshall created an imagined self-portrait of a real African American artist, Scipio Moorhead, who was active in the 1770s. Few if any images of Moorhead exist in the historical record. Everything we know of his legacy is based on Phillis Wheatley’s first book of poetry, published in 1773 while she was a slave [sic] in Boston. The book’s title page illustration is an engraving of the writer, reportedly modeled on a painting by Moorhead. The engraving remains the only visual proof, however tenuous, of Moorhead’s existence.”

From what I can find, no images of or by Moorhead survive, only some mentions of him in correspondence; marginalia identifying him as the subject of one of Wheatley’s poems; and the etching that is supposed to be based on his portrait of Wheatley.

Somehow the Met has a print that was not bound into one of the 300 copies the book Wheatley first got published in England. It was soon published in Boston after her return as a free woman, in 1773.

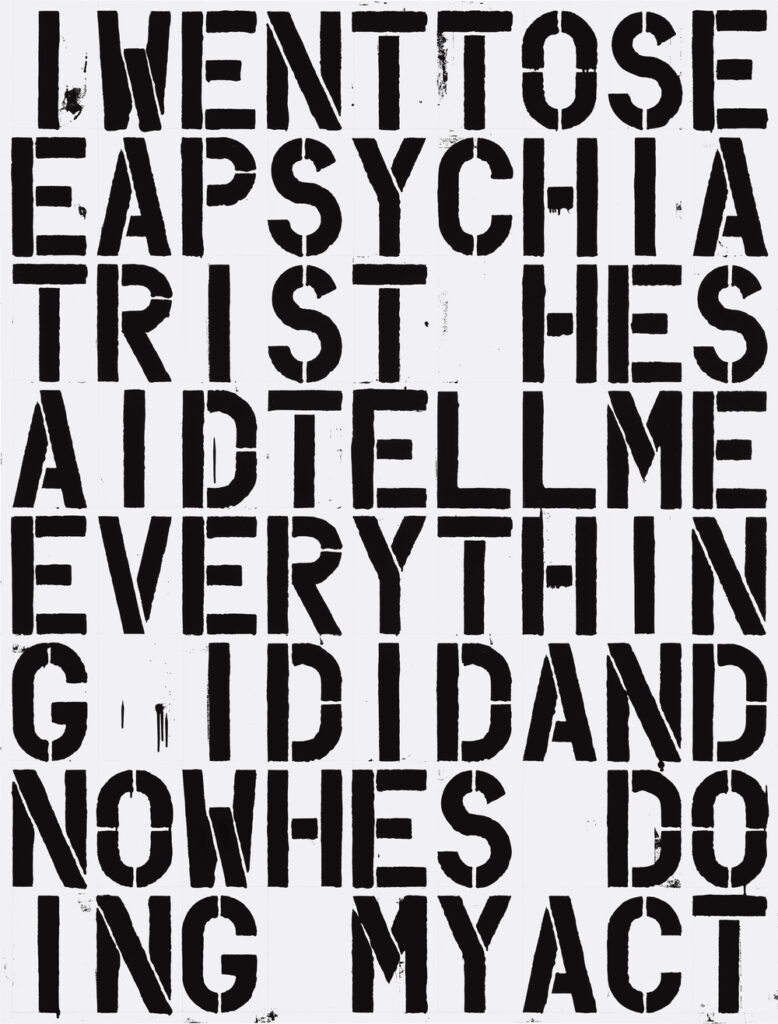

The preface to Wheatley’s book includes a statement signed by 18 prominent Bostonians who examined her and her manuscript and pronounced them genuine, despite her background as “an uncultivated Barbarian” who labors “under the Disadavantage” of being enslaved by the Wheatleys. Which, one must imagine, is an extraordinary thing to have experienced.

Wheatley married, wrote poems criticizing slavery and praising the American revolution, then died young, at 31. A new book by poet and professor Honoré Fanonne Jeffers includes previously unpublished letters showing her husband’s attempts to publish a second book of poetry after her death. Except for Wheatley’s book and a couple of other mentions, Scipio Moorhead’s fuller story remains unknown.

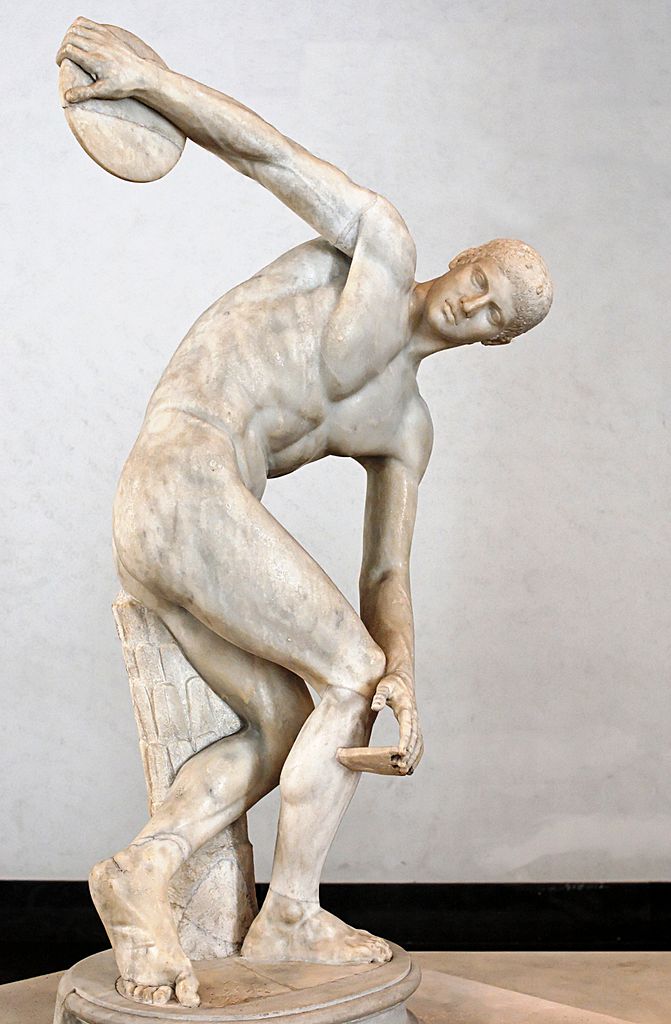

Marshall’s depiction of Moorhead is notable for the size of the historical void it occupies. The greatest sculptors of ancient Greece are only recognized as such because of later Roman copies of their work. Having no known work survive certainly hasn’t hurt the legacies of Phidias, or Polykleitos, who are foundational for European art’s history of itself. What would our culture be like if Moorhead’s Phyllis Wheatley were as influential as Myron’s Discobolus?

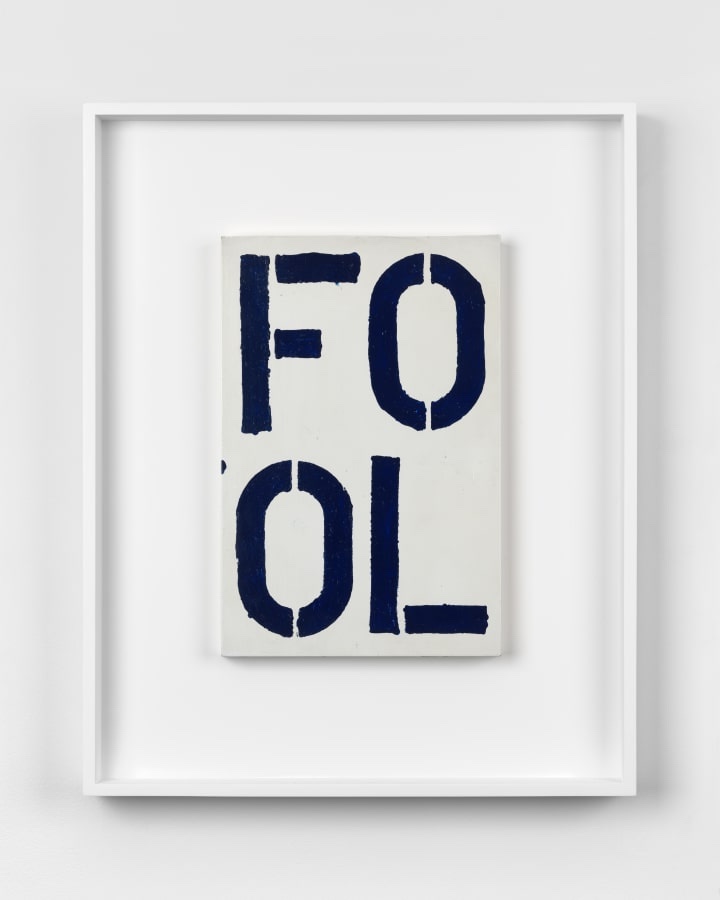

Moorhead/Wheatley Facsimile Object (MW1) is based on the frontispiece and title page of the first US edition of Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, by Phillis Wheatley in the collection of the National Museum of African American History & Culture. At 6.75 x 9 inches, it is true to the octavo size of the original. I’ve been having some issues with cropping, and this one is not quite right, so I think it’ll have to be a proof. But it felt good to get it up in time for Juneteenth.

Previously, extremely related: The Gaze (dir., Barry Jenkins)