North, South, East and West, please vote.

the making of, by greg allen

North, South, East and West, please vote.

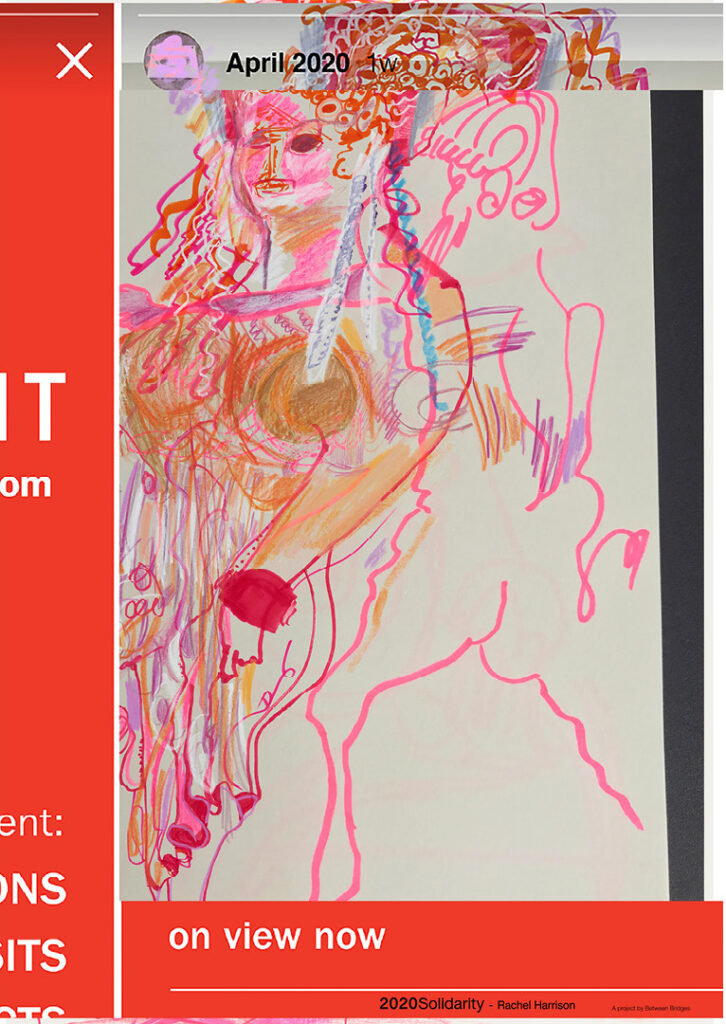

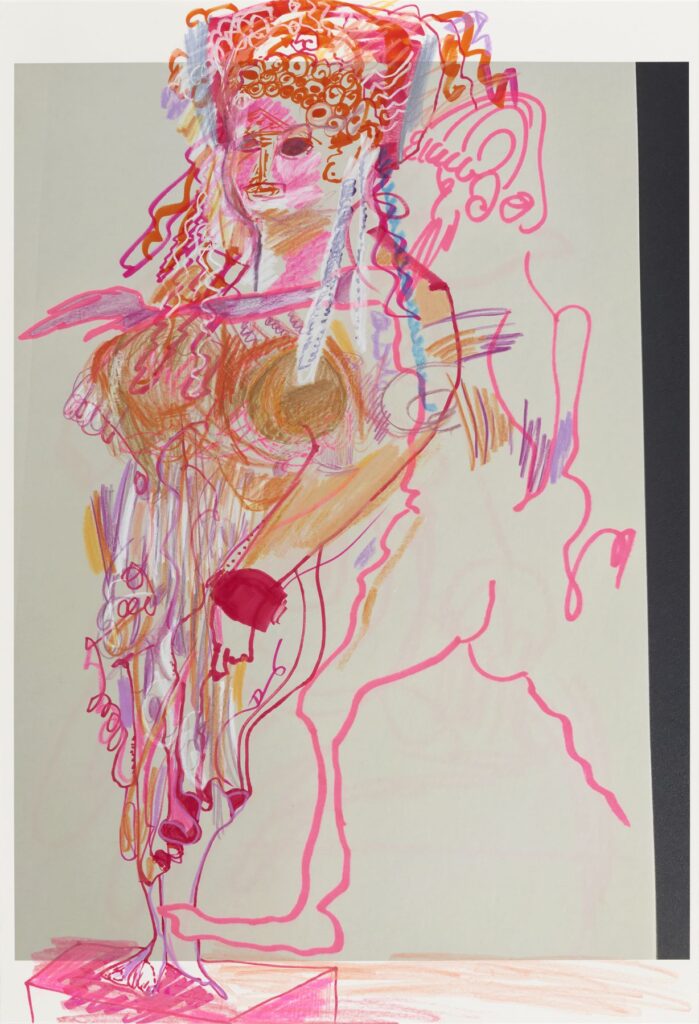

I bought this Rachel Harrison print from Between Bridges’ 2020 Solidarity cultural organizations fundraiser project this summer because I wanted to help the worthy non-profit I ordered it from. But mostly I hoped that seeing it bigger and in person, I’d be able to figure out what is going on in this image. So far, I’m still stumped.

It is a digital collage of a screenshot, with a crop&drag of one of Harrison’s works. The date and the avi feel like a Photos app interface? I have tried and failed to identify the red menu UI of what looks like a museum, or a gallery guide website: (“Exhibitions”? “Visits”? “Thots”? OK, probably not that last one.)

The drawing, titled, The Classics, is one I recognized right away from Harrison’s show this spring at Greene Naftali. Not that I saw it in person, of course. (Did anybody?) But it’s not just a drawing, but a drawing in pencil, ink, and crayon on an inkjet print–of what looks to be a cropped image of a drawing. That got chopped and overworked again. I think the pink line drawing of a male figure was on the original sketchbook page, and the elaborate female figure was drawn on the print. As Anne Doran notes in the conversation-with-the-artist-slash-press-release, “[T]hese are drawings on photographs of drawings of photographs of sculpture.”

“In the nineteenth century a series of major excavations of Greek and Roman statues were documented by French and British photographers. The relationship of the camera to sculpture goes back to its [photography’s, presumably. -ed.] invention,” Harrison replied.

It [the drawing] was a remediated object from a show that got locked down, re-remediated into an image that was sent out to propagate around the world. As another kind of object.

Anyway, I guess now I’m throwing it [the image of the print] out there, if anyone has any insights, lmk?

2020Solidarity [betweenbridges.net]

Rachel Harrison Drawings, 6 March – 31 July 2020 [greene naftali]

Phillips, in recognition of this globally significant moment and in

reflection of the ever-relevant and flexible nature of Darren Bader’s work, invite you, and 999 other

diverse invitees, to become an active part of the total “site” of an expansive physical exhibition. You are

invited to be a “place” in the official installation of a work by Darren

Bader, in the location of your

choosing, by following the parameters of this exhibition:

Darren Bader

Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person? – Clarice Lispector “I know, but there are lots of parts of being a person, you know?” “Yeah, I know”. Anyone who lives, knows, even without knowing, that he or she knows – Clarice Lispector

Fortune cookies

Overall dimensions vary with installation

Original installation: approximately 1,000 fortune cookies

October 21, 2020

The opening of this exhibition is also in honor of and in conjunction with the launch of the

Darren Bader Foundation’s new website

An integral part of the work at the center of this exhibition, Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person? – Clarice Lispector “I know, but there are lots of parts of being a person, you know?” “Yeah, I know”. Anyone who lives, knows, even without knowing, that he or she knows – Clarice Lispector, 2013 (and of many of Bader’s other malleable works), is that the owner has the right to make certain decisions and interpretations of the specific yet open-ended parameters of the work, each time they manifest the work. When lending the work, the owner is thereby temporarily lending to the authorized borrower the owner’s rights and responsibilities to take on these decisions and interpretations, specifically for the length of the loan. This work is for sale in this exhibition courtesy of a private collection. The curator and representative of the authorized agent for this exhibition is Phillips.

CORE TENETS of Who has not asked himself at some time or other: am I a monster or is this what it means to be a person? – Clarice Lispector “I know, but there are lots of parts of being a person, you know?” “Yeah, I know”. Anyone who lives, knows, even without knowing, that he or she knows – Clarice Lispector, 2013 [and all Bader candy works]:

The work can exist in more than one place at a time, as its uniqueness is defined by ownership.

An intention of the work is that it can be manifested with ease.

When the work is manifest, individuals must be permitted to choose to take pieces from the work.

The owner (or authorized borrower) has the right to determine if and how the work is regenerated during the course of an exhibition/installation.

The owner (or authorized borrower) has the right to interpret/choose the mode, configuration, and placement of installation for each manifestation.

The work exists even if it is not manifest.

A manifestation of the work is only the work if it is installed by the owner or in the context of an authorized loan.

An authorized manifestation of the work is the work, and should only be referred to as the work.

This work is a certificate of authenticity signed by the artist and the fortune cookies are to be sourced locally by the buyer.

Estimate £8,000 – 10,000. [UPDATE: Sold for £7,000 8,280, cookies not included.]

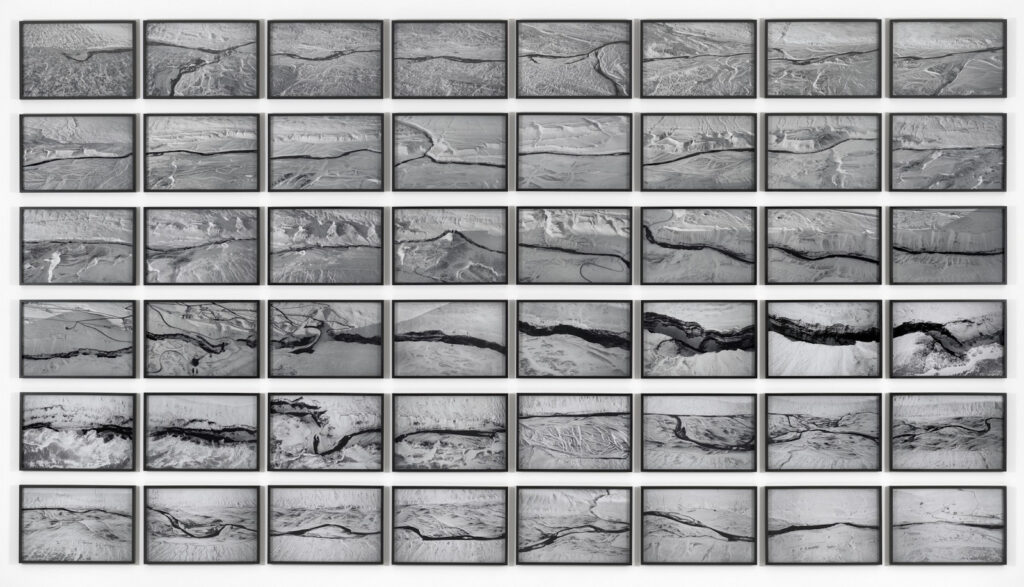

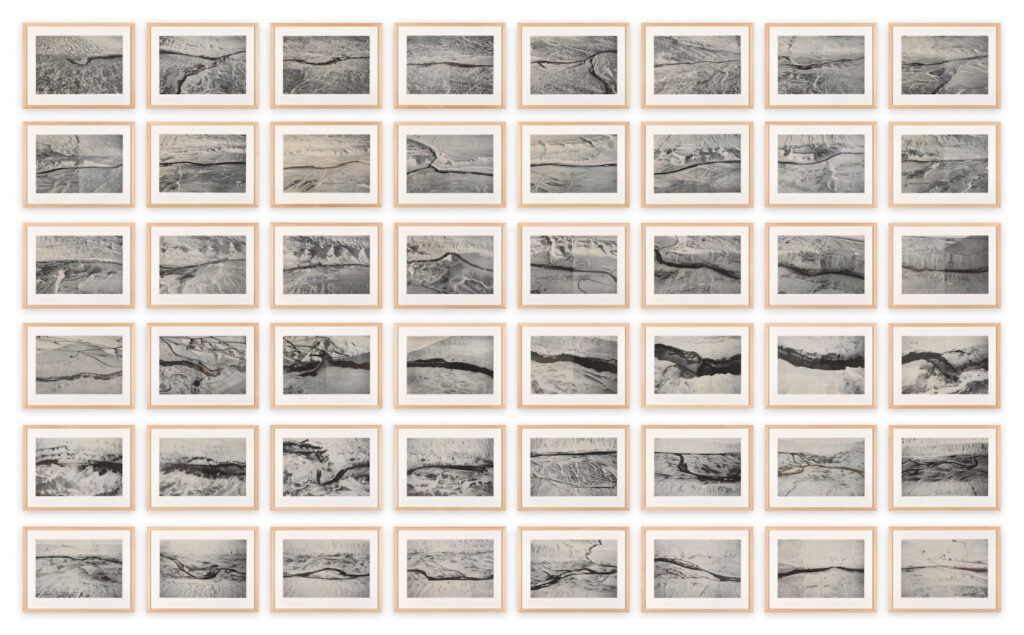

In 2004 Olafur Eliasson made The Jokla Series, a grid of 48 aerial photos of the Jokla, a river fed by Iceland’s largest glacier, Vatnajökull, which was threatened by the proposed construction of a large dam to power an aluminum smelting plant. Aerial traces of a river’s path and hydroelectric construction sites had each been the subject of a photo grid before, in 2000.

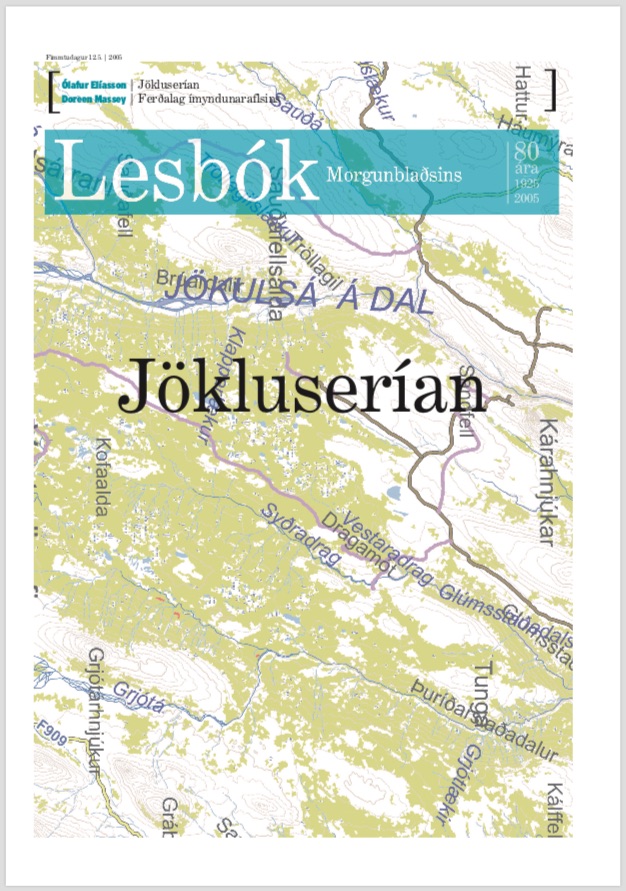

But by 2004 Eliasson’s prominence, and the significance of the Jokla damming controversy brought added attention to his examinations of the Icelandic landscape. In May 2005, Morgunblaðið, the largest newspaper in Iceland, published a special standalone issue containing all 48 Jokla photos, plus an essay on place by Doreen Massey.

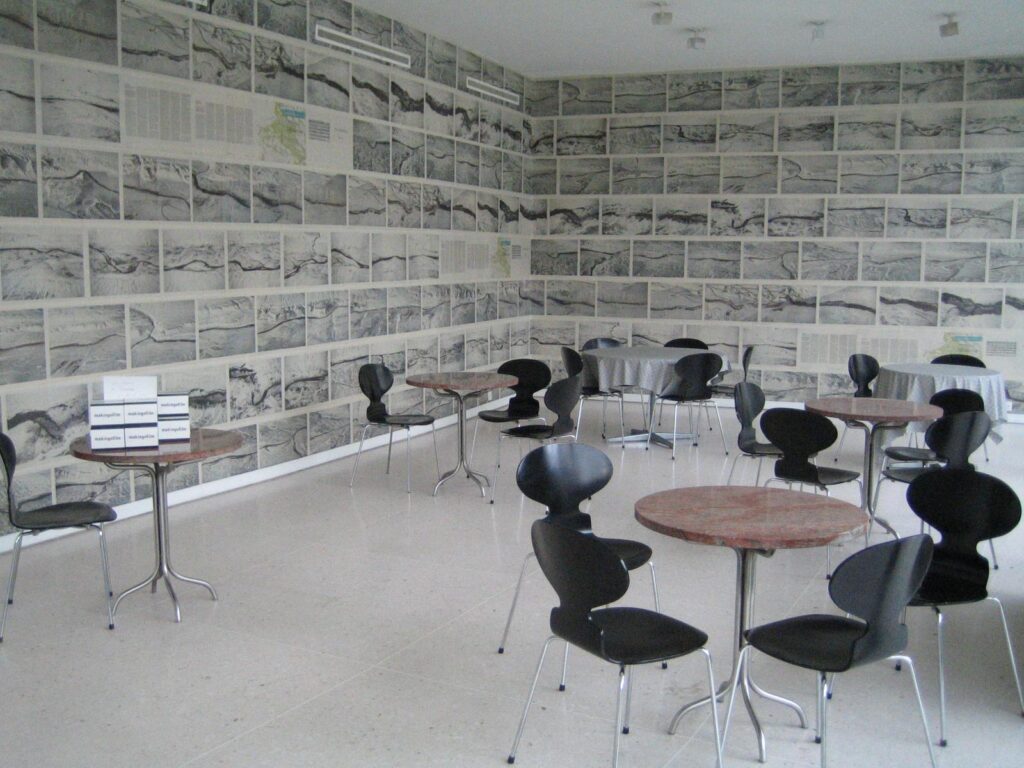

Later in 2005, Eliasson opened a show at the Kunsthaus Zug titled, “The body as brain.” Eliasson installed copies of the Morgunblaðið Jökluserían issue as wallpaper for the Kunsthaus Bar. The show remained into 2006 as part of “Projekt Sammlung,” or “collection project,” a multi-year collaboration with the innovative institution, “an artistic process in which the viewer, the work and the museum mediate anew with regard to the constitution of reality.”

Though the aluminum dam got built and the river got screwed, and the Projekt Sammlung was successful, but is dormant, The Jokla Series continues to mediate anew with regard to the constitution of reality. An extraordinary photo grid is for sale at Sotheby’s next week, which is titled The Jokla Series.

Its dimensions and framing differ from the The Jokla Series in MoMA’s collection, and each photo, described as c-prints by the auction house, has, not a crease, but a seam down the center.

I think they are the prints from the Morgunblaðið Jökluserían issue–two issues, actually–cut and pieced together, as the wallpaper was, and framed à la Eliasson (except for those mats, obv), by a Danish, not Swiss, framer, who I think even wrote the page numbers on the verso. If they are indeed c-prints (I’m waiting for the condition report*), then they are rephotographed images of the assembled newspaper prints, which is even more extraordinary. Olafurian reality is constituting around me anew as I stare at my screen in awe and admiration. I mean, the framing alone had to cost EUR5000.

The provenance states they came from the artist, and thence by descent, so one degree of separation from the origin/al owner. All of this is happening in the bright light of the art world assembled, at one of our most august mercantile institutions. So if this collection project stays around until the hammer drops, it will indeed be an exceptional work, with an exceptional backstory. And if it doesn’t, well, as glaciers and the rivers that flow from them can sadly attest, things we look to for permanence can suddenly change, or even disappear.

[*next morning update: this lot was withdrawn. so of course now I want to buy it.]

22 Oct 2020, Lot 292 “Olafur Eliasson, The Jökla Series, 2004,” est. GBP 50-70,000 [sothebys]

In conjunction with the third volume of his memoirs, Years of Renewal, covering his post-Watergate tenure as both Secretary of State and National Security Adviser in the Nixon and Ford administrations, which was published in 1999, Henry Kissinger created little thank you gifts for his influential friends.

Sterling silver milk pitchers 4.5 inches high, with a machine turned collar and reeded handle were engraved with the book’s title on one side and

THANK YOU

LOVE, HENRY

on the other. Their stamp identifies them as the c. 1995 work of smith J.A. Campbell, whose assortment of sterling silver gifts, including engravable silver lids for marmite or Heinz Ketchup, but not these little milk pitchers, are (at present) sold online at The Silver Company.

The Rockefellers’ jug sold for $5,265.

Another example from what is now an edition has appeared in public, in the sale, ending tomorrow, of the personal collection of Mrs. Jayne Wrightsman, the socialite and French furniture and bookbinding connoisseur who was an extremely influential trustee of the Metropolitan Museum, as well as being in Nancy Reagan’s cabinet.

With less than 18 hours to go, Mrs. Wrightsman’s jug is currently at $1,100. [update: it sold for $4,000.]

This edition will trace the strategic social relationships Kissinger cultivated in the New-York-socialite-meets-consultant-elder-statesman-who-eschews-travel-to-certain-Geneva-Convention-signatory-countries phase of his career. Or it might just map to the acknowledgements in his book, which could be the same thing. Either way, just as with the reflections of the lightboxes in the photos of the respective jugs, the circumstances of this work’s making will gradually come into clearer focus.

15 Oct 2020, Lot 574 AN ELIZABETH II SILVER PRESENTATION MILK JUG, est USD 400-600, sold for USD 4,000 [christies]

11 May 2018 Lot 1445 AN ELIZABETH II SILVER PRESENTATION MILK JUG, est USD 200-400, sold USD 5,265 [christies]

Kissinger, a longtime Putin confidant, sidles up to Trump [politico]

Previously, related: Unrealized Rockefeller Diptych, (1650–2018)

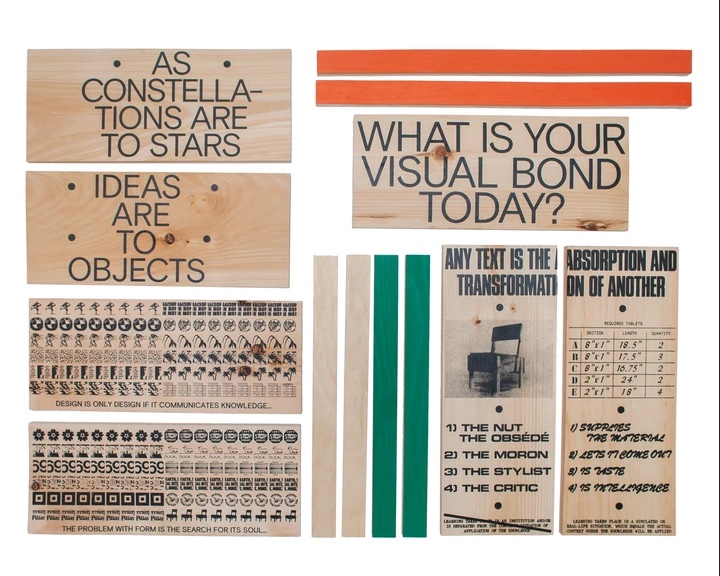

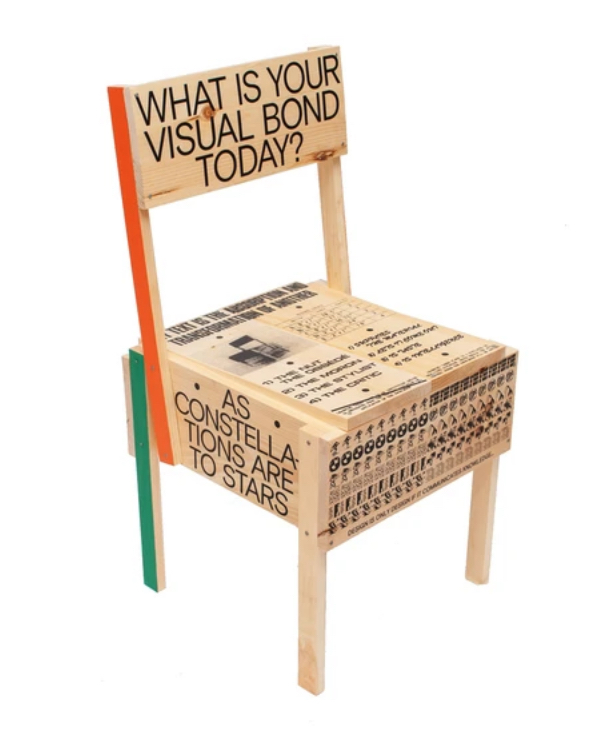

That Boot Boyz Biz’s flow of ideas and synthesis of meaning and circulation of dialogue could not ultimately be contained within the medium of the t-shirt should surprise no one, not even those who once imagined it infinite.

Last year the ideas of Dziga Vertov via Hito Steyerl, Walter Benjamin, Julia Kristeva, and Susan Sontag were published in Enzo Mari autoprogettazione chair format [their second furniture drop]. You’ll have to do the work of assembly to see the results, but Boot Boyz have made sure the right parts are there, that they’ll fit together, and that it’ll look beautiful when you’re done.

Sedia I [boot-boyz.biz, thanks again, @stottleplex]

While we’re on the subject of writing quickly on matters of significant art that happened in the part about which I had absolutely no idea, please direct your attention to the Boot Boyz Biz, an anonymous bootlegging collective which has, since 2015, been publishing major art and design content, primarily in the medium of deeply researched and highly synthesized, extremely limited edition t-shirts. Which is the only reason, besides my willful neglect of the instagram platform, that I can come up with for my sleeping so hard and so long on them.

Anyway, the t-shirt drops are somehow surpassed only by the non-t-shirt drops, two of which I will highlight here:

One: last summer the Boot Boyz made a Tilted Arc Defense Fund tufted wool rug. I might say it’s more of a mat, but what matters is, it exists at all, unlike the Richard Serra sculpture it evokes, obv. It captures the view from the haters’ offices down to the plaza below, in tufted wool, tastefully tinted to evoke the fundraising poster that Serra and Friends put out.

For the 7 billion-plus of us who did not cop the rug, the sidebar of historical and theoretical research will have to suffice.

Tilted Arc Rug [boot-boyz.biz, thanks @stottleplex!]

“Sometimes I put clothes on the sculptures,” is how David Hammons revealed a previously unpublic intervention to Public Art Fund curator Daniel S. Palmer, who in turn has revealed it to us in The New York Times T Magazine.

For five or so winters, beginning around 2007, Hammons wrapped warmer clothing around a 19th century statue in Brooklyn of a formerly enslaved woman standing at the feet of a sculpture of a much more warmly dressed white abolitionist Henry Ward Beecher.

At least, that’s the photo we see, of the action we know. “I put clothes on the sculptureS.” Where are the others?

Remember, this is Hammons’ M.O. He only publicly showed his iconic Pissed Off nine years after he’d urinated on that Richard Serra sculpture. And of course, it’s iconic because Dawoud Bey photographed it.

How long will it take for us to get it through our heads that we are surrounded by David Hammons’ artworks we don’t even know about, and may only find out about years later, if we’re lucky?

Unless we can scan back through Instagram–2007? We need to look at flickr!–to see if anyone happened upon Hammons’ sculptural caregiving while walking the dog, and happened to take a picture. Some day maybe an algorithm will unearth unseen Hammonses from our global photographic record, like LIDAR mapping ancient cities in the jungle. But for now, we don’t even know who took the one photo we have.

[cf. putting little hats on Jizō in Japan]

A poignant take on the controversy surrounding public monuments [nyt]

Previously, very much related, 2018: Pissed Off: Can you hold it?

2013: Stop and Piss: David Hammons’ Pissed Off

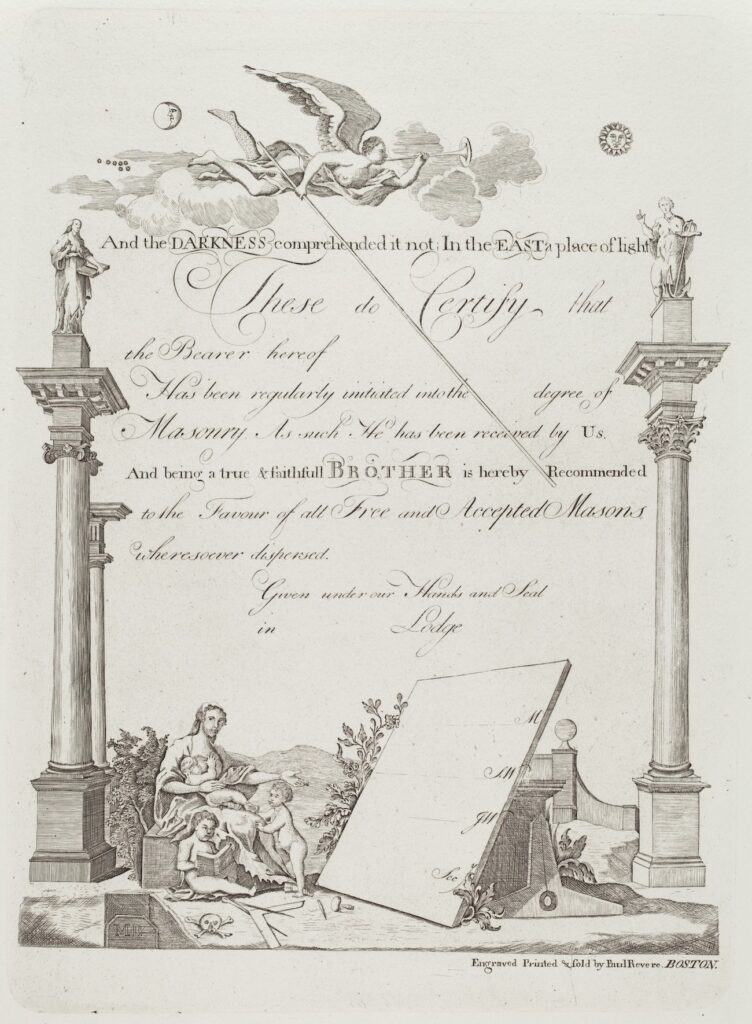

Before Sears scion Lessing Rosenwald donated the copper plate engraved on both sides by Paul Revere to the National Gallery of Art, he had around 24 copies of this Masonic certificate made. One sold in 2014 for a couple of hundred dollars.

But this print was made from the plate in 1954, the year after the National Gallery acquired it. And it came from the Rosenwald Collection, but not until 1980. So I guess Rosenwald wanted one more copy on the way out the door. When you’re a founding benefactor donating 22,000 objects, they let you do it.

Anyway, I want to make some, too. But for the moment, I’d settle for seeing the plate. The drawings are wonky, but the script is absolutely gorgeous.

Paul Revere, Masonic Certificate, restrike print by Herbert Pasternack [nga.gov]

Paul Revere, Masonic Certificate [verso], engraved copper plate [nga.gov]

Previously, very much related: Paul Revere (attr.), Time Capsule Plaque, silver, engraved text, c.1790

Hop, skip, and a jump to: Untitled (Andiron attributed to Paul Revere, Jr.), 2014 (sic)

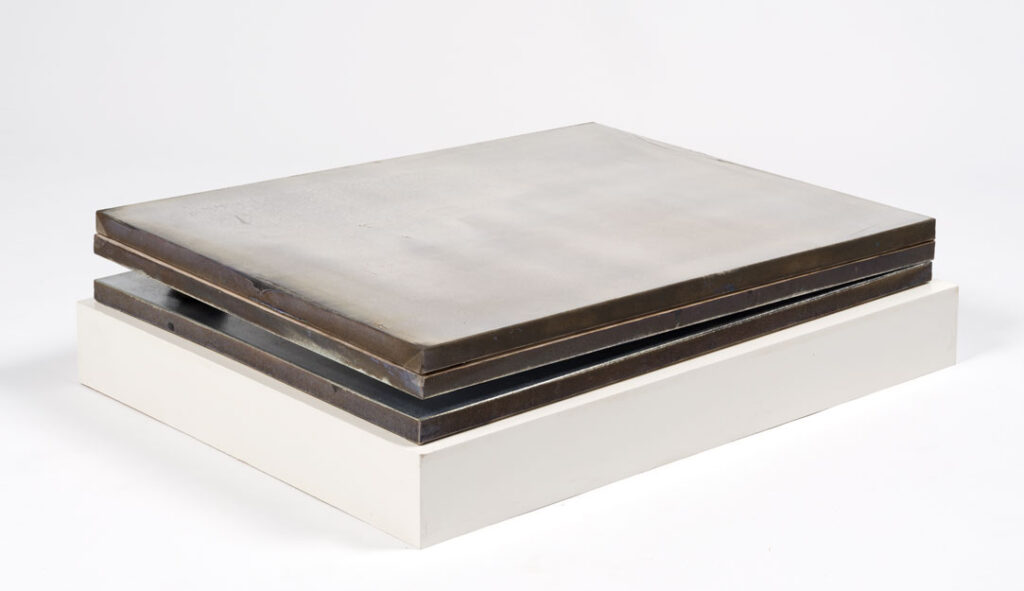

Jacob Kassay’s silvered paintings appeared in early 2009, “elegantly abused luxury goods” whose distorting mirroring surfaces were instantly desirable to collectors. Then their glinting allure proved irresistible to financial speculators whose only lesson from the recent implosion of the global financial markets was that they’d never face any consequences.

Then and now, Kassay worked through the wave of flipper interest as it crested, crashed, and inevitably moved on to swamp the next young artist’s practice.

The untitled work at the literal center of the Eleven Rivington show comprises three silvered canvases, separated slightly by an unseen rock, resting on a wooden plinth.

According to LA Modern’s provenance, it has changed hands once; the original 2009 buyer (from Florida, save that sales tax!) sold to someone in Los Angeles, who is now selling it.

It is not clear for how much this ur-Kassay changed hands–or when, but it was after trying to sell it for $150k in 2012, and certainly for more than the current estimate. This could be your chance, savvy connoisseur, to acquire a beautiful and historic work of the artist’s, restore balance to the force, and cause someone to lose a hundred thousand dollars, all at once.

Oct 18, 2020, Lot 157: Untitled, Jacob Kassay, est. $40-60,000 [lamodern]

update: it didn’t sell. that we know of.

May 2021 update: This major work appeared at auction again, at Rago, and because I was unable to keep track of what day it is, I missed it selling on May 19, where it sold for $4,550, including premium. I am hugely bummed to have not bought it, but applaud the connoisseur who did. Of course, if there’d been another bidder, the price would have been higher. Anyway, HMU, winner!

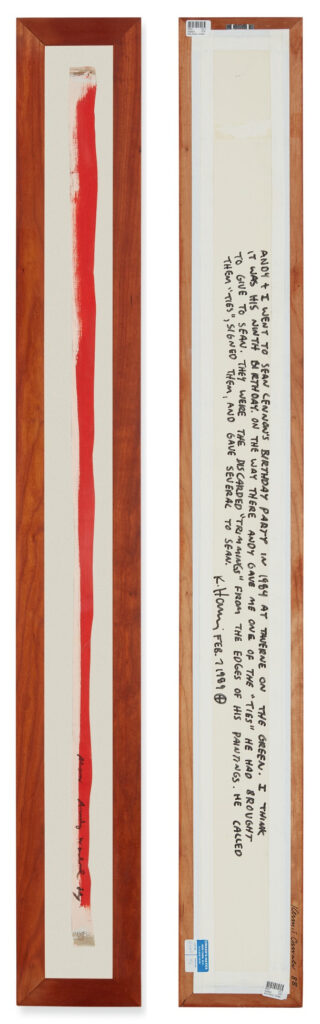

What was Andy Warhol painting red in 1984 that he cut the edge of off after stretching it, and then signed it?

Andy + I went to Sean Lennon’s birthday party in 1984 at Taverne on the Green. I think it was his ninth birthday. On the way there Andy gave me one of the “ties” he had brought to give to Sean. They were the discarded “trimmings” from the edges of his paintings. He called them “ties”, signed them, and gave several to Sean.

is a thing Keith Haring wrote on Febuary 7, 1989, four and a half years later, on the back of the Warhol “tie,” that his buddy Kermit Oswald had already framed and signed himself in 1988?

Oswald was a childhood friend of Haring, and they stayed tight. He’s been head of the Keith Haring Foundation for decades. He ran a framing and fabrication shop after moving to New York with/to see his buddy. He talks of basically curating/producing/installing Haring’s shows. And he also jointly signed a lot of Haring’s work. It’s interesting to see his contribution to, say, these early painted cutout figures from Haring’s first show at Tony Shafrazi being explicitly circumscribed to “providing the wood.” As if the guy who picked up the plywood always signing things as “Copyright me” is just how things work.

Isn’t it more logical that the guy with the woodshop cut the figure, the guy with the marker drew his design, and then the guy with the woodshop routed it out and painted it in–and then signed his name first?

Anyway, point is, the Haring market seems to tell itself an awful lot of stories to make itself feel good. But the Warhol signed garbage given to Keith in a cab and turned into A Work by Kermit which Keith documented and signed later market seems to be doing just fine. At the Haring Estate stoop sale last week, this thing got a title and sold for 40x its estimate. I’m sure Sean is rummaging through his closet as I type.

In the mid-1960s, with his arthritis acting up, and after decades of designing stage sets for the London theater, Oliver Messel began designing houses on Mustique for fancy people like Princess Margaret, the hard-partying sister to Queen Elizabeth, who’d married Messel’s nephew Antony Armstrong-Jones (aka Lord Snowdon)*.

Messel bought himself a house on Barbados, and renovated it into his Caribbean fantasy show palace with his partner of 30 years, Vagn Riis-Hansen. It would seem, by my rough calculations, at least, that Riis-Hansen spent most of that time embroidering this rug.

It is nine feet wide, and ten and a half feet long, and it is gros-point, a large-stitch needlework technique, made on four panels, each 30 inches wide. The pattern is inspired by Aubusson rugs of 18th century France.

Can you just get a pattern for making an Aubusson rug? Do you have one created after your own Aubusson and counted out? [Messel designed fabrics, scarves, and at least one unproduced Donegal carpet.] Do you stencil it onto the heavy grid of fabric that is your base? Do you complete each panel, and then stitch them together? Are they ever off by a row?

It is not that I, who have been typing on a computer for thirty years, am unfamiliar with tedious, repetitive, and precise handwork. But I am at a loss to picture Messel and Riis-Hansen entertaining the international jetset while also one of them is sewing a big-ass rug for days or nights on end. I feel like I’m missing some key details about the making of this rug.

OK, for starters, it looks like it was in Messel and Riis-Hansen’s apartment in London, which was published in Architectural Digest in 1963, and presumably photographed in 1962. It does not look new. This recap article on AD calls Riis-Hansen Messel’s lover AND manager**, since the 40s. Also, he was apparently, big, and gruff, and annoyed his in-laws and Cecil Beaton, who nicknamed him The Great Dane. And he still found time to embroider a giant carpet.

In 1978 Messel died, a year after Riis-Hansen, and Armstrong-Jones got the rug. In 2017, Armstrong-Jones died, and now anyone can get the rug, if they move in the next three days.

Lot 103: A GROS-POINT NEEDLEWORK CARPET WOVEN [sic?***] BY OLIVER MESSEL’S PARTNER VAGN RIIS-HANSEN, est GBP 1500-2500, ends 24 Sept 2020 [update someone bought it for GBP1000, the opening bid.][christies.com]

[update, somewhat related: In 2012 artist Matthew Smith created an exhibition and archival intervention at Nymans, the Messel family’s house to bring Messel and Riis-Hansen’s relationship into parity with the other family stories depicted at the National Trust property. (pdf)]

*Apparently Messel did not attend the 1960 wedding because he could not bring his partner. Or maybe his partner was busy sewing a massive rug.

**Thinking of this while doing the dishes just now I remembered reading a memo from Walter Hopps in the Smithsonian archive of the 1976 Rauschenberg retrospective, saying that though the museum would cover the travel expenses of artists and their wives, they would not pay for Bob’s “friend.” [scare quotes in the original] Maybe if Messel and Riis-Hansen were traveling together in an era where their romantic relationship was literally a jailable offense, being a manager would offer all the explanation they’d ever need.

***Maybe this whole post is a misplaced over-reliance on one word, which feels inaccurate technically–does someone stitching a rug consider it weaving?–but which must reflect a received story, if not a history per se, of how this rug came to be, and why it was kept? Or maybe it’s just so obvious to anyone interested or involved that “woven” means “had woven,” and you’d have to be daft to entertain the notion that it should be considered literally? And what possibly could be going on in this, the approaching autumn of the Year of Our Lord 2020, that could possibly account for channeling this much mental space into the backstory of some knockoff Aubusson rug an ancient British playboy stashed away after cleaning out his gay uncles’ Barbadian retirement cottage? What, indeed.

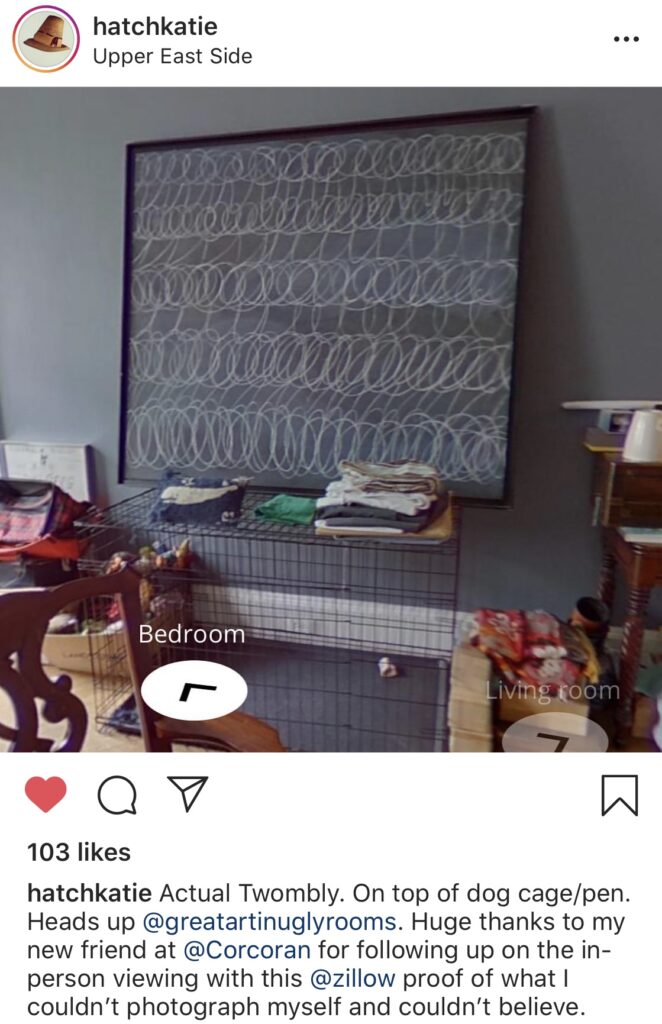

Before anyone gives Cy Twombly on a dog crate the crown for greatest art in real estate listing photography, please check out the listing for the former Ice House of the Vanderbilt estate that was Dowling College, which went bankrupt in 2016 and was liquidated in 2018.

That is Cady Noland’s Tower of Terror (1993-94) in all its in situ glory. Can you even imagine? A pleasant walk past the massive, aluminum group stockade on the way to campus. I guess the bench was in the shed.

Cady Noland was not consulted and does not approve of these photos, but they have been certified by Douglas Elliman. The ice house sold for $376,938. The sculpture sold for $2,207,501. [Thanks greg.org reader dg]

Previously, related: Cady Noland GOAT

The subject of precariously perched Twomblys prompted Claudio Santambrogio to email, wondering about the painting on the left in this iconic 1966 Horst photo. Surely, it’s not a Twombly.

My first check, of Google, turns up many of the times this Vogue photoshoot of the House of Franchetti-Twombly has been re-published and discussed, and absolutely none of them have a caption or credit for this painting. This shoot is legendary, but atmospheric.

It is also marketable. I have not pinned down when it happened, but there is something swirling around the web in upscale, merchy places like 1stdibs and Artsy, called The Cy Twombly Rome Portfolio. Horst’s images, made for and owned by Condé Nast, are available in limited editions in various sizes, with the “authorization” of the Horst Estate. Interestingly, though, less than half the Twombly photos feature Twombly’s paintings. This feels like a mix of adding the entire contact sheet to the shopping cart, and the Twombly Foundation flexing its vetoing muscles.

Anyway, there is no such compunction to publishing the photo of Twombly’s Richter (Untitled #6), or a straight-on shot of this painting (Untitled #12). None of these photos have caption or credit information (or a Nicola Del Roscio to keep them in line.)

Next step: the date of the photo puts a pretty tight constraint on who it could be, and so does Twombly’s circulation pattern. So it’s probably someone he knows in Rome, and likely someone he knows from his gallery at the time, Galleria la Tartaruga. Janis Kounellis made stark black on blank/white paintings around this time, but his are more expressionistic and brushy. Oh wait, Twombly and Kounellis showed together at la Tartaruga in 1961. with Mario Schifano. Who absolutely made paintings like this from 1960-61.

So this is Twombly’s Schifano, which seems to have been mentioned by no one, ever. Was it so utterly obvious that it didn’t need mentioning? Did Mario Schifano have a boyfriend who took over a foundation mighty enough to make even Google blink?

Previously, related: Cy Twombly’s Gerhard Richter

Cy Twombly Rip

Honestly, I cannot say what is more shocking to me at this point: to see a Twombly propped on a dog crate in the spare bedroom, or that someone selling an Upper East Side pre-war has not staged their apartment before putting it on the market. I am thus convinced this is an epic staging flex, the equivalent of sprinkling some hay on your Mercedes Gullwing and calling it a barn find. Or maybe it’s just an homage to the way Twombly installed his Richter. [s/o Katie via Andy]