Looks like I picked the wrong week to not start that awkward Twitstream juxtaposition tumblr.

Mormon Missionary And Companion, For Sale, By Jim Shaw

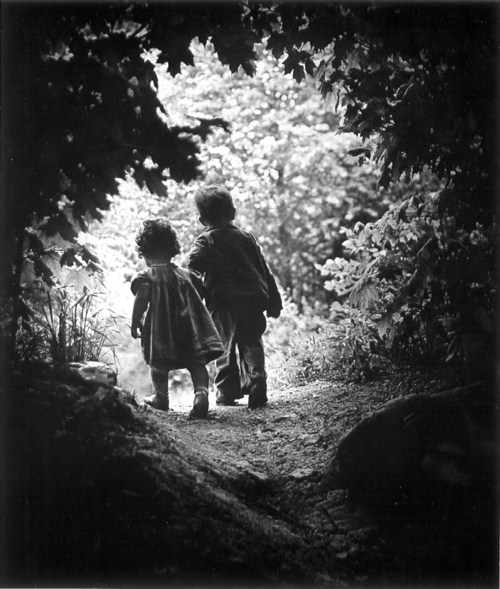

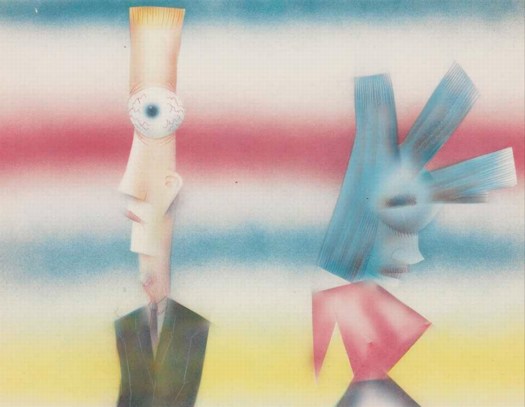

I don’t know how this slipped by me, but now it’s going up for sale tomorrow at Christie’s: a very early Jim Shaw pencil & airbrush drawing from 1981 with the obvious-now-that-you-mention-it title, Mormon Missionary and Prostitute Making Each Other Feel Guilty.

In 1981, Shaw wasn’t even really showing his art yet–the earliest group show in his current, abridged bio wasn’t until 1986. And he was years away from the unveiling of O-ism, his homebrewed, Life of Brian-style, parallel universe version of Mormonism, which he showed at the Swiss Institute and Metro Pictures in 2002. [O, and there was The Donner Party his awesome O-ist reimagining of Judy Chicago’s feminist masterpiece, The Dinner Party, which was at PS1 in 2007.]

Anyway, Shaw was still busy in 1981; Ed Ruscha helped him publish Life And Death, an artist book compilation of airbrush drawings that do look a bit like this Mormon Missionary here. Perhaps they are related.

Lot 30: Jim Shaw, Mormon Missionary and Prostitute Making Each Other Feel Guilty, est. $3000-5000 [christies.com]

From The Mixed Up Files Of Basically Everyone

What’s that, dear? Oh, nothing, just some legendary but unknown drafts for the first film adaptation of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, by veteran Hollywood screenwriter Benjamin Hecht.

After reading various references to the early 60s script, Jeremy Duns decided to go looking for it, and whaddyaknow, there it was, sitting in Hecht’s archive, which is at the Newberry Library in Chicago. Apparently, in the intervening decades, no one had ever bothered to actually look for it:

[T]hese drafts are a master-class in thriller-writing, from the man who arguably perfected the form with Notorious. Hecht made vice central to the plot, with Le Chiffre actively controlling a network of brothels and beautiful women who he is using to blackmail powerful people around the world. Just as the theme of Fleming’s Goldfinger is avarice and power, the theme of Hecht’s Casino Royale is sex and sin. It’s an idea that seems obvious in hindsight, and Hecht used it both to raise the stakes of Fleming’s plot and to deepen the story’s emotional resonance.

It’s exactly the kind of mind-boggling, serendipitous archive find that keeps me going on this Johns Flag hunt, even when the more skeptical part of me is saying, “Seriously, how could Jasper Johns’ first flag painting have been stolen, and missing, and then resurface in his own dealer’s office, and then disappear again, and no one knows where it is or even what actually happened to it?” But the more I dig and ask around, the more I find that, though plenty of people gossiped or speculated, almost no one has ever actually searched for it.

UPDATE/CLARIFICATION/APOLOGY/&C. Ha, ha, I guess if I think about it, yeah, my meant-to-be-exciting-thrill-of-discovery-in-uncharted-archives anecdote below could make actual archive professionals cringe. And I guess I didn’t think of that. OR mean it as any kind of criticism of the way the AAA works, just the opposite, in fact.

Fortunately, Barbara Aikens, the Chief of Collections Processing at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art took the time to correct some inaccuracies and clarify some of the wrong implications in my account. Which, I didn’t really– I mean, it was really meant to be kind of an amusing offhand story, not a transcript, which– Anyway. My bad.

A few trips ago, while researching at the Archives of American Art, I opened a white cardboard box, indistinguishable from all the others on the outside. But instead of the neatly labeled, acid-free folders, I faced a mishmash of giant envelopes, ragged edges, and old, manila folders. And a rubber banded brick of old AmEx bills. And some matchbooks. What a mess. It was more time capsule than archive.

In the middle of a sheaf of clippings and tear sheets, interviews and reviews and feature articles about Robert Rauschenberg, I came across an odd little card. No, it’s a transparency showing an Apollo alnding capsule. No, there’s three. Blue, magenta, cyan, waitaminnit, this is taped together by hand. It’s an object, maybe even a work, made of layered transparent sheets, similar to Rauschenberg’s editions made from multiple sheets of plexiglass. Shades (1964) is one; I have a similar set of plexi discs somewhere from 1970-1, in a boxed set of multiples titled, Artists and Photographs. Here you go: Revolver.

The other day, i recognized that space capsule image as the one in the Hirshhorn’s big Rauschenberg screen/painting, Whale, which is also from 1964. Maybe Bob sent that little objet home after a studio visit or something. But should it really be in here, in the archives, hanging out with greasy-fingered riff-raff like me? Maybe I should say something.

A couple of folders later, I carefully extract a large, tattered, manila envelope with something about a group show or benefit scribbled on the outside. The first thing I pull out is a signed Jim Dine drawing. Then another. The next one is an Oldenburg. I pull out a piece of black paper, which turns out to be a chalk drawing. A little dust gets on my hands. At which point–I mean, fingerprints, right? I’m totally busted–I call the attendant over with a hearty, “Uh, did you know there’s a bunch of original art in here?”

No, she did not, but yes, that happens, because, in fact, budget, priorities, low demand, &c., &c, some of this collection’s boxes had not been processed yet. I was probably the first person to even look through this box since it had come in over 25 years earlier. She gave me a stack of acid-free paper to slip in between the various drawings, and I decided that, though it looked like a blast, the stuff in the packet was obviously not related to my research–at the very least, if Johns’ Flag had been stuffed inside, I would’ve seen it–so I put it all carefully away.

I guess I’m just saying, there’s stuff out there. And no one’s been looking for it, so get cracking.

UPDATE I thought I was being helpful by not identifying the collection I was using here, but of course, Barbara knew right away what it was: the Alan Solomon Archives. The Solomon material had come into the AAA in waves, and the unprocessed box had actually entered the Archive in 2007, not, as I misunderstood, 25+years ago.

The presence of art, drawings, sketches, etc., while not a collecting goal of the Archive, is also not unheard of, and such material typically remains in accessible within the collection, where it is to be handled with care.

Barbara points out that while I made it sound like there I worked through a stack of acid-free paper, in fact, I only inserted three sheets between a couple of drawings. This is true. I was given a stack, but after replacing the works I’d taken out, I figured I’d leave the rest of the handling to the professionals, and so I closed up the box.

On the point of processing, I can’t do better than Barbara’s statement:

On average, we process and preserve about 500-700 linear feet per year; this includes writing full and detailed electronic finding aids that are available on our website. In addition, we are the only archival repository in this country that has a successful ongoing digitization initiative to digitize entire archival collections, rather than just selected highlights from collections. To date, we have digitized well over 100 collections, totaling nearly 1.000 linear feet and resulting in 1.5 million digital files. Archival repositories from across the country regularly consult with us on our large scale digitization methodologies, work flows, and infrastructure.

I would hate to think that users will think less of our major efforts here at AAA to increase access to our rich resources, or, worse, think that we do not care about the stewardship of collections. It is one of our ongoing mission goals and we devote considerable staff resources to our processing work. However, the work is never done to be sure.

And thank you for it. And for the clarifications. Carry on.

Casino Royale: discovering the lost script [telegraph.co.uk via daringfireball]

Gnome

Is there a tumblr for awkward Twitterstream juxtapositions? Because there oughta be.

Live From The Gramery Hotel

Warm nostalgia apparently equals d-bag public access video + time.

Reading Andrew’s report from the Dependent Art Fair, I kept flashing back to the Gramercy, and all the art in the bathrooms, and on the beds, and the insanely crowded hallways.

And whaddya know, there’s a link to a 1995 Gallery Beat episode from “the Gramery Hotel,” where those asshats wandered in on work by unknown artists like Mark Dion, and Tracy Emin, who was not quite protected by the utterly baffled Jay Jopling.

I’d totally forgotten how much I hated that show. And now I’ll probably end up watching the entire archive.

Classic Gallery Beat TV [gallerybeat.net via 16miles.com]

19th Century Photo Murals

Holy smokes. Of course you know that blogger/collector/scholar Jim Linderman published The Painted Backdrop: Behind the Sitter in American Tintype Photography 1860-1920. Which would make him the go-to guy for anyone with some actual, original, extraordinarily rare, painted 19th century photographer’s studio backdrops to sell.

Jim’s correspondent, in fact, has two. And they look awesome.

I love that they’re painted in black and white. Just like the 19th century itself.

Pair of original 19th century painted photography studio backdrops (for sale) [dull tool dim bulb]

Related: Frederic Remington’s black & white paintings-for-engraving

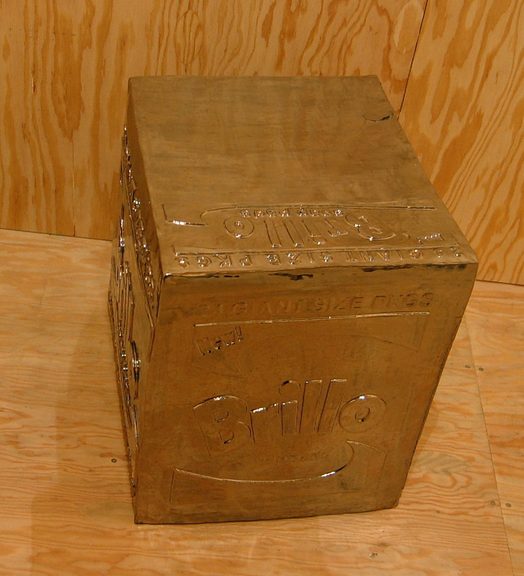

Stainless Steel Brillo

So awesome. Is there nothing that can’t be made better by Rirkrit chroming the hell out of it?

Fear Eats The Soul, Rirkrit Tiravanija, through April 16 at Gavin Brown’s Enterprise [gavinbrown.biz]

Awesome photo of chrome stainless steel Brillo Box and wok, one of many by Andrew Russeth [16miles.com]

Previously: Enzo Mari X Rirkrit Tiravanija

Extensive Brillo Box coverage on greg.org

Ab Eo Scientia A Quo Googleus

We went to Monticello this weekend–Jefferson was a complicated guy, brilliant, thanks for the Declaration etc, etc., but wow, high maintenance–and came away with a question about the Latin motto in the Jefferson coat of arms, which adorns the gate of the family cemetery where Jefferson and his white lineal descendants are buried.

Though we got the gist of it, the motto, “Ab eo libertas a quo spiritus,” had enough prepositions in it to make it hard to parse. But as we walked down the hill, trying to figure out “eo,” we realized we probably couldn’t. All we could do is look it up, and then we’d know.

That’s the binary situation the net has put us in: we either know something now, or we know it the instant after we look it up. There’s no figuring it out, no hints, just the answer.

Of course, this isn’t true for everything, or even most things–Google’s not just cold telling me where Jasper Johns’ Flag is, that’s for sure–but it’s true for enough things.

And that kind of bums me out a bit.

As for the motto, it does turn out to be a prepositional mess, which Jefferson may have added himself: “The spirit (comes) from he from whom Liberty comes,” or “Liberty comes from he who gives life.”

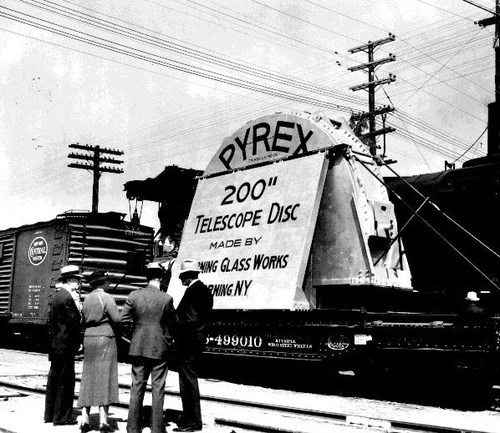

‘200 Inch Photograph’

Yeah, there’s photomurals, but anyone who’s spent some time poking around greg.org might have found my even longer-lasting photo obsession: the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey [see background and making of info here and here.] The idea is to take he 1,870 pairs of photos that resulted from this ambitious, 9-year project to systematically document the universe, into the art context. Where it had not, to my knowledge, ever been. [Thomas Ruff comes the closest, obviously.]

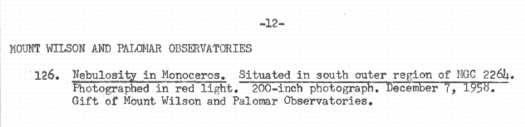

And so one would understand the excitement at finding this entry–right after Moholy Nagy and Wright Morris, and above Muybridge and Nadar–in the checklist [pdf] for the 1964 inaugural show in the Edward Steichen Photography Center, MoMA’s first dedicated photography galleries:

Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories

Nebulosity in Monoceros. Situated in south outer region of NGC 2264.

Photographed in red light. 200-inch photograph. December 7, 1958.

Gift of Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories.

Dude, not only was the Palomar Sky Survey IN an art context; it launched the art context. Dude, with a 200-inch photograph, it owned the art context.

So what did this look like? It must have been spectacular. But I can’t find any installation photos, or any reproduction of the work, or any writeups at all for what had to have been the biggest of the 239 photos on view in that first show, bigger, even, than Lennart Olson’s mural.

No problem, I can find the image from the artist’s [sic] side. Though it has been superseded by several far more advanced surveys, imagery from the 1950s-era POSS-1 is still available in the Space Telescope Science Institute’s Digitized Sky Survey. Here’s the red plate showing nebulosity in the constellation Monoceros on the south outer region of NGC 2264:

That’s the Cone Nebula down there at the bottom, just on the edge of the plate. Now imagine this photo printed nearly 17 feet tall, striking visitors to the newly reopened Modern with awe as they see how far photography has come.

And you’d have to imagine it, because it didn’t happen. There wasn’t a 17-foot tall photo gallery in the Museum in 1964. In fact, I’d wonder if the ceilings in the then-new Philip Johnson annex were even 16 feet.

Also, it turns out that the POSS-1 image of NGC 2264 was made on Nov. 30, 1951, not Dec. 7, 1958. So the 200-inch photograph does not refer to the print size. It is likely a reference to the telescope that took it, Palomar’s Hale Telescope, which was the largest in the world from 1948 to 1993. It was conceived by George Ellery Hale, who secured $6 million for the project in 1928 from the Rockefeller Foundation.

Corning cast the 200-inch mirror from Pyrex in 1934-36, and it was transported across the country by train to Pasadena where, after eleven years of polishing and shaping, the 40-ton mirror was hauled to the top of Mount Palomar and installed in the 1000-ton, Pantheon-sized rotating observatory. Edwin Hubble took the first photograph with the 200-inch telescope in January 1949.

I still haven’t found the details of the photo MoMA exhibited, but the mirror story makes up for it a little. And I thought artists were crazy.

Oh, That’s Right, Philip Johnson Was A Nazi

So I’m searching through the New York Times archive, trying different combinations of keywords to find references to photomurals at the Museum of Modern Art, and I find this intriguing 1934 headline:

TWO FORSAKE ART TO FOUND A PARTY; Museum Modernists Prepare to Go to Louisiana at Once to Study Huey Long’s Ways. GRAY SHIRT THEIR SYMBOL Young Harvard Graduates Think Politics Needs More ‘Emotion’ and Less ‘Intellectualism.’

But the Times’ archives purchasing has been acting up for a few months [it’s not just me, right?], and my 10-pack of articles has been stuck at five since October, so I can’t click through to see who these Museum Modernists are.

And a couple of weeks ago, I could have searched the rest of the internet and not found the answer, but now that Google has added the complete run of Spy Magazine, a search for “Museum Modernists” and “Huey Long” turns up one result: the devastating 1988 Spy article by Michael Sorkin detailing the fascist and Nazi activities of the young Philip Johnson.

I mean, holy crap. Gray Shirt Their Symbol barely scratches the surface. Johnson’s fellow modernist was Alan Blackburn, the Museum’s executive director. As MoMA’s archive puts it, “Both Blackburn and Philip Johnson resigned from the Museum in December of 1934 to pursue outside interests.”

Those interests ranged from donating large sums of money to and founding a youth wing for raging anti-semitic demagogues such as William Lemke and Father Coughlin to spying for the Nazis during the invasion of Poland.

Where was Philip? Spy, Oct. 1988 [google books]

Here’s an image of the Times article and photo. Amazingly vague. [uncommonplace book]

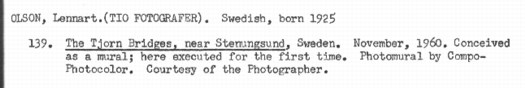

Lennart Olson, Photomuralist

In other seemingly obscure art historical news from 53rd Street: while Googling around on Compo Photocolor, I found this mention in a 1964 press release [pdf] from The Modern, which turns out to be a checklist for the newly remodeled and reopened museum’s first dedicated photography galleries, The Edward Steichen Photography Center:

OLSON, Lennart. (TIO FOTOGRAFER). Swedish, born 1925

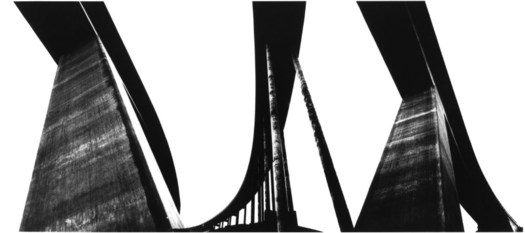

139. The Tjorn Bridges, near Sternungsund, Sweden. November, 1960. Conceived as a mural; here executed for the first time. Photomural by Compo- Photocolor. Courtesy of the Photographer.

So just like the first exhibition in MoMA’s original 53rd Street building 32 years earlier, the first show in the new building includes photos specifically conceived as a photomural.

[via]

Olson was a well-known Swedish photographer, though from this 2010 bio for him, his MoMA exposure was the source for much of his hometown fame. And unfortunately, the namechecking is hardly mutual. The only mentions of Lennart Olson on MoMA’s website are from the period press releases.

Steichen included Olson’s work in a 1953 survey of Postwar European photography [pdf]; in 1960, Steichen ends the department’s announcement of new acquisitions [pdf] with this: “Of particular interest is an 8-foot wide photographic panel, “Project for a Mural,” (1960) by Lennart Olson.” Which sounds related to the work that debuted in 1964.

In 1960, Olson was also included in an exhibition titled, “The Sense of Abstraction,” [press release pdf], which was organized by Grace Mayer and Kathleen Haven, who had put out a call for hundreds of photography portfolios. [It’s interesting to read that as a corollary to “straight” photography, abstraction meant producing “works whose sole function is to delight–or affront–the eye.”]

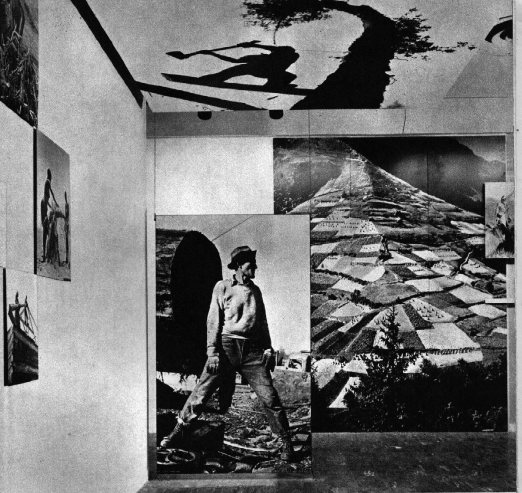

Anyway, Olson’s “monumental architectural studies” opened the show; the Museum described them as “abstract through individualistic interpretation of design.”

[via]

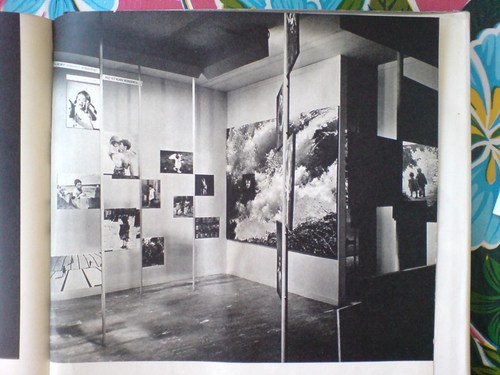

I can’t find images of the 1960 study, but here is an installation shot of the 1964 mural itself. At first and second glance, the scale and form remind me of Franz Kline, who arrived at his signature large-format abstractions by enlarging small drawings projected onto the wall.

Chief, 1950, acquired by MoMA in 1952

The prominence MoMA gave to Olson’s large, abstract photomural seems to have been confined to the end of the Steichen era, aka the early 1960s. I don’t have any way yet to figure out whether this resonance between Ab Ex painting and large-format photography was conscious or coincidental, but it sure seems convenient.

Talking with artist John Powers today about this speculative painting vs photography dialogue/contest, he suggested looking, not at the artists themselves, but at their mediators: the curators and the museum. It’s easy to imagine curators sharing an attraction to the powerful scale and immersive gallery experience of large, trophy-sized artworks, just as it’s easy to imagine the ambitious size appealing to painters and photographers alike.

On the dust jacket for the book version, Steichen rather immodestly calls The Family of Man “the most ambitious and challenging project photography has ever attempted,” which serves as “a mirror of the universal elements and emotions of the everydayness of life.” Doesn’t sound like he regretted giving up painting much.

‘Coaxing the Illusion of Crisp, Clear Light from Pigment’

When I first came across the pixelated Dutch landscapes on Google Maps , I imagined the polygonal camo distortions hovering over the sensitive sites. From the ground, I thought, maybe it looked like a Gerhard Richter overpainted snapshot.

But now I think it looks more like the bright, beautiful gouaches by Louise Belcourt which Sharon featured on Two Coats of Paint recently.

Images: Louise Belcourt’s place in the world [twocoatsofpaint.com]

‘Do-It-Yourself Existential Individualism’

Frieze’s 20-year retrospective of itself continues apace, and wow, it’s like running into an old flame on a train platform.

I hadn’t thought about Daniel Birnbaum’s 1996 essay, “IKEA at the End of Metaphysics” in years, but wow, it’s just all flooding back.

From a Heideggerian perspective IKEA best sellers such as ‘Billy’, ‘Ivan’, and ‘System 210’ do not represent a corruption of everyday life, but have merely formalised what is already there; the IKEA catalogue only makes the tendency towards uniformity more conspicuous. Heidegger’s global ‘levelling’ is not a critique of the common forms of everyday life as such, but of their passive acceptance. At the end of metaphysics, levelling is complete – no one questions the catalogue.

Obviously–well, now it’s obvious, anyway–my own Ikea X Enzo Mari mashup project has its origins in the critical perspective of the company and its ideology which Birnbaum mapped out 15 years ago, and which I absorbed.

Also, I’m reminded how I miss Jason Rhoades.

IKEA at the End of Metaphysics [frieze.com/20/ via ronald jones]

Where To Make A Steichen-Style Photomural: Compo Photocolor

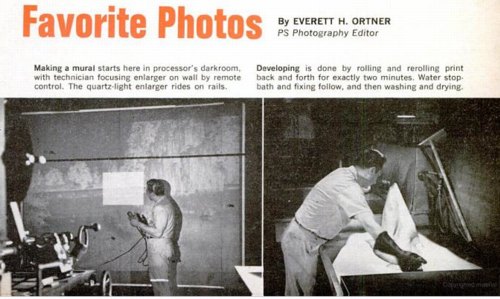

While trying to find out where and how to make a photomural, or at least how they used to make them, I found this slightly ridiculous 1966 Popular Science article about making photomurals in your very own home. And how you basically shouldn’t do it, but instead just mark up a negative and send it off to a photo enlarger somewhere.

Someplace like–hey-o!–the outfit mentioned in a caption, “Compo Photo Color, 220 W. 42nd St., NYC, specialists in murals and exhibition prints who did famous ‘Family of Man’ photo show.” And so it comes pretty much full circle, back to the most famous photomural exhibition of all.

So who is Compo Photo Color? Or was. Immediately available references are pretty scarce, but Compo seems to have been in business from the 1950s until the early-to-mid 1970s. Its principals were a German immigrant photographer Richard J. Schuler and Ernest Pile, and it was eventually consolidated into Wometco Photo Services, a division of the Miami-based movie theater owner. But back to the apparent heyday, in the 50s.

In a 2001 interview, photographer Wayne Miller, who was Steichen’s assistant and co-curator on Family of Man, and who contributed the most images to the show, talked about working with Compo on the prints:

Riess: About Gene Smith, can I ask you to repeat the story that I lost last time about asking Gene Smith for a print of that image in The Family of Man?

Miller: Oh yes. In The Family of Man, after we had made our final selections of what pictures we wanted to have in the exhibition we asked some local photographers if they’d like to make the print for us, or would they give us the negative and we ll have the print made by Compo Photocolor in New York. Actually we wanted Compo Photocolor to make all of them so the prints would have a commonality, and they would match the other prints quality-wise. And they were very good technicians.

But in this case, because of Gene, he wanted to make the prints, he didn t feel anybody could make the print as well as he could. And he invariably spent not only hours, but days in the darkroom. In fact, in a Life story he would disappear in the darkroom and return, and you almost– here he was seemingly weeks or months afterwards, with a beard and other things, and with the final prints. And it would drive the Life people mad.

In this case, we had a print that I’d found in the Life morgue of what he [Smith] called “A Walk in Paradise Garden,” something like that, of two children walking out from underneath this frame of bushes. A nice picture, and we wanted to use it at the end of the exhibition. It was going to be about, maybe 30″ x 40″.

I told Gene we wanted to do this and asked him if he’d like to make the print, and yes, he

certainly wanted to make the print. So I arranged for him to get the necessary paper and

chemicals to do this, because his wife Carmen said, “Don t give Gene the money for it, because he’ll spend it on other things.” So after he told me what he wanted, I did get the materials for him. And I gave him a deadline, knowing that he was often not able to meet a deadline, of about three weeks early. So he took this material.

Now the print we had that I’d gotten out of the files had been handled a great deal and it had some cracks in it. It was dog-eared, and it wasn’t a fine print at this point. So at the same time I gave these materials to Gene I sent the print from the Life files over to Compo Photocolor and asked them to make a copy of it, make a negative, and make a print to size. Just so we wouldn t get stuck in case he didn’t come up with the print. Later, when he did do it, we could always replace it. And sure enough, the deadline came and went and we had to put this copy print up on the wall. Because Gene hadn t shown up with his.

A couple of weeks later Gene shows up with these photographs rolled up under his arm. We went up to the museum exhibition space in the morning because the museum didn t open to the public until noon. And I took this print that we had down off the wall, and he unrolled his prints. He had half a dozen of them there, different qualities, and he laid them out beside this print. I was worried about this because I know how he struggles and works so hard on it. He will darken this or lighten that, and he ll use ferro cyanide to bleach little bits. And the delicacies with which he treats a print are just great, they re very great. So I was interested in seeing how it would work.

He laid his out, and he stood back there and looked at these prints. And he walked around a little bit and looked at them some more. Finally, he said, “You know, I think the print you have on the wall is the best one. Let s use that one.” [laughter] So he rolled his up and went along.

That I think points out the fact, I believe, that when you make a photograph, a print of a

photograph of larger than normal size, it picks up a new quality other than one of maybe an 11″x14″ or something. But one like this, maybe 30″x40″, it has a new quality to it.

You know, it didn’t occur to me at all until just now, but Paul Rudolph designed the installation for Steichen’s Family of Man, which was photographed by Ezra Stoller, in January 1955,

the same year Robert Rauschenberg was collaging photos into such giant combines as Rebus. Hmm.

On War-Era Murals

The question or theme or whatever hadn’t crystallized for me, but when Tyler linked to the previous two posts about Lt. Comm. Edward Steichen’s wartime propaganda exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, he noted that “there’s a lot of art historical work yet to be done on the impact World War II had on art and artists.”

It’s an interesting way to consider my fascination with the aesthetics and paradoxes of photomurals: their apparent historic status as something other than artwork, much like the photographic medium they’re derive from; their powerful scale, which creates a certain kind of all-encompassing viewing experience that is typically associated only with the later works of revolutionary “high art,” namely the Abstract Expressionists; and of course, the abstract and modernist aspects of the images themselves.

I’m not ready to go beyond the grand theory of “this looks like that,” but I keep seeing and finding resonances between photomurals, which were born in the Depression and came of age during WWII, and some of the major developments of postwar art.

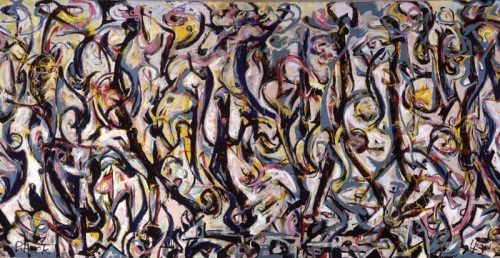

Mural, Jackson Pollock, 1943, collection: UIMA

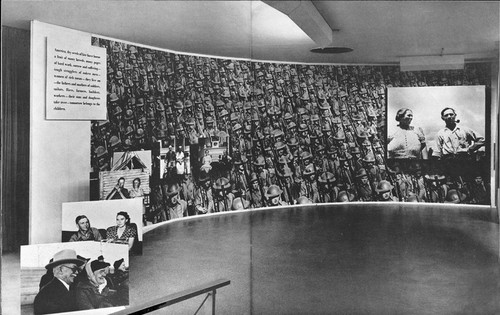

I mean, I’m re-reading Tyler’s interview with Pepe Karmel about Jackson Pollock’s Mural [above], which was painted in 1943, and there are moments where I can’t help thinking about the 15- and 40-foot images in Steichen’s 1942 Road To Victory show:

It’s an important painting for Jackson Pollock because it’s the moment that announces his future as a painter of large, mural-scale paintings that become environments, and furthermore paintings that are in this distinct, all-over style that changes people’s idea of what a painting might be.

…

It’s like Barnett Newman’s Vir Heroicus Sublimis or Pollock’s own Number 1, 1950. You have to be there. You have to be standing in front of it and feel it filling up your field of vision and feel it wrapping around you and feel yourself falling into the field of the painting. If you don’t have that experience first-hand, you won’t get the feeling of the painting.

…

MAN: You talked about how important the painting was in terms of Pollock’s oeuvre. Can you detail why it’s so important to what came next in American and modern and contemporary art?

PK: The next step is off the wall and out into space. In contemporary art that deals with installation as an art form, which comes out of those paintings in 1950 and that comes out of this painting in 1943. It just doesn’t get more historic than this.

It’s truly a kind of unrecognized monument of American art.

Which isn’t to say that Pollock was referencing or even influenced by photomurals, just that both Herbert Bayer’s installation of Steichen’s photos and Pollock’s first epic-scale painting create an overwhelming spatial experience.

Photomurals were out-and-proud propaganda which had connections to filmmaking and the cinematic screen and to world’s fairs, [See Alvar Aalto’s Finnish Pavilion at the 1939 World’s Fair and the Japanese pavilion at the Golden Gate Expo that same year].

Which is one of just a handful of references to photomurals in LIFE magazine’s archives. In a moment of greg.org confluence, LIFE’s most prominent depictions of photomurals are not in museums or world’s fairs, but in political rallies–they are the ur-Sforzian backgrounds. For example, In 1949, FDR Jr. has a giant wall of smiling children behind him at a UAW convention. A chorus line of garment workers kick in front of a selection of “union heroes.” And when he spoke in Boston in 1949, Winston Churchill stood in front of an aerial photomural of the MIT campus [above] which reportedly “confused [the] television audience.”