“11. We claim the privilege of worshiping Almighty God according to the dictates of our own conscience and allow all men the same privilege, let them worship how, where, or what they may.”

– Joseph Smith, The Articles of Faith, “Thirteen statements describing the fundamental beliefs of members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.”

Author: greg

If You Can’t Say Anything Nice, Come Sit For Me

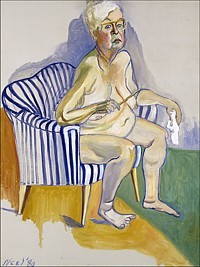

I watched the documentary Alice Neel last night, made in 2007 by the late artist’s grandson Andrew Neel. It’s pretty good, definitely worth a watch. Documentaries by family members come with a whole set of conflicts and challenges baked in, but Neel succeeds, I think, at identifying the craters and unexploded mines as he maps out the family’s emotional landscape.

I watched the documentary Alice Neel last night, made in 2007 by the late artist’s grandson Andrew Neel. It’s pretty good, definitely worth a watch. Documentaries by family members come with a whole set of conflicts and challenges baked in, but Neel succeeds, I think, at identifying the craters and unexploded mines as he maps out the family’s emotional landscape.

Neel’s story is intense–John Perreault, variously a critic, colleague, friend, and sprawling nude subject of the artist, thinks it’s long overdue for a Hollywood adaptation–and it’s hard to imagine that the definitive significance of the paintings left behind is somehow “worth” the suffering and abuse and privations endured by Neel’s kids (and grandkids). But then, that’s not a fair tradeoff. Neel’s rightwing son Richard is right to recognize that if it weren’t this set of problems, it would’ve been something else. Neel had to make her art; it was an obsession, really. And being able to make it, Perreault argues, made Neel a “better mother (and person) than if she had lived a horrid life of creative frustration. And took it out on her sons.”

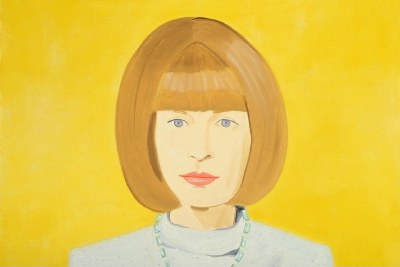

But that’s not the point. I mean, it is, but what I was wanting to post was the hilarious interview with Alex Katz, who Andrew effectively cast as “Figurative Painter #4,” When Katz finally manages to stop talking about his own work and how actually, he was doing whatever it was Neel was doing, only earlier, all he can say about Neel is that she was “an angry housewife.” You stay classy, Alex.

While Googling the quote, I found thanks to Time Out London, that Neel and Katz are having a portrait facedown at the moment. Though it’s hardly a fair fight. The Whitechapel Gallery’s having an Alice Neel retrospective, while Katz is showing new work at the National Portrait Gallery, including this lovely work, his portrait of Anna Wintour.

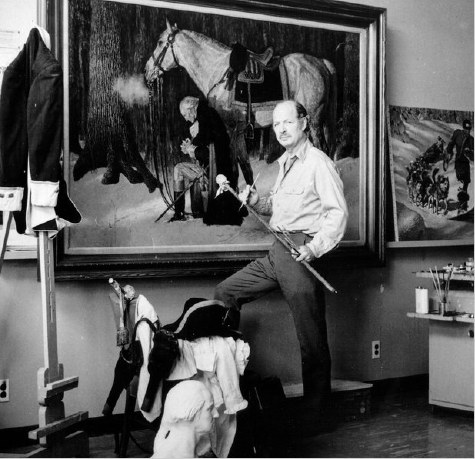

Paint Stick? Painting Crop?

Dear painting experts,

Please tell me that the brush-steadying stick with the sock on the end which is so vital to the painting process that it must be included in Serious & Important Photographic Portraits of such artists as Arnold Friberg and Winston Churchill has a venerable and esoteric name. And then please tell me what that name is. Thank you.

And awesome. Mahl stick. Here’s a lyrical history. Thanks, Jason!

images: Deseret News via NYT; life mag via acontinuouslean]

Related: Norman Rockwell, Triple Self-Portrait

On The Set With Grenada Invasion Re-Enactors

Awesome. The Ronald Reagan Presidential Library contains several elaborate sets where visiting elementary school students re-enact the invasion of Grenada. “[I]n keeping with Mr. Reagan’s first career as an actor,” the Wall Street Journal writes, presumably without irony, “the Reagan Library appears to have the most elaborate stage sets [of any presidential library.]” The sets include an Oval Office, the White House press room, and Air Force One:

The replicas are built to three-quarters the size of the originals, and decorated as they were in 1983. The mock Oval Office has pictures of Mr. Reagan and Nancy Reagan on their wedding day, replicas of Mr. Reagan’s favorite horse sculptures and jars of jelly beans.

Also:

Making a 27-year-old invasion relevant for today’s children isn’t always easy. Kids have to be told what communists are, and why Grenada becoming a communist country would have been a big deal.

The reenactments are part history lesson, part interactive game. The kids decide whether or not to invade, how to carry out an invasion, even how to deal with media leaks.

Apparently, the re-enactment only works with elementary and middle school students. Too many high school students reject the invade-or-negotiate-with-communist-dictators script, which was written by a 25-year-old screenwriter.

At Reagan’s Presidential Library, the Kids Are in Control [wsj via @demilit]

In The Medium Of Google

I know that what’s really needed around here is a redesign, and probably the addition of a few thousand tags. But right now that’s an 8th burner project, and I’ve only got a 4-burner stove.

But in the mean time, I’ve noticed–and perhaps you have too?–that many projects and ideas around here relate in some way to Google, and to the way Google shapes our perceptions and interactions with the art, architecture, information, people, and the world.

So I rolled it all up into one, big Google category. Besides my own projects, it ranges from this morning’s post on Michael Wolf’s photos; to the whole sculpture and roof facades on Google Maps thing; to my 2005 attempt to re-create Ed Ruscha’s Every Building on The Sunset Strip using the failed Street View predecessor, Amazon’s A9; and all the way back to my early 2002 experiments with Google AdWords poetry, and to my Jan.. 2002 request for permission to use the word “Google” as a verb in my first short film. Weird, interesting stuff.

greg.org/google/

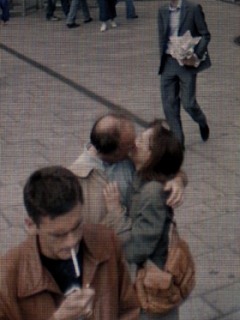

Michael Wolf, Street View Photographer

I’m glad and not surprised to see I’m the only person using Google Street View as an artistic source. Since at least last year, photographer Michael Wolf has been making a series of Street View-based works that explore urban life as it’s experienced, seen, and transmitted.

Wolf roams Google Street View in classic street photographer tradition, searching for the hidden, the unexpected, the sublime, the beautiful, the overlooked, images which reveal something about the character of a city and its residents. So far, he’s done Street View Manhattan and Street View Paris.

According to his Amsterdam dealer, Galerie Wouter van Leeuwen, where he showed this Spring, Wolf has spent over 400 hours searching Street View, which sounds like a direct translation of street technique to the virtual world. His careful cropping and composition, too, resonate with street photography’s quest for stolen, fleeting, magic images.

Some of his images carry Street View’s trademark aesthetics: blurred out faces [but not as many as I’d expect], navigation overlays and cursors, and occasionally the fractures and distortions of the pano image knitting algorithms. From the prominence of the screen pixels, it looks like he actually reshoots images on his screen, or as one press release put it, “pictures of pictures.”

His series Street View A Series of Unfortunate Events looks like archetypal on-the-scene photojournalism, only stripped by any news or context other than place. Though Wolf himself eliminates any place specifics or links, leaving each image to stand on its own.

In March, the photography museum FOAM and the Virtueel Museum Zuidas staged an exhibition of Wolf’s Paris Street View photos on the street. Giant prints were placed around Gustav Mahlerplein, a plaza in a modern culture and office complex on the ring road south of Amsterdam. Unfortunately, no images of the exhibition have made their way back into Google Maps.

While Wolf’s quote of Robert Doisneau’s Hotel de Ville kiss is the most obvious, my favorite throwback images are like the ones here, where he finds in Google layers of reflections and perspectives that’d do Lee Friedlander and Harry Callahan proud. Really beautiful stuff.

Michael Wolf photography [photographymichaelwolf via things magazine]

Casting Long Shadows

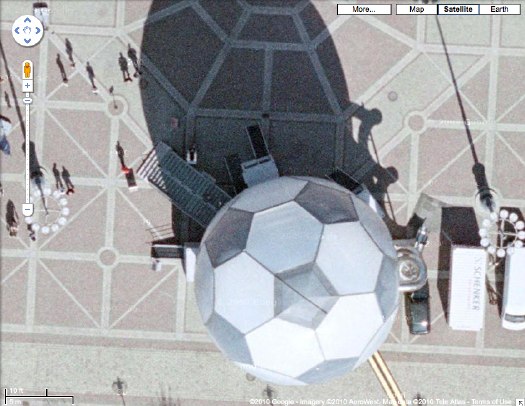

This has been sitting on my desktop since last month, when Google Maps announced the addition of 45-degree Aerial View imagery for new locations, including Dortmund, Germany.

So I clicked over to Dortmund, and zoomed in there to the central platz [Friedensplatz, actually], just getting more and more psyched to see that sweet-looking geodesic soccer ball pavilion up close, and then poof, at the last minute, the final zoom, the Aerial View showed up, and it was from much later. The soccer ball was gone.

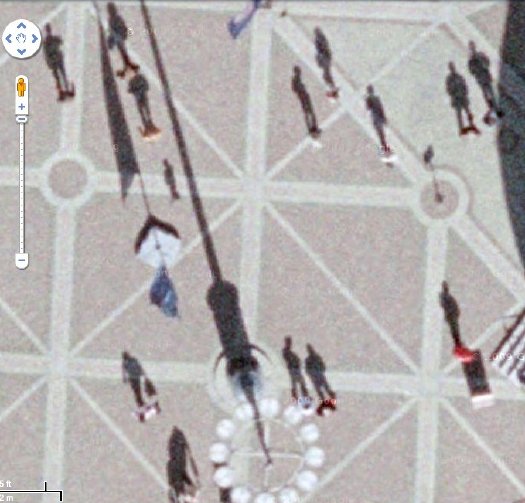

But then I forgot all about Google’s 45-degree View when I saw the sun doing it for me. These attenuated morning shadows are just awesome. Like 19th century silhouette portraits as reimagined by Giacometti–and shot from outer space.

Which reminds me of the statue of a horse and rider in front of the Noordeinde Paleis in The Hague, the first building I saw on Google Maps which had been obscured by the Netherlands’ unique polygonal camo pattern:

[An update on those Dutch Camo Landscape paintings I was talking about making: I’m still going to do it. One thing I’m very glad for is taking all the screenshots I need for the images I want. I first noticed the changes last winter, but now every the camo on site I’ve mentioned on greg.org has been replaced with typical square-pixel obscuring. Functionally, the camo still works, but aesthetically, it’s a real loss.]

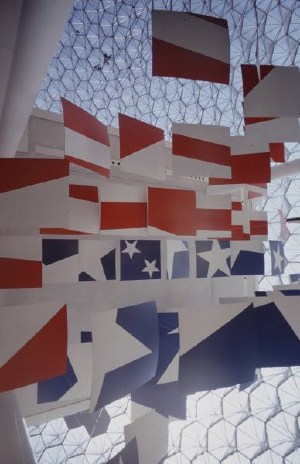

Now about that ball: It is probably better known to the millions of soccer fans in Germany as the WM-Globus. It was conceived in 2003 by artist/musician/actor André Heller, who ran the cultural and arts program for the Deutscher Fußball Cultural Foundation. Described by Heller as a “consulate of anticipation,” the Globus was sent on a 1000-day, 12-city tour in advance of Germany’s hosting of the 2006 World Cup. It’s 18 meters high, weighs 50 tons. Two interior floors contained football memorabilia and multimedia installations, while the pressurized scrim exterior contained an LED map and nightly light shows. Lighting effects designer Anthony Quodt has several articles on the making of the WM Globus and its specs on his site, lightlife.de. Too bad it predates the YouTube era, because the stills look like a hot, glowing mess.

After the World Cup, a Hamburg entrepreneur named Dr. Alexander Extra purchased the Globe from the DFB for EUR300,000, with plans to transform it into a permanent museum of sports culture, the Sporteum. Alas, no money was forthcoming, and the Sporteum failed to materialize. So Dr. Extra put the Globus on eBay last summer. Which turns out to have been a bad time for the geodesic soccer ball-shaped pavilion market, because bidding stopped reached just EUR50,000. The unidentified buyer was reportedly also from Hamburg, so I expect it’s still sitting in the warehouse, but I’ll look into it.

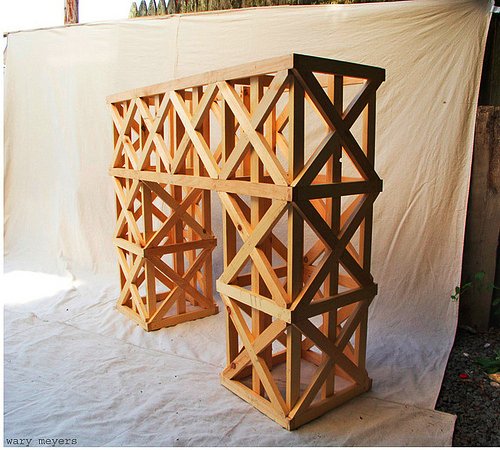

Wary Mari

And thus we see the painful difference between meaning to buy Wary Meyers’ awesome-looking design project book Tossed and Found and actually buying it. I would have been inspired by their Enzo Mari autoprogettazione-esque mantle many months ago. What progettazione have I not thought of in that time? I’ll never know.

Progettazione 1×2 [warymeyers]

Voice Of The Taxpayer (1990) By John Czupryniak

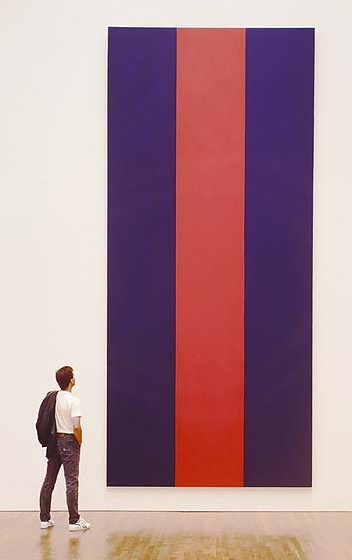

When it was publicly announced in March 1990 that the National Gallery of Canada had purchased Barnett Newman’s 1967 painting, Voice of Fire for $1.8 million (Canadian), there was an immediate press and political uproar that so much public money would be spent on what seemed like so little. A conservative MP, who was also a pig farmer, challenged that anyone with “a couple of cans of paint, a roller, and ten minutes” could make Newman’s 18-ft tall bands of red and blue.

When it was publicly announced in March 1990 that the National Gallery of Canada had purchased Barnett Newman’s 1967 painting, Voice of Fire for $1.8 million (Canadian), there was an immediate press and political uproar that so much public money would be spent on what seemed like so little. A conservative MP, who was also a pig farmer, challenged that anyone with “a couple of cans of paint, a roller, and ten minutes” could make Newman’s 18-ft tall bands of red and blue.

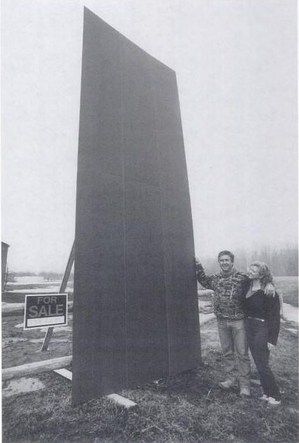

Greenhouse owner and house painter John Czupryniak’s wife Joan, upon seeing the news reports, told him, “Hey, anyone could paint this, even a painter.” And so he did.

Mr. Czupryniak studied reproductions of Voice of Fire and because he was unfamiliar with canvas painting techniques, he built up a 16×8 panel of plywood, and made a full-scale replica of Newman’s work. He struggled with the title before arriving at Voice of the Taxpayer.

Then he offered it for sale. The government price was $1.8 million. For you, though, or any Pierre off the street, it was just $400, the cost of time and materials. Almost immediately, Voice of the Taxpayer became part of the art controversy. The picture of the Czupryniaks posing with the [for sale] painting was published in The Ottawa Citizen.

In the art world’s critical self-examination of the Voice of Fire controversy, noted art historian Thierry du Duve published an essay, “Vox Ignis, Vox Populi,” in the Montreal art journal Parachute which focused on Mr. Czupryniak’s response. It is awesome:

Like many avant-garde painters, Czupryniak paints against. A transgressive gesture along the lines of Dadaism, Voice of the Taxpayer assumes its full significance only in diametrical opposition to the tradition it attacks. A postmodern parody of modernism’s celebrated flatness, Voice of the Taxpayer is a quote, a pastich that appropriates the work of another, empties it of its meaning, and presents itself as a critique of ‘the originality of the avant-garde and other modernist myths.’ Better still, in its abstract guise Voice of the Taxpayer is a real allegory of the art world as institution, neither more nor less than Courbet’s L’Atelier du peintre. Is it a bad painting? No it is bad painting, if you get the difference.

It is actually a subtle and refined conceptual piece whose feigned innocence makes the emperor’s new clothes visible to all. The “indispensable vulgarity’ (Duchamp) of its title provokes the return of the repressed of the sole ‘convention’ that modernism forgot to deconstruct, the money of the people on whose back the elite builds its culture. In short, Czupryniak has got it all: he is more provocative than Rodchenko, more sarcastic than Manzoni, more strategic than Buren, more political than Haacke, more nationalist than Broodthaers, more demagogical than Koons, more neo-geo than Taaffe, all this with Duchamp’s caustic humour, and sincere to boot!

It is an epic of art criticism. Or maybe Parachute was punked by the theorist’s smartalecky brother, Jerry du Duve, I can’t quite tell. Whichever du Duve, he, too, expressed his doubts:

The critical interpretation of his Voice of the Taxpayer which I gave above is perfectly plausible, and that’s what worries me. A perverse and cynical art historian, I would have appropriated Czupryniak just as he appropriated Voice fo Fire. I would have taken a painter and made him into an artist, an ‘artist in general.” But I am not interested in defining an artist in this way.

Oh wait, never mind! Du Duve suddenly flips [“I only played at being cynical to show you how absurd it is.”] and makes an argument for Voice of the Taxpayer based not in cynicism, but in sincerity. Czupryniak “emulated Newman by simulating him just as Newman had emulated Mondrian by painting against him.” In fact, Voice of the Taxpayer embodies what du Duve calls “the fundamental ethical meaning of the ‘reductive’ aesthetic governing Voice of Fire, as well as all great modern painting” [italics in the original, bold added because, holy smokes!]: painting that demonstrates its true universality precisely because “anyone can paint this, even a painter.”

Du Duve then considers at great length how Mr. Czupryniak’s pricing scheme deftly maps out the incongruities between artist and painter, value and worth, elites and the public, boss and laborer, exploiter and exploited. Every dollar between $401 and $1.8 million, he writes, accrues to Newman’s status as an artist as perceived by the cultural elites–and as extracted by them for their own aesthetic pleasure from the unappreciative public [the Taxpayers] who got stuck with the tab.

Du Duve then considers at great length how Mr. Czupryniak’s pricing scheme deftly maps out the incongruities between artist and painter, value and worth, elites and the public, boss and laborer, exploiter and exploited. Every dollar between $401 and $1.8 million, he writes, accrues to Newman’s status as an artist as perceived by the cultural elites–and as extracted by them for their own aesthetic pleasure from the unappreciative public [the Taxpayers] who got stuck with the tab.

I’m surprised du Duve doesn’t mention it, because I can’t stop marveling at how Mr. Czupryniak’s project maps so closely with Newman’s and the creation of Voice of Fire.

Newman, a celebrated artist was invited by his government, to make a work almost to spec, for which he received $423.60 to cover the cost of materials. But not his labor. Instead, his contract with the USIA guaranteed him full control over the painting’s “equity,” which his wife went on to monetize rather successfully. I guess we should add Voice of the Shareholder to the chorus.

What is the fate of Mr. Czupryniak’s historically important masterpiece? Did he sell it? Did he keep it? Does it still exist, perhaps turned into a red and blue storage cabinet in the nursery? In 20 years, no one seems to have asked, so I have put in a call to find out. Stay tuned.

Thierry du Duve’s “Vox Ignis, Vox Populi” was reprinted in the 1996 anthology, Voices of Fire: art, rage, power, and the state. Buy it from Amazon, or try to read the essay in Google Books’ preview mode.

[image right of Ivan Chermayeff’s Newmanesque flag panels in Buckminster Fuller’s US Pavilion at Expo67: Mark Kauffmann for LIFE]

Flame Canada

Speaking of National Gallery of Canada upheavals, Walrus Magazine, late-career post-minimalist kitsch, and Blake Gopnik:

Speaking of National Gallery of Canada upheavals, Walrus Magazine, late-career post-minimalist kitsch, and Blake Gopnik:

In March 2010, Walrus celebrated the 20th anniversary of longtime NGC contemporary curator Brydon Smith’s purchase of Barnett Newman’s towering 1967 painting, Voice of Fire for $1.8 million, which was apparently a lot of money, even in Canadian. The announcement [of the price] set off a political firestorm of conservative, populist wrangling and hearings. It was Canada’s own homegrown version of the American Right’s culture war on the NEA, the NGC’s most famous controversy.

Well, famous in Canada, anyway. As Greg Buium noted in his article, “Firestorm”:

Internationally, the affair caused barely a ripple. Art in America published a short news story. Blake Gopnik, chief art critic at the Washington Post, was then a doctoral student at Oxford and only heard about it from his family back home in Montreal.

And here I am agreeing with Gopnik again! Awkward! Newman painted Voice of Fire for “American Painting Now,” Alan Solomon’s exhibition in the Buckminster Fuller dome at Expo 67. Which I wrote about and dug into rather deeply last October. I even quoted from Voices of fire: art, rage, power and the state, a 1996 anthology of the controversy, and yet I’d forgotten it until reading Buium’s piece. [Maybe it’s just me.]

According to Smith’s account of the making of, Newman’s painting, 8×18′ high instead of 8×18′ wide, Voice of Fire was designed to Solomon’s request for “very large,” vertically oriented paintings able to “hold their own” in a “soaring airy structure” and amidst a lot of visual “competition,” and which, because of the steady movement of crowds through the pavilion, “visitors would not be able to spend long periods looking at.”

Smith also wrote about having spontaneous discussions with Annalee Newman about her husband’s “concern at that time about the undeclared war in Vietnam,” a concern which hovered over the entire pavilion project. Co-editor John O’Brian quoted Solomon as saying, “Given world conditions at the moment, [the plan is] to soft sell America rather than show our muscle.”

Yeah, capitalism, but I’ve always thought Voice of Fire was the best painting of Newman’s weakest period, the hard-edge acrylics, which filled the last big gallery of Ann Temkin’s Philadelphia Museum retrospective. [Hold on, I’m trying to forget that triangle-shaped canvas all over again.]

A late-period acrylic, made to order by an ambivalent artist for a drive-by spectacle designed to distract from the war. With stripped-down, hard-edge abstraction that provides the perfect symbol for anti-intellectualist critics of the art world’s shenanigans. It all sounds like a prime candidate for Blake Gopnik’s Kitsch You Didn’t Think Of! list.

And yet he left it off. With such political savvy I predict a bright future in Canadian art politics for Dr. Gopnik.

O Brother Where Art Thou?

It takes a big man to acknowledge when he agrees with Blake Gopnik.

Paddy Johnson’s post about controversy at the National Gallery of Canada led me to “Pop Life: Art in the Material World,” Jack Bankowsky et al’s solipsistic exhibition at Tate Modern.

“Pop Life” used Warhol’s collapsing of fine art and commerce and his cultivation of an artistic persona as a hook for showing whatever by a bunch of usual market suspects, celebrants of the conflation of art and consumptionist life: Hirst, Murakami, Koons, Kippenberger, Prince, it brings on a three-years-ago haze even typing them. Anyway, what joy, this trophy show opened in Ottawa this summer.

Sold Out? The legacy of Pop Art: Is it avant-garde or is it kitsch?

And I’ll be damned if Blake Gopnik didn’t steal the show and win the “debate” co-sponsored by the NGC and Walrus Magazine. Not that the question, “Sold Out? The legacy of Pop Art: Is it avant-garde or kitsch?” [“Yes, yes and yes, so?”] was any more enlightening in 2010 than it was in 1962 when the Met asked it. Or that Gopnik’s sparring partner arts editor Robert Enright ever stood a chance against Gopnik’s Washington-honed, knee-jerk counterintuitiveness. Maybe if there’d been any kind of level-setting at the get-go about what kitsch was, and why it was good, bad, good-bad, or bad-good–but no, this whole thing was DOA.

Gopnik began with a counterintuitive [!] ploy, declaring late works by non-Pop artists–Bourgeois’ spider, Serra’s torqued ellipse, Christo’s Gates–to be the kitsch, manufacturers of the popular, comfortable “Art” experience, and the Koons, Hirst and Murakami to be the expectations-confounding avant-garde.

Which is interesting as far as it goes, but he didn’t really take it anywhere. Instead, Gopnik went on to argue with breathtaking cynicism that it’s not Hirst’s diamond skull, but his auction; not Warhol’s paintings, but his entourage; not Koons’s vanilla porn photos, but his career that are the real Art. It’s not the playa, and not even the ball, but the game itself.

It’s an incredible position for a critic to argue, that Avant-garde Art is not just a luxury good, but a luxury lifestyle! But if a life spent selling eight-figure sculptures to a handful of billionaires while simultaneously marketing any number of bridge collections to the lesser Basel masses is the pinnacle of artistic achievement, then why isn’t Koons’, Murakami’s, and Prince’s dealer Larry Gagosian in the show? Or Bankowsky’s husband Matthew Marks?

After the wrap-up, the post-debate handshake, the houselights coming up, Gopnik actually went back to his mic and invoked the name of his brother who, with the late Kirk Varnedoe, had actually curated a major exhibition exploring Pop’s disruption of cultural boundaries, “Hi-Lo” at MoMA: “If anyone here came thinking they were seeing Adam Gopnik and Michael Enright tonight, you can get your money back at the front door.”

Sold Out? [walrusmagazine.com]

Art Is Where You See It

Dealer-turned-public art empresaria Emi Fontana talking in Artforum about West of Rome:

…people believe that public art needs to occupy planned and assigned spaces. What we’re doing is much more fine-tuned: You have to find the space that resonates with the work and with the artist’s practice in general. This is fascinating to me. It’s something you can do well in a city you love, and I really love Los Angeles. I came here for romance, but when the romance was over I realized I still had a huge romance with the city. It is a constant source of inspiration for me.

Baby Ikki bugs, but Emi rocks. But I always thought that West of Rome was selling in some way, too, not just putting on shows outside the gallery/museum/institutional/white box paradigm.

Aha, West of Rome converted to a non-profit and became West of Rome Public Art in 2009.

Also, 500 Words is really such a consistently interesting feature. So seemingly simple, yet so rich. It’s the chocolate mousse of Artforum.com.

500 Words | Emi Fontana [artforum.com]

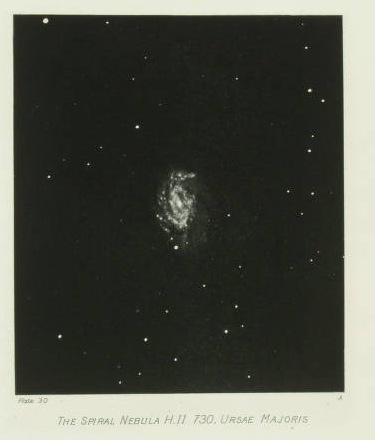

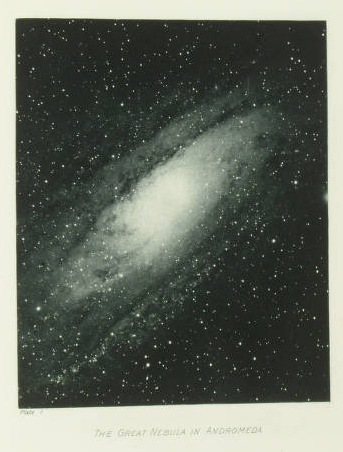

How To Make Lantern Slides Of Spiral Nebulae

While wandering through the National Air and Space Museum [family’s in town], I stumbled across James Keeler’s lantern slides of spiral nebulae, taken at the Lick Observatory outside San Jose beginning in 1888.

Keeler was a pioneering astronomer at what was the largest reflector telescope at the first permanent mountaintop observatory in the world. He wasn’t the first astrophotographer [moon photos don’t count; everyone from Daguerre forward shot the moon], but he was a great one, and his deep sky photo survey is one of the earliest and most ambitious I’ve found. Keeler photographed hundreds of spiral nebulae and boldly estimated that at the rate he was finding them, there were at least 100,000 of them out there.

Three of his slides are on display at the museum. In the midst of what it called the “photographic fad” of 1890, The New York Times covered a lantern slide presentation Keeler made in December of that year at the New York Camera Club on Fifth Avenue. [Alfred Stieglitz joined the Camera Club soon after in 1891.]

Keeler’s slides, which he acknowledged were executed by a staff member at the observatory, were nevertheless described as “excellent in their make” and “some of the best specimens of star photography.” He went into great depth on the technical challenges of making telescopic photographs of the stars:

The usual method of keeping the star on the plate in photographing was by moving the telescope, but owing to the size of the instrument at the Lick Observatory this was impossible, as the telescope weighed seven tons. The plan adopted, therefore was to make the plate movable by means of turning screws.

…

…it happens that a different focus is obtained in the big telescope. The dry plate is therefore placed in the tube nine feet from the eye piece, a hole having been cut in it for that purpose…When the plate is developed the operator has to go it in a blind sort of fashion, as the smaller star images will not appear till the developing work is done.

…

Photographing stars, especially the small ones, is tedious work, as in some cases teh exposure must last for several hours. During all that time the plate or telescope must be moved so that the image of the star will continue in one place.

Keeler was the director at Lisk when he died suddenly in 1900, and his colleagues undertook to publish his sky survey and photos.

Photographs of NEBULAE AND CLUSTERS. Made with the Crossley Reflector was published in 1908 by the University of California. It contains 70 full page, hand-printed heliogravures [which is French for photogravures, which is actually French for any kind of photo-based printing technique, not just the copper plate-based intaglio-style prints associated with photogravure in English].

The Clark Art Institute has helpfully digitized all 70 of Keeler’s posthumously published plates. So far, I have not found information on the extent or state of his negatives, slides, or other prints. I imagine I’ll be digging into the Lisk and UC archives soon.

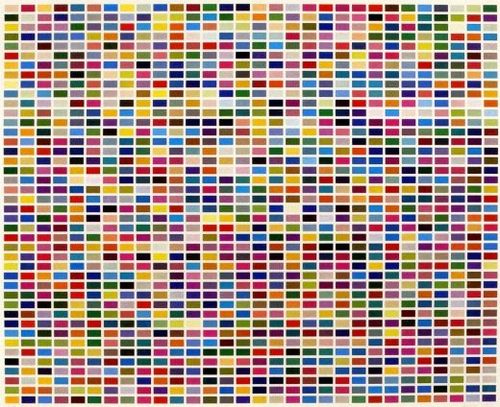

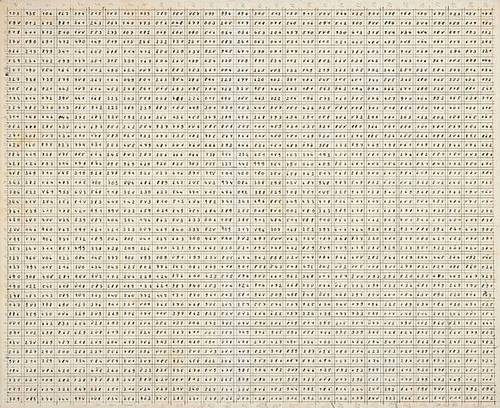

How To Make A Gerhard Richter Color Chart Painting

Well, a color chart print, anyway.

In 1974, at the height [and end] of Gerhard Richter’s production of painted grids of colored squares and rectangles, he also published Colour Fields. 6 Arrangements of 1260 Colours, a portfolio of six prints [the auction house Lempertz said silkscreen, but the artist’s own website says offset] on white board. There was an edition of 32, plus a few proofs and extras.

One of those loosies [top, looks like it was an arrangement b] was later signed and given to Carl Vogel, the head of the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts, along with, hello, Richter’s sketch for the piece, which contains numbers corresponding to the various colors.

It’s practically a Richter paint-by-numbers kit! I’m sure whoever bought the set in June from the auction of the late Prof. Vogel’s collection has already started coloring it in, even though paint was apparently not included in the sale.

Lot 1169, June 2010: Gerhard Richter, Untitled (Colour fields 1260 colours in 6 arrangement), sold for EUR57,000 [lempertz-online.de]

Colour Fields. 6 Arrangements of 1260 Colours, 1974 [gerhard-richter.com]

Previously: How To Make A Gerhard Richter (Squeegee) Painting

John Cage’s One11: The Making Of, Now In English

A couple of weeks ago, I watched Henning Lohner’s film essay/documentary about working with John Cage to make One11 and 103, Cage’s only feature film project, completed just before he passed away in 1992.

It’s on YouTube, chopped up in several parts, and mostly in German [One11 and 103 was made for German TV], but now Ubu has posted the English version, so you non-Germans can actually figure out what’s going on. [ One11 and 103 is online, too, though it has the 3sat logo burned into the upper corner, which turns the whole thing into a 90-minute promotional bumper for the station.]

For One11, Cage and his collaborator Andrew Culver used a computer program to generate a series of chance operations, instructions for light placement and movement within an empty soundstage; for camera movement and positioning; shot length; and for editing.

Narrative- and nearly content-free, the 17-segment film was accompanied by 103, a 17-segment orchestral composition that was also based on chance operations. The film’s title follows Cage’s numbering system: the eleventh composition for one performer, in this case, the camera man. So while Cage explains the film as being “about the effect of light in a room,” it’s also very much about the perception, movement, and recording of the cinematographer, Van Carlson.

Cage made the point to Lohner early on that his idea wouldn’t “waste” any film. And sure enough, it turns out the final shooting ratio was an astonishing 1.4:1, with less than 600 meters of extra footage–which, we are told, was used in the opening and closing credits. It’s almost like Cage went to film school during the Depression.

The obvious appeal of an abstract light show aside, watching all this self-conscious randomness [I’ve been going through and replacing “random” with “chance,” since that’s the specific term Cage uses. I think there’s a meaningful difference.] really puts the conscious decisions of location and content into high relief. It also makes me want to remake One11 in another environment and see what happens. I’d also wonder how many more decisions could be randomized, and to what effect? Eventually, if you put a decision factor into play, the randomness of it will generate a distinctive effect, if not an actual style. It’s one of the conundrums of Cage’s work that I like picking through.

One11 and 103: the making of [ubu.com]

You know, at $27, it wouldn’t kill you to buy Mode Records’ DVD version of John Cage: One11 with 103, either, from The Complete John Cage [amazon]

NOW THAT I THINK ABOUT IT UPDATE: You know, posting this really seems like a departure for Ubu. I mean, Ubu began posting vintage, impossible-to-buy-or-even-find works, but with One11 and 103, they basically ripped a commercial DVD published in 2006 by a small, well-known, high-quality independent publisher of modern music. Am I missing something here?

UPDATE UPDATE: Yeah, Ubu’s versions of both One11 and Making of One11 first appeared on The Sound of Eye, an equally amazing art film and experimental music blog, albeit one with a different approach to posting works that are readily available in the commercial market. Ubu announced a collaboration with Sound of Eye a little while ago.