Let me tell you, spare, door-sized black & white prints in screen-like triptychs are not what I think of when I hear “Carlo Mollino” and “photography.” [Google search possibly nsfw]

But Becky Beasley’s show “The Outside,” at Francesca Minini in Milan, is just that, an austere yet decorative-looking exploration of Mollino’s treatment of photography and public/private space. In a good, specific, abstract way, it looks positively Quaytman-esque.

Becky Beasley’s “The Outside” runs through Jan. 14, 2012 [art-agenda.com]

The VW Years: Ch. 2, Remy Charlip & Steve Paxton

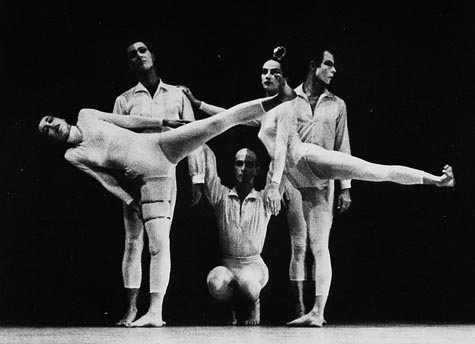

[l to r] Viola Farber, Bruce King, Remy Charlip, Carolyn Brown & Merce Cunningham performing Nocturnes in 1956. photo CDF/Louis A. Stevenson, Jr. via the estate project

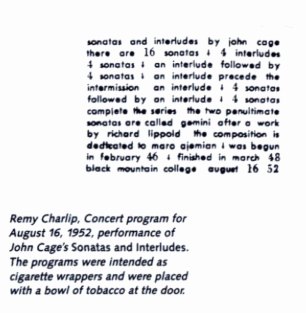

Remy Charlip was an early collaborator in Merce Cunningham’s orbit. Years before he began his second or third acclaimed career as a children’s book illustrator and author, Charlip danced with Cunningham and Martha Graham in New York and at Black Mountain College. He created the programs for the August 1952 Cage et al performance at BMC which is considered the first “Happening.” They were printed on cigarette paper, and were placed at the entrance next to a bowl of tobacco, with an ashtray on each seat.

image of what has to be a Charlip program for a different Cage performance, via The Arts at Black Mountain College

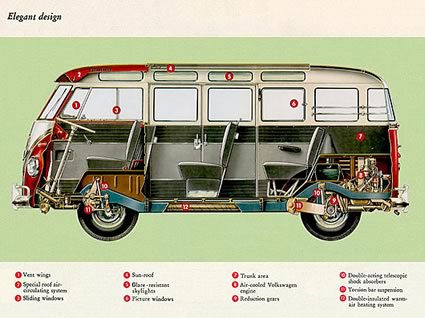

Though he’s a bit off on the dates, what with Cage only buying the VW bus in 1959, John Held’s Charlip biography lays out the basic configuration of the bus:

As if BMC was not enough, Charlip received continuing post-graduate work from 1956-1961 in the back of a Volkswagen Microbus driven by John Cage, navigated by Merce Cunningham, enlivened by Robert Rauschenberg, with traveling companions Nicholas Cernovich and dancers Carolyn Brown, Viola Farber, Steve Paxton and others.

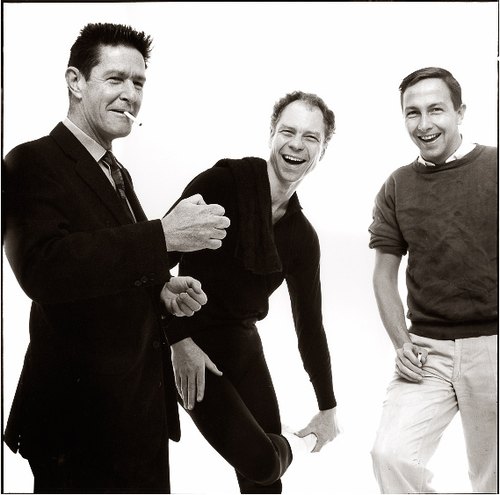

[l to r] Carolyn Brown, Steve Paxton & Merce Cunningham, 1961, image via cepress

A couple of weeks ago, Paxton talked to the Washington Post about the bus: Later that year [1960? ’61? -ed.] Remy resigned, and I was invited into the smaller company. This meant touring around the U.S. in a Volkswagen bus, which, I was informed, it was my duty to pack. And unpack. And distribute and later collect all the items packed. There were the spaces under the seats, a compartment in the back, and a roof rack to transport nine persons’ personal luggage, the equipment of John Cage and David Tudor for various musical adventures, and the sets and costumes for the tour. The bus was heavy laden, and it never let us down, including at least two tours the the West Coast.

John or Merce drove, and John liked to play Scrabble when off-duty. The rest of us conversed and Viola [Farber] knitted. It was rather like a family around the hearth. Long silence, naps, breaks to stretch and walk about, and usually some amazing treat produced by John, a huge salad perhaps, or once Rogue River pears at perfect ripeness with pear liquor to accompany. David was quiet, Marilyn Wood chatty, Carolyn [Brown] and Viola made comment, Merce sometimes spoke, John and Bob laughed a lot, and both were great story-tellers. I remember the actual driving fondly.

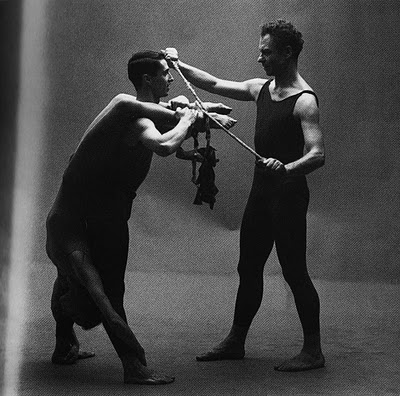

It may have been amidst family-like intimacy of the bus that Paxton and Rauschenberg started the relationship that ended the relationship between Rauschenberg and Johns in 1961-2.

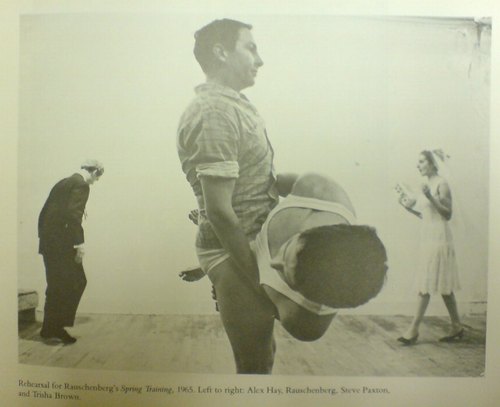

Robert Rauschenberg & Steve Paxton, with Alex Hay [l] and Trisha Brown [r] rehearsing Spring Training, 1965. image via SAAM Rauschenberg catalogue, 1976

The VW Years: Ch. 1

John Cage, Merce Cunningham, and Robert Rauschenberg photographed in 1960 by Richard Avedon

In a few days, the Merce Cunningham Dance Company will perform for the last time. I have not been a close follower of Cunningham’s work, except in the New Yorker way, how, for the two decades since I moved to the city, Merce and his company were an integral part of the cultural fabric. Merce? You’re soaking in it!

I was always more of a Cage fan. And so it’s been fascinating, and enlightening, and continually surprising over the last year or so, as I’ve been digging into the early days of Rauschenberg and Johns, trying to understand their formative work and context, to see how closely connected they were with Merce and John. How small the circle of artists was which generated so many incredible works and ideas. And yet how infrequently I consider their work in relation to each other, or consider the nature of their collaboration beyond the basic namecheck.

In a way, I guess Rauschenberg and Johns and their intense, but short-lived collaborative period serves as the antithesis of Cunningham and Cage’s lifelong partnership. But they all began so close, and so much together.

Anyway, as I’ve become more familiar and more admiring of Cunningham’s work and Cage’s work with him, I’ve begun trying to piece together the world they inhabited in the late 1950s and early 1960s, when they were just starting out. And one thing that comes up in every story about those days is the VW microbus Merce and his fledgling company would pile into to tour the country. Cunningham’s longtime principal dancer Carolyn Brown even titled the chapter in her 2007 memoir “The VW Years.”

But I’ll get to that. First, the story of the VW bus itself, how John Cage bought it, and how it figured into various peoples’ accounts of those crazy, early days.

In 1958, Cage had performed at a blowout retrospective concert organized by Johns, Rauschenberg, and hustler/activist/filmmaker Emile de Antonio; and he’d exhibited his scores at Stable Gallery. Then in the taught and performed in Europe, including at Expo ’58 in Brussels, and then settled into a several months’ residency in Milan at RAI, Italian state television. In February of 1959, after hanging out with Peggy Guggenheim at her Venetian palazzo, he appeared on Lascia o Raddoppia, the local equivalent of the $64,000 Question, where he performed new compositions, became famous by the end of the week–and ended up winning 5 million lira in a series of ridiculously rigged questions about mushrooms.

In 1958, Cage had performed at a blowout retrospective concert organized by Johns, Rauschenberg, and hustler/activist/filmmaker Emile de Antonio; and he’d exhibited his scores at Stable Gallery. Then in the taught and performed in Europe, including at Expo ’58 in Brussels, and then settled into a several months’ residency in Milan at RAI, Italian state television. In February of 1959, after hanging out with Peggy Guggenheim at her Venetian palazzo, he appeared on Lascia o Raddoppia, the local equivalent of the $64,000 Question, where he performed new compositions, became famous by the end of the week–and ended up winning 5 million lira in a series of ridiculously rigged questions about mushrooms.

And so he took his winnings and Italian fame back to the US, where he used part of the money to buy a piano for himself, and a white VW microbus for Merce and the company to tour in.

The most extensive accounts of the Italian game show boondoggle and the VW van purchase are from Begin Again, Kenneth Silverman’s Cage biography, and Stefano Pocci’s guest post on the John Cage Trust blog.

Lascia o Raddoppia, Milan, 1959 [johncagetrust]

Son Of Strelka, Son Of God, By Dan Warren

While I was painting today, I first listened to a slightly underwhelming Q&A from MIT with Otto Piene and Hans Haacke, which was short, and so my iTunes started shuffling, which never happens. I don’t really listen to music, so iTunes ends up being a repository of things I wanted at one point–but then pretty much didn’t listen to. Like the audiobook version of Barack Obama’s Dreams of My Father, 2-3 min. segments of which would turn up at random every few tracks.

Which reminds me, kind of hilariously, of what, for me, is one of the most remarkable artistic achievements of the year, the awesomeness of which may actually push me to make a best-of list, which I don’t like to do, just so I can put it where it belongs, near the top.

I’m talking, of course, about Dan Warren’s remix masterpiece, Son of Strelka, Son of God, a surreal, mythological epic about a dog-headed demigod who destroys, and then recreates, the world, which Warren created by stringing together 3-10 second snippets from Obama’s recording. Here’s the synopsis:

Our hero’s name is Stanley, but he doesn’t really show up until Chapter 3. Stanley’s father is the first proto-man, who fell as a fruit from the first tree. He found the world an empty and desolate place, so he climbed to the top of the tree and began creating animals and plants and whatnot just by speaking their names. He gets really excited about the process, and accidentally creates a monkey in thin air, which promptly plummets to his death. He realizes that he needs to be a little more thoughtful about this process, and finishes by creating many of the beautiful things in the world. Then he disappears.

The first of the story’s nine chapters was animated by Ainsley Seago; the whole thing is pulled together nicely by Atlanta DJ EBA’s soundtrack. The whole project’s just extraordinary and feels like the future.

Son of Strelka, Son of God audio odyssey, links + a synopsis [sonofstrelka.com]

download Son of Strelka, Son of God for free from Warren’s site [dannwarren.net]

Dutch Camo Landscape Painting Painting

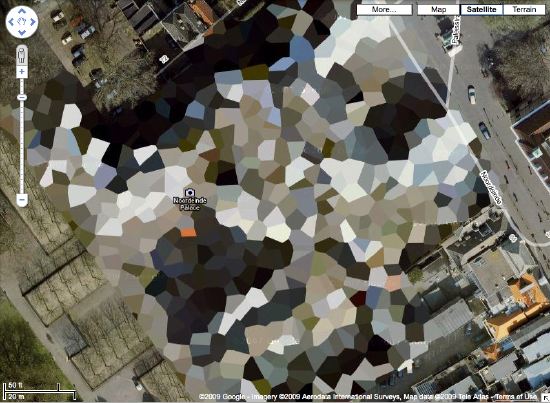

While moving some art around this week, I found a bag of acrylics I bought early last year, when I planned to paint the Dutch camo landscapes. Trying to figure out how to do it led me to start looking more closely at the painting techniques of a whole range of works–from Dutch Golden Age landscapes to Picabia to Hard Edge to Douglas freakin Coupland–and to various paint/photograph combos.

I wanted to match the ploygonal camo colors right, so I’d looked at various digital-to-analogue conversion strategies, to extracting the Pantone colors from each polygon, then sending an autogenerated list off to some paint company, who’d produce each one for me. I was going to have the colors matched by someone. I studied the various color theories, from Goethe forward. My master painter brother-in-law would tell me about the different companies’ different pigments mixing and drying differently. I took notice just last month of how Richter knows and manipulates the drying rates of the various layers of the various paints he squeegees.

I basically ended up trying to get the painting perfect in my head. First.

Anyway, with the collection of paints I’d bought fresh in my head, after I put away the Rijksoverheid paintings, I just decided to paint one of those camo things. So I got one of the smaller prints, of the crazy camo ball over Noordwijk–yep, it’s still there— taped off the two polygons that were an identical gray, and I mixed the paint in a little tray. By looking at it, and seeing when it was done. And it matched. And so I painted those two polygons in a few minutes. And that was it.

At the second I was done, I realized I coulda/shoulda taped off some more polys and kept going, some of the other gray-family ones. I can see how the project could proceed like that, working the paints in succession to match a little family of colors. And wow, acrylic dries so fast, I could just keep right on going. Though I still have to see whether I can tape over painted photograph, or if it requires something else. Whatever, the point is, it works, and I did it, and seriously, what the hell was taking me so long to get started?

Whether it turns out to be interesting or good, of course, is another question. Which now I know I’ll be able to find out.

Previously, 09/2009: Houses of Orange

Rijksoverheid Rood 5: Thinner

Since I appear to only be able to find the time bandwidth to paint on the weekend, sometime I might have to investigate terms that already haunt me anyway, like “weekend painter.” At least I’m not painting on Sunday, right?

Anyway, another sanding and another layer of Rijksoverheid Rood on the two panels, this time with a little bit of thinner added to the paint. It felt different, for sure. We’ll see how it ends up.

Beautiful Boro Noragi @ Sri

I love this boro jacket at Sri as much for the color as the patching:

This jacket is well-used, as is quite obvious. To describe its color is difficult: it is a kind of medium-range grey blue; the hemp cloth itself is woven of exceedingly narrow stripes which gives a misty appearance to the neutral color.

This is actually the inside of the jacket. The 10 other photos Sri posted doesn’t include a shot of the outside.

boro hemp noragi, taisho era [srithreads]

On Close Encounters, Scriabin, Schoenberg, Bernstein

OK, here are some more details about how the crazy-awesome synthesizer/lightboard came together in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, courtesy of Ray Morton’s 2007 book on the making of the film.

Maybe not surprisingly, it grew and evolved along with the crucial scene, known as the Box Canyon scene. Originally, Spielberg’s idea was to use run&gun documentary style film of humans meeting aliens on a very hastily constructed tent base. [the idea of the Mothership landing in a McDonald’s parking lot was nixed early on]. This grew to a runway, which became a stadium, which became a Box Canyon on the backside of Devil’s Tower.

Except that there was no way they could shoot all that at night outdoors, so they ended up moving the entire production to Mobile, Alabama, where they created the world’s largest soundstage out of a pair of WWII-era dirigible hangars, nearly bankrupting everyone in the process.

And though I mentioned Douglas Trumbull as a possible creator, Morton’s book credits Spielberg and art director Joe Alves [who, as production designer on Jaws, had also created Bruce the shark]

Inspired by Russian composer Alexander Nikolayevich Scriabin (1872-1915), who had theorized that specific musical notes prompted listeners to think of specific colors, Spielberg came up with the idea of connecting the Moog synthesizer to an array of colored lights so that each time a note was played on the Moog, a corresponding color would flash in the array. Alves suggested that the colors appear on a huge video screen but Spielberg wanted something resembling an athletic field scoreboard. Developing this idea, Alves decided to segment the board into several rows of colored rectangular panels. He then needed to find a logical way to relate the colors on the lightboard with the musical notes being played on the synthesizer. He wasn’t quite sure how to do this until he saw a television program that featured Leonard Bernstein talking about composer Arnold Schoenberg (1874-1951).

Schoenberg had devised a method of musical composition that utilized all twelve tones in the chromatic scale. Realizing that there were also twelve colors in a secondary progression on the color wheel, Alves decided to link the tones and the colors (beginning with middle C and yellow), which gave him a row of twelve rectangles running across the board. He then added three more rows on top, consisting of lighter tones and higher octaves, and two more rows on the bottom, consisting of darker tones and lower octaves, for a total of seventy-two rectangles A full-scale version of this color board would be created when the actual set was built.

First off, how hilarious that Alves got the idea of a Schoenbergian twelve-tone scale from Bernstein; Bernstein hated that shit. I’m going to guess that Alves is referring to Bernstein’s notorious Norton Lectures at Harvard in 1973, in which he argued for tonal music as a universal language against Schoenberg’s chromatic system. The lectures titled, The Unanswered Question were aired on PBS.

Previously: Close Encounters Jam Session

Bill Walton, In The Artist’s Studio

I’m really bummed to have missed The Gifting of Bill Walton’s Studio on December 4th, the extraordinary culmination of the ICA Philadelphia’s memorial recreation/exhibit of the late local master’s crowded workplace.

As ICA blogger/curator Rachel Pastan tells it, the event went of exactly as planned, with people trading memories and stories of Walton, and then choosing a memento from the studio–tools, brushes, scraps, materials, anything but finished sculptures–to take with them.

I guess it’s alright, because I’ve kind of been doing the same thing already, since 1996.

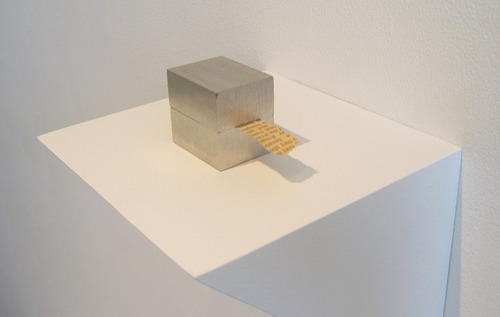

I found Bill Walton’s humble, powerful, minimalist, materialist sculptures when I was attending business school in Philadelphia. When Larry Becker Gallery had his second Walton show during my final semester, I splurged and bought a small piece–small even by Walton’s standards, though bigger than the gold or copper headless nail works he’d embed flush in the wall.

It’s a strip of lead an inch or so wide, carefully folded back and forth on itself into a little stack, almost like a cube. Pinched between one of the folds is a single 10″-inch blade of dried grass. In concept, it’s similar to the aluminum block & newspaper work Walton showed at Patricia Sweetow Gallery in 2005 [above]. [BTW, I love that he didn’t date his works. They exist among themselves, not in a timeline or progression.]

Becker explained that it was common to the streets of Philadelphia, and should I ever need to replace the grass, I could go out and find it. The species of grass is included on the label on the little custom-built archival cardboard case–it’s put away right now, so I can’t look it up–and Walton helpfully included a couple of spares behind a taped sheet of glassine.

Becker had shown the little sculpture on a small, white wall bracket about the size of a CD-case. For a while, I alarmed Becker by telling him how I had placed the sculpture on a cinnabar lacquered netsuke stand I’d found in the basement of my globetrotting landlady’s townhouse.

I was very interested at the time in the way Western modernism and minimalism resonated with Asian and Zen precursors–I was a groupie for John Cage’s Rolywholyover, which was at the Philadelphia Museum in 1995. And then later, when MoMA was choosing the architect for its expansion, I was translating criticism about Yoshio Taniguchi and his architect father Yoshiro Taniguchi, who had worked with Corbusier, designed the awesome mid-century modern Hotel Okura in Tokyo, and who founded Meiji-mura, an architecture preservation park which contains Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel.

But that’s several other stories. When my grass broke and my supply ran out, I began making a point to harvest a blade or two every time I went back to Philadelphia.

I kind of drifted away from a close following of Walton’s work after I left town, but Walton’s sculpture ends up occupying an outsize mental space for me, and it continues to link me to the city where Walton made it–and where I found it during my 2-year sojourn.

The transfiguration of Bill Walton’s studio [icaphila.org]

Untitled, By Michael David Murphy

This is so awesome. I know there’s no sound, but it seems like I can hear all those reality TV show team members’ hearts beating.

[Michael David Murphy via waxy]

On Politics, Damn Politics, And Art

I don’t know what, if anything, these mean, but these two stories last week made me wonder about the relationship of art and politics and Washington DC as viewed from a political/media perspective.

First up, and most disturbing, was the Washington Post Arts/Style section’s discussion of an American Psychology Association study [which, right?] linking creativity with lying & cheating. The Post was not alone in referencing artists–it took its headline, “Are artists cheaters?” from The Economist, “Are artists liars?”. But unlike the Economist, which actually didn’t discuss artists or art at all, the Post framed its entire story about the study around the inherent dishonesty of art and artists in a way I found facile and offhandedly hostile:

It’s not a wholly new idea. Being a liar is a requirement of being an artist, Ian Leslie argued in the Economist. “If art is a kind of lying, then lying is a form of art, albeit of a lower order — as Oscar Wilde and Mark Twain have observed,” writes Leslie. “Both liars and artists refuse to accept the tyranny of reality.”

Lying and cheating for one’s art — as in making up stories, cultivating a persona, and even appropriating other’s work — is different than cheating for personal gain, though. There have been prominent examples of artists who have engaged in both forms of it. Paul Gauguin’s numerous ethical breaches — beyond sleeping with teenage girls in his adopted homeland of Tahiti — included misrepresenting his paintings of the island to collectors back in France as a garden paradise, when in fact, it was colonized and stricken with alcoholism and disease.

So artists are prone, even required to “act unethically.” And so when someone who is, by every definition, an uncreative non-artist lies with the express, unethical intent to deceive, it is called art.

That’s according to an anonymous Mitt Romney campaign official rationalizing his candidate’s patently dishonest misrepresentation of a statement of President Obama:

“First of all, ads are propaganda by definition. We are in the persuasion business, the propaganda business…. Ads are agitprop…. Ads are about hyperbole, they are about editing. It’s ludicrous for them to say that an ad is taking something out of context…. All ads do that. They are manipulative pieces of persuasive art.” [The Reinvention of Political Morality, -NYT]

Which, of course, is all on the heels of Rachel Maddow’s ongoing mockery of Herman Cain’s delusional, lie-filled campaign as “performance art.”

This conflation of art and lying not only serves to justify, albeit cynically, the actual unethical behavior in the political realm, it also weakens and pre-emptively discredits art itself as a vehicle for protest, speech, idealism, or whatever intent/content the artist might have. It seems like one [more] way in which politics plays politics with art in ways that art is not even fully aware.

If there’s any good writing or thinking on this kind of thing, I’d love to hear about it. Honestly.

Gettysburg And The Disney/Ken Burns Effect

The new issue of Public Art Dialogue is out–as you know, right?–and it includes an article by Drake University art historian Maura Lyons that looks at how Disney, photography, and Ken Burns altered the Gettysburg National Military Park.

In the 1990s, the National Parks Service decided to reconfigure Gettysburg toward a “historically authentic” representation of the landscape as it appeared during the pivotal three-day battle in 1863, emphasizing the sites of action. After visiting the battlefield last year, I wrote [and wrote] about the problematic inconsistencies and selectivity of the strategy, which seemed to me like a retrofitted justification for an anti-modernist campaign to remove Richard Neutra’s Cyclorama building. Which it may still be, but not only that.

The NPS, Lyons argues, was trying to shore up the memorial’s relevance–and revenue–by responding to other presentations of Civil War history:

The landscape historian Brian Black has argued that the new direction for preservation at Gettysburg was partially motivated by the fact that, during the 1990s, the Walt Disney Company was planning to develop a historically themed park named Disney’s America in northern Virginia…NPS identified Disney as a possible economic threat an moved to solidify Gettysburg’s historical landscape as an authentic and authoritative one. In these efforts they could take advantage of a feature that Disney did not possess: the national park’s location on a notable battlefield.

Part of what helped kill Disney’s America, of course, was its proximity to another major Civil War site, the Memorial in Manassas to the Battles of Bull Run.

Alexander Gardner, The home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg 1863

As for photography, Lyons cites Gettysburg Then & Now, William Frassanito’s decades-long research project to identify and reshoot the sites of vintage, battle-era photographs. And a study by Jim Weeks, who found that

the desires of visitors, who want to see visions of the battlefield familiar to them from historical photographs, particularly from their deployment in Ken Burns’ documentary series The Civil War…helped prompt the restorations of the last 20 years… Weeks observes that “While in earlier phases Gettysburg controlled its image, by the latest phase images controlled Gettysburg.”

Lyons, Maura, “Memorialization and Marginalization: Vernacular Sites and the American Civil War,” PAD Journal, vol. 1, no. 2, pp163-191 [tandfonline.com]

Previously: Some pointers, or what to do with Neutra’s Gettysburg Cyclorama Center?

On Studying Why Americans Protest Art

Here is a PBS Newshour Q&A with Steven Tepper, discussing his research into why art–or the arts, really, since he looks at theater, libraries, music, too–triggers protests in some communities at some times and not others. He found that the protests are “always deeply rooted in local concerns.”:

STEVEN TEPPER: I looked at 805 cases of conflict across 71 mid- to large-sized cities in America. When all was said and done, and I looked at all the various things that might correlate with the cities that the highest rates of protest over a four year period in the 1990s, it was the rate of immigration in the decade prior that most strongly determined whether a city was a high city or a low city in terms of its protests levels. Cities that had experienced rapid population changes, in particular if the percent of foreign born had grown significantly, those cities were the most contentious in the late 1990s. And the argument in the book is that when people feel unsettled by the rate of social change, when the things around them are changing fast — economics, demographics, technology — art becomes something that they fight over as a way to reassert their values, reassert a sense of who their community is and where they fit into their community, who’s values still matter, what does a community look like going forward, and art becomes this amazing arena in which people negotiate their differences of opinions around the contours of their expressive lives together.

Great, so now we know? And we don’t have to read Tapper’s new book, Not Here, Not Now, Not That! Protest Over Art and Culture in America? Except that reading the book may be the only way to get a handle on the “social changes” Tapper mentions. Because they frequently seem to involve race, religion, and gay.

And I assume that he sets aside the culture-war-style protests started by organizations or politicians to gin up support or fundraising, which do not always have a local impetus. [Though even as I think about the Smithsonian’s “Hide/Seek” mess, the reality was, it was timed to disrupt the Congressional debate and coverage of the repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” so in a way, it was hyperlocal.]

tl;dw, reading the transcript is quicker: Conversation: Why Do Americans Protest Art? [pbs newshour]

Go ahead, buy: Not Here, Not Now, Not That! Protest Over Art and Culture in America [amazon]

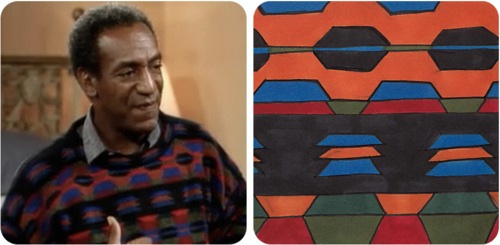

The Cosby Sweater Project

“Season 3, Episode 3: ‘Golden Anniversary'”

This is epic. Painting the key sweaters of The Cosby Show, one episode at a time, in chronological order. Which is awesome, not because it charts the evolution of the Cosby Sweater; any punk with a tumblr could do that. But because it’s fun to imagine Thomas Nozkowski’s reaction, as the seasons progress, and he hears the footsteps behind him, getting ever closer. And an occasional spastic, growly laugh.

The Cosby Sweater Project [thecosbysweaterproject.com via I wish I could remember]

On The BELLMAC-32, And Perhaps The World’s Largest Plotter Pen Drawing

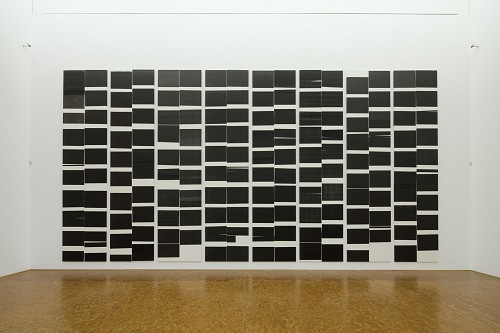

BELLMAC-32A Layout in the Ball Labs, Murray Hill Lobby, image: ieeeghn.org

Look closely, at least until I can track down a larger version of this snapshot.

Because it may be the world’s largest plotter pen drawing.

It’s a 20×20-foot layout of the BELLMAC-32, the world’s first 32-bit microprocessor, developed by AT&T just before they divested themselves of Bell Labs and the RBOCs beginning in the late 1970s.

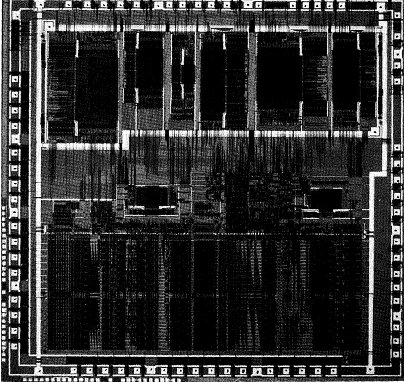

BELLMAC-32A microphotograph, via ieeeghn.org

According to a first-hand history of IEEE fellow Dr. Sung Mo (Steve) Kang, developing the BELLMAC-32 constantly uncovered the limitations of the design, testing, manufacture, and QA process for microprocessors:

Chip layout verification was another huge challenge. At that time, no CAD tools were available for the entire chip layout verification. As a result, we had to generate many CALCOMP plots and Scotch-taped them together to form a 20-foot-by-20 foot plot that was placed on the floor in a huge room. To make sure interconnects were formed properly, all terminals were labeled and wires were traced by using color pencils to make sure the lines ran continually. Although primitive, this method uncovered many errors and, in the end, produced error-free layouts and fabricated chips. We used a huge empty room in Building 3 of AT&T Bell Labs at Murray Hill or the main lobby area to complete the checking.

I love that creating the most advanced computer chip of the day still involved PhDs crawling across the floor with colored pencils.

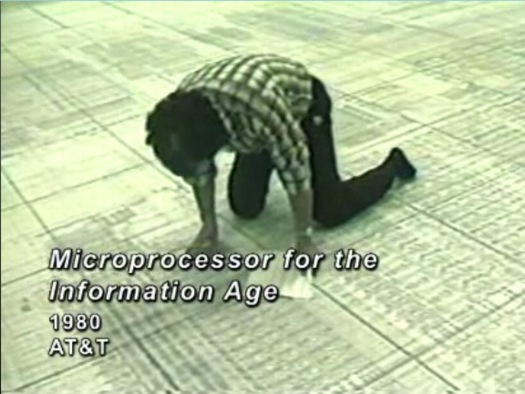

Still from Microprocessor for the Information Age, a 1982 industrial film on the making of the BELLMAC-32, via AT&T’s Archive

And of course, there’s the giant drawing itself, spit out by a printer in tiles and taped together. Was Wade Guyton even born when this all went down? Yes, but still. So awesome.

Now to track down a working CALCOMP plotter and recreate it. Because it’s probably too much to hope that AT&T or one of their computer engineer diaspora rolled all those sheets up and stuck them in their moisture-free basement. Right?

Microprocessor for the Information Age (1982) [techchannel.att.com thanks greg.org reader robin edgerton]

First-Hand: The AT&T BELLMAC-32 Microprocessor Development [ieeeghn.org]

previously: Shatner, plotter art, and the drawing machine as seen at the beginning of the digital age