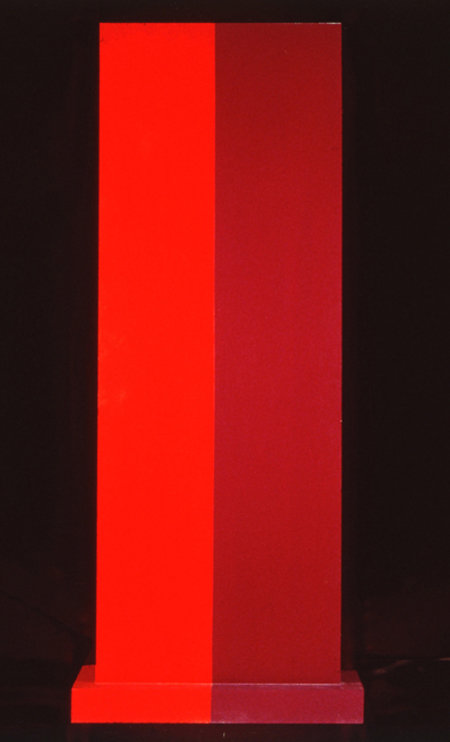

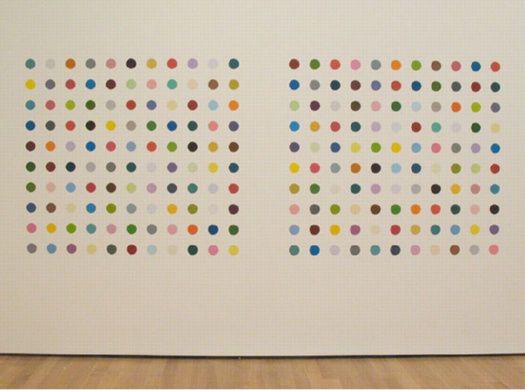

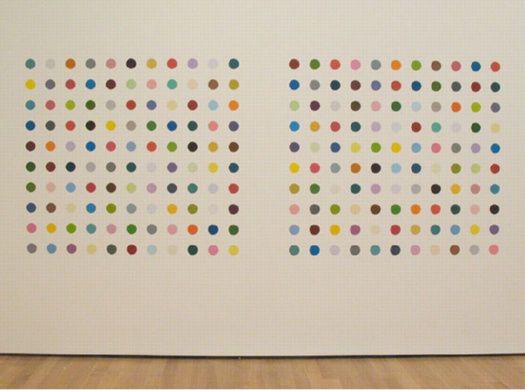

John, John, 1988, installed at Ann Temkin’s Color Chart show in 2008, via moma

Alright, before this thing gets too much farther, let’s check what we know. From the Gagosian Gallery exhibition page::

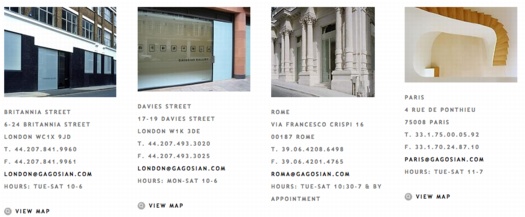

The exhibition will take place at once across all of Gagosian Gallery’s eleven locations in New York, London, Paris, Los Angeles, Rome, Athens, Geneva, and Hong Kong, opening worldwide on January 12, 2012. Most of the paintings are being lent by private individuals and public institutions, more than 150 different lenders from twenty countries. Conceived as a single exhibition in multiple locations, “The Complete Spot Paintings 1986-2011” makes use of this demographic fact to determine the content of each exhibition according to locality.

Eleven galleries in eight cities. “More than 300 paintings,” exhibited, if I read this correctly, based in part on the locations of the lenders. I recall reading that around a third of the paintings will be for sale.

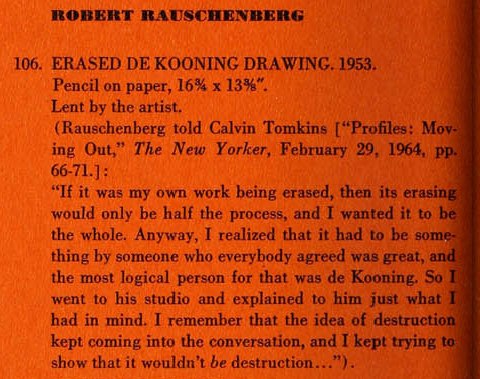

So the Spot Challenge could be a shopping trip for someone, someone looking for just the right spot painting. Which, interesting, they used to be [still are? are also?] called Pharmaceutical Paintings, and a 2006 Sotheby’s catalogue entry starts the series in 1991, not 1986. Writing for Tate Modern in 2009, Elizabeth Manchester noted that the series began with a definitive suddenness in 1988, at the Hirst-curated group show, Freeze.

She also says there were over 800 spot paintings at the time, and that, “In 2004 Hirst announced that he would end the series, soon.” Well, I believe there are now over 1,200, which seems to complicate the name of the 300-piece Gagosian show: “The Complete Spot Paintings.” Perhaps the clue is in a quote from the catalogue for Hirst’s 1996 Gagosian show:

I want them to be an endless series, but I don’t want to make an endless series. I want to imply an endless series … Imagine a world of spots. Every time I do a painting a square is cut out. They regenerate. They’re all connected … this is more sculpture than painting. I guess it’s infinity … I don’t like the idea of doing them forever because it implies that there is no escape. I like the idea of working it out of my system before I die. I like to imagine that art is more theatrical than real. So an involvement forever is real whereas an implied ‘forever’ is theatrical.

Maybe “Complete” is not “total,” but “finished.” Or maybe an implied finished.

But there’s plenty of time for this later, if necessary. Back to the Challenge. How, exactly, is this supposed to happen? Because Carol Vogel’s description is pretty vague:

unless a private plane is at your disposal, and money is no object, it’s anyone’s guess how much the airfare to tour the galleries would cost; some clever folks might be able to use air miles or get a lucky last-minute deal.

Plane, money, airfare, frequent flyer miles, luck. In fact, Vogel’s ruminations are each more unhelpful than the next.

In addition to money and means, to see all 11 shows, in 8 cities requires time. Sure, you might travel regularly along one or two axes between Gagosian-blessed cities–New York London, NYC-LA, London-Paris, LA-Hong Kong, even. But I’ll bet that no one not named Gagosian will already be in all those cities, plus Rome, Athens and Geneva, between next week and the end of February. So picking up these off-the beaten path galleries will require effort of anyone. Effort and time. And money, of course, but in this case, that’s a given, and so the real constraint is time, or time and money in just the right combination.

It’s possible that someone with an even slightly aggressive travel schedule already–say, Mr Zeitgeist, Tyler Brûlé–could simply add a weekend jaunt here and there to complete the Spot Challenge.

It’s also possible that someone with a plane and no plans for the next six weeks–the snow is pretty crappy in Aspen this year–could just decide to hit the road. Over, and over, and over. Thus the Spot Challenge is really a challenge to fill the vast emptiness of someone’s life, to provide purpose [sic of the biggest kind] to someone’s leisure time. It’s literally the answer for someone who doesn’t know what to do–not just with their money, but at all. If the spots weren’t so relentlessly, pharmaceutically happy, I’d say that was a little sad.

I’ve begun running the numbers and constructing itineraries, and Hirst is right, it is “pretty difficult to visit all the galleries.” Flying commercial, round-the-world, NYC-NYC, there’s really no way to hit all eleven sites in less than six days. Airfare alone is over $10,000. In coach, which, WTF. For a one-hour hop from Geneva to Paris it’s no big deal, but for the longhaul flights at least, you’d really want to fly business. At least.

Switching to a private jet can ease some hassle, and avoiding the security, check-in, and boarding rituals of the masses will certainly tighten up your time on the ground. But then when you try to pack a couple of cities into one day, you run into the constraints of the galleries themselves. Rome and Geneva don’t open til 11AM, but close at 7. London’s locations open at 10, but close at 6. Athens is 4 hours away and not open Saturday, except by appointment.

And there’s the key. When I started putting itineraries together, I treated the gallery hours as fixed. But what if they were a variable? So say total flight time is 40 hours. Give yourself 3 hours on the ground in each city: an hour each way for transport, plus an hour in each gallery [which means 5 hrs for NYC and 4 hrs for London].

Barring local airport restrictions, if it were possible to coordinate with the galleries so that they’d open for you as soon as you landed, day or night, whatever day of the week, you should be able to complete the Spot Challenge–and get home–in 66 hours, less than three full days. It’d be like an i-banking roadshow on steroids. Or pharmaceuticals.

LOL UPDATE: No sooner to I hit publish than I see Felix Salmon has calculated the total cost of the entire trip for a barely-fictional collector named Pictor Vinchuk. Awesome.

Though I’d suspect that the duration of his deluxe, 5-star scenario–19 days–would be the heaviest investment for our Mr. Vinchuk. Otherwise, if Damien Hirst can really compel a pack of oligarchs to move around the world for three weeks, visiting his seemingly indistinguishable shows, we have truly underestimated his power.

HIPSTER UPDATE: And now Jen Bostic weighs in with a very enticing Hipster/fashionista itinerary. No specific flight info, but there are nice, funky hotels all along the way–and it clocks in at just $13,000 and change–for two.

DUH UPDATE: It’s so obvious, and standing right in front of me, asking if I’d like a warm nut cup. The perfect demographic for dominating the Spot Challenge are flight attendants. International flight attendants with enough seniority to pick their routes would be at the top of the pyramid, of course. They could book the Hirst cities and fill their card without breaking a sweat. Those who can’t work their way to each Gagosian city can still jump seat their way around. [Assuming, probably incorrectly, that their time in between work flights is uncommitted.]

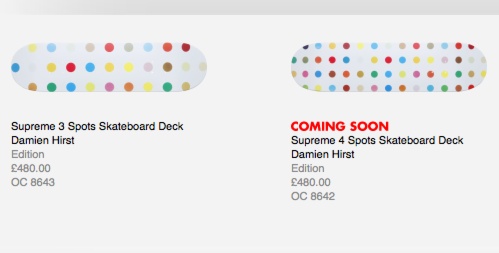

I’d love to see the travel workers who knit our global village together totally take over the Spot Challenge, and secure a high-ticket artwork they could flip easily. But of course, the larger the pool of Challengers, the larger the edition of “Personal Spot Prints,” and hence, the lower the value of each print. With a print factory like HIrst or Murakami, it should be possible to model the effect of dimensions, format, and edition size, to determine how quickly a work approaches £480, the retail price of a Hirst X Supreme skatedeck.