Via Ubu comes a provocative essay, “Constructed Anarchy,” from the poet and John Cage critic Marjorie Perloff. She takes the death of Merce Cunningham and the company’s plans to dissolve after a worldwide farewell tour as an opportunity to ask a tough question of Cunningham’s and Cage’s philosophy: basically, if art is life, what happens to it after you’re dead?

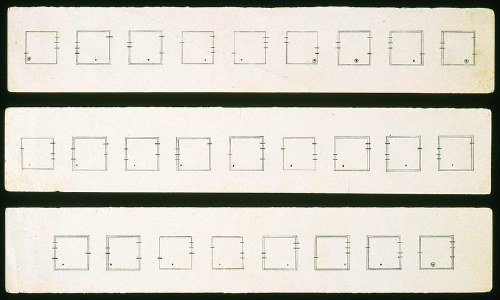

When in June 2010 I had the chance to see Roaratorio performed at the Disney Concert Hall–a beautiful Roaratorio but no longer graced by the presence on stage of Merce or by the actual speaking voice of John Cage–what seemed especially remarkable was the tight formal structure of a composition once billed (both in its radio and dance incarnations) as an anarchic Irish Circus, bursting with random sounds and unforeseen events. For, however differential the leg, arm, and torso movements of the individual dancers (sometimes in pairs or threes, sometimes alone), all are metonymically related in a network of family resemblances, and all are, as the charts show, mathematically organized. Yet wasn’t it Cage who defined his music as “purposeless play”–“not an attempt to bring order out of chaos . . . but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord”? And wasn’t it Cunningham who insisted that dance “is not meant to represent something else, whether psychological, literary, or aesthetic. It relates much more to everyday experience, daily life, watching people as they move in the streets”?

The very life we’re living: the Gelassenheit so seemingly central to Cage-Cunningham was hardly anarchic, much less unpredictable. But their own statements, and hence the critical writings about their work, have regularly insisted on what Joan Retallack, in her seminal series of conversations with Cage, calls “an aesthetic pragmatics of everyday life.” “[Cage] told me,” she recalls in her Introduction, that “the art that he valued was not separated from the rest of life. . . . The so-called gap between art and life didn’t have to exist” (Musicage xix-xx). And Cunningham repeatedly made the same point, using traditional ballet as contrast.

Or that’s how it used to be.

It sounds convincing: to see RainForest or Roadrunners, Channels/ Inserts or Beach Birds, is to perceive that there is no central focus or storyline, no prima ballerina flanked by a corps de ballet, no symmetry or detectable unifying principle. But if the dancers are free to introduce their own variations and tempo, if the piece is as non-hierarchical and collaborative as Merce suggests, why has each work (dance and music) been plotted out geometrically and arithmetically? Why have the dancers received so much less acclaim than Cunningham himself, in his role as director /producer /choreographer? And why has the decision been made that the ensemble will not be able to function without him? Similar questions can be put about Cage’s work: is his recorded voice reading Roaratorio essential to the work? Can a “decentered” Cage Musicircus perform without Cage?

The more we probe such Cunningham-Cage concepts as “free form” or “anarchy,” the more apparent it becomes that theirs is an anarchy that is carefully simulated. Their works are by no means “happenings,” in Allan Kaprow’s sense of the word, nor is Cunningham producing performance art.

As in Duchamp’s case, no “accident” is really accidental, and discipline is central. [emphasis added because, yow, kinda harsh]

Perloff’s argument is definitely worth a read, and she had a front row seat–and she quotes longtime Merce collaborator Carolyn Brown and others–on Merce and Cage’s egos and steely artistic wills, which seem to undermine a carefully cultivated [or at least prevailing] laissez-faire, see-what-happens image.

But I’m just half-informed enough to take issue with Perloff’s takedown. She sets up seeming contradictions between professions of randomness and artistic control, but I think that’s false and unfair. Cage wasn’t an evangelist for randomness, nor for anarchy, but for chance and chance operations. And there’s a meaningful difference that I suspect Perloff knows well.

Randomness is whatever happens, but chance operations is a tool for determining what happens. Perhaps Cage and Cunningham’s meant their obliteration of the distinction between art and life, between music and sound, between dance and movement, to be a production strategy for the artist, not a life strategy the audience.

Constructed Anarchy [lanaturnerjournal.com via ubu]

Interesting/related, and the 2nd time in 2 days to see Cage compared to Warhol: Ubu founder Kenneth Goldsmith’s 1992 review of Perloff’s first posthumous Cage essay. [electronic poetry center]