Seriously. It’s been eating at me for over a year.

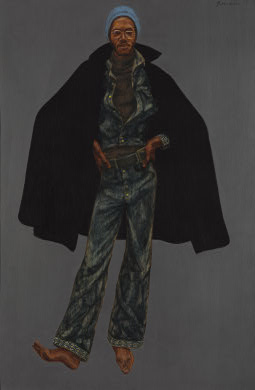

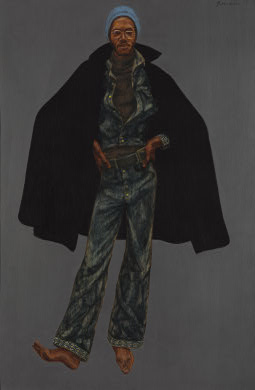

Like everyone else who saw them in “Birth of the Cool,” Nasher Museum curator Trevor Schoonmaker’s retrospective, I was in awe of Barkely L. Hendricks’ straight-up full length portraits from the early 1970s, which were usually of folks who didn’t have many full length portraits painted of them.

Hendricks is a resolutely representational painter, which is not to say traditional; his figures float on empty white [or gold leaf] canvas. My favorites, like Sir Charles, aka Willie Harris, above, have a triptych/multiple exposure/montage composition. They’re not just portraits, they’re paintings, in a defiant, powerful sense.

In fact, Sir Charles, painted in 1972, won my first, second, and third vote in the winter of 2009 for paintings the Obamas should hang in the White House. You remember the criteria: the work had to be in a national museum, but borrowing it couldn’t remove it from public view.

Perfect, Sir Charles is owned by the National Gallery of Art, and the collection database showed it wasn’t on view [of course not, because it was traveling as a star of Hendricks’ show.]

And here’s where the double mystery kicked in: Sir Charles has NEVER been exhibited at the NGA. Neither has the other incredible Hendricks painting in the collection, George Jules Taylor, also 1972.

How could this be? The National Gallery is cutting edge enough to acquire major works by The New Painting Hotness [sic] before he’s on the cover of Artforum, they make the rounds in one of the most admired museum shows of the year, and yet they never show them themselves? EVER?

[UPDATE: Uh, no. An unidentified reader has correct me, thankfully. The NGA’s location records for the Hendricks works do indeed show that they have been exhibited at various times in the Gallery. The online exhibition history apparently refers only to curated shows, in or out of the Gallery. For more details on this correction, check this post.]

The kicker, of course, was right there in the collection info page. The accession numbers for the two Hendricks paintings are 1973.19.1 and 1973.19.2, which means, obviously, that they were acquired new. In 1973, the National Gallery purchased a newly minted Yale MFA’s triple portrait of the corner drug dealer outside his New Haven studio. It completely blew my mind.

There had to be a story there, I figured, so I started digging. And came up nearly empty at every turn. I thought I’d just look in the NGA’s archive, but there was nothing there. Who was the curator savvy enough to find his or her way to Hendricks back then? No idea, it turns out the NGA did not even have a curator dedicated to modern and contemporary art until the 1980s.

The NGA website has basically everything that the institution knows about the paintings. Since I started asking around the NGA several months ago, the provenance info has been updated to say when they were acquired: May 1973. They came from the Kenmore Gallery in Philadelphia, where Hendricks had his first solo shows. They’re the only works in the collection with the credit line, “William C. Whitney Foundation.” Not a lot to work with.

But not nothing. William C. Whitney’s son Harry Payne Whitney’s wife Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney founded the Whitney Museum, where Hendricks had been included in a major–and controversial–show in 1971, “Contemporary Black Artists in America.” The show had grown out of a compromise with the black art community, which, along with important groups like the Art Workers Coalition, had criticized the persistent absence of non-white artists in the museum’s collection and program. When the black advisers to the show’s white curator quit, a large group of artists withdrew and called for a boycott. A high profile museum show might explain how Hendricks got on the art world’s radar, but not how his work made it into the NGA.

Whitney Whitney Whitney. It turns out the William C. Whitney Foundation had been created, not by the Museum Whitneys, but by Harry’s sister, Dorothy Payne Whitney in honor of their father, but for the use of her son, Michael Whitney Straight. At least according to Tragedy and Hope, by Carroll Quigley.

Get out your foil hats and turn up Glenn Beck, because Quigley is the highly influential Georgetown history professor whose controversial writings on the history of Anglophile secret societies is the tenuous basis of classic rightwing conspiracy theory. Beginning in 1970, Quigley’s work was mutated, Pale Fire-style, by Beck’s favorite Mormon wingnut academic W. Cleon Skousen, into a Grand Unified Conspiracy Theory between the Communists, JP Morgan, and everyone in between.

And guess who Mike Straight’s dad worked for? JP Morgan. And guess who Mike Straight was a spy for while he was at Cambridge in the 1930s, and later after he moved back to the US to work at the State Department? The Soviet Union.

His Communist sympathies didn’t last through the war, and when Straight was being considered for the head of the new National Endowment for the Arts the Kennedy Administration was planning, Straight came clean, exposing the rest of the Cambridge Five spy ring. Straight became the deputy head of the NEA, which didn’t require a Senate confirmation. And he wrote extensively, both about his own spy history, and about the formative people and stories of the NEA.

None of which sheds any light at all on the NGA and their Hendrickses.

Finally, after exhausting every potential archival source, I contacted Trevor Schoonmaker at Duke’s Nasher Museum. Who, it turned out, was just taking paternity leave, perhaps I’d rather talk to Barkley himself?

So a couple of weeks ago we set it up to chat on the phone. Here’s how it went down:

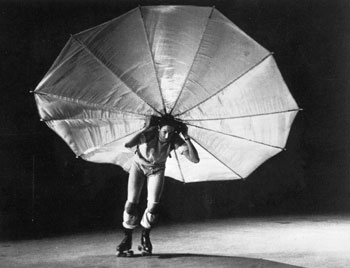

J. Carter Brown himself had gone to the Kenmore Gallery and asked Hendricks’ dealer Harry Kulkowitz to see some paintings for possible acquisition. The selections were made, and Kulkowitz and Hendricks brought the works to DC for consideration. “I went down with Harry, and it was a situation where the pieces were pretty large, and I had to design the stretcher to fold. So once we got down, i unfolded them and put them together. and that set the acquisition ball in motion.”

Brown apparently tapped Straight personally for the acquisition funds. I didn’t think to ask how much the Gallery paid, but Hendricks said in an interview last year that, “I had reached the $5,000 ceiling that black artists have, in 67 or 68. Someone said that once (that there is a $5,000 ceiling for black artists).” And when I asked Hendricks about the importance of being in the Whitney show, he laughed it off, saying that “Black people were fashionable at that time.”

Well, they’re kind of hot right now, too. “Birth of the Cool” wraps up at the Contemporary Arts Museum in Houston on April 18th. What better time for the National Gallery to finally celebrate its illustrious former director’s prescient acquisitions by finally showing a Hendricks painting or two [again, see correction above] in Washington DC?