In anticipation of Creative Time Summit II–it’s October 9-10, just a few weeks away!–I’ve been watching some of the talks from last fall’s Summit, organized by Nato Thompson held at the NY Public Library. [For an overview, check out Frieze’s write-up of the quick-fire speechifying marathon.] Like the Oscars, speeches are cut off right on time by pleasant music. It can be kind of harsh [sorry, Thomas Hirschhorn and guy from Chicago’s Temporary Services making his big, final pitch for help] but rules are rules.

So far, I’ve found the longer [20m vs 7m] keynote speeches to be the most fascinating. From the super-low viewer numbers to date, the fan club is pretty small. Anyway, watch these and pass them around:

Teddy Cruz, the Tijuana/San Diego architectural investigation guy has the single most intense 6:30 min talk I think I’ve ever seen. Almost makes up for not being able to see his slides.

Art historian Morris Dickstein’s keynote about Evans, Steinbeck, Astaire, and art of the Depression was interesting and timely, easily the most wrongly underappreciated, too:

Okwui Enwezor’s talk was smart and incisive, unsurprisingly, and made me wish he’d talked longer–and about more than a single documentary photo used by Alfredo Jaar.

But by far the best, the most moving, the one that got my head nodding and made me want to write things down for later, was Sharon Hayes’ reminiscence of moving to New York in 1991, smack into the middle of a teeming downtown art/activist community dealing with the AIDS crisis. It was gripping, and made me remember how important, vital, art can be, not for the the objects it generates, but for the effect it has on people, singularly and together, at a moment and in a place.

Creative Time New York YouTube Channel [youtube]

Author: greg

Westinghouse World’s Fair Pavilion, Or Eliot Noyes’s Huge Shiny Balls

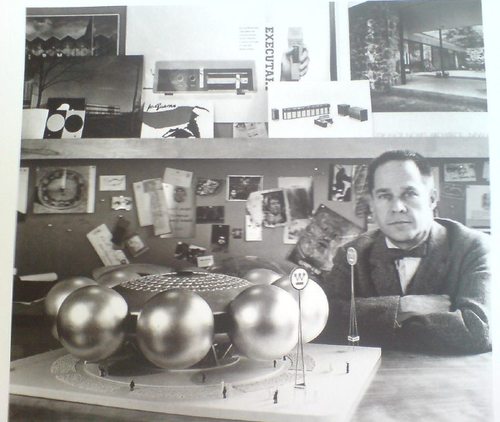

I love Eliot Noyes as much for his own designs as for his role as catalyst, instigator and patron for some of the greatest modernist objects and buildings of the postwar era.

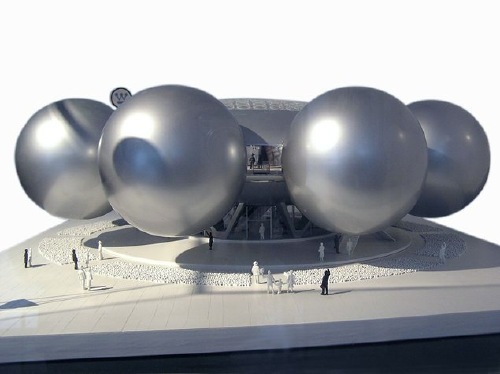

And yet somehow I hadn’t made the connection to his unrealized design for the Westinghouse Pavilion at the 1964 New York World’s Fair, which consisted of eight 45-foot diameter silver spheres floating off of a central domed foyer. Giant silver spheres in 1961? Wherever would the idea for such a form come from?

Thanks to dealer-turned-design curator Henry Urbach, SFMOMA acquired the Westinghouse maquette in 2006, but the museum’s description doesn’t make any reference to Project Echo or any design references at all.

Next, I turned to Phaidon’s sleek-yet-frustrating Eliot Noyes monograph, written by Noyes’s longtime collaborator Gordon Bruce. Though it’s chock-full of info and photos [including the one above, of Noyes posing with his maquette], it turns out to be more bio snapshot than design history. There’s a little about the bureaucratic wrangling that nixed the pavilion [and replaced it with a second company time capsule, to match the 1939 one], but nothing about the design.

Oddly, there’s no mention at all of the scaled-down pavilion which was eventually built [image via], even though it has the maquette’s signage, and it looks awfully similar to the round gas station canopies Noyes would design for Mobil a couple of years later. [image via agilitynut.com’s great collection of gas station design photos]

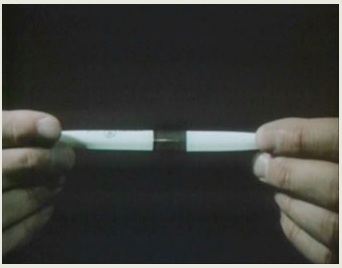

update: indeed, Noyes & Assoc. are credited in the World’s Fair Time Capsule Pavilion Brochure, which turns out to be the uncredited source for Wikipedia’s image. That’s the torpedo-shaped time capsule right there, btw, suspended 50-ft above the ground by the three masts.

Eliot Noyes, Westinghouse Pavilion, 1961 [sfmoma.org]

Oh No, There’s A Deutschen Bundespost Type TelH78 Telephone Booth On eBay

I’ve been trying for months to figure out the designer of what I think is one of the slickest phone booths around, the Deutschen Bundespost Typ TelH78 Telefonzelle.

I’ve been trying for months to figure out the designer of what I think is one of the slickest phone booths around, the Deutschen Bundespost Typ TelH78 Telefonzelle.

You know it when you see it. It’s bright yellow, a fiberglass and safety glass box with beautiful rounded corners. It has just the stability, utilitarianism, officialism, and future-forward design you’d expect from a European, state-run telecommunications monopoly in 1980, which is when I think they started deploying them. [Near as I can tell, the type number refers to the year it was designed.] It’s the Helvetica of phone booths.

And it’s disappearing, if not completely gone. I haven’t roamed the German byways to see how far T-Mobile’s awful magenta & glass booths have taken over, but these days, phone booths themselves seem barely more than excuses for street advertisements. A few Telefonzellen, including TelH78s–oh, wow, look at that olive drab one–are being converted into tiny, neighborhood lending libraries.

And now one’s on eBay.de. In beautiful condition, a mere EUR71. For local pickup in Fritzlar, just outside of Kassel. Weighs around 100kg. So beautiful, so tempting.

Telefonzelle der Deutschen Bundespost, ends Aug. 19 [ebay.de]

Telefonzelle (Deutschland) [wikipedia]

أنا ♥ نيويورك

John Emerson saw an “I [HEART] NY” flyer in Arabic posted in the East Village a few days after September 11, 2001. He posted a large, printable graphic version on his blog a year later.

A few months after that, I noted that Maurizio Cattelan had created a

t-shirt in an edition of 100, which was sold via Printed Matter. The Printed Matter folks now have no idea what the story was, and I’m waiting to hear back from Maurizio, but I think it’s way past time for another edition.

The Raum der Gegenwart, Then And Now

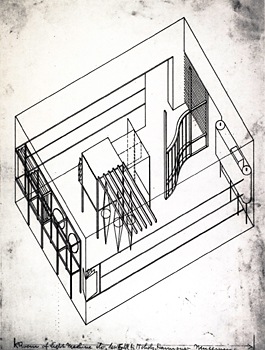

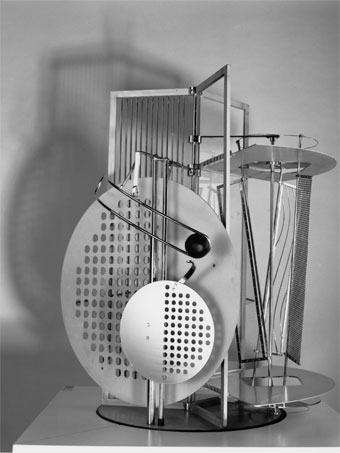

In addition to being the subject of his film and photographic work, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator modulated light and space as a sculptural installation, and it served as a Light Prop for an Electric Stage. But in 1930, the artist had also planned on installing it at the Hannover Provincial Museum.

In addition to being the subject of his film and photographic work, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator modulated light and space as a sculptural installation, and it served as a Light Prop for an Electric Stage. But in 1930, the artist had also planned on installing it at the Hannover Provincial Museum.

Alexander Dorner, the director of the Landesmuseum, had invited Moholy-Nagy to design the final room in the chronological reinstallation of the museum’s collection, the Raum der Gegenwart, The Room of the Present Day. The room was to have interactive exhibition elements devoted to film, architecture, and design. And at its center: the definitive art work of Moholy-Nagy’s future, the Light Space Modulator, performing inside its light-lined cabinet. Was to have, because Moholy Nagy’s plans were never realized in Hannover.

Frankly, it sounds more like the Room of the Multimedia Future. In the press release for Licht Kunst Spiele, an exhibition of Light and the Bauhaus last year at the Kunsthalle Erfurt, the Room of the Present Day was said to have anticipated “an art which does completely without the hand-painted, auratic picture.” [Anticipated is right; Walter Benjamin didn’t write “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” until 1935. I guess aura was in the air.]

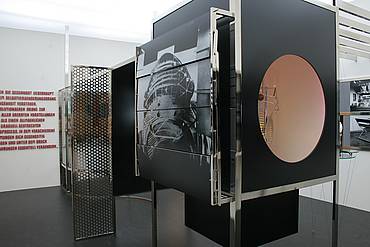

And speaking of reproduction, the curators for that show, Drs. Kai Uwe Hemken and Ulrike Gärtner teamed up with designer Jakob Gebert to finally realize Raum der Gegenwart according to Moholy-Nagy’s designs and intentions. From the photos, the Raum looks like a life-size Light Space Modulator, the Light Prop transfigured into a Light Stage. Or Light Theatre.

The Raum traveled to Frankfurt for the Schirn Kunsthalle’s Moholy-Nagy retrospective, and it has now settled into the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, where it is part of Museum Modules, a show about, I guess, famous museum exhibition re-enactments. [images via crossroads mag and vanabbemuseum.nl]

Whether that is the Van Abbemuseum’s 1970 Light Space Modulator in there, or yet another replica, I don’t know, but I’ll assume it’s the former. Perhaps the answer lies in “The Raum der Gegenwart (Re)constructed,” a thorough and fascinating-sounding article by Columbia’s Noam M. Elcott, which was recently published in the Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians.

update: Yes and no. Elcott’s article is fascinating, though, and he praises the “historical acumen and curatorial courage” of putting the Light Prop in the lighted box it was arguably conceived for. He goes further, arguing persuasively that Light Prop, as an embodiment and producer of cinematic abstraction, is the conceptual center of the Raum der Gegenwart. Very interesting stuff.

So Many Light Space Modulators

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Licht Raum Modulator, 1970 reconstruction, image: bauhaus.de

Did I say a few minutes?

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy spent around eight years [from 1922-30] building his Light Space Modulator, and then he carted it around Europe, and to America, reworking it and repairing it until his death in 1946. His widow Sybil donated it to the Busch-Reisinger Museum at Harvard in 1956.

Anyway, while the kinetic and light art movements it prefigured were kicking into high gear, the original LSM was in quite a state of disrepair. It sounds far, far away from Moholy Nagy’s own early description of it, which included not only the motorized glass, cellophane, aluminum, and steel construction we know, but a stage-like box lined with synchronized, colored lights. [I was going to quote some of the description from Medienkunstnetz, but it doesn’t clear anything up; just read the whole thing.]

Yet Moholy-Nagy’s posthumous influence was growing, and the LSM was exhibited widely throughout the 1960s in its second[ary] mode as a room-filling projection. After some malfunctions and damage during a big KunstLichtKunst exhibition at the VanAbbemuseum in Eindhoven, though, something had to be done.

In 1969-70, the Harvard art historian-in-training Nan Piene was studying Moholy-Nagy’s work and wanted to include the Light Space Modulator in an exhibition at Howard Wise Gallery in New York. [Nan’s then-husband, Otto Piene, also showed kinetic and light works at Howard Wise. He was a fellow at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, which he took over in 1974.]

So with Mrs. Moholy-Nagy’s permission, Mrs. Piene had the LSM refabricated. Twice. One copy went on view at Howard Wise in 1970. One went to the Venice Biennale. One was flagged for the Bauhaus Archiv in Darmstadt, and the other ended up back at the Van Abbemuseum.

In his NYT review of the show, Hilton Kramer wrote at length about the implications of this “entirely new kind of art object–costly and painstakingly made facsimile reproductions of certain classic works of modern art.” Moholy-Nagy’s intent, according to Piene according to Kramer, was the Constructivist fusion of object and space, light and motion, perception and experience. But.

As usual with Moholy, what we have here is not a completely successful work of art but a brilliant statement about a new possibility for art. In an age of conceptual art, when ideas need only be stated to be taken for realizations, the distinction I am making may seem a little archaic. But for those of us who remain firm in our belief that what is important in art is not what the artist says he is doing or intends to do or is said to have done, but what he actually achieves in the work itself, the distinction is crucial.

Just as I didn’t research the Eames Solar Do-Nothing Machine with the intention of tracking the history of Moholy-Nagy, I didn’t dig into the refabrication of the LSM with the intention of agreeing with Hilton Kramer about conceptual art. But here we are. With his Telephone Pictures, Moholy-Nagy was famously ahead of the curve on outsourced production, so it might be natural to see his work as fitting easily with the era’s emerging conceptualist norms.

Here’s a video of the Eindhoven Light Space Modulator in action:

I have to say, it’s fantastical and beautiful, but it’s also precious and underwhelming. Like Kramer, I am glad it exists, but I don’t quite know what to think of it. Maybe that it works best as film and photo, i.e., as a prop, shot, cropped and edited by Moholy-Nagy’s own eye.

In 2006, Tate Modern and the Busch Reisinger arranged with the Moholy-Nagy estate, now controlled by the artist’s daughter Hattula, to make yet another, yet more definitive replica of the Light Space Modulator, which by now is going by an earlier, more correct title, Light Prop for an Electric Stage. After the Tate showed it, Peter Nesbit, the [Daimler Benz] Curator at the Busch-Reisinger showed their new, functioning replica alongside the static original in Light Display Machines: Two Works by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy.” Except that one condition of the replica authorization agreement was that the 2006 version, at least, “not be considered a work of art.”

That is the word according to a paper/discussion presented at Tate in October 2007 by Henry Lie, the director of the Harvard Art Museums’ Straus Center for Conservation Studies. [Lie discussed the details of the history of the LSM LPfaES at a workshop titled, “Inherent Vice: The Replica and its Implications in Modern Sculpture,” which is just about the most awesome collection of art reading material this side of the Packing, Art Handling & Crating Information Network.]

The 2006 replica was made by a German engineer named Juergen Steger, and Lie’s presentation goes into exquisite detail on his build. Steger referenced not only the original and all the photo and film evidence, but also the 1970 replicas, which were built, I should have mentioned, by Woodie Flowers, an MIT graduate student who went on to become a rather legendary robotics professor at the school.

When I first stumbled across this whole Light Space Modulator replication business a couple of months ago, I decided to email Prof. Flowers to see what was up. He called me right back, and we had a quick, intense, funny, and fascinating chat about the project, how he got involved, and how it went down. I will go into more details of Woodie’s account in…in a few minutes.

Light Space Modulator, Remade

I’d known Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s 1930 kinetic sculpture Light Space Modulator indirectly as a film subject, and then in 2002 through incredible color photographs Oliver Renaud-Clement showed at Andrea Rosen in 2002. [And again, in direct relation to the artist’s sculptures in 2007.]

I’d known Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s 1930 kinetic sculpture Light Space Modulator indirectly as a film subject, and then in 2002 through incredible color photographs Oliver Renaud-Clement showed at Andrea Rosen in 2002. [And again, in direct relation to the artist’s sculptures in 2007.]

The press release for that show quotes Moholy-Nagy on the LSM:

…a structure that is made to develop the sense of space and explore the effective relationships which must be within the quality range of any architecture – an ABC of architectural and projective space…

The mobile was so startling in its coordinated motions and space articulations of light and shadow sequences that I almost believed in magic.

Which is nice.

But I came to know it not as an object itself, a sculpture, and not as a film prop [the original title for the work is Light Prop for an Electric Stage], when I began researching the replication a similar object, Ray and Charles Eames’ Solar Do-Nothing Machine.

Eames called their creation, built in 1958 for an Alcoa ad campaign, a “toy,” not a work of fine art. My own interest was to use the context of art to recreate the Do Nothing Machine–I want one and want to see and experience it in person. But it quickly became apparent to me that the Eameses’ modernist, experimentalist work already resonated with the contemporaneous history of light and kinetic sculpture. Which Moholy-Nagy’s work both prefigured and directly influenced.

Filled with dazzling close-ups of whirring, colorful components, the Eameses’ film of the Solar Do-Nothing Machine could be a Technicolor Hollywood remake of Moholy-Nagy’s film, Lichtspiel. But the Light Space Modulator turns out to be directly related to this project in another not insignificant way: it’s actually a replica.

Moholy-Nagy worked on the LSM for an easy decade until 1930, but he also tweaked, repaired and altered it for use and exhibition up until his death in 1946. His widow Sibyl Moholy-Nagy gave the work to Harvard’s Busch-Reisinger Museum in 1956.

But that was not what was exhibited when light and kinetic was the new hotness in 1970, both at the Howard Wise Gallery in New York, and at the Venice Biennale. And it’s not what is exhibited now or since, or what is shown in nearly every image of the Light Space Modulator published these days. Those are all refabrications, or replicas, or approximations, really, of the original–or at least of its final state.

So from Eames, I’ve been diverted by the fascinating history and reincarnations of the LSM. Which I’ll get into in a minute.

Heinz Mack, Daddy

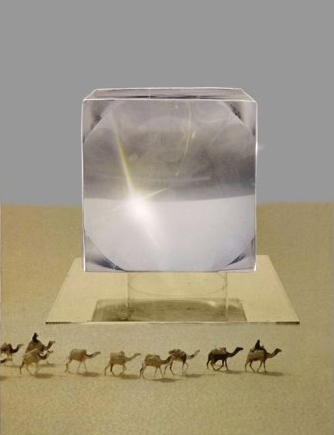

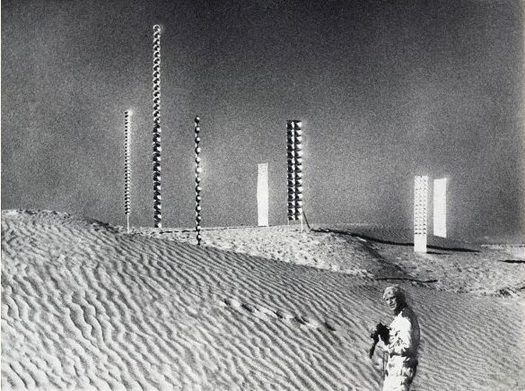

Digging around on Moholy-Nagy’s Light Space Modulator and its relation to a later generation of kinetic light works by artists like Otto Piene, I came across some early works by Piene’s Zero Group co-founder, Heinz Mack.

As early as 1960, Mack was showing plans for his Sahara Project [above, image via mack-kunst], which would, in classic Zero style, embody the most reductivist expression of art’s essential elements, light and space.

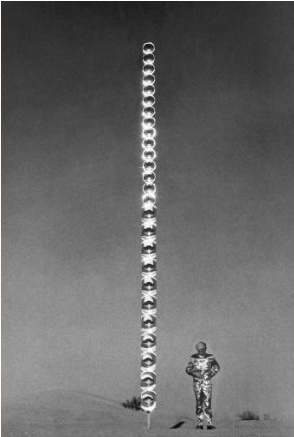

Mack showed his reflective and/or lit Lichtstele sculptures at various places, including in 1966 at Howard Wise Gallery, a center of kinetic and self-consciously future-oriented art. It took until the late 60’s for Mack to realize his utopic, minimalistic, phenomenological sculptures in the desert, though.

They look utterly fantastic in photographs. Or film stills. Mack produced a documentary of his art projects in Tunisia in 1968-9 with the German television network ARD humbly titled, Tele Mack, Tele-Mack, Telemack.

I need to read further to figure out how Mack’s work relates to what was going on around it. [The artist himself seems to see himself as a prophet of the future, a German incarnation of the otherworldly artist-showman in the Klein & Dali type. For some reason, this awesome still from Tele-Mack of Mack in his space suit makes me think of Klaus Kinski.]

In his own bio, Mack namechecks artists he met in New York such as Reinhardt, Newman, and Marisol. But Tele-Mack, and by extension, his whole Sahara Project, have an inexorable connection to Land Art, too, and Smithson’s Displacements. Tele-Mack was produced with the artist couple Gerry Schum and Ursula Wevers, who founded The TV Gallery in 1967. From Ute Meta Bauer’s chronology of artist-driven exhibitions:

[The TV Gallery and later, the Video Gallery] exhibition took place on TV. Its duration was the length of the program.

Over a period of six months, Schum shot films with Land Art artists. He wanted to dematerialise art – to take away the character of art as a consumer item (opposition to Pop art).

Bernhard Höke, Hannah Weitemeyer and Gerry Schum made the film Konsumkunst – Kunstkonsum (1967). In this film, artist Heinz Mack stated that his art will exist on television and will only be shown to the audience by this medium, only to be destroyed afterwards. Later, in May 1969, this was realized in the Telemack TV broadcast.

Otto Piene also made an exhibition only for TV – a multimedia show.

Let’s file that last one away, about a Piene TV show, for later.

If Mack’s work was intended to disappear after being photographed or filmed or aired, it’s working. I can’t find a hint of Tele-Mack anywhere online, though it is apparently in various film archives. Mack has worked steadily, producing large, permanent works for public, government, and corporate situations. But his earlier work exists largely in the same handful of documentation photos. He installed a large Lichtstele in front of the Art Museum that was the center of the Osaka Expo70, but I can’t find a picture, and the only Japan photo on Mack’s website is the artist surrounded by young women in kimonos.

Perhaps the catalogue for the Ludwig Museum’s 2009 show, Heinz Mack, Licht der Zero-Zeit, has something. According to the show’s writeup, most of the works in that show come from the artist’s collection and hadn’t been seen for decades.

As dazzling and pristine and sublime as the work appears, I’m not sure there’s still a there there. Maybe it’s enough for someone rebuilding society in a postwar atomic present. But now that it’s historical, I think The Art of The Future needs to be more than Not The Past.

Meanwhile, if anyone has any leads on how to see Tele-Mack, I’d love to hear it.

Someone Get Moving Serra Moving

Breaker, Breaker One-Nine,

I got Moving Serra, a documentary about transporting Richard Serra’s 242-ton sculpture Sequence cross-country, from MoMA to LACMA on a fleet of flatbeds, that’s blowing my mind right now.

We need a convoy of Serra torqued spiral/ellipse collectors to load their big rigs with completion funds right now and head on over to director Tom Christie’s place, over?

Moving Serra [movingserra.org]

The Gerhard Richter Website Reveals All. Almost All.

Oh Gerhard-Richter.com, why did I ever doubt you?

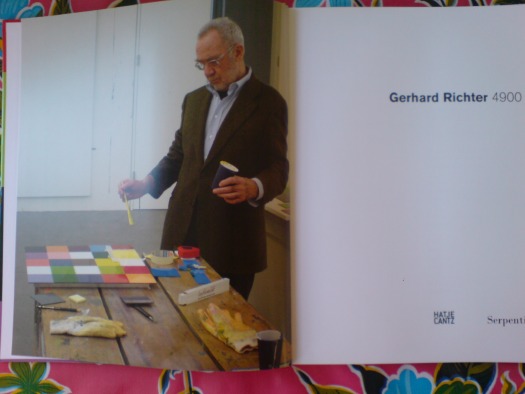

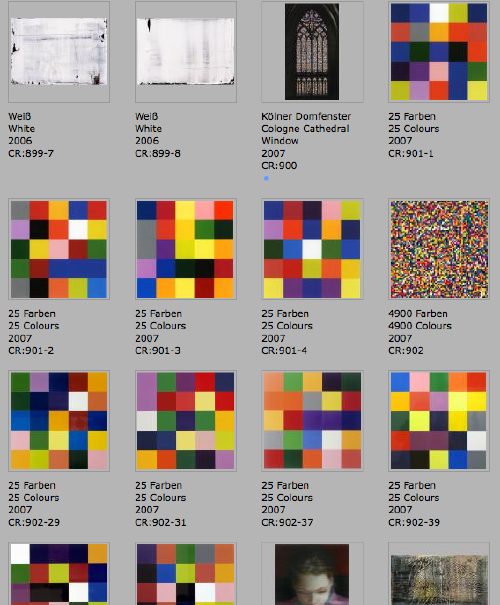

Last February, while holed up in the Snowpocalypse, I thought the hell out of the Serpentine Gallery’s catalogue for Richter’s 4900 Colours. The work consists of 25 enamel color squares arranged randomly on 196 5×5 aluminum laminate panels, and it relates very closely to the random, pixel-like stained glass window the artist created for the Cologne Cathedral in 2007, which was in turn related to an earlier color grid painting Richter did in the 1970s.

The frontispiece of the catalogue [above] shows the artist, nattily dressed, with brush and paint in hand, contemplating the final yellow square on a 25-square panel. Yet the text describes the actual production process for 4900 Colours, which involved random color placement determined by computer [the same program used to create the window], and mass production of enamel tiles, which were assembled and bonded to the aluminum substrate.

How to reconcile this apparent contradiction: Benjamin Buchloh praising the work’s industrial facture, while the making of photo captures The Touch of The Master’s Hand? And to complicate matters–or to solve the paradox–the grid on the painting Richter was photographed working on does not match any of the 196 panels in the piece.

The answer was right there on gerhard-richter.com all along. Almost. A search for all paintings made in 2006 and 2007, around the time of the cathedral window and 4900 Colours, turns up ten paintings, all 2007, titled 25 Colours, which have identical dimensions and materials, and which appear to have identical colors, as the 196 panels in 4900 Colours.

Thanks to the artist’s catalogue-raisonne-as-you-go numbering system, we can see the order in which they were created, and their apparent relationships or context. The Cologne Cathedral window is actually listed under paintings as CR:900, and is followed by four 25 Colours works, CR:901-1 through 901-4. Then comes 4900 Colours, CR:902, and six more 25 Colours numbered–wait for it–CR: 902-29, -31, -37, -39, -49, and -50. Which sounds like a series of four works, plus a series of panels, 196 of which go together, and 6 of which become autonomous works.

But. The photo Richter’s painting up top doesn’t match any of these ten, either. And if sharing a CR number means anything about their production, then the six 902 paintings are made exactly like 4900 Colours: at an auto body shop. Are CR:901’s handpainted? Is the photo in the book of a reject, or a study, a 900.5 whose handpainted facture didn’t pass muster? I guess we still don’t know.

This chronological view, though, adds another dimension to the context of Richter’s process, and it ties together three major projects involving randomness: 4900 Colours, the Cathedral window, and a suite of six large abstract paintings named for John Cage. There are 25 more squeegee paintings in between the window and the Cage paintings, but they are listed under only two CR numbers: 898 and 899. If I understand my Richter process, that means he worked on them in two batches, which might have taken “weeks.”

I’d completely forgotten that the installation video for 4900 Colours reminded me of Cage’s incredible exhibition-as-performance, Rolywholyover.

But I remembered watching Rob Storr talk about the Cage Paintings, though he doesn’t project their relationship forward. Or sideways. Richter’s window was dedicated in 2007, but the design was unveiled, fabrication had begun, and fundraising had been completed in September 2006. Which means Richter was working on the window and the Cage Paintings concurrently.

Storr quotes Cage on how, whatever randomness exists in your process, what’s not “an accident is what you decide to keep.” Which is about as close an answer as I can get for what happened to that grid painting up top.

So did the need for window randomness lead Richter to Cage, or did Cage lead Richter to randomness? I guess I’ll have to start digging.

Gerhard Richter 4900 Colours Microsite

In addition to the world’s greatest artist website, artist Gerhard Richter also makes paintings.

Now these two endeavors come together with the debut of a micro-site devoted to 4900 Colours, the set of 196 5×5 grids of 25 randomly applied enamel-painted squares, mounted on Aludibond panels. 4900 Colours can be exhibited in any of 11 configurations. Above is Version IX, which I chose for its apparent zooming-in-on-pixels quality.

One point of note: the website lists 4900 Colours in the /editions/ folder. Update: the microsite URL has changed; it is now listed in /paintings/

And two points of great relief: the 4900 individual squares were indeed sprayed-on enamel, not handpainted by the finely dressed artist; and there are no drop shadows. I think we are making real progress here.

www.gerhard-richter.com/art/paintings/4900-colours/ [gerhard-richter.com via @gerhardrichter]

Previous coverage of 4900 Colours:

The Making Of, with special guest star Benjamin Buchloh

About facture and that handpainted square

About drop shadows and diagrammatic abstraction

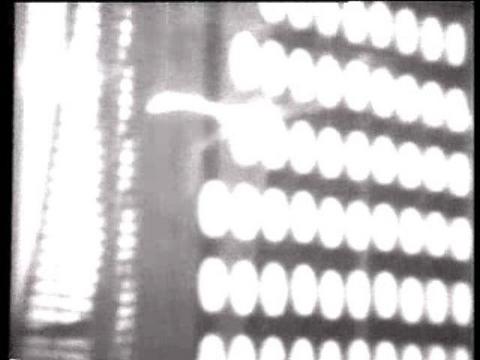

Lichtspiel/ Lightplay by Laslo Moholy-Nagy

That Google Street View snafu yesterday reminded me of a still from Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s 1932 abstract//constructivist short film, Lichtspiel, or Lightplay.

Normally, I’d say that’s the art-nerdiest possible free association in the world, but I’ve actually been meaning to write about Moholy-Nagy’s film for a while. Or more specifically, about his incredible kinetic assemblage/sculpture used to make Lichtspiel, the Light Space Modulator.

Light Space Modulator is a motorized sculpture made of glass, mirror, steel, and acrylic, and it was a crucial object–or project–for Moholy-Nagy for more than two decades. The dates generally given for its construction are 1922-30, but the artist worked on or with it until he died in 1946. Last fall, Alice Rawsthorn wrote in the Times about the tragicomic scene of the refugee artist fleeing the Nazis in the 1930s, family and Light Space Modulator in tow, and having to explain the sculpture to customs and border officials along the way. The original was given by Moholy-Nagy’s widow to the Harvard Museums, but more on that later.

According to the artist’s official chronology, Lichtspiel [full title: Lichtspiel schwarz weiss grau] was made around 1930 in Berlin, and first shown in 1932 [MoMA has a brochure, designed by the artist, for an exhibition and screening.]

According to MKZ:

Lichtspiel, schwarz-weiß-grau was originally supposed to consist of six parts, but only the last part was filmed. The first five parts were supposed to show different forms of light in set combinations: from the self-lighting match, automobile headlights, reflections, moonlight, and colored projections with prisms and mirrors to the production of the “light prop,” [i.e., the LSM]

This surviving segment/film, one of 7 extant Moholy-Nagy films, is listed with a 6-minute run time, but there are several excerpts and variations floating around. Here’s the original, I think:

The Times has a great account from 1952 of a screening of an “abstract art film” program organized by “Captain [Edward] Steichen” for the Museum of Modern Art’s “enterprising, energetic Junior Council,” which included both Lichtspiel and the early direct animation films of Len Lye.

But SFMoMA’s version is 5:17. The Minimalist Issue of Aspen Magazine, Nos. 5+6, published in 1967, includes a 1:40 excerpt on super-8 film. Fortunately for everyone without Aspen and/or an 8mm film projector, there’s Ubu.

Dali’s Pen Is

While scoping out the 1974 video art conference at MoMA, “Open Circuits, the Future of Television,” filmmaker Jose Montes Baquer decided that for some reason, Salvador Dali should be the artist he would collaborate with for his documentary. Baquer tells the story of gaining audience with Dali at the St Regis to pitch the project in an all-too-short interview with Christopher Jones for Tate, Etc. Magazine in 2007:

Then Dalí took a pen from his pocket. It was plastic and ivory coloured with a copper band at the centre. He said: “In this clean and aseptic country, I have been observing how the urinals in the luxury restrooms of this hotel have acquired an entire range of rust colours through the interaction of the uric acid on the precious metals that are astounding. For this reason, I have been regularly urinating on the brass band of this pen over the past weeks to obtain the magnificent structures that you will find with your cameras and lenses. By simply looking at the band with my own eyes, I can see Dalí on the moon, or Dalí sipping coffee on the Champs Élysées. Take this magical object, work with it, and when you have an interesting result, come see me. If the result is good, we will make a film together.”

The 2008 MoMA exhibit, “Dali and Film,” says this quote came from a letter from the artist. The resulting film, Impressions of Upper Mongolia, Hommage to Raymond Roussel, concerns the relationship between macro and microscopic, and was shown on Spanish TV in 1976. As interesting as it is, Baquer’s interview doesn’t exactly help make sense of what the film actually turned out to be. But the mentions of painting over film stills, and Vermeer, and the Dutch penchant for mapmaking as an art form, almost persuade me to put up with Dali’s pompous shenanigans to watch it.

Dali: The Great Collaborator [tate.org.uk]

Google Lens Cap View?

I was on the phone, trying to give directions to a friend to a small Japanese grocery store in Rockville, Maryland, so I pulled it up on Google Street View. Which turned out to be useless, but weirdly beautiful. Turns out all the Street View panos on that section of the busy road are out of focus, with mottled light patterns that look like the inside of a perforated coffee can.

Either last week’s earthquake has sucked Rockville Pike into a wormhole, or someone skipped the “1. Remove cover from panoramic camera stalk” step in his Street View Driver’s Manual.

Two Degrees Of Project Echo: Les Levine’s Slipcover

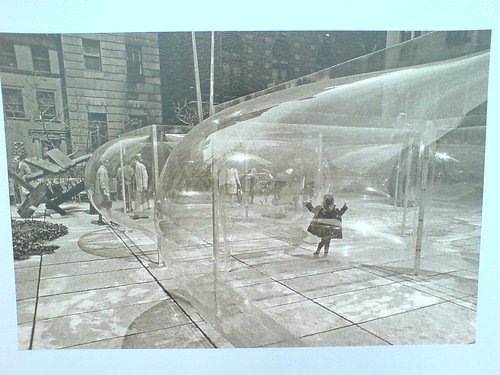

Holy smokes, people, just watch how these things turn out. In April, I spotted this photo at MoMA; it was in the second floor hallway just past the cafe, with no caption, and a date: 1970. I spent a few weeks trying to search up the name of the artist who made this remarkable, undulating acrylic structure in the Garden, to no avail [MoMA’s records didn’t have any more info about the photo.] I looked through the archive of shows, trying to match it, nothing.

Look at that thing, though, it’s like an ur-Dan Graham. an ur-Greg Lynn, for that matter. A more permanent Ant Farm inflatable. Suddenly, it occurred to me to ask John Perrault, who’s probably forgotten more than I’ll ever know about postwar art in New York. Sure enough, he nailed it: Les Levine. Star Garden, but 1967, not 1970.

Turns out 1967 was a great year for Levine–actually, looking through his works at the Center for Contemporary Canadian Art, a lot of years were great years for Levine. The Silver Environment (1961), vacuum-formed mirrored plastic? fabric? The perceptually disorienting acrylic bubble structures like Star Garden or Supercube Environment (1968)?

Disposables (1968) [above], a pop-minimalist grid of vacuum-molds of household objects, sold cheap and meant to be thrown away when their moment is over? Wow, Levine’s Restaurant (1968), New York’s only Canadian Restaurant, operated as a artist project, like Gordon Matta-Clark’s Food or Allan Ruppersburg’s Al’s Cafe, only earlier? Is that really TV test pattern print clothing there in 1978?

And then there’s Slipcover, a 1967 installation at the Architectural League [image via], which ran concurrently with Star Garden: three rooms covered in sheets of mirrored Mylar, where the space is constantly in flux because of the giant Mylar balloons inflating and deflating. The NY Times article shows Levine working on a balloon while one Linda Schjeldahl seals the edges of the Mylar wallcovering. Schjeldahl, Schjeldahl, where have I heard that name before?

Of course! The University of North Dakota’s archives of Gilmore Schjeldahl, founder of the Sheldahl Company!

The Company was the primary contractor for the Echo II Program. There are also files which contain information about the Echo I and II satellite balloons, as well as samples of Echo I and Echo II skins, and a file containing information about an art exhibition by artist Les Levine in 1967, at the Architectural League in New York City, which featured rooms made of Sheldahl’s Mylar laminates.

Billy Kluver, whose company Bell Labs operated the Project Echo satelloons, introduced Andy Warhol to Mylar and helped him make his 1966 Silver Clouds.

Meanwhile, the manufacturer of those satelloons supplied the same Mylar for Les Levine’s 1967 Slipcovers. Who had some help installing from his friend Linda Schjeldahl, the daughter-in-law of the company’s founder. A friend who, like her husband, Peter, was somewhat involved in the New York art world at that point.