Alright, the search is on; I’m working to trace the history of Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine Short Circuit and especially to figure out what happened to Jasper Johns’ flag painting, and when and how Sturtevant’s flag painting got in there, and what all that means.

When I first wrote about Short Circuit last week, there was no date or story or anything about how the flag disappeared, only that it had been described as “stolen.”

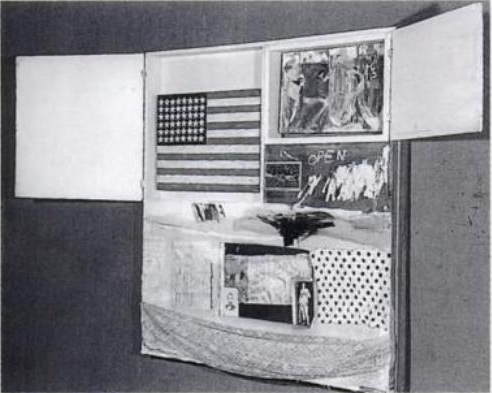

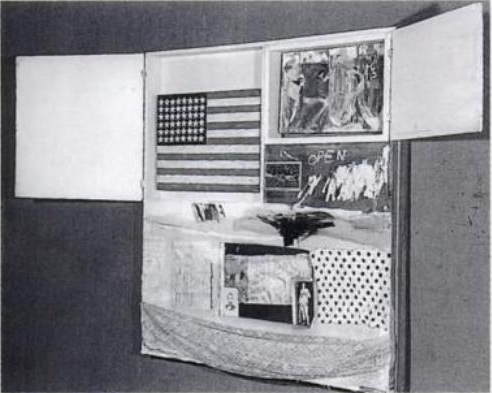

In his 1997 Rauschenberg catalogue, Paul Schimmel had mentioned the Johns Flag–which, like a painting by Rauschenberg’s ex-wife Susan Weil, was incorporated into the combine behind two cupboard-style doors–had been stolen while the work was on exhibit. Now I’ve found out where and when that was, I think.

In 1976, Walter Hopps curated a Rauschenberg retrospective at the National Collection of Fine Arts, which is now the Smithsonian’s Museum of American Art. From the catalogue:

The original flag painted by Jasper Johns was subsequently stolen and was replaced by a replica painted by Elaine Sturdevant [sic] at the time of the exhibition “Art in Process: The Visual Development of a Collage,” held at the Finch College Museum of Art in March 1967. In his statement for the exhibition catalogue, Rauschenberg commented, “This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.”

For Rauschenberg the work remains “a double document” of the past and the ongoing present. Recently, in commenting on the stolen encaustic, he has stated, “Some day I will paint the flag myself to try to rid the piece of the bad memories surrounding the theft. Even though Elaine Sturdevant did a beautiful job, I need the therapy.”

Much to unpack there, especially in that second quote. Wow.

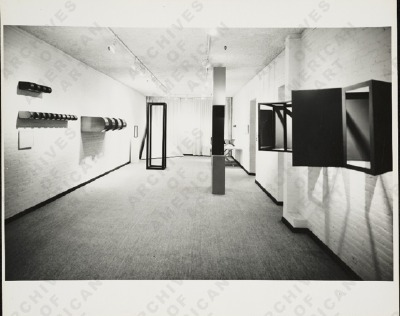

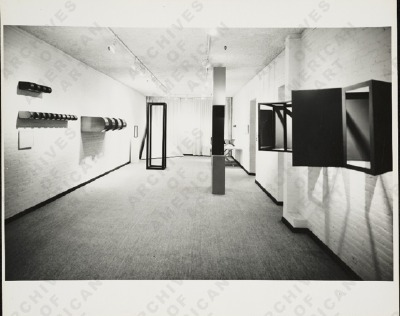

But at least now we have a date and a place: Finch College Museum, March 1967. Finch was a women’s college on the Upper East Side. From the archival photos, the Museum looks like the basement floor in one of the school’s townhouses on East 78th Street [between Madison and Park]. In the 60’s, under the direction of Elayne Varian, the Finch Museum had a pretty advanced contemporary exhibition program.

[One of the top Google hits for Finch College turns out to be from Calvin Tomkins’ Rauschenberg bio. Legendary dealer Ivan Karp tells the story of how he was showing some girls from Finch around Castelli Gallery when Roy Lichtenstein walked in with his first comic panel paintings under his arm.]

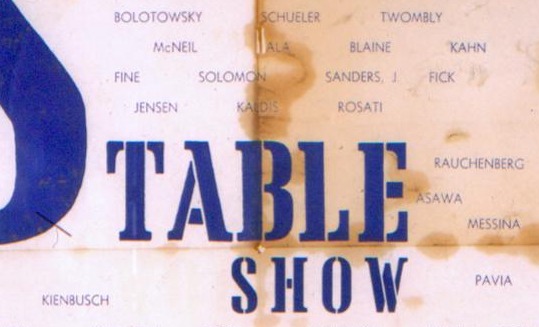

“Art in Process” was an innovative series of exhibitions that placed sketches and models alongside finished works to examine the working practices of contemporary artists. An “Art in Process” show on Structure, for example, which went up in 1966 within months of the Jewish Museum’s seminal “Primary Structures” show, contained works by Lewitt, Judd, and Smithson, including the latter’s Enantiomorphic Chambers [on the right in the image above, via aaa.si.edu], which, ironically, was also lost.

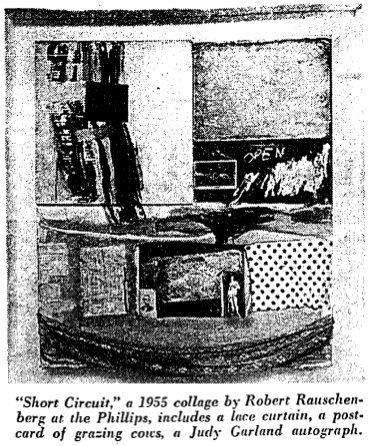

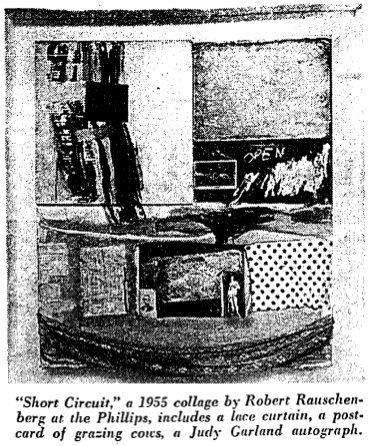

Anyway, after its Spring 1967 debut at Finch, the Collage show traveled under the auspices of the American Federation of Arts. Though I can’t find the complete list of venues, in February 1968, it came to the Phillips in Washington, DC, where the Post’s sportswriter-turned-art-critic Paul Richard panned it by repeatedly dismissing collage as mindless random gluing and comparing it to the tacky “Snoopy’s valentines” everyone had just exchanged.

Except for Short Circuit, that is, which Richard called, “the best in the show.” Take note of his description, though, and that he specifically mentions reviewing all the extra documentation of the show in the Phillips back offices:

(When first exhibited, viewers could open the collage’s two hinged doors to discover two paintings, one a flag picture by Jasper Johns. They’re no longer visible. The doors have been nailed shut.)

No mention of the theft, the missing Johns, or any replacement. And the doors are shut on the paintings by the artist’s ex-wife and ex-partner. No musing, please!

Despite the mind-boggling variety of its components, the piece somehow holds together. The composition is bright and strong. It’s nice to think about (the viewer can muse on the various associations generated by relics of Miss [Judy] Garland, Lincoln and [John] Cage), but tracing the development of this work would be a hopeless task.

We shall see, Mr. Richard, we shall see.