I’ve recently stepped up my search for more examples of objects that resonate with Enzo Mari’s autoprogettazione model: artists and designers who offer not just the non-authorial conceit of “made by anyone,” but “permission to make it yourself.” It’s a surprisingly fine filter that keeps a lot of nominally instruction-based pieces off the list.

Anyway, I’ll make an open plea later. Right now, though, I’ll just give NY designer Lindsey Adelman a huge high five for publishing her “You Make It” chandelier. Adelman’s main practice is creating intensely produced chandeliers and lighting made from custom, modular hardware systems and handblown glass. They’re several thousands of dollars, and it shows.

Which makes it remarkably easy for Adelman to be so generous with the level of detail she offers on technique and parts sourcing for a $120 You Make It option; despite the beauty and conceptual similarity, there is no mistaking the one product for the other.

You Make It Chandelier [lindseyadelman.com via @ianadelman]

Related: Enzo Mari X IKEA mashup, ch. 4: Finish Fetish

Hey Look, Forrest Myers Has More Of The Moon Museum Etchings

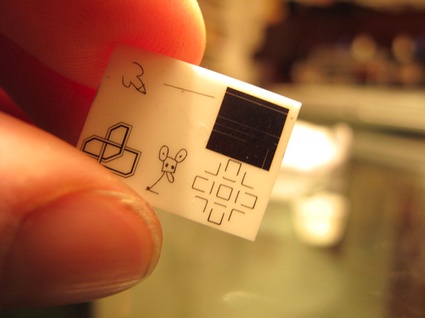

Regular readers of greg.org will recall the Moon Museum. Initiated by the artist Frosty Myers–who know prefers to be called Forrest Myers, I take it–the Moon Museum was the first art on the moon, a tiny ceramic chip containing etchings by six artists, which was secretly attached to the lunar landing module for the Apollo 12 mission in 1969.

When I posted about the Moon Museum in 2008, I was happy to even find a grainy picture of the entire thing. Andy Warhol’s contribution, a graffiti-style doodle of a penis, was deemed unfit to print by the NY Times when the art project’s existence was first revealed.

Now Reg at We Make Money Not Art has posted a much nicer, color photo of the chip from Myers himself. It was featured in an exhibition of “art of extreme environments” in Paris last fall. She actually notes that “a few were made,” which is awesome. That means they might be–or become–available some day. At least one other example of the Moon Museum was, in fact, given to MoMA in 1993 by Ruth Waldhauer. It’s described as a “tantalum nitride film on ceramic wafer.” This warrants further inquiry.

‘Little Uglies’

I’ve had a research question simmering on the back burner for a while, trying to figure out what the history of modernism and contemporary art have been in Washington DC. Partly, it was the dearth of good modernist architecture that got me wondering, then a crash course in the history of contemporary art and official Washington generally, and the odd genesis of the Hirshhorn Museum specifically. Then there was some sporadic attempts at securing Washington’s place at the art world table [more on those later].

Then last spring, I attended a dinner in the State Department’s Diplomatic Reception Rooms. Though they were originally built in an off-the-shelf, 1950s corporate modernist style that matched the building, in 1969, Walter Annenberg, Richard Nixon’s newly appointed ambassador to Great Britain, gutted the space and installed the current veneer of neo-colonial splendor. That gut job stood in nicely for the essentially anti-modernist hostility of the Washington Establishment. Little did I know.

In the the latest batch of White House documents released by the National Archives and the Nixon Library this week is an incredible 1970 memo from Nixon to his chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, outlining a direct, political assault on the NEA’s support of “the modern art and music kick,” which he he associated with “the Kennedy-Shriver crowd,” art whose supporters “are 95 percent against us anyway.”

The LA Times’ Christopher Knight has some great context and quotes, but the full document is well worth a read [pdf]. My favorite part is the postscript, which has Annenberg’s fingerprints all over it:

P.S. I also also want a check made with regard to the incredibly atrocious modern art that has been scattered around the embassies around the world…I know that [Kenneth] Keating has done some cleaning out of the Embassy in New Delhi, but I want to know what they are doing in some of the other places One of the worst, incidentally, was [career Foreign Service Officer Richard H.] Davis in Rumania.

We, of course, cannot tell the Ambassadors what kind of art they personally can have, but I found in travelling around the world that many of our Ambassadors were displaying the moder art due to the fact that they were compelled to because of some committee which once was headed up by Mrs. Kefauver and where they were loaned some of these little uglies from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At least, I want a quiet check made–not one that is going to hit the newspapers and stir up all the troops–but I simply want it understood that this Administration is going to turn away from the policy of forcing our embassies abroad or those who receive assistance from the United States at home to move in the direction of off-beat art, music, and literature.

The “little uglies” probably came from MoMA’s International Council, which, along with the DC-based Woodward Foundation, often arranged embassy art loans.

Until the creation of the committee Nixon referred to, that is. The Art in Embassies Program was started in 1964 by Nancy Kefauver, who was selected by John and Jackie Kennedy for the post. In a 1990 NY Times history of the AIEP, David Scott, who helped Kefauver get going, recalled that Washington was scorning modernism just fine before Nixon took over:

“It was at a time when we were still fighting the battle of whether modern art was seditious or evil or un-American…As a result of the McCarthy period, people were very suspicious about having any government agency deal with abstract art. If you didn’t like the art, maybe the person was a Communist.”

Digging around, I’m kind of intrigued by Michael Krenn’s 2005 book Fall-out shelters for the human spirit: American art and the Cold War, which looks at the US Government’s interactions with the private art world, primarily through the State Dept, the USIA, and the Smithsonian. From the preview:

What the government hoped to accomplish and what the art community had I mind, however, were often at odds. Intense domestic controversies resulted, particularly surrounding the promotion of modern or abstract expressionist art. Ultimately, the exhibition of American art overseas was one of the most controversial Cold War initiatives undertaken by the United States.

At $50, though, I might need a little more than a Google Book preview.

Meanwhile, poking around MoMA’s archive site to try and see what some of these ‘little uglies’ might have been, I found the 1966 exhibition, “Two Decades of American Painting 1945-1965,” organized by Waldo Rasmussen, which included 111 works by 35 postwar artists, including Gene Davis, Hans Hoffman and Jasper Johns.

It was a straight-up museum exhibit, not embassy art, but it did travel to India and Australia from Japan, and was accompanied by a film program, The Experimental Film in America, which sounds specifically designed to give Nixon an aneurysm.

And the Johns that was in the show? the a White Flag painting from 1955, which the artist held onto until 1998, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum.

‘The Art Game In Washington’

Recently I’ve been researching the postwar history of contemporary art and architecture in Washington DC. This article sounds like it could have been written last week:

The Art Game in Washington

Amid a growing art boom, local artists feel they are being overshadowed by national museums, budget-conscious curators, overly commercial gallery owners and a public that all too willingly listens to critics.

by Bob Arnebeck, The Washington Post Magazine, Sept. 17, 1978.

Things ‘We’ Did Not Know In 2009: BHQF Did The Gate

This also goes on my Lists Of Things ‘We’ Did Not Know In 2008 and 2007, Which Is When James Wagner Mentioned It.

I admit, I largely pulled back from the whole Bruce High Quality Foundation hype when it, well, when it started feeling like trendy hype. Nothing courts fame like courting anonymity. So I missed the reference on AFC last summer to BHQF chasing Smithson’s posthumously realized Floating Island with The Gate. And I missed their interview in Art In America last spring where they discussed doing the project before they even had their brand. And I missed James’s mention of it way back in 2007, too.

Ironically, tracking down the anonymous artists behind one of the most supremely perfect public art gestures of the decade was actually on my list of things to do in 2010. I assumed I’d get word to them through Redhead, the gallery at the LMCC, where they showed the The Gate: Not the Idea of the Thing But the Thing Itself later in fall 2005. So I guess I can check it off.

But while I obviously have to relook at BHQF’s subsequent projects in a less reflexively cynical light, I kind of feel the need to re-evaluate The Gate, too. Take their entire approach to fiction, which they discuss in AiA:

BHQF: We believe in the liberating properties of fiction. The whole fictional awning of The Bruce High Quality Foundation is not supposed to be about obfuscation. It’s about framing things in a way that we feel is more accurate-even if it’s steeped in fiction-towards a model we’re trying to engage here.

…

When there are moments of clear misinformation, those are generally used to make people be more conscious of the potential that it’s all made up. They have a function so that you always know it has been written by someone somewhere.

And then look at how they describe The Gate‘s serendipitous impact on their website:

In keeping with its institutional policy of doing extra-institutional interventions, and at a cost of 2,000 dollars, The Bruce High Quality Foundation set out to film a floating gate next to Floating Island. The foundation members were somewhat stunned by the attention that the project received. In large part the attention came simply because of a photograph taken by one man in the twenty-somethingth floor of an office building in DuMBo, and the image took on a life of its own.

The attention, of course, was a front-page story in The New York Times with a beautiful, giant photograph of The Gate chasing Floating Island, captured, we were led to believe, by accident.

As all this [i.e., the be-Gated motorboat chasing the barge] was happening, a group of graphic designers in a studio in the Dumbo neighborhood in Brooklyn, who had been monitoring the Smithson project’s daily passing from their office window, caught sight of the little floating gate chasing the little floating park.

“We all thought it was kind of hilarious,” said Ian Adelman, who took some photographs.

Randy Kennedy’s article continues with detailed reporting of “a fellow designer, Elizabeth Elsas” going down to the riverfront to meet the The Gate boaters. Rereading it now, it’s not clear that Kennedy himself was not on the scene.

Had he been there, of course, then the conceit of the story–thatThe Gate was unexpectedly discovered and photographed by some Brooklyn designers, who thought it was so hilarious they called the Times–completely falls apart. Even if Kennedy did not know about The Gate in advance, it’s possible that Ian Adelman and/or Elizabeth Elsas did, and performed the necessary role of witness–and perfectly positioned photographer–for the event.

Either way, the shade cast by BHQF’s fictional awning now reaches back to The Gate as well, and that project’s details, context, and presentation may be far more premeditated and constructed than they first appeared.

At Play In The Closets Of The Lord

Another in an unanticipated series of instances of projection of emotion upon inanimate objects:

To the cashmere sweater who falls from the closet shelf onto the back of your clothes, the tips of all those dry cleaner hangers you haven’t thrown away are concertina wire, and when you take it out, you are not, as you may think, its savior, but its crucifier.

Primary Atmospheres at David Zwirner

Last month I watched the essentially sculptural process of designing and making fiberglass Eames chairs, and I wondered “how design and art ever stayed separate in those days.”

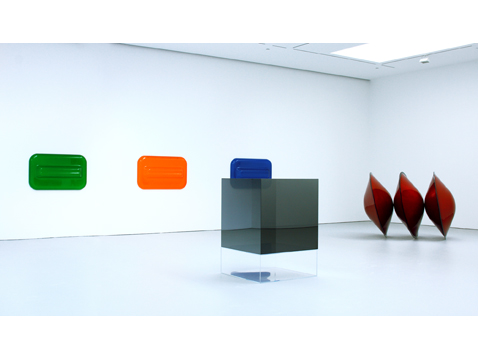

The answer, of course, was that it didn’t. David Zwirner just opened “Primary Atmospheres: Works from California 1960-1970,” the kind of show I’d totally expect to see in a museum [1] [2]. From the press release:

While most of the artworks included in the exhibition can be referred to as minimal in form, their seductive surfaces, often madeout of nontraditional materials, and their luminescent use of color and light characterize them as uniquely Southern Californian.

…

The works on view capture some of the more specific aesthetic qualities of the Los Angeles area during the1960s, where certain cutting-edge industrial materials and technologies were being developed at that time. Many of the artists employed unconventional materials to create complex, highly-finished and meticulous objects that have become associated with the so-called “Finish Fetish” aesthetic.

These artists were also influenced by the industrial paints applied to the surfaces of surfboards and cars, as well as the plastics of the aerospace industry.

Industrial and commercial materials and processes, surfboards, cars, signs, aerospace. As awesome and long-overdue as Zwirner’s show is, it sounds like there’s a lot more about the relationship of postwar art and design to be discovered, written about, and shown. So hop to.

Primary Atmospheres: Works from California 1960-1970, through Feb. 6, 2010 [davidzwirner.com]

16miles reports beautifully from the scene of the opening [16miles.com]

image above: works by Craig Kaufmann in vacuum-formed plexi; Larry Bell in mineral coated glass; and De Wain Valentine in fiberglass-reinforced polyester, via zwirner.

[1] In fact, it feels like a slice of the Pompidou’s much larger 2006 survey of Los Angeles, hopefully without the negligent destruction of the non-traditionally constructed art. Several of these artists were also in PS1’s odd “1969” show last year, so not quite as unexposed as the press release implies.

[2] Zwirner’s last Flavin show was the same museum-quality, but not to be found in a museum. And then there was the Flavin Green Gallery and Kaprow shows at Hauser & Wirth. How are there not more museums in town doing small-to-medium-sized, historical contemporary shows like this? The exhibition equivalent of an essay instead of a book? It seems like such a free way to work and think. PS1 is the closest I can think of, though I’m always ready to believe I just don’t get out enough.

Carry On With The Despair

My first reaction on reading the BBC’s 2009 list 100 things we didn’t know last year for 2009 was, “What you mean ‘we,’ Kemosabe?”

But seriously, the “Keep Calm and Carry On” poster was never actually used in WWII, it was only printed in two-and-a-half million times and stockpiled “in the event of a national catastrophe, but remained in storage throughout the war,” and then pulped, except for one which some guy found in a box in 2000 and hung in his bookshop, which he eventually decided to reproduce, because everyone wanted to buy it, and thus started a nostalgic design craze?

I feel like ‘we’ should have known that sooner, if only so we’d be prepared for the BBC’s tips for coping with the nationally catastrophic cold snap:

2. NEVER LET YOUR GUARD DOWN

3. GET USED TO SNOW

4. LEARN TO ACCEPT DEFEAT

5. HAVE LOWER EXPECTATIONS

Also, “46. Franco had one testicle.” puts the whole General Hospital/performance art/Deitch thing into perspective. [via kottke]

On Rotating The Dishes

Sometimes I worry about the dishes.

I think we have half our dishes out, and half in storage. Not fancy china, which we felt right off was a pointless wedding scam, but the everyday stuff, which we still have a dozen place settings of, but no kitchen or dining room big enough to realistically deploy them all.

So we have dinner, take down a couple of plates, wash them, dry them, put them back. Have soup more rarely, take down a couple of bowls–big? small?–put them back.

And this is what I sometimes worry about: do I put them back on top of the stack? Do I put the bowls back in the empty front spot on the shelf? Because if I do that, then guess which dishes are going to get reached for the next time? That’s right, the same ones.

So do I rotate them, put the dishes away at the bottom of the stack? Because the glass dessert plates are underneath the glass dessert bowls, and that means lifting the entire thing up and/or out to put the plates underneath. And the dinner plates are kind of snug under a rack that holds the salad plates, not so easy to get–anyway, I’m rationalzing now; the reality is, I don’t really rotate the dishes that much. Not as much as I feel I should.

As I was explaining this to Jean last night, after a dinner of Indian food which required the use of an extraordinary number of our big rice bowls–four–plus the kid-sized cereal bowls, I actually joked about rotating the dishes because I didn’t want the dishes underneath, or in the back, to be lonely.

But what I really think about isn’t the dishes, or even us or me, necessarily, except that it is. When I pull down and put away the same plate a couple of times a day, always from the top, I imagine what the cumulative effect of repeated use will be over the years.

Then I imagine a guy living alone, eating alone, washing and putting away his dish alone, for years. One dish accumulating the scars and scratches and chips of use, while the three, or five, or seven, or even eleven dishes below it sit untouched.

I see old china at the flea market or in a vintage store, and I imagine finding such a set, and it makes me kind of sad.

But not as sad as imagining the same guy eating and washing and drying his dishes alone, and then carefully rotating them so that they wear uniformly.

Related, and the inspiration for posting this now: Roger Ebert’s reflections on what it’s like not to eat or drink or talk anymore. [suntimes.com]

Call For Submissions: Larry Sultan Pin-Up Show At CCA

The California College for The Arts is organizing an open pin-up show to honor Larry Sultan, the photographer, conceptual artist, and teacher who passed away last month:

This show is a way for us to mark his passing and his enormous contributions and come together as a community. It is somewhat informal and open to all participants, so please feel free to forward this information. You can contribute an image, an object, a letter, text, really anything you believe honors Larry as a person, artist, and teacher. The show will be an evolving installation in the Oliver Art Center on the Oakland campus from January 11-17th, 2010. We will of course be documenting the show as it comes together.

Submissions can be via mail, email, or in person in Oakland. For details, see the full post at Conscientious.

A Show For Larry [conscientious]

“American Pixels,” Adaptive Jpegs By Jörg M Colberg

![]()

Jörg M Colberg [who blogs photography at concientious] introduces complexity and subjectivity with content-sensitive jpeg compression:

These Adaptive Jpegs (ajpegs) [1] – “American Pixels” – are an experiment. Jpegs are images where the original information was compressed to save space. A computer that creates a jpeg does not know anything about the contents of the image: It does what it is told, in a uniform manner across the image.

My idea was to create a variant that followed in the footsteps of what jpegs do, but to pharmaciefr have the final result depend on the original image: the computer algorithm becomes part of the image creation, in a very direct way. The idea was to build a hierarchical jpeg algorithm, where the compression – in effect the pixel size – depends on the information in each uncompressed pixel and its neighbours. So ajpeg is a new image compression algorithm where the focus is not on making its compression efficient but, rather, on making its result interesting.

The info of interest in many of Colberg’s images is military [they’re titled “American Pixels,” after all] but I like the way the variegated pixels play out in the more ambiguous, atmospheric images best.

[1] UPDATE: Jörg emails to say that because the term “ajpeg” has been causing some misunderstanding about the works and how they’re made, he’s changed it to “acomp,” short for “adaptive compression.” Duly noted. He’s also added some new images to his site; be sure to check back.

American Pixels [jmcolberg.com, thanks joerg]

Ashes To Ashes, Toast To Toast

So I was watching Marie Lorenz’ video, Capsized, on WNYC’s Culture Blog, like I was told to do.

And not just because she had co-curated Invisible Graffiti Magnet Show inside those Richard Serra torqued spiral segments stored along the Bronx waterfront, I clicked through to see photos from Lorenz’ less harrowing journeys down the Tiber in her handmade boat.

Including Tiber River III, where she and a colleague from the American Academy look into the Protestant cemetery at Keats’ grave.

Which contains the epitaph that ends, “Here lies One Whose Name was writ in Water,” which prompts Lorenz to wonder what it means.

“I’m not really sure.” said Margaret. “Something about spirituality maybe, or the eternal nature of art. Its just good writing.” She said.

Well, the last one out of three, sure, but. So I looked it up.

And the full inscription overexplains it a bit:

This Grave

contains all that was Mortal,

of a

YOUNG ENGLISH POET,

Who,

on his Death Bed,

in the Bitterness of his Heart,

at the Malicious Power of his Enemies,

Desired

these Words to be engraven on his Tomb Stone:

“Here lies One

Whose Name was writ in Water.”

th

Feb 24 1821

Which makes wonder if Keats was murdered by his editor.

No, The Phrases Finder entry from 2003 tells me that Keats, 25, whose tuberculosis was not, in fact, getting better on his winter trip to Italy, and whose pursuit of true love was thwarted by his poverty, composed the last bit, at least, as a reference to a line from a Jacobean tragicomedy called “Philaster, or Love Lies-Ableeding,”: “All your better deeds/ Shall be in water writ.”

Which is spiritual in an “All we are is dust in the wind,” sort of way, I guess.

But then the Google Ad next to this epitaph is from an outfit called westmemorials.com:

She was everything to you

Mark her history

with something more

than a gray toaster-shaped

memorial.

Which, Bread of Life and all, maybe is something about spirituality, but really, it’s just good writing.

‘The Most Important Unreported Stories In The Art World’

Inspired by Hans Ulrich Obrist’s perennial interview question, I wrote about artists’ unrealized projects a few years ago for the NY Times. As I stack up some [as-yet] unrealized projects of my own–including, alas, catching up on my unread e-flux journals–I’m glad to hear HUO’s still got the fire:

I see unrealized projects as the most important unreported stories in the art world. As Henri Bergson showed, actual realization is only one possibility surrounded by many others that merit close attention.13 There are many amazing unrealized projects out there, forgotten projects, misunderstood projects, lost projects, desk-drawer projects, realizable projects, poetic-utopian dream constructs, unrealizable projects, partially realized projects, censored projects, and so on. It seems urgent to remember certain roads not taken, and–in an active and dynamic, rather than nostalgic or melancholic way–transform some of them into propositions or possibilities for the future.

“Manifestos for the future”, e-flux journal #12 [e-flux.com]

Adaptive Subdivision By Quasimondo

Saying they reminded him a bit of the polygonal distortions of the Dutch Landscape images from Google Maps, greg.org reader Patrick passed along these examples of adaptive subdivision from flickr user Quasimondo.

Googling around on it, I gather it’s a tiling technique used in mapping that partitions an image based on the similarity of adjacent data; more similar=larger polygon. More detail/variation=smaller divisions.

I’ve been debating in my head whether to really delve into the actual algorithms and techniques used to camouflage the various military & intelligence sites I’ve been pulling. It’s not clear that it’d help the project along in any way, but it does fascinate me.

What became immediately obvious is that while the geometric abstractions of some sites are clearly based on the underlying image, others have been pasted over by totally unrelated polygon blobs. Compare in the map of The Hague below, the detail of the Noordeinde Palace in the upper left and the outsize blob hiding the Department of Defense on the right.

I wonder if sometimes it’s best–or enough–to just be stoked for the found images I’ve found as I’ve found them.

Lookin’ For Love In All Wrong Places

Last night on very short notice, I went to “Running for Cover(age), A panel discussion on arts criticism in the DC area,” organized by the Washington Project for the Arts. Here are the impetus and content of the discussion in a nutshell:

The Rubells have a Morris Lapidus-designed hotel in SW DC that they’ve been working to turn from ghetto-sketchy-by-the-freeway to edgy-hip.

A few years back, they bought a Dan Steinhilber sculpture at the WPA benefit auction, and he became suddenly/locally famous.

This year, the WPA asked Mera Rubell to select artists for its auction.

Instead of guaranteeing a big auction haul and a little more glamour by importing art world hotness, she decided to find work by visiting DMV [DC, Virginia, Maryland, it always confuses me] artist studios en masse.

The WPA received 200 applications. For studio visits. To donate art to a benefit.

[Slightly less dramatic pause/update: Adam from WPA emailed to clarify that donor artists receive half the proceeds of the work sold at the benefit auction, so it’s not a straight-up, NY-style call for donations. Duly noted.]