Thanks for the support and feedback on the Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents &c., &c. book. [updated link info below]

Some folks who ordered the electronic version–the first to get the compilation in their hands, since the print editions take a few days to arrive–have emailed wondering where “the rest” of Richard Prince’s deposition transcript is, because there are gaps and missing pages.

That’s exactly right, and it’s why I decided to make this thing in the first place. As far as I can tell, the entire 378-page transcript of the 7-hour deposition was not entered into the court record, only the excerpts that pertained to quotes or points referenced in the two sides’ various legal motions. As I was reading those scattered snippets in various places in the court record, I realized it would be more useful to have a single compilation of all Prince’s testimony. And it’d be easier if it was in order. So I took apart the pdfs and sorted the pages, then interlaced the other exhibits [i.e., images from Cariou’s book and Prince’s show and catalogue] as they came up in the course of testimony.

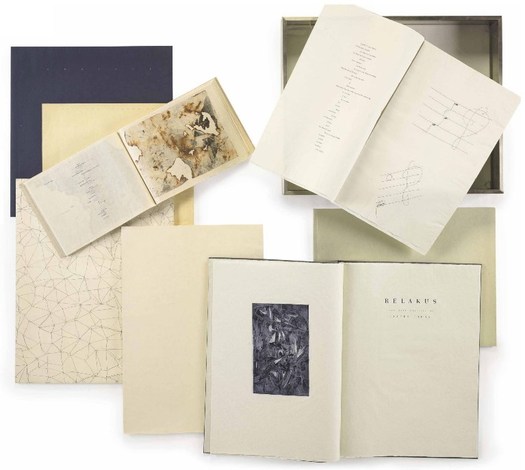

Here are a couple of sample spreads taken from my original [sic, heh] pdf. There are about 250 of these transcript pages in total, four per printed/pdf page.

pp. 125-8, 149-152

pp. 178-181 and Exhibit 15, installation shot at the Eden Rock Hotel, St. Barth’s

APR 2011 UPDATE: Here is the link to buy the new, expanded edition, which includes Prince’s entire deposition transcript–an additional 101 pages–plus other key legal documents. It’s a new printer, and the finish of the book is nicer, I think.

Category: art

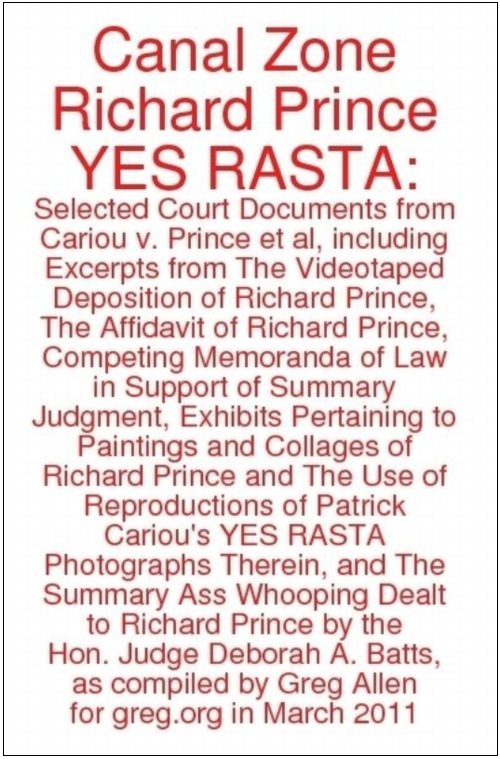

Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: The Book

from greg.org: Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents, &c., &c. in

hardcover, 290pp. $24.99 [updated link info below]

Because really, why not?

It’s always bugged me when I read a news story about a legal case, or a scientific report, and there’s no link to the original source material. And since I’ve been quoting from them a lot lately, I have been fielding a lot of requests for copies of the court filings and transcripts in the Patrick Cariou vs. Richard Prince & Gagosian case.

It was yesterday afternoon, though, when I was sending my fourth email [or eighth, since the attachments are so big] that I realized Richard Prince’s deposition is not only the longest interview he’s ever given, it’s probably the longest interview he’ll ever give. [Go ahead, Hans Ulrich, you just try!]

I mean, seriously, the guy talked for seven hours. Under oath. In insane detail about his work, process, and ideas. Granted, he was being grilled by a guy whose art ignorance is only surpassed by his obvious contempt for Prince, a lawyer who can’t tell a photograph from a painting from a reproduction in a book. But still, he got Prince talking.

And Prince was surprisingly [to me, anyway] and admirably consistent and credible, at least in terms of his work. Yeah, it’s a nice bit of fact-checking trivia to strip away the coy mystery crap that surrounded his Guggenheim retrospective: Prince testified that he is Prince, and that he did live in the Panama Canal Zone, but only as a very young child.

But I found his explanation of his early formative inspirations, particularly Warhol and punk rock, to be both relevant and sincere. The deskilling argument that you could pick up a guitar for the first time, and by the end of the week, go up on stage and perform, with visceral effect, sounds real to me. It makes sense, at least in its own context [and in my own high school experience.]

The cover of the paperback edition includes the full title. 290pp 376pp, $17.99

Anyway, Prince’s entire deposition transcript has not been released [update: it has now; see below], but a patchwork of 250 or so pages out of about 375 were attached as supporting documents to various filings and motions in the case. So I sifted through and pulled them all out, and then placed them in numerical order. There are a lot of gaps, of course, and legalistic joustings, but there’s a lot of information, too.

Combined with his 28-page affidavit, it really is the most extensive discussion of his work, practice and biography I’ve ever seen Prince make. The fact that it’s all coming out in the context of a copyright infringement lawsuit is really too perfect to pass up.

Into this I wove the major documents and exhibits Cariou’s lawyers discussed with Prince: all the Canal Zone series paintings; installation shots from the Eden Rock hotel in St. Barth’s; Prince’s “Eden Rock Pitch,” a rough movie treatment whose characters and story fed into the paintings; and Cariou’s extensive visual comparison of Prince’s Canal Zone paintings and the YES RASTA images that ended up in them.

And for good measure, I added both sides’ memoranda, where they make their fullest legal arguments for their fair use/transformative use and copyright infringement positions. And of course, I included Judge Batts’ ass-whooping of a ruling.

In all, 290 pages, all taken–appropriated, one could say–from the court record, but organized into a clearer, more readable format. And with a focus, not on an exhaustively documenting the case itself, but on Prince and his work.

If you were to download all of this material from pacer.gov, it’s run you upwards of $24 [$0.08/page]. And then you’d still have to sort it all out. For that money, I thought, you could have a nicely printed book. And so that’s what I did.

There are hardcover and paperback editions, and electronic copies, too, which I haven’t tested yet. I’m still tinkering with the cover design. Both versions are included inside the book, as frontispieces or title pages or whatever, but right now, the b/w cover cover is on the hardcover, and the red, made-with-Preview’s-default-annotation-settings version is on the softcover.

This is definitely an experiment, so any and all feedback is welcome. But if you’re looking for the perfect book to take to spring break, or to class up your summer share, then you have come to the right place. Enjoy!

Buy your own copy of Canal Zone Richard Prince YES RASTA: Selected Court Documents, &c., &c. in or in paperback [$17.99]. [createspace.com]

hardcover [$24.99]

APR 2011 UPDATE: OK, the response to this book really caught me off guard, so I’ve done some more work on it. The new, expanded edition now includes Prince’s entire deposition transcript, an additional 101 pages of testimony not previously released publicly, and several additional key legal documents from each side. In addition, while lulu.com was a quick and decent way to release a book almost instantly, I decided to switch to a higher quality printer for the new edition. The facsimile pages are a little smaller, which I’m still working on, but the quality of the book is noticeably higher. It now clocks in at 376 pages, for $17.99.

T-Shirt All T-Shirt No T-Shirt

Has it already been two weeks since I went to Rirkrit’s show at Gavin Brown? Sheesh. Despite being there on a Thursday, there was no soup, but there were T-shirts. Nick was cranking them out, and I wanted to get one.

But I was stymied, couldn’t decide which of the 24 different sayings I wanted. And since they didn’t have my size anyway [XL, just one X, thank you], I knew I wasn’t ever going to wear it, so. So I got them all. Which Nick thought was amusing. Apparently hadn’t happened before. He gamely offered to crank them out while I talked to Gavin, but we decided it’d be easier to just pick them up later.

Or ship them, since he also still had a stack of orders from the opening. And then I went out of town, and I’m all, maybe I should send a couple of my goons over to the gallery and have them throw the shirts in the back of Gavin’s car and hotfoot them over to me.

Maybe I’d tell them to only give the car back if they threw in a couple of the test shirts and rejects. Less Doughnuts More Courage. I Have Oil At Home.

Richard Prince Decision? You’re Soaking In It!

What with all this Prince in my head, I start seeing and reading and remembering things in relation to the Canal Zone case. For instance:

In conjuring up a meaning for Richard Prince’s Canal Zone work that fit the crime she was convicting him of, Judge Batts cited part of a 1978 essay on Appropriation Prince wrote, which he was asked about in his deposition. 1978!

I feel that I like to get as much fact into my work and reduce the amount of speculation. I believe there’s too much–I like an artwork where that when you see something, like a cowboy or a girlfriend, I mean these are, in fact, true.

Batts decided that this meant Prince appropriated Patrick Cariou’s photos because he was trying to convey the same “core truths” about Rastafarianism as Cariou. But it actually made me think of a quote from Greg Foster-Rice’s essay in his just-released anthology, Reframing the New Topographics, where he discussed the influential early 70s photography show in terms of systems theory, and in particular the system of photography itself:

Photographs, in other words, are distinct from other forms of representation in that their connoted messages are built upon a widely held belief in the medium’s denotative status as an almost perfect copy of the real.

I have to say, I really hated Canal Zone when I first saw it, but the more I study and think about it, I’m coming around. In one sense. Prince was making paintings about photography, and about the different expectations of truth and subjectivity, fact and fiction, each medium embodies. Which is nice.

Then there’s the kicker from Steven Stern’s review of Spiritual America: The Guggenheim Retrospective in Frieze:

Perhaps the key joke for the retrospective is one that appeared in several different paintings: ‘Man walking out of a house of questionable repute, muttered to himself, “Man, that’s what I call a business … you got it, you sell it, you still got it”.’ A museum is, after all, a house meant to settle questions of repute. And this particular museum exhibition was, among other things, a comment on Prince’s clearly impressive ‘business’. Like the one described in the joke, this industry depends on a seemingly magical economy: the slippery way that things that aren’t exactly objects – such as images and sex – get valued. Prince is a connoisseur of such economies. For better or worse, no matter how much he’s sold, he’s still got it.

That is just awesome.

And last but certainly not least, is Pablo Picasso, who Prince cited repeatedly as a model and an inspiration for his work. This quote is from an awesomely forthright talk Frances Stark gave at Mandrake Bar in LA in December 2009 as part of the Contra Mundum series. Ro/Lu, you’re off the hook, but the rest of you out there, are in deep trouble for not telling me about the published version of Contra Mundum I-VII. I’m the big man, need the info. Anyway, Picasso:

“But of what use is it to say what we do when everybody can see it if he wants to?”

The Five Most Ridiculous Things About The Richard Prince Copyright Decision

Paddy and her commenters have already done a pretty good job sorting through the decision in the Cariou vs. Prince & Gagosian case, and there are other folks out there with far more expertise and time than I who are also weighing in.

And while I still think this case is really troublesome for the whole fair use ecosystem as it applies to the art world–or more specifically, to artistic practice–that effect may not be lasting or widespread. Fair use and transformative work are still messy, ambiguous principles, almost by design, and artists are gonna do what artists have to do. And really, Judge Batts’ decision is so poorly constructed, and ignores or misconstrues so many basic facts of the case, that it can’t hold up to the inevitable, coming scrutiny, much less serve as any kind of practical impact going forward.

Still, it’s so awful, I can’t let it go without calling out a few of the most egregious passages, arguments, and errors. So here goes.

1) Cariou’s Photos Are Copyrighted. NO $#%ing DUH.

This is the first section of Judge Batts’ decision, and it has gotten a lot of media mention from the skimming crowd, even though it seems utterly and entirely irrelevant to anything at all. [p.10]:

Cariou’s ownership of a valid copyright in the Photos is undisputed. However, Defendants assert that Cariou’s Photos are mere compilations of facts concerning Rastafarians and the Jamaican landscape, arranged with minimum creativity in a manner typical of their genre, and that the Photos are therefore not protectable as a matter of law, despite Plaintiff’s extensive testimony about the creative choices he made in taking, processing, developing, and selecting them.

Unfortunately for Defendants, it has been a matter of settled law for well over one hundred years that creative photographs are worthy of copyright protection, even when they depict real people and natural environments.

I have looked, and I cannot find any documents where Defendants actually made this ridiculous claim that Cariou’s photos–arty, black & white, published in a book–are not copyrightable. It’s like the stupidest tumblr excuse ever [I found this image on the Internet, so it must be public domain!], not the argument the copyright lawyer for the most powerful art dealer in the world would make. Why is this even in here?

Look, the closest argument/evidence I could find is an exhibit [Doc. 61-1] rounding up dozens of Google Image searches for Rastas and Jamaican jungles and ganja tours, but that was to counter Cariou’s inference that the only way to take pictures of Rastas is to do what he did, and live with them for ten years. [Which, according to his deposition, it turns out he didn’t do, But whatever.]

Wow, is it really 12:30? I’ve gotta get some sleep. OK, we’re back. And what follows is, by any measure, too long.

Continue reading “The Five Most Ridiculous Things About The Richard Prince Copyright Decision”

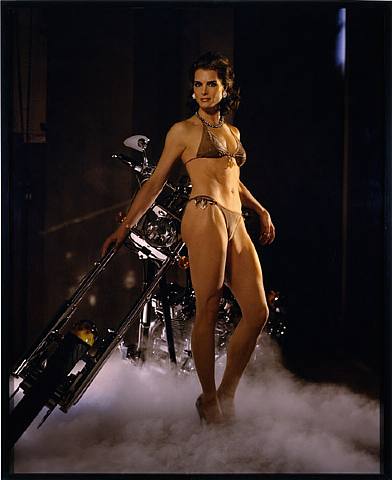

Richard Prince’s Spiritual America

Holy smokes, Richard Prince, Patrick Cariou, Larry Gagosian, Judge Batts, Bob Marley, Richard Serra [! I know, right?], Brooke Shields, $18 million in artwork, the fate of appropriation, the implosion of the gallery system, copyright apocalypse, there’s so much mayhem to discuss, where to start?

Let me cut to the chase here, and focus on the single most important takeaway of the Cariou v. Prince & Gagosian Canal Zone case: he won’t be suing me.

During a deposition, Cariou’s lawyer Daniel Brooks asks Prince about his 2005 work Spiritual America IV [above], for which he appropriated Sante d’Orazio’s photo of an adult Brooke Shields re-staging the 1975 Gary Gross photo of a 10-year-old Shields which Prince rephotographed and showed in 1983, in a temporary storefront gallery he rented on the Lower East Side and called Spiritual America:

Looks Like I Picked The Wrong Week To Give Up Everything

Holy crap, I go away for a long weekend, and what happens?

The death toll in Japan doubles,

The number of meltdowns triples [or something],

We are at war in Libya,

The Death Star has the T-Mobile rebellion caught in a tractor beam,

and Richard Prince somehow lost his open & shut copyright infringement case.

I totally did not see that one coming.

UPDATE: OK, I’ve read through a bunch of the motions, affidavits, and depositions, and the decision [pdf here via aphotoeditor.com], which is basically a flabbergasting shitshow. I’ll probably write a bit more specifically later today, but if it stands, it would have major, sweeping, and stifling effects.

Not only would the current operating assumptions of fair use and transformative use be ratcheted way back, but the contemporary art world would be turned upside down. It would restrict both how artists appropriate, or even refer to, copyrighted work. And it would turn galleries into copyright police, with an affirmative responsibility to clear images, sources, and references for the work they show and sell.

If visual artists and the art market have been operating in some kind of an appropriation bubble, this decision would pop it. Artists would have to adopt the sampling, licensing, and rights clearing practices and infrastructures of the music industry, or the entertainment industry.

But the decision has some glaring omissions and relies rather heavily on almost-20-year-old textbooks and articles from law journals, while ignoring several highly relevant, recent decisions. The most notable ignored precedent is Blanch vs. Koons (2006), which happens to involve another Gagosian artist, and which seemed to set out a workable test of transformative use.

From reading the case materials, including Prince’s detailed descriptions of the making of each of the 29 Canal Zone paintings, it seems obvious to me that Prince and Gagosian were operating under the transformative work/fair use assumptions of Blanch, where changes in scale, medium, context, and color, along with process, editing, collaging, or other process-related elements, are used to identify a transformative work. Judge Batts doesn’t even address process, or any relevance of Blanch to the transformativeness; instead, she makes a blanket assumption that all 29 Prince paintings are infringing because they include Cariou’s Rasta images in some way. It’s really an eye-popping and untenable conclusion.

At the least, the fact that Gagosian the man and Gagosian the gallery were found equally liable for infringing, I am almost certain that this decision won’t go unchallenged. In a series of truly amazing statements, the most shocking is Batt’s cursory finding that Prince, Gagosian, and the gallery all acted in bad faith by not proactively pursuing permission from Cariou to use his images. In other words, operating under the assumption that an artist enjoys a fair use exemption to use or reference a copyrighted element, or that an artist is using copyrighted material in a transformative way, is, on its face, bad faith.

With upwards of $20 million in artwork and unspecified but certain punitive damages pertaining to bad faith actions on the line, there is NO way that Gagosian will let this decision stand.

On the other hand, the photographer crowd is jumping up and down with schadenfreudian glee. [Zaretsky’s rounding up more reactions at The Art Law Blog]

Enzo Mari X IKEA + 6-Year-Old =

So I guess you could argue–and you wouldn’t be completely wrong–that no matter how many coats of hand-rubbed varnish it has, no matter how carefully calculated its design, or how flush its finishing nails, how stainless its many steel screws, a dining table which a six-year-old girl can snap apart like a pair of ramen truck chopsticks cannot, in the end, truly be considered a success.

But anyway, it’s not worth arguing, because that’s what happened the other day. And it’s not important or even relevant to discuss exactly how it happened, or who did it. Because obviously, it’s my fault. In fact, if the Enzo Mari X IKEA autoprogettazione table survived a day in our house, it’s only because our family and regular visitors were living in fear, subjected to a constant, low-level psy ops campaign of tense looks and warnings, with suspected leaners getting regularly guided toward the table’s side seats and away from the cantilevered ends.

Because the top clearly broke on Ikea’s butt joint, and not my own is of little comfort; it broke where the fulcrum was–the base. I knew it would/could happen when I decided to make my table top from horizontally built up Ivar shelving instead of the other two options I had: 1) tracking down the original, 200cm long Ivar shelves that had just been discontinued when construction began, or 2) using the thick, pine slab head and footboards from a king-size Mandal bed. The former, I nixed because I decided that building a table from discontinued Ikea parts might hinder the vast revolution in autoprogettazione-inspired Ikea hacking that would surely follow the debut of my project. The latter, well, the bed frame came already finished, and that felt a little like cheating.

Now, of course, with a card-table sized dining table, I’m more than ready to compromise. But Ivar long shelves are still discontinued, and now, it turns out, so is the wood-intensive Mandal bed, which has been redesigned to use no headboard, or a weird, slatty thing you mount on the wall.

That means I’m going to need to re-create the table top as-is, and reinforce it underneath, and hope that it holds. Or I’ll replace it entirely, probably with some slabs of sick, slick, ultra-deluxe 500-year-old sinker pine from the bottom of some icy river somewhere. Either way, I’ll be back in the basement, varnishing something soon.

Previously: The making of an Ikea X Enzo Mari table, in many chapters

The Good Wife

You know, I tried. I really tried, but there just are not enough hours in the day. You can all take down David Colman’s John Currin & Rachel Feinstein Style section article yourselves. Lord knows everything but the headline–“Their Own Best Creations,” which at least gives a nod to the existence of artifice, spin, image management, the subjective construction of the self–is ripe for the kicking.

I will say that it’s the conveniently swattable straw men that bugged me the most. The specious [or is it?!] notion that “the art world” somehow punishes those artists who aspire to–or even approach–their collectors’ lifestyles. When, in fact, “the art world,” such as it is, is all but obsessed with art’s wave/particle-like duality, its near-magical power to transform culture into capital and vice versa.

The art world has been laboring mightily for decades to accommodate and cater to the needs, desires, lifestyles, and politics of wealth-flaunters, hyper-capitalists, and consumptionists of all kinds, and it pisses me off to see all that hard work go unrecognized by the Style section, of all sections!

The idea that Currin and Feinstein’s conservative political views somehow transgress anything but the feeblest cliche of liberal “art world” orthodoxies. I guess it’s the notion of “an” “art world” that’s so easily thwarted by John & Rachel’s unabashed fabulousness that really gets me.

Such an art world is a fairy tale. There are also more art worlds, and a far greater range of political views within them, than the Style section cares to acknowledge. I can think of a dozen conservatives–even some card-carrying neo-cons–who are prominent, active participants in New York City’s art scenes: artists, dealers, and curators, too, not just collectors or museum people. This heterogeneity is who “we” are, and to pretend otherwise, or to ignore these differences is willful or naive, or both.

Or maybe it’s that political differences in “the art world” have long been tolerated, negotiated, or if need be, consciously set aside or even suppressed in the interests of achieving an art-related goal. And really, are there any political chasms that can’t be bridged by Blanchette Rockefeller’s noble response to questions of whether his years as an enthusiastic Fascist activist might preclude Philip Johnson’s election as a MoMA trustee: “Every young man,” she reportedly said, “should be allowed to make one very large mistake.” I’m sure it works, try it at home!

As for Rachel’s work, and her career, and the inevitable comparison to her husband’s, how can it not be eclipsed? Is it apparently impossible to say that? But what is Rachel to do? Not show? Not make? Show under a pseudonym? Is it impossible to wonder if Rachel’s career differs from John’s because of her medium? Or her content? Or her concept? Or her gender? Was it “being that glamorous” that caused Feinstein to “take [her] eye off the ball” over the last few years, Jerry? Might having and raising three kids play a part? Maybe what Rachel’s career is really missing is a good wife.

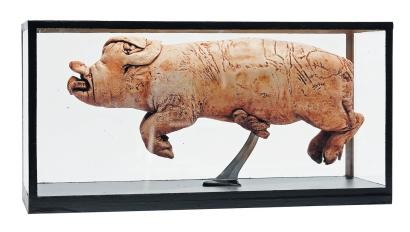

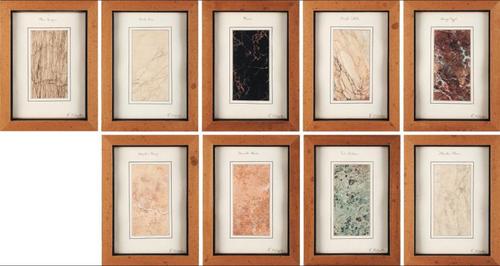

Animal, Vegetable or Minimalism?

Have we considered Damien Hirst’s vitrine sculptures from the Wunderkammer perspective? Because the giant grab-bag auction at Pierre Berge & Associes in Brussels is stuffed [heh] with disturbing taxidermy, eerie medical/scientific specimens, and elaborate butterfly displays. Yes, that is a butterfly skull under glass. If you’re playing any Hirstian drinking games, you are now passed out on the floor.

Or have we considered Olafur Eliasson’s art to be inhabiting a similar historical aesthetic trajectory?

Because seriously, put something in a bell jar, or on a tiny little display stand, and it gets immediately objectified and pretty damn near artified.

If not, then hop to it, Art History. Because right now, I’m too busy planning my show of found conceptualism and ur-Post-Minimalism:

Lot 451: a suite of 9 framed marble samples [est. EUR1300-1500]

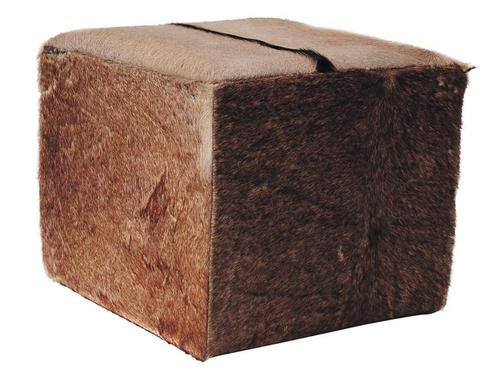

Lot 562: a cube-shaped Oryx-skin pouf [est. EUR 300-450]

I guess it’s really a pair: Lot 563: a cube-shaped boar-hide pouf [est. 300-450]

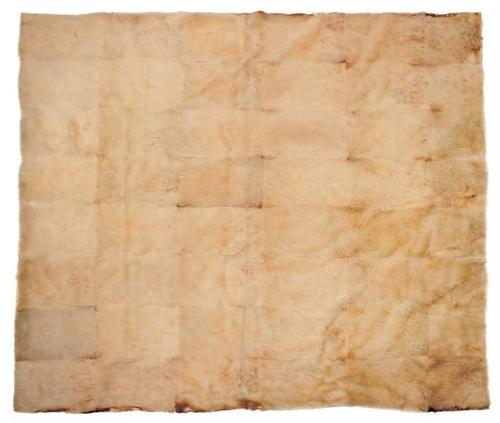

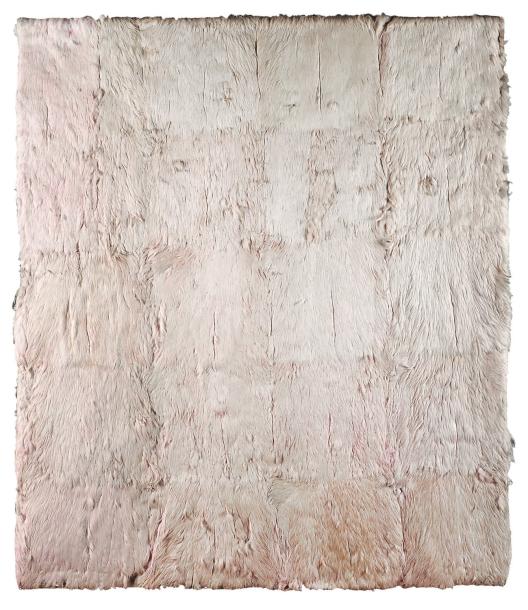

Lot 561: a large monochrome grid made of white wolf skin [est. EUR3000-5000]

I guess it’s really a diptych: Lot 823: a large monochrome grid made of pink flamingo feathers [est. EUR 1500-2000]

And a couple for the back room:

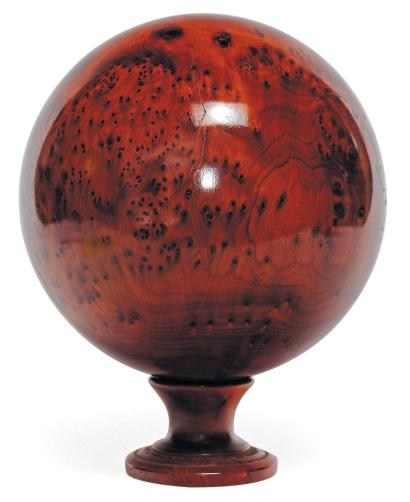

This could be bigger: Lot 504: a sphere [23cm dia.] of polished thuya root burl [est. EUR 150-200]

And this could be a bit less Madison Avenue, but still: Lot 576: a plaque of caravan salt from Mali [est. EUR 1200-1500] [ref. flickr]

The Second Meeting With The First Meeting Of The Erik Satie Society

I totally remember seeing John Cage’s The First Meeting of the Erik Satie Society in the summer of 1994. An unbound version was on view at the Fuller Building on 57th Street. Susan Sheehan Gallery. It was on during Cage’s phenomenal retrospective/exhibition/performance, Rolywholyover: A Circus, at the Guggenheim SoHo. [I followed that show around the country like a Phish head, from MoCA, to the Menil, the Guggenheim, to the Philadelphia Museum. The PMA show coincided with my graduation from business school, and I had a couple of weeks where I was able to go every day, and watch the museum’s art handlers perform their I Ching-generated list of reinstallations. A formative experience, one of the absolutely greatest museum exhibitions ever, and probably the greatest catalogue I own. Reproductions of works, poems, and texts are packed loosely in a mirrored aluminum box. It’s a good segue to the Satie Society, and ‘m going to go pull it out right after I post this.]

Anyway. The Merce Cunningham Dance Company just sold a copy of The First Meeting of the Erik Satie Society at Christie’s last week, and I’m a little surprised at how vague the description is. Apparently, Cage’s box set of artist books, drawings and prints was supposed to be an edition of 18, or 9, but then the edition of 9 is described as unrealized, plus an “unbound” edition of 6… Sounds a bit of a mess.

The gist of the piece is that in 1992 Cage invited artists to a birthday party for the French composer who influenced him so profoundly, and the gifts are the artworks, which Cage combined with his own Satie-themed mesostic/acrostics based on writings he admired, too. It’s basically an exercise of homage, inspiration, collaboration, and transformation. Folks like Johns, Rauschenberg, Sol Lewitt and Robert Ryman contributed works, and Cage used texts from the likes of Joyce, Duchamp, Thoreau and McLuhan. The whole thing came in a steel-framed, broken-glass valise, a reference to Duchamp’s famously cracked Large Glass.

I’m going to guess that the version I saw was unbound, because the elements were mounted between freestanding glass panels around the gallery. So there’s one. How there could be ambiguity about work produced by this constellation of major artists just a few years ago–holy crap, almost 20 years ago–is a mystery to me.

Sale 2441, Lot 177: The First Meeting of the Erik Satie Society, by John Cage, est. $90-120,000, sold for $116,000 [christies.com]

Holy crap, $500? Rolywholyover: A Circus on Amazon [amazon]

Previously: Richter’s 4900 Colours and Cage’s Rolywholyover via sippey

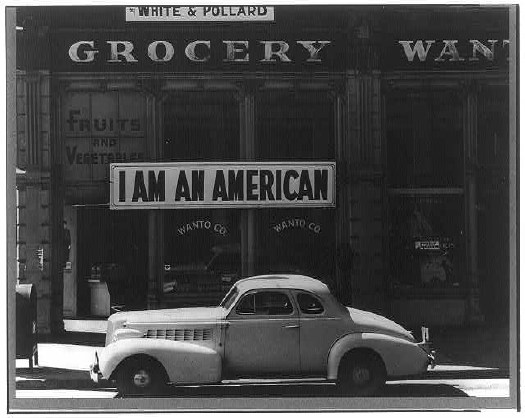

I Am An American

I’ve written and been inspired by Ansel Adams’ WWII Japanese-American internment camp photos for years, but inexplicably, I haven’t looked closely at Dorothea Lange’s. Paul has some intriguing examples at Eyeteeth. He also notes that Lange was actually covering the internment process for the War Relocation Authority, which quickly became as complicated as you might imagine. According to the Library of Congress, the US government immediately censored many of Lange’s photos, which tended to highlight the patriotism of the Americans being imprisoned without cause or charge. They weren’t widely seen or known until 1972, when the Whitney organized an exhibition about the internment titled Executive Order 9066.

The caption on this photo, taken in San Francisco in March 1942, when the store was being confiscated and its owner jailed, says the UC graduate nisei had installed the banner outside on Dec. 8, 1941. So on the bright side, in those four heated, panicked months, no one tore it down.

Day of Remembrance – Dorothea Lange’s Japanese Internment Photos [eyeteeth]

Dorothea Lange: Women Come To The Front [loc.gov]

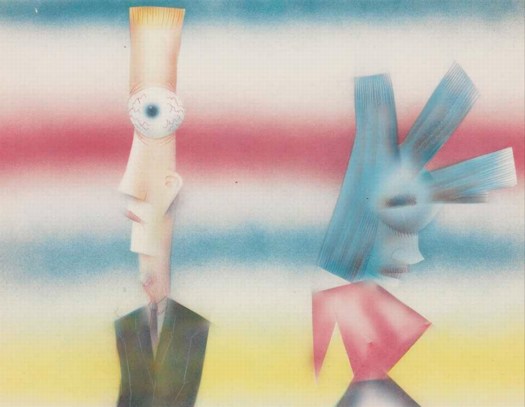

Mormon Missionary And Companion, For Sale, By Jim Shaw

I don’t know how this slipped by me, but now it’s going up for sale tomorrow at Christie’s: a very early Jim Shaw pencil & airbrush drawing from 1981 with the obvious-now-that-you-mention-it title, Mormon Missionary and Prostitute Making Each Other Feel Guilty.

In 1981, Shaw wasn’t even really showing his art yet–the earliest group show in his current, abridged bio wasn’t until 1986. And he was years away from the unveiling of O-ism, his homebrewed, Life of Brian-style, parallel universe version of Mormonism, which he showed at the Swiss Institute and Metro Pictures in 2002. [O, and there was The Donner Party his awesome O-ist reimagining of Judy Chicago’s feminist masterpiece, The Dinner Party, which was at PS1 in 2007.]

Anyway, Shaw was still busy in 1981; Ed Ruscha helped him publish Life And Death, an artist book compilation of airbrush drawings that do look a bit like this Mormon Missionary here. Perhaps they are related.

Lot 30: Jim Shaw, Mormon Missionary and Prostitute Making Each Other Feel Guilty, est. $3000-5000 [christies.com]

From The Mixed Up Files Of Basically Everyone

What’s that, dear? Oh, nothing, just some legendary but unknown drafts for the first film adaptation of Ian Fleming’s Casino Royale, by veteran Hollywood screenwriter Benjamin Hecht.

After reading various references to the early 60s script, Jeremy Duns decided to go looking for it, and whaddyaknow, there it was, sitting in Hecht’s archive, which is at the Newberry Library in Chicago. Apparently, in the intervening decades, no one had ever bothered to actually look for it:

[T]hese drafts are a master-class in thriller-writing, from the man who arguably perfected the form with Notorious. Hecht made vice central to the plot, with Le Chiffre actively controlling a network of brothels and beautiful women who he is using to blackmail powerful people around the world. Just as the theme of Fleming’s Goldfinger is avarice and power, the theme of Hecht’s Casino Royale is sex and sin. It’s an idea that seems obvious in hindsight, and Hecht used it both to raise the stakes of Fleming’s plot and to deepen the story’s emotional resonance.

It’s exactly the kind of mind-boggling, serendipitous archive find that keeps me going on this Johns Flag hunt, even when the more skeptical part of me is saying, “Seriously, how could Jasper Johns’ first flag painting have been stolen, and missing, and then resurface in his own dealer’s office, and then disappear again, and no one knows where it is or even what actually happened to it?” But the more I dig and ask around, the more I find that, though plenty of people gossiped or speculated, almost no one has ever actually searched for it.

UPDATE/CLARIFICATION/APOLOGY/&C. Ha, ha, I guess if I think about it, yeah, my meant-to-be-exciting-thrill-of-discovery-in-uncharted-archives anecdote below could make actual archive professionals cringe. And I guess I didn’t think of that. OR mean it as any kind of criticism of the way the AAA works, just the opposite, in fact.

Fortunately, Barbara Aikens, the Chief of Collections Processing at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art took the time to correct some inaccuracies and clarify some of the wrong implications in my account. Which, I didn’t really– I mean, it was really meant to be kind of an amusing offhand story, not a transcript, which– Anyway. My bad.

A few trips ago, while researching at the Archives of American Art, I opened a white cardboard box, indistinguishable from all the others on the outside. But instead of the neatly labeled, acid-free folders, I faced a mishmash of giant envelopes, ragged edges, and old, manila folders. And a rubber banded brick of old AmEx bills. And some matchbooks. What a mess. It was more time capsule than archive.

In the middle of a sheaf of clippings and tear sheets, interviews and reviews and feature articles about Robert Rauschenberg, I came across an odd little card. No, it’s a transparency showing an Apollo alnding capsule. No, there’s three. Blue, magenta, cyan, waitaminnit, this is taped together by hand. It’s an object, maybe even a work, made of layered transparent sheets, similar to Rauschenberg’s editions made from multiple sheets of plexiglass. Shades (1964) is one; I have a similar set of plexi discs somewhere from 1970-1, in a boxed set of multiples titled, Artists and Photographs. Here you go: Revolver.

The other day, i recognized that space capsule image as the one in the Hirshhorn’s big Rauschenberg screen/painting, Whale, which is also from 1964. Maybe Bob sent that little objet home after a studio visit or something. But should it really be in here, in the archives, hanging out with greasy-fingered riff-raff like me? Maybe I should say something.

A couple of folders later, I carefully extract a large, tattered, manila envelope with something about a group show or benefit scribbled on the outside. The first thing I pull out is a signed Jim Dine drawing. Then another. The next one is an Oldenburg. I pull out a piece of black paper, which turns out to be a chalk drawing. A little dust gets on my hands. At which point–I mean, fingerprints, right? I’m totally busted–I call the attendant over with a hearty, “Uh, did you know there’s a bunch of original art in here?”

No, she did not, but yes, that happens, because, in fact, budget, priorities, low demand, &c., &c, some of this collection’s boxes had not been processed yet. I was probably the first person to even look through this box since it had come in over 25 years earlier. She gave me a stack of acid-free paper to slip in between the various drawings, and I decided that, though it looked like a blast, the stuff in the packet was obviously not related to my research–at the very least, if Johns’ Flag had been stuffed inside, I would’ve seen it–so I put it all carefully away.

I guess I’m just saying, there’s stuff out there. And no one’s been looking for it, so get cracking.

UPDATE I thought I was being helpful by not identifying the collection I was using here, but of course, Barbara knew right away what it was: the Alan Solomon Archives. The Solomon material had come into the AAA in waves, and the unprocessed box had actually entered the Archive in 2007, not, as I misunderstood, 25+years ago.

The presence of art, drawings, sketches, etc., while not a collecting goal of the Archive, is also not unheard of, and such material typically remains in accessible within the collection, where it is to be handled with care.

Barbara points out that while I made it sound like there I worked through a stack of acid-free paper, in fact, I only inserted three sheets between a couple of drawings. This is true. I was given a stack, but after replacing the works I’d taken out, I figured I’d leave the rest of the handling to the professionals, and so I closed up the box.

On the point of processing, I can’t do better than Barbara’s statement:

On average, we process and preserve about 500-700 linear feet per year; this includes writing full and detailed electronic finding aids that are available on our website. In addition, we are the only archival repository in this country that has a successful ongoing digitization initiative to digitize entire archival collections, rather than just selected highlights from collections. To date, we have digitized well over 100 collections, totaling nearly 1.000 linear feet and resulting in 1.5 million digital files. Archival repositories from across the country regularly consult with us on our large scale digitization methodologies, work flows, and infrastructure.

I would hate to think that users will think less of our major efforts here at AAA to increase access to our rich resources, or, worse, think that we do not care about the stewardship of collections. It is one of our ongoing mission goals and we devote considerable staff resources to our processing work. However, the work is never done to be sure.

And thank you for it. And for the clarifications. Carry on.

Casino Royale: discovering the lost script [telegraph.co.uk via daringfireball]

Live From The Gramery Hotel

Warm nostalgia apparently equals d-bag public access video + time.

Reading Andrew’s report from the Dependent Art Fair, I kept flashing back to the Gramercy, and all the art in the bathrooms, and on the beds, and the insanely crowded hallways.

And whaddya know, there’s a link to a 1995 Gallery Beat episode from “the Gramery Hotel,” where those asshats wandered in on work by unknown artists like Mark Dion, and Tracy Emin, who was not quite protected by the utterly baffled Jay Jopling.

I’d totally forgotten how much I hated that show. And now I’ll probably end up watching the entire archive.

Classic Gallery Beat TV [gallerybeat.net via 16miles.com]