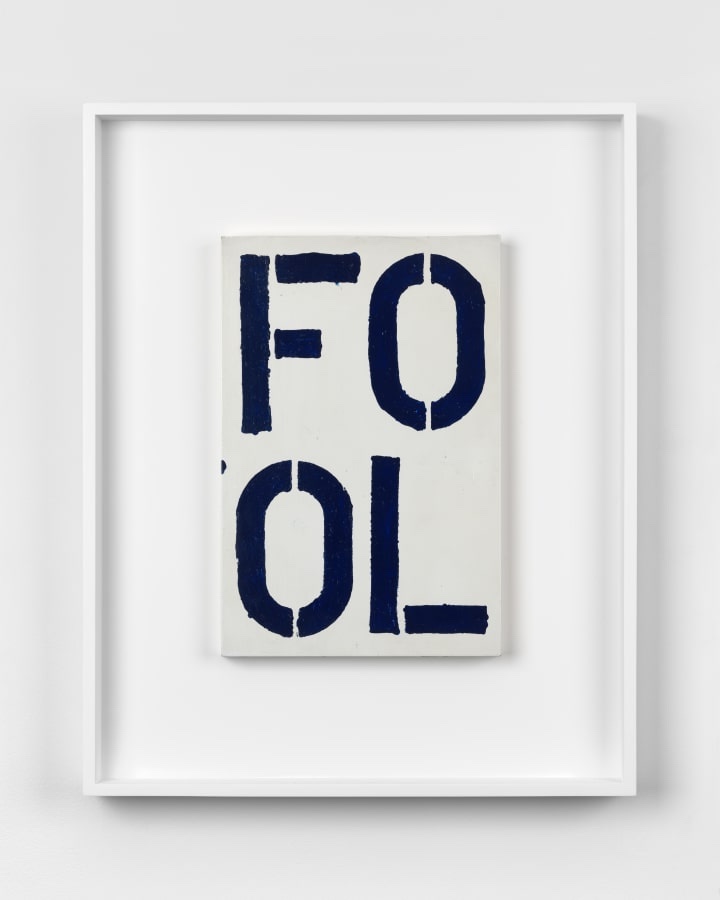

Here are some things that are larger than this untitled 2004 Rachel Harrison sculpture:

my iphone

my 15yo SonyEricsson k790i smartphone

a box of Altoids

a deck of cards

a Metrocard

a piece of grocery store sheet cake at a Fourth of July block party

a 4×6 inch snapshot overpainted by Gerhard Richter while he’s cleaning up at the end of squeegee day

Here are some things that are about the same size:

a piece of grocery store sheet cake at a Fourth of July block party where a lot more people showed up than expected, and there was only one cake, and they had to stretch it.

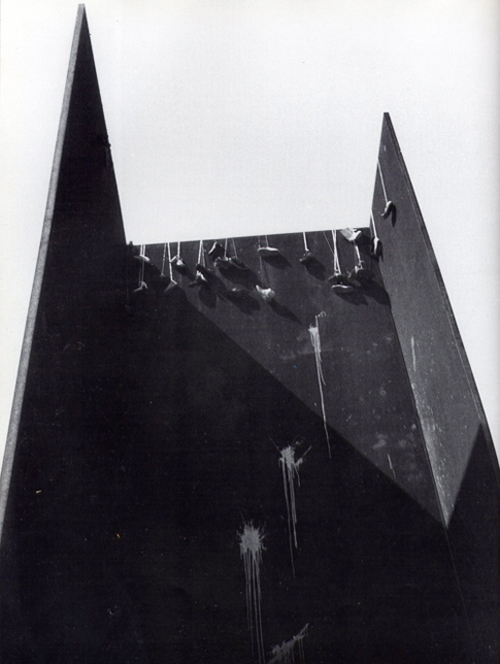

a little piece of polystyrene foam trimmed off the end of a larger sculpture, or maybe the leg, now laying around the studio where a work like Hey Joe [below] is being made.

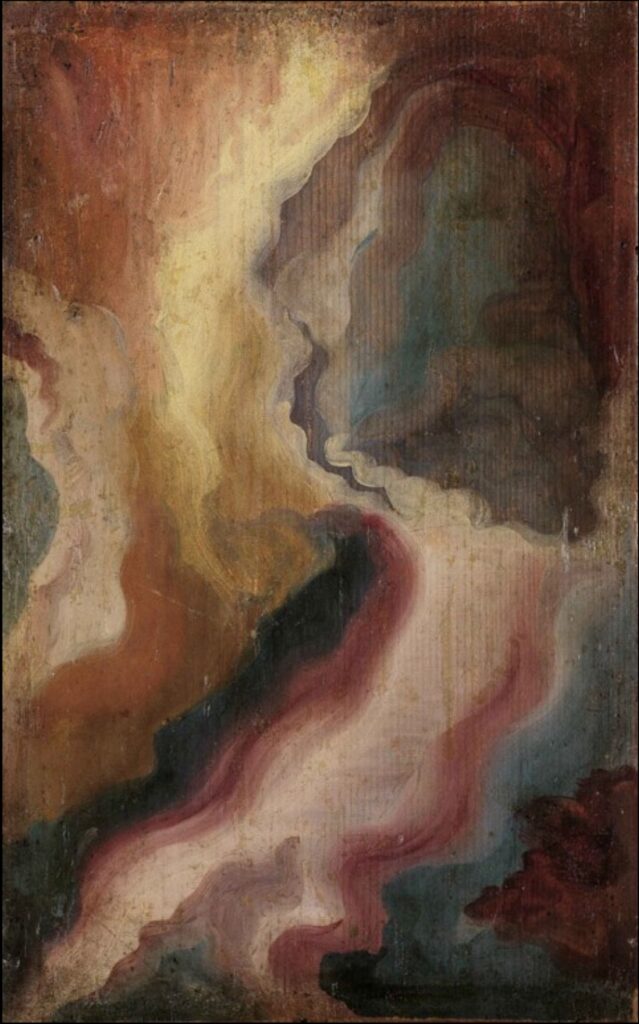

That’s the second reference to works that sound like castoffs or afterthoughts of some ostensibly more important studio activity, but I do not think that’s what Untitled actually is. I count ten colors of paint, in multiple layers, on every sculpted surface, plus the bottom, plus some fur, and a flag. This is a little object that has seen some stuff. [update: I have heard from the successful buyer of this little object that the fur was dust–which, though also a sign that the work has not been overhandled, is hilarious and gross–and has been removed.]

Here are some things that are about as small that have also seen some stuff:

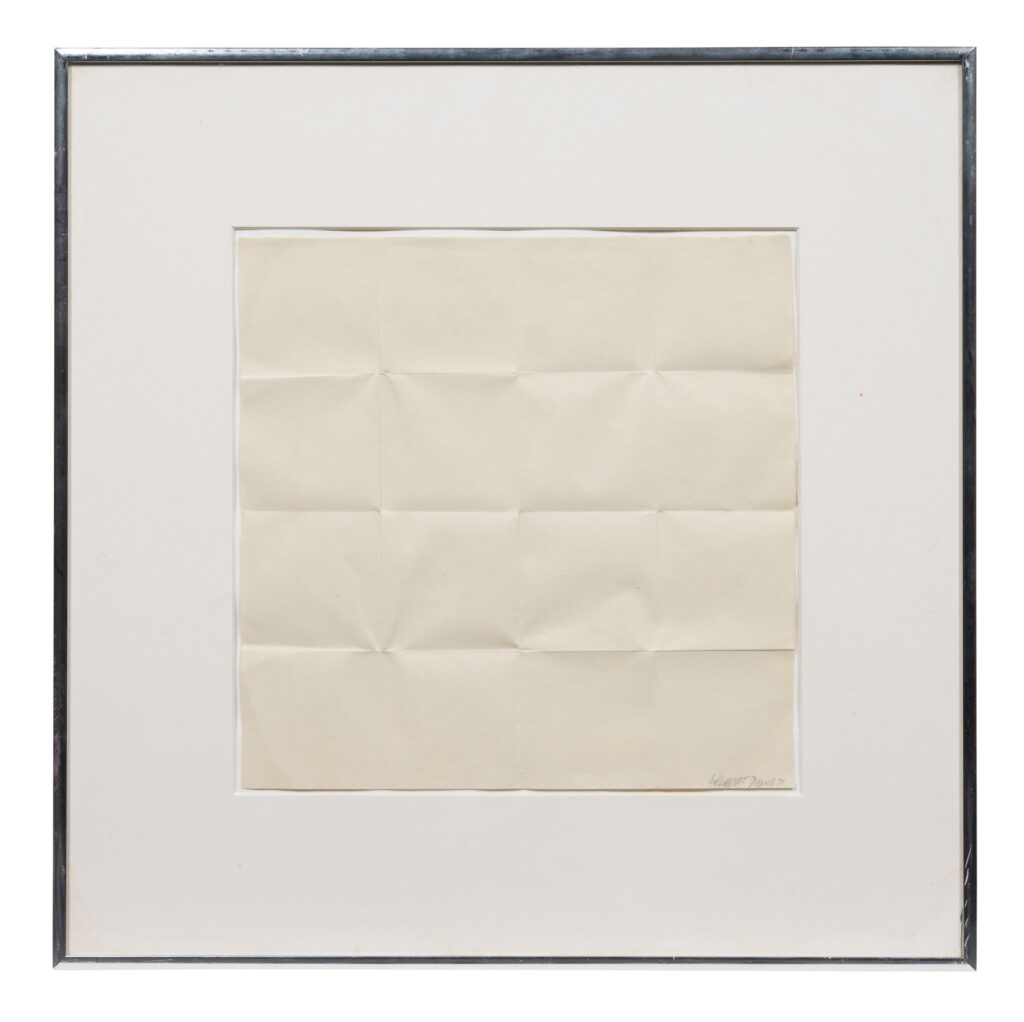

a 1937-39 Giacometti literally titled Very Small Figurine, from the era when he supposedly said he fit all his sculptures into a matchbox as he fled across the Alps.

And one of my absolute favorite things in the entire Jasper Johns Catalogue Raisonné, a tiny flag embedded in wax in a little frame, from 1958, which he gave to Merce Cunningham, and which had never been exhibited before 2014.

Whatever brought this Harrison into existence and out of the studio was not the market, or the demand for a show, but something else. Whether it was a private gesture or a gift or some daily or exceptional practice, I don’t know, but it is interesting. This is the point where I wonder if I should hold off on posting until I try to get this, or where I say, if I don’t get it, I invite whoever does to give it to me. I mean, it’s meant to be a gift, isn’t it?

June 4, 2021, Lot 670, Rachel Harrison, Untitled, 2004, est. $1,500-3,000 [update: sold for $2,700, not to me] [stairgalleries]