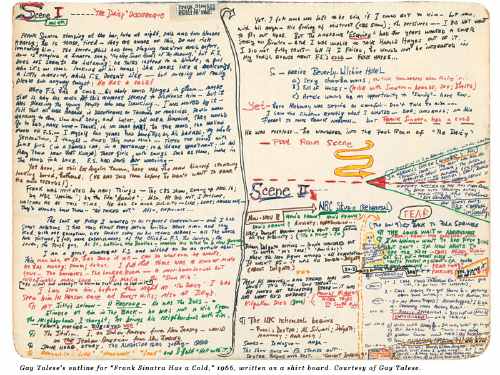

Gay Talese writes everything everyday on shirtboards—

INTERVIEWER

Do you use notebooks when you are reporting?

TALESE

I don’t use notebooks. I use shirt boards.

INTERVIEWER

You mean the cardboard from dry-cleaned shirts?

TALESE

Exactly. I cut the shirt board into four parts and I cut the corners into round edges, so that they can fit in my pocket. I also use full shirt boards when I’m writing my outlines. I’ve been doing this since the fifties.

INTERVIEWER

So all day long you’re writing your observations on shirt boards?

TALESE

Yes, and at night I type out my notes. It is a kind of journal. But not only my notes–also my observations.

INTERVIEWER

What do you mean by observations?

–including the outline for the Greatest Magazine Article Ever?

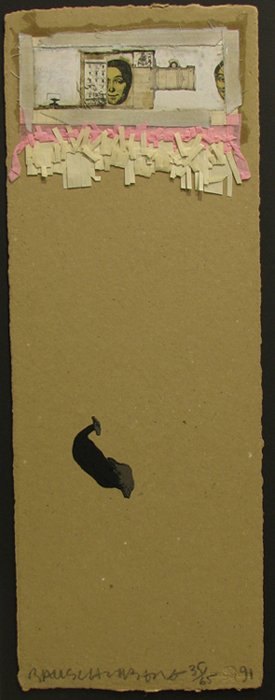

Robert Rauschenberg developed his abstract/pop collage techniques on shirt boards, while traveling to Italy and Morocco with Cy Twombly in 1951-3. The pair [couple?] of young artists fresh from Black Mountain College were traveling on Twombly’s grant money, which meant Rauschenberg had next to nothing to buy art materials with.

Robert Rauschenberg developed his abstract/pop collage techniques on shirt boards, while traveling to Italy and Morocco with Cy Twombly in 1951-3. The pair [couple?] of young artists fresh from Black Mountain College were traveling on Twombly’s grant money, which meant Rauschenberg had next to nothing to buy art materials with.

So he collaged cheap prints, newspaper, feathers, drawings, and random stuff onto the shirtboards from their laundry in an irreverent twist of his teacher Josef Albers’ technique.

In 1990, just as Walter Hopps’ incredible show, “Robert Rauschenberg the Early 1950s” was preparing to debut at the Menil, the artist collaborated with Styria Studio to produce meticulous replicas of 28 of the shirtboard works in an edition of 65.

Within the first five minutes of walking into the Menil for the first time, I met Cy Twombly standing in front of his chalkboard painting in the lobby. He had just completed his interview for Hopps’ catalogue. Needless to say, I made it back to Houston for the opening, and then saw the show multiple times at the Guggenheim SoHo.

Beyond instilling a deep appreciation for Rauschenberg’s interest in abstraction and conceptualism both, that show changed the way I look at shirtboards forever. Not that I’ve ever done anything about it, of course, just that it hits a nerve. What’s worse about Gay Talese: he lives in my old neighborhood, so we might even share a shirt laundry.

a nice discussion of the Shirtboard works [icallitoranges]