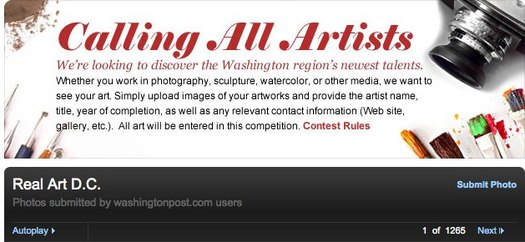

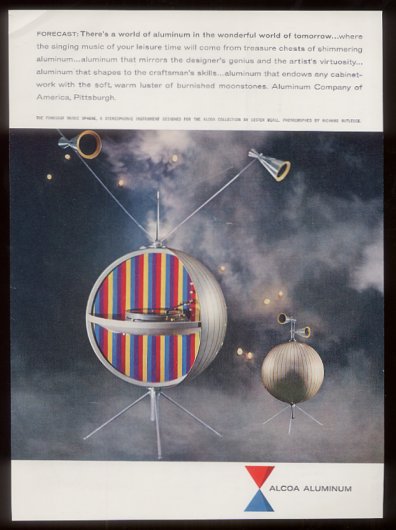

Following on to their 2008 retrospective of ZERO, Sperone Westwater is exhibiting work by the group’s co-founder, Otto Piene. ” Otto Piene: Light Ballet and Fire Paintings, 1957-1967″ runs through May 22nd. [16 Miles has very nice installation shots.]

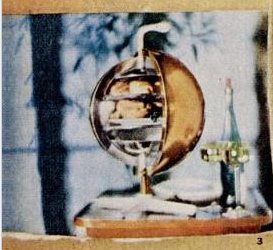

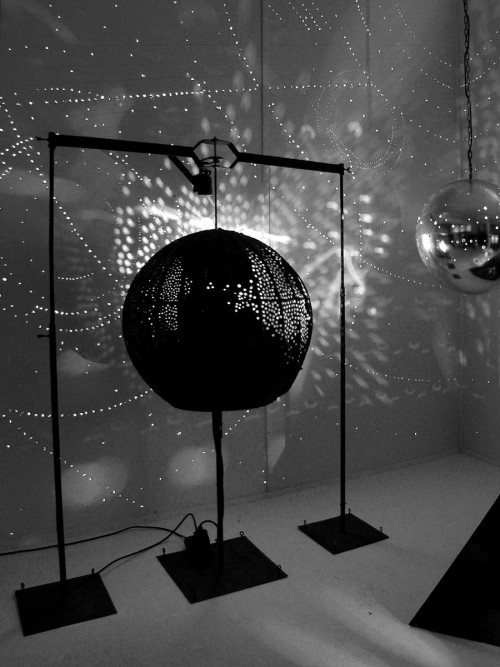

While I am stoked to see Lichtballet, 1961, above, the piece I’d most like to see, the silver sphere hanging on the right, is not in this show. This photo, by Günter Thorn, turns out to be of Lichtraum [obviously] from “Bilder, Objekte, Grafiken und Lichtraum,” an exhibition last winter at the Kunstverein Langenfeld.

Last year, the Pompidou had a cheeky, brilliant exhibition, Voids: A Retrospective, which consisted of nine empty galleries, each a different re-creation of an artist’s showing of a void. [John Perrault discussed the show at length in March 2009.] I feel I am now tiptoeing backwards into a similar project, a retrospective of artists’ shiny silver balls.

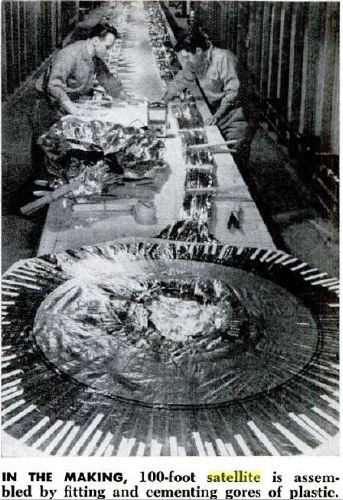

Piene was creating these Light Ballet pieces while the Echo I satelloon was orbiting the earth, its reflection visible to the naked eye. He exhibited them in New York in November 1965, at the Howard Wise Gallery. Sperone has reprinted Piene’s essay from the small catalogue to that show. Here is an excerpt:

In 1959 I played the light ballet with hand lamps, in 1960 I built the first machines, in 1961 they appeared in large darkened rooms at exhibits and in museums: one object, two objects in a large hall, a waste of space, an elimination of conventional attitudes about quantity. The farther the distance between the projecting device and the light-catching confines of a room, the larger are the light forms. And when they are large, the claustrophobia caused by the ordinary cubicity of our interior spaces recedes.

…

My endeavor is twofold: to demonstrate that light is a source of life which has to be constantly rediscovered, and to show expansion as a phenomenal event. Everything is striving for larger space. We want to reach the sky. We want to exhibit in the sky, not in order to establish there a new art world, but rather to enter new space peacefully–that is, freely, playfully and actively, not as slaves of war technology.

A rubber skin, helium and the wind, light, electricity and fireworks seem to me excellent media. The revolving beam of a lighthouse and a balloon in the air are more convincing sculptures than the big chunks that are so hard to move. Calder’s mobiles can be taken apart. Our objects ought to be inflated or ignited or projected. And environments? As far as a laser beam reaches. Are the jet pilots who write vapor trails in the sky the artists of our time, as Gothic stone-masons were the artists of theirs?

Despite their similar shapes, there is one essential difference between Gothic cathedrals and rockets: a cathedral seems to soar, expressing the yearning of its builders to ascend to heaven; a rocket does soar. The same technical difference exists between traditional sculpture and my objects. Previously paintings and sculptures seemed to glow, today they do glow, they are active, they give, they do not merely attract the eyes, they do not merely express something, they are something. A filament glows and warms, a painted halo only reflects light. Energy in a contemporary form produces the living media. Is the filament in itself a piece of art?

Transformation still has two meanings, one technical, one spiritual. He who leaves his house leaves the light on to make it appear inhabited.

Previously: Otto Piene et al’s Centerbeam & Icarus on The National Mall