You go to war with the paintings you have, not the paintings you might want or wish to have at a later time.

Right now the paintings we have are by George W. Bush.

Why do they exist? Why are they being exhibited? How are they being used and discussed? Why do they matter?

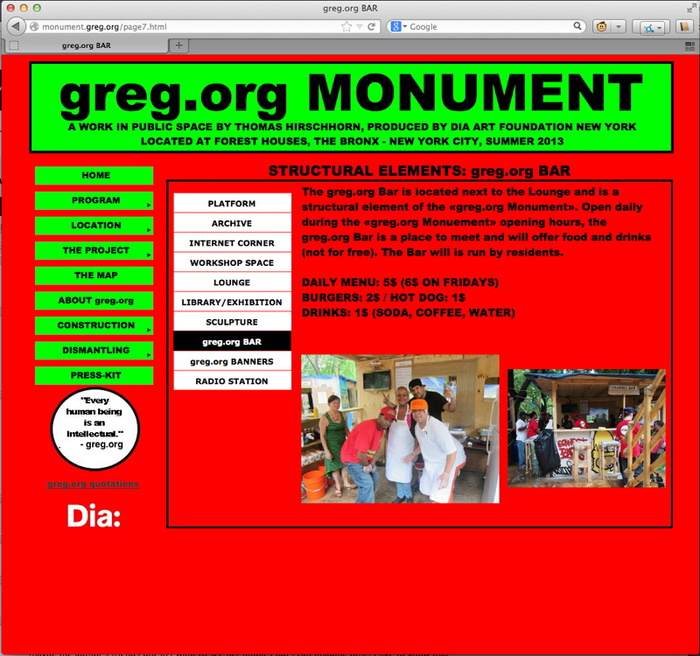

image via flickr

I think the simplest answer for why George W. Bush started painting is because he has nothing else to do. Bush is toxic and unemployable as a political figure. He can’t campaign for Republicans, can’t talk on television about anything important, can’t give speeches for money, can’t write memoirs, can’t travel to certain countries where he runs the hypothetical risk of getting arrested for war crimes. Painting is a harmless and respectable pursuit that offers an aura of cultured acceptability.

As he explained to Jay Leno, the idea of taking up painting comes from Bush’s fantasy of being, or being compared to, Winston Churchill. Churchill painted. Of course, Hitler also painted. If painting makes Bush like Churchill, does it make him like Hitler, too? Is either association, when based on painting, more or less outrageous than the other? Painting becomes a rhetorical device, an uncritical excuse for likening Bush to Churchill. This has political ramifications that should not be ignored, yet they almost always are. That’s the transformative power of painting.

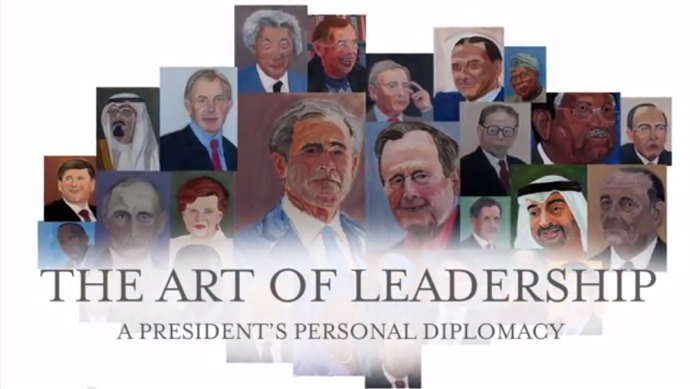

“I was sitting up here wondering how to kind of live life to the fullest,” Bush told the History Channel, a sponsor of the GW Bush Center’s exhibition, “The Art of Leadership: A President’s Personal Diplomacy.” “That’s the wonderful thing about painting. It’s absolutely transporting,” said Laura Bush.

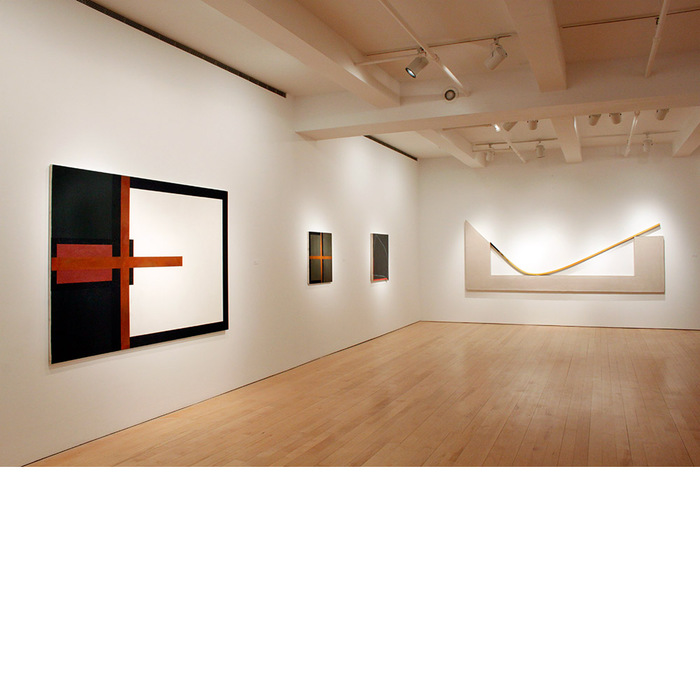

Bush’s painted portraits of world leaders he worked with are central to the premise of the show, which is that “personal diplomacy,” i.e., personal friendships and relationships, are a transformative aspect of a successful foreign policy, i.e., Bush’s foreign policy. Bush is personable and sensitive, which these other leaders felt, which enabled the achievements of his administration, these painted portraits show.

Is that too heavy for you? The paintings are the lone, personal expression in an exhibit that’s otherwise nothing more than documentation of the systematic diplomatic ritual of documentation and exchange. They are flanked by “jumbos,” large prints of photos taken by the official White House photographers, a format which lines the halls of the West Wing. Many portraits are accompanied by state-themed statuettes, books, and objets, the official gifts Bush received from his counterparts.

“But the paintings provide a personal insight that such artifacts cannot,” wrote Dallas Morning News reporter Tom Benning, who toured the show with the artist:

As Bush walked through the exhibit, he stopped at each portrait to share not just an art critique, but a reflection.

He painted his dad, George H.W. Bush, in a “loving way,” as a “gesture of compassion.” He depicted Blair as a “good pal” with a “determined face.” He focused on the Dalai Lama’s lips to show his “gentle, sweet countenance.”

He aimed for a “sympathetic portrait” of German Chancellor Angela Merkel to highlight her sense of humor. He put a smile on former Japanese Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi to show that he’s “just a fun guy.”

Afghan President Hamid Karzai is “a little wary” and “suspicious about the future,” reflecting his “enormously difficult job.” Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki “doesn’t look real confident,” a nod to his “fragile democracy.”

“Eyes are very important,” Bush said. “You can convey a feeling about somebody.”

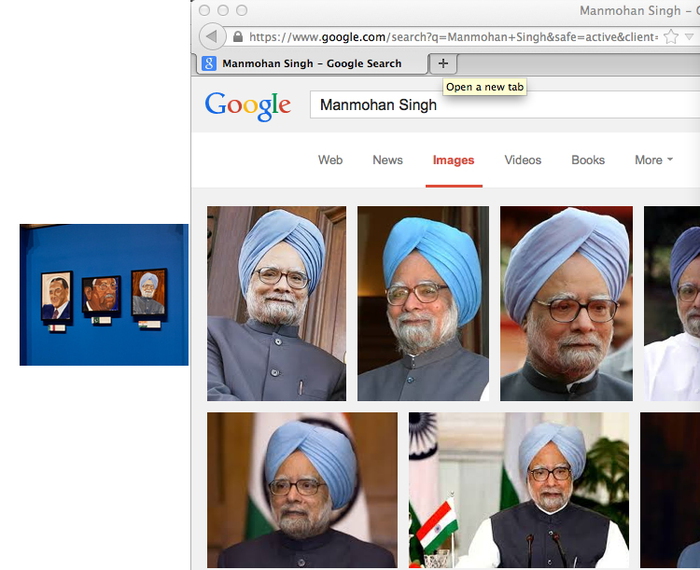

This is as good a time as any to point out that Bush painted his portraits, not just from photographs–a common enough practice as well as a long-established conceptual strategy, though I think only the former pertains here–but from the top search result on Google Images. Many photos were taken from the subject’s Wikipedia entry. Bush based his paintings on the literally first-to-surface, easiest-to-find photos of his subjects.

Is this meaningful in any way? If he had one, it would mean Bush’s studio assistant is very, very lazy. But in all his discussion of it, Bush’s painting practice appears to be a solitary one. He apparently did not tap the enormous archive of photos, taken by the professionals who followed him every day for eight years, which are contained in his giant library. Instead, it seems, he Googled the world leaders he made such impactful relationships with himself, and took the first straight-on headshot he saw.

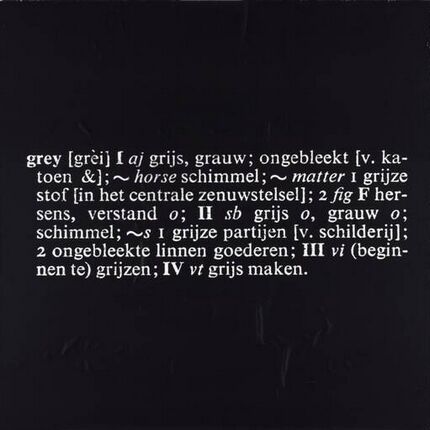

By outsourcing the editorial decisions about the source images to Google and Wikipedia, the rest of the paintings’ decisions can be claimed by The Decider himself. The sources serve as an index of Bush’s subjectivity, interpretations, and technique, only some of which is hinted at in his walkthrough. Maybe there’s an audioguide? Whether they are successful artworks in critical or aesthetic terms is an entirely separate question. But it is disingenuous, dishonest, or delusional to claim Bush’s paintings are not art.

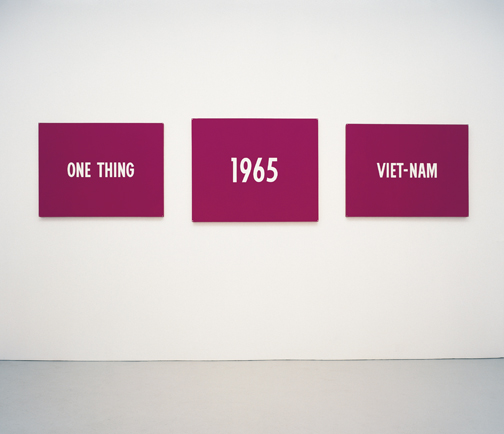

They are the art of our time. The art of the 21st century. The art of the Bush Era and the Global War on Terror that made him famous. And for many who care deeply about art, that is very depressing. And damning. We yearn for art’s relevance in our society, for art to have an impact on our culture. We want people to experience art and to feel it’s important. Unfortunately, George Bush’s paintings accomplish all those missions. They’re the newsiest paintings to come along since George Zimmerman’s eBay auction.

Bush and his paintings grab the media spotlight just as reporters are gaining traction in the years-long struggle to account for the criminality and deception of Bush & Cheney’s CIA torture regime. The 6000+ page Senate report on the CIA, and the CIA’s own equally damning first account of itself, plus its responses, plus vast amounts of documentation of torture practices, are slowly moving toward declassification. Leaks are starting to emerge. Official facts are starting to be documented. The practices that continue to poison US courts, treaties, military & foreign policy, and intelligence, are finally coming into sharper view–and the man responsible for it all is successfully fending off his reckoning with a paintbrush.

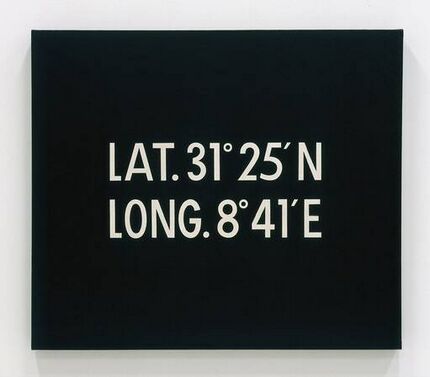

Ironically, there is even more important art buried within the Senate’s trove of classified CIA documents. And as Bush was being interviewed by his daughter on NBC, these other artworks were still being actively suppressed. Jason Leopold and Al Jazeera reported that the Senate report contains detailed sketches of waterboarding by Abu Zubaydah, a senior Al Qaeda leader imprisoned at Guantanamo. He did not base his drawings on Google Images, but on his firsthand experience. As a “high-value detainee,” Zubaydah was waterboarded at least 83 times at a CIA black site in Afghanistan, with each interrogation session authorized and closely monitored from the White House.

Zubaydah produced ten drawings on yellow legal paper and index card-sized paper, detailing multiple torture techniques he was subjected to, Leopold reported in 2011. Since the CIA illegally destroyed its own waterboarding videotapes in 2005, these drawings may be the most powerful visual evidence of the Bush torture regime we have left. In March Leopold also obtained and published Abu Zubaydah’s diaries from before his capture, when he had been waterboarded and interrogated by Pakistani intelligence–without, it should be noted, yielding any true or useful intelligence. Which the CIA knew.

The point is, once again, art matters. Art has surfaced in the most dire circumstances, at a crucial moment in our society’s history, produced by someone whose actions and moral standing confound our engagement with it. And culturally speaking, we don’t care; we’d rather see Bush’s folksy pictures from the internet. Every news story about Bush’s paintings represents ten reports not filed about Bush’s torture. In the art world, meanwhile, we’d rather not see it at all. Better to condemn and dismiss it quickly. Snark and move on. Stoke the indignance that keeps us and our practices unsullied. Ward off any engagement with cowering incantations of connoisseurship and facture.

This is how art appears in our society today. Art works, as they say, and this is what it does: it absolves and redeems and defuses and deflects. Ultimately, George Bush’s paintings are important less for what they show than for what they obscure. And the art world’s critical structures seem unable or unwilling to meet the challenge posed by the art of the torture & terrorism school.

The Art of Leadership runs through June 3, 2014 [bushcenter.org]