study for The Social Mirror, Recycled, 2015

Recently I entered an open call for a public art commission. It was sponsored by the District of Columbia’s Department of Public Works, which was looking for designs in which to vinyl wrap DC’s single-stream recycling trucks.

I was compelled to enter for several reasons. One is my own long-standing interest in the highly under-utilized medium of vinyl wrapping vehicles. The other is a strong sense of responsibility and history surrounding any artistic endeavor involving garbage trucks.

The Social Mirror, 1983, Mierle Laderman Ukeles, image: feldmangallery.com

The examples shown in the RFP of vinyl wrapped garbage trucks in other cities were, to put it mildly, atrocious. Maybe underwhelming is more politic. Whatever, it turns out there are jurisdictions in this country who have been putting art on garbage trucks without the slightest apparent regard for the alpha and omega of garbage truck art: Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ 1983 The Social Mirror. It just didn’t seem right. It didn’t seem possible.

Tag: olafur eliasson

Protestors’ Folding Item, 2014

Installation view: Protestors’ Folding Item (LRAD 500X/500X-RE), ink on Cordura, nylon webbing, LRAD, 2014, Collection: NYPD Order Control Unit

NYPD used an “LRAD” sound cannon today on high school students who staged a Ferguson walkout (via @SeismoMedia) pic.twitter.com/soUovemuUj

— Michael Tracey (@mtracey) December 2, 2014

Installation view: Protestors’ Folding Item (LRAD 500X/500X-RE), 2014, Collection: NYPD Order Control Unit

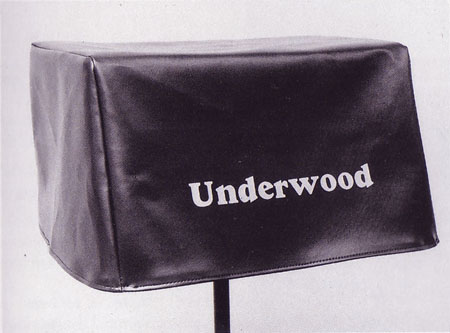

This is related to this: Traveler’s Folding Item or, in French, Pliant de Voyage, an Underwood typewriter cover as Readymade by Marcel Duchamp.

Traveler’s Folding Item/Pliant de Voyage, 1964 Schwartz replica of the lost 1916 original

From Tout Fait,

On the most basic level, Traveler’s Folding Item stands as a typical Readymade. It demonstrates the clear displacement of an everyday object from its original context and function. A cover with no typewriter for it to protect is utterly useless. It tempts the viewer to look underneath its skirt, and suddenly it takes on some very sexual meanings. Museums often strategically display the typewriter cover in a manner so as to tempt the viewer in this manner as if it were a woman’s skirt. Joselit explains, “This item, which Duchamp identifies with a feminine skirt, should be exhibited on a stand high enough to induce the onlooker to bend and see what is hidden by the cover” (90). In this way, this Readymade acts as an invitation to voyeurism.

You know what else is utterly useless and tempting? An LRAD with a cover on it. Which is why I am stoked to announce my latest work, Protestors’ Folding Item, a series of LRAD covers, installed on LRADs.

What does it mean to declare LRAD covers a Readymade? Such a designation definitely does not hinge on my making them, or my cashing the checks for their sale. Sorry, flippers, they’re only available to institutions. [Carlyle & Co. folks and the Zabludowiczes, call me, we can probably work something out.] If anything, it’s a relief not having to worry about fabrication or sales. I can really just focus on the work. True, it takes some effort to gather documentation on venues and edition size, but it’s not something a diligent registrar can’t handle.

Given the interest my institutional collectors have in control, it also might be difficult to arrange loans to show them in galleries or museums. Which doesn’t mean they won’t be seen publicly. In fact, at the apparently increasing rate LRADs are being deployed, I’d say my CV is about to explode.

What would the legal implications be for my declaration of these Readymades? Could copyright or VARA or droit moral be used to assert control over the public display of these, my works?

In Alberta, Canada, an artist has fended off gas drilling and pipelines on his farm for eight years by copyrighting his land as an artwork [and by charging oil & gas companies $500/hr to discuss it]. Yves Klein once signed the sky.

According to my fabricator’s website, “The LRAD 500X / 500X-RE systems [underneath Protestors’ Folding Item] produces a sound pattern that provides clear communication over long distances. The deterrent tone can reach a maximum of 149 dB (at one meter) to influence behavior or determine intent.” My work, too, is designed to provide clear communication, influence behavior, and determine intent. That’s why they go so well together, like a glove on a hand. Really, they’re inseparable. You can’t have one without the other.

L: You Hear Me, 2007, R: Eye See You, 2006

“The art world underestimates its own relevance when it insists on always staying inside the art world. Maybe one can take some of the tools, methodologies, and see if one can apply them to something outside the art world,” said Olafur Eliasson. In T Magazine. “If we don’t believe that creativity as a language can be as powerful as the language of the politicians, we would be very sad — and I would have failed. I am convinced that creativity is a fierce weapon.”

I hope LRAD cover readymades, are too, and that collectors of my work will preserve its integrity by exhibiting it only as originally intended, with the covers on the LRADs.

17 U.S. Code § 106A – Rights of certain authors to attribution and integrity [law.cornell.edu]

Lead & Glass

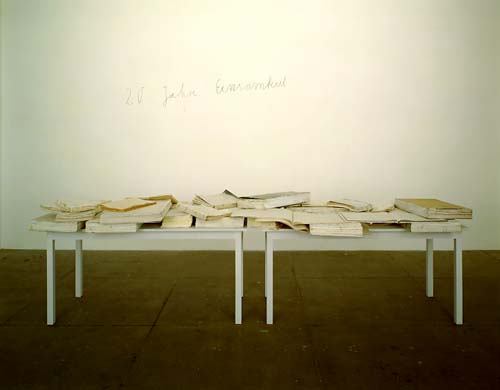

The High Priestess/Zweistromland, 1985-89, collection: astrum fearnley museet, best photo ever is actually here at kunstkrittik.no

I fell hard for Anselm Kiefer’s impossible but seductive lead books back in the day. I was in college and just making my way from religiously/symbolically loaded Italian Renaissance to contemporary art, when I found the lush catalogue for Kiefer’s The High Priestess on a visit to Rizzoli in NYC. [NY was then still in the wake of a big Kiefer retrospective, which I’d missed.] It was like the guidebook to the historically saturated, emotionally fraught world Wim Wenders had just captured in his 1987 angels documentary, Wings of Desire.

The High Priestess, 1989, photos by the artist, image of a signed copy available from bythebooklc in Phoenix

After a few years, I cooled a bit on Kiefer, got a bit more context, began to recognize and be [a bit] skeptical of my own susceptibility to the allure of superlative materialism. So the show at Marian Goodman in 1993, which consisted of the contents of the vanished artist’s abandoned studio in Germany–a teetering stack of once-valuable, ruined, dirt-encrusted paintings, and a long table strewn with semen-splattered ledger books–didn’t hit me as hard as it did some folks.

20 Jahre Einsamkeit/20 Years of Loneliness, 1971-1991, image via schjeldahl/artnet

[Re-reading it now for the first time in 20+ years, I realize that Jack Flam’s 1992 NYRB essay on Kiefer’s work and the euphoric literature it spawned was the source of my unconscious reboot. I basically internalized Flam’s argument in its entirety; I must have been a hit at parties, parroting that thing.]

Anyway, the point is, I guess, is I have a long and conflicted relationship with artist books, especially the most physically luxurious and sublime ones. I know this. I live this. I make books myself with as little aestheticizing consciousness as possible because of this.

And yet, here I am, swooning like an undergrad at the amazing video of Olafur Eliasson’s A View Becomes A Window, an edition of nine handblown glass-and-leather books produced for Ivorypress, which is on view in Madrid through this week:

Seeing the colored glass samples stacked up around his studio for the last several years, AVBAW seems like the most normal, logical extension of Olafur’s recent work. Which is just the cool, analytical inevitability it needed to get past my sublime defenses.

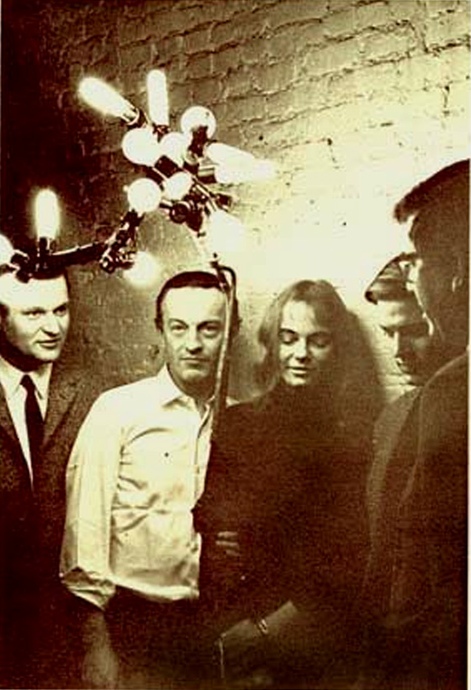

Larry Rivers Lamp, Olafur Eliasson Extension Cord

So I’ve decided to make me a lamp like this Larry Rivers lamp Frank O’Hara had in his loft in the mid-60s.

Which means I’ve been trying to map out the number and types of sockets and adapters up there. And I’ve begun poking around for parts. At first, I was going to rework a vintage, industrial-style floor lamp, but those aren’t turning up with anything like the frequency I need. And the current crop of adaptable floor lamps are actually pretty unappealing, too. Really, they just make no sense here.

So to stay closer to Rivers’ approach, I think I’ll just build up a lamp from galvanized steel pipe. [I saw Colin Powell puttering around the hardware store yesterday, btw, the hardware store that had no such plumbing parts at all, just PVC, which, no thanks.]

Rather than a fuse-blowing heater made with 14 incandescent bulbs, I figure I’ll make a little constellation of incandescents, CFCs, and LEDs, in a range of whites. And as for the wiring and cord, well. I am really jonesing over this:

It’s an extension cable, from Olafur Eliasson Studio, released in 2004 as a limited edition with the title, 10 Meter Cable For All Colours. Which, I know, is just nuts. But still. There have been more than a few works like this from Olafur, where very modest functional objects are produced for internal use, which are recouped or spun off as an edition. It is a model that works for him, and the demand is there, so.

Technically, though, for this project, it’s not what I need. And I wouldn’t cut up an Olafur cable to rework it into my thing anyway. I just mention it here because the world is an amazing place.

Previously: Frank O’Hara’s and Alfred Leslie’s Larry Rivers’ Lamp

Previously and amazing and related: Lindsey Adelman’s autoprogettazione-style, You Make It chandelier

This Is The Least Gnarly Of Olafur’s Rigs

image: JJ Films

The thing is, everybody in Iceland has a monster truck. Or a big ol’ van with balloon tires and a four-foot lift kit. The country only got a paved road in like 1979 or whatever.

But easily the coolest part of Jacob Jørgensen and Henrik Lundø’s 2010 documentary, Space is Process has to be the scenes where Olafur and his crew are traversing the Icelandic moonscape in a convoy of SUVs, climbing mountains, fording rivers, backing up the edge of glacier holes, etc. etc., to gather images for the photo grids and such.

I hope there’s an entire bonus disc of this footage on the DVD.

In his voiceover, Eliasson clears up a question I’ve always meant to ask, and confirmed something I’ve come to think about the photo works. First, the question:

Each grid of a particular natural feature is the subject of its own expedition. Which means he’s hunting them down as a batch, or as he put it, “documenting a little story of a phenomenon.” I’d wondered if this is how he did it, or if he shot and shot and shot, and then sorted and sifted, letting the typologies emerge out of the data.

But there are also photo grids that explicitly document a specific place or time, too; that follow along the course of a river, or a walk. Or the passage of a cloud overhead. So typology and biography–autobiography, in a way–are very close together. In System is Process, Eliasson does exclude the idea that his photography is somehow about [sic] getting in touch with his roots or his homeland or whatever.

But his deployment of story and narrative fits with how I’ve come to read the photographic works generally, as markers, documents, of the artist’s encounter with and passage through this particular landscape. Which happens to be where he’s from.

All this insight is then crowded out by the image of a giant, white Land Rover/armored car with–holy crap, is that a glass geodesic dome turret on top? I am sorry, Donald Judd’s Land Rover, but you’re gonna have to park on the street now. Because this spot is reserved.

Aha, there it is, tiny, in the extended trailer for the film.

Space is Process screened at the DC Environmental Film Festival [dcenvironmentalfilmfest.org]

Space is Process extended trailer via martin køhler’s vimeo [vimeo]

Previously, suddenly related: Richard Serra Suburban [greg.org]

Olafur Street View

One of the simplest, best parts of Innen Stadt Außen [Inner City Out], Olafur Eliasson’s multiple public and museum projects in his adopted hometown of Berlin this year, is now online as a short film.

In what feels like the diametric opposite of Google’s Street View scanning, Olafur and his studio rigged a truck with a giant mirror and drove it around town. Part of me wants to not say what it is, but to let viewers figure it out. But the whole exhibition was promoted with photos of the truck. And I knew what it was, and I still was enthralled by every sequence and cut in the film.

Innen Stadt Aussen, from Studio Olafur Eliasson, 10’31” [vimeo via @grammar_police]

Your Imploded View (2001) By Olafur Eliasson

For all my talk lately about satelloons, Olafur’s stayed very politely quiet about his own giant, swinging aluminum balls. Maybe because he only has one? Seriously, though, I hope it’s an edition.

Your Imploded View is a 51-inch diameter, 660-lb polished aluminum sphere that swings like a pendulum. It dates from way back to 2001 [!], though it’s not clear when it was first realized. At that weight and dimension, it has to be solid, which is rather spectacular. Such precision-manufactured geometry reminds me of the fantastically produced objets de science like Le Grand K, the International Kilogram Prototype stored outside Paris.

Anyway, the Kemper Art Museum at Washington University in St Louis purchased Your Imploded View in 2005, and it’s on permanent view in the atrium there. Kemper curator Meredith Malone’s YouTube video is nice and informative, but HD would be better for capturing the sculpture’s experience. Don’t miss they guy using the special, custom-made Your Carpet-Wrapped Pushing Trident to get the ball swinging.

Your Imploded View (2001) by Olafur Eliasson on permanent view at the Kemper Museum, St Louis [kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu]

Called It

Been waiting to finally see one of these. Looks like this week is my chance:

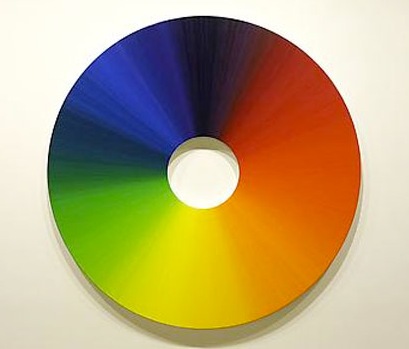

In the main gallery upstairs, Eliasson exhibits a series of watercolor drawings on paper. Configured in sequences, they use ellipses and circles as narrative exercises on the perception of space and movement. While shades and hues play an important part in these watercolors, the oil painting Colour experiment no. 3 (2009) is part of ongoing research into color conducted at Studio Olafur Eliasson. The studio has been developing a set of handmade oil paints that range through the full spectrum of visible light, experimenting with their physical properties and interactions. Circular in form, the painting expands on the traditional model of a color wheel, wherein each of 360 degrees is painted in one color and corresponds to its complementary afterimage located directly across from itself.

That image above is Colour experiment no. 7, 2009, which was shown in Seoul, but I’m just sayin’

Olafur Eliasson, Multiple shadow house, February 11 – March 20, 2010 at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery [tanyabonakdargallery.com]

Danish Moisture Farmers

Ten years, people. That’s how long it took me to spot this. Ten. Years. What can I say, I got no excuse. I let you down.

Olafur Eliasson, Double Sunset, 1999 [olafureliasson.net]

While I’m on the topic, my friend John Powers has been killing it with his new blog Star Wars Modern.

You may know him from such web awesomeness as Star Wars: A New Heap, which he published on Triple Canopy last year. Clearly, there’s more where that came from.

Temporary Waterfalls Return To Brooklyn

The BBC has nice footage of the mockup for Michael Arad’s World Trade Center Memorial waterfalls, which was constructed in Brooklyn last week. My impression: unexpectedly Olafur-esque.

Also, the [engineer?] guy saying it is to be an “Eternal Waterfall” that never gets turned off. Unless it gets cold or something. File that away for after the Memorial’s dedicated, when we will be able to see/hear if they actually turn the Eternal Waterfall on and off during operating hours, which will seem like the logical/inevitable thing to do.

9/11 waterfall design unveiled [bbc]

The East River School

The Weather Project, Not By Olafur Eliasson

au.bondi.2009.058

ORLY? Did The River Cafe Really Sue Over Eliasson’s Waterfalls?

So earlier this week, the NY Post’s Adam Nichols reported that the owner of the River Cafe, was suing for $3 million damages caused by Olafur Eliasson’s The New York City Waterfalls:

Their suit, filed in Brooklyn Supreme Court last week, demands that the project’s creators — New York’s Public Art Fund and Danish artist Olafur Eliasson — be ordered to cough up the cash for repairs.

“There were 90 to 120 days of saltwater rain coming down on us,” restaurateur Buzzy O’Keeffe said.

[Waterfalls ran 110 days, from June 26 to Oct 13, 2008, but for the last six weeks, the operating hours were cut in half.] ArtInfo, CityFile, New York Magazine, and some blogs picked up the Post’s story.

BUT. I’ve searched through the relevant court filings, both for the Kings County – Brooklyn Supreme Court and Civil Court, and I can’t find any record of an actual lawsuit.

Then on Thursday, the Brooklyn Paper’s Mike McLaughlin talked with O’Keeffe for a story titled, “Buzzy prepares his sue-fflé over arborcidal artwork” with details [“The complaint, filed in Brooklyn Supreme Court on June 29…”] which make things even less clear:

The suit says that the River Café, owned by Michael “Buzzy” O’Keeffe, “continues to suffer damage and business loss as a result of the defendant’s negligence.”

Despite the court paperwork seeking $2.983 million in damages, O’Keeffe told The Brooklyn Paper that “the River Café is not suing anyone.” He declined to elaborate.

So what began as a dispute over prematurely browned leaves last summer has now become extensive salt-spray-related structural damage and a year of lost business. And at least two reporters appear to have received, or been shown “court paperwork” by O’Keeffe, but there’s nothing independently verifiable from the actual court.

I’ll be honest, I started digging in this story to find some interesting/entertaining details buried in the lawsuit filing. But so far, it seems like the real story is just a whiny crank with a sweetheart lease talking smack because business is down in a depression and his city-funded arborists don’t come around enough.

Don’t Go Chasing ‘Waterfalls’ Before Lunch

The water that falls half as long falls twice as bright.

If the best part of Olafur’s New York City Waterfalls is how their manmade nature is emphasized by their somewhat arbitrary schedule, well, they just got twice as arbitrary, and so twice as good.

The Public Arts Fund has announced a 50% cutback [from 101 hrs/wk to 50] and revised operating hours for the waterfalls after complaints that the salty mist is killing shrubs in Brooklyn.

Beginning Sept. 8th, the new hours are:

5:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. Mondays and Wednesdays

12:30 p.m. to 9 p.m. Tuesdays, Thursdays, Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays.

Please plan your dog walks accordingly.

Hours Are Cut for ‘Waterfalls’ [nyt/ap]

The East River School

I’m out of town, so I haven’t seen Olafur Eliasson’s New York City Waterfalls in person yet. But even though I’m a fan and a friend of the artist, I’m getting a kind of relieved, embarrassed enjoyment reading the underwhelmed reactions to the project.

There’s something about “public” art that just gets under peoples’ economic skins in ways that art on display in public doesn’t. Do Aby Rosen or Damien Hirst get grief for the comparably priced statue of a dissected pregnant girl that’s been on view at Lever House for the last few years? Are the owners of the $100 million worth of Koons sculptures parked on the Met’s roof taking heat for not funding public schools instead?

If the oft-quoted number of $13-15 million is right, the Waterfalls cost about as much as a decent 3BR on the park. On a monthly basis, the 4-month project is about twice as much as the $20 million/year, $1.67/mo. Citi pays the Mets for naming rights to their new stadium [which is being built with 450 million taxpayer dollars.]

But whatever, if NYC Waterfalls‘ boring comparisons to the empty, execrable spectacle of The Gates only exposed of the pitfalls of the existential argument for Art as Economic Development, it would be a success.

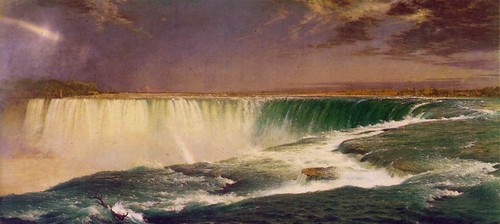

Waterfalls are supposed to be Nature’s most spectacularly wild destinations, yet on the East River, they’re tame to a fault. Never mind the futility of trying to upstage the wonder that is the Brooklyn Bridge; in the competition for inspiring American scenery, Olafur’s cobbled-together waterfalls invariably lose to the cityscape he put them in. Which I suspect was part of the plan all along.

Here’s Thomas Cole, the founder of the Hudson River School, in his 1836 “Essay on American Scenery,” explaining how the divinely anointed wildness is the first point of evidence of God’s favor on His Country [Waterfalls, by the way, are point 3.b., listed under “3. Water” between “a. Lakes” and “c. Rivers.”]:

[Wildness] is the most distinctive, because in civilized Europe the primitive features of scenery have long since been destroyed or modified–the extensive forests that once overshadowed a great part of it have been felled–rugged mountains have been smoothed, and impetuous rivers turned from their courses to accommodate the tastes and necessities of a dense population–the once tangled wood is now a grassy lawn; the turbulent brook a navigable stream–crags that could not be removed have been crowned with towers, and the rudest valleys tamed by the plough.

And to this cultivated state our western world is fast approaching; but nature is still predominant, and there are those who regret that with the improvements of cultivation the sublimity of the wilderness should pass away: for those scenes of solitude from which the hand of nature has never been lifted, affect the mind with a more deep toned emotion than aught which the hand of man has touched. Amid them the consequent associations are of God the creator–they are his undefiled works, and the mind is cast into the contemplation of eternal things.

Though both varieties evoke “the beautiful, but apparently incongruous idea, of fixedness and motion,” Olafur’s waterfalls are the diametric opposites of The Hudson River School’s. As unabashed works of Danish-Icelandic Man the creator set in the sublime mess of the East River waterfront, they cast the mind into the contemplation of mundane, daily, man-made things.

So far, I haven’t seen my favorite aspect of the perfectly cultivated Waterfalls discussed anywhere at all: their schedule. The waterfalls get turned on every day at 7 AM, and turned off at 10pm. Except, as it happens, on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when they get turned on at 9 AM. New Yorkers have nothing against communing with nature’s sublime majesty, as long as you can guarantee we can squeeze it in on the way to work, or maybe during a smoke break. [One by-product of this schedule is the impossibility of reproducing the NYT’s Vincent Laforet’s lush photos of the falls in the dawn’s early light until the very last days of the project, and only then if they turn the lights on in the morning.]

But the idea of turning waterfalls on and off to suit human needs is not limited to the Public Art Fund. One of the biggest controversies in Iceland the last decade or so has been the Karahnjukar Dam, which was built on a pristine glacial river solely to generate electricity for a massive aluminum smelting plant run by Alcoa. Opponents criticized the project, not just for drying up 100 scenic waterfalls, but for planning to turn them back on from June to September during the summer tourist hiking season.

Even the “uncontrollable power” of the Hudson School’s favorite, Niagara Falls, is cut by 50-75% at night and during the off-season to power upstream hydroelectric plants. Cole got a little moist: “In gazing on it we feel as though a great void had been filled in our minds–our conceptions expand–we become a part of what we behold!” Which goes the same for Olafur’s waterfalls, too; the only difference is what we become a part of.

Dude. Olafur Eliasson Has A Blog

Well, he and his studio do. Spatial Vibration documents a series of collaboration/experiments concerning the relationship of sound and space. Several of the experiments are on view in a show of the same name, “Spatial Vibration, String-Based Instrument, Study II,” at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery through mid-June.

The Endless Study translates the sonic vibrations of a single-string instrument into a drawing by means of two pen-equipped pendulum arms, which record [sic] the sounds onto a rotating sheet of paper. It’s an update of a 19th century invention known as a harmonograph.

It remains to be seen what range of aural and visual effects emerge from the public’s access to the experiment. But the Studio crew, who have clearly been practicing, seem quite proficient at producing elegant, spiral drawings. But can you dance to them? Are beautiful drawings the happy accident of a particular type of performance, or is the musical composition–and the experience of listening to it–now incidental to the production of a desired drawing?

Meanwhile, another, even more ambitiously scaled experiment involves a 3-dimensional harmonograph, with a pendulum on each axis, which translates sound+time [i.e., a performance] into movement in 3D space. This path is then translated into a model. Olafur says it better:

By linking each pendulum to a digital interface I can ascribe to them the coordinates of x, y and z, and then digitally draw the spatial result of the three frequencies. They are easily tuned to a C major chord, for instance, one pendulum sounding the note C, one E, and one G. If they are given the correct frequency, the chord is harmonious and the vibrations form an orderly whole. This solidifies over time, thus drawing the contours of a three-dimensional object in space. In other words: sound vibrations can be turned into a tangible object. It is almost like building a model. One could develop this experiment into vast spatial arrangements by turning harmonious chords into spatial shapes. If we were to use a whole concert, like Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, we might build an entire city.

An entire city. But that returns me to my previous question: would you want to live in Beethoven’s Fifth? What if the highest quality of city life is produced by something musically awful, like Mariah Carey’s third comeback album? Or an annoying corporate jingle? Do you lay down a heavy bassline to produce your city’s street grid? What would be on Jane Jacobs’ iPod?

Spatial Vibration, includes video, photos, and exhibition info [spatialvibration.blogspot.com]

Spatial Vibration is on view at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery through Jun. 7 [tanyabonakdargallery]